This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Unmasking the IQ Lie

by Janet Selcer, Susan Conrad, Stu Flaschman, Al Weinrub, Susan Orbach, Joe Schwartz, & Mike Schwartz

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 2, March 1974, p. 9 – 25

Jensen, Herrnstein and others have claimed that people’s IQ is highly inherited and plays a large part in determining their “success” in later life. Their arguments can be broken down into the following points, none of which has any ground to stand on, as we shall demonstrate in the following articles:

- IQ tests objectively measure something called “intelligence”, which differs from person to person.

- The ability to perform well on IQ tests is inherited.

- Intelligence (defined and measured by IQ) is what determines people’s socio-economic status in life.

From these points Jensen goes on to claim that the 15 point difference in the average IQ test scores between blacks and whites reveals a genetic inferiority of blacks, which he says makes compensatory education and other social programs doomed to failure. Herrnstein goes further to say that some people are born to be unemployed or poor since they are genetically inferior. Jensen, Herrnstein, and the others who push the IQ line find the source of society’s social inequity in the genes of its victims.

In this section of the magazine we show the fallacies of all these arguments. “IQ and Class Structure” demonstrates that IQ is not a cause of success and that it is irrelevant to understanding the U.S. class structure. Next we explain what the IQ test really measures, and finally in the articles entitled, “Heritability: A Scientific Snow-Job” and “The Case for Zero Heritability” we show there is absolutely no basis for claiming that IQ is inherited.

So much for the claims of Jensenism.

IQ AND CLASS STRUCTURE

This article is based in part on an article by Herbert Gintis and Samuel Bowles, “IQ in the U.S. Class Structure,” which originally appeared in Social Policy, vol. 3, nos. 4 and 5, Nov./Dec., 1972 and Jan./Feb., 1973.

The ideologues of IQ have been rightly attacked on the basis that their “scientific” claims are no more than distortions and lies. But those who attack Jensen, Herrnstein, and Shockley on this level often share with them an important underlying assumption. The assumption is that IQ is basically important to being an economic success in American society. Put another way, if you’re smart, you’ll succeed. Those who fail to analyze and attack this assumption are ignoring the essential political content of the entire IQ controversy.

In fact, IQ is not an important cause of economic success. Arguments about the heritability of IQ or what IQ measures are really irrelevant to understanding why some people are wealthy and successful and others are not. What are the causes of economic success, if not intelligence? And what part does IQ actually play?

During recent years many opponents of Jensenism have not addressed these crucial questions. They have rather ineffectively argued that IQ is affected by environment, and is therefore changeable. The answer, they say, is in progressive social reform—in providing equal opportunity by improving “disadvantaged environments.” By sticking to an IQ-is-important-to-success basis, though, these reforms have had severe shortcomings. First, even though some programs have raised IQ scores, they have not increased the economic gains of their participants. There is continued militancy. Program planners then become disillusioned and end up putting the blame on the victims. Second, many “improved environments” for raising black IQ’s are simply modeled after those of whites. This orientation seems to accept the idea that intelligence differences among whites of different class and environmental background are “natural.” The meaning of IQ and the class structure of white society go unchallenged. And third, many of these program planners accept the idea that society rewards people who are talented and smart by giving them better jobs, higher pay, etc. The corollary to this notion is that programs to eliminate unfair and unnecessary causes of lower IQ’s will eventually lead to a stratified society based on intelligence alone. In fact, it would be even more absolutely stratified than now, but fairly so—since the “dumb” would be poor and the “smart” would be rich! As long as people think that IQ and intelligence are basic to success, and refuse to look at the source of the blatant inequities in the U.S. class structure, they will end up reinforcing these inequities every time.

Why have so few people questioned this basic, limiting assumption while practically every other part of the Jensen school has been blasted? The answer is that IQ serves an important function in maintaining the status quo for those who benefit from it by making it appear right and legitimate. IQ serves to detract from the real issues. Having a high or low IQ does not determine whether a person will be rich or poor; but it has made the privileged positions of the few appear more fair and acceptable.

IQ Doesn’t Determine Success—The Evidence

The evidence presented in the following tables demonstrates that IQ is unimportant in determining who makes it and who doesn’t. The data shows that IQ score and economic success do correspond; but there is also a direct relationship between years of schooling and economic success and between social class and economic success—more strongly than IQ. There is no logical reason for Jensenists to point to high IQ as the determiner of success. Why not schooling or social background? When each factor is considered separately to find out what has the most influence on becoming economically successful, we fmd that the influence of IQ is neglegible. It only appears to affect economic outcome because it is attached to more important influences—schooling and social class. The following tables will demonstrate this clearly.

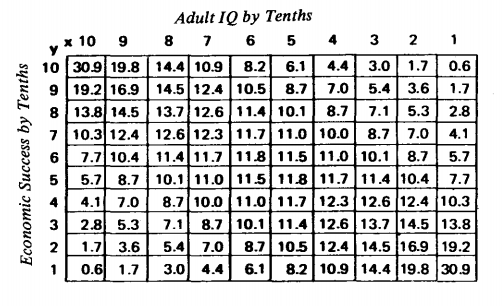

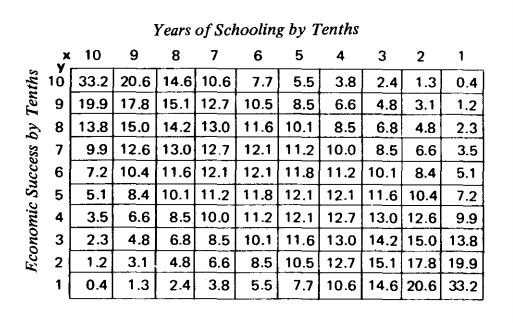

Table 1* Probability of Attainment of Different Levels of Economic Success for Individuals of Differing Levels of Adult I.Q.

Table 1 shows the connection between adult IQ and economic success (the relation most often referred to by Herrnstein). Across the top, the table is divided in terms of IQ—from the lowest 10th of the population (1) to the top 10th (10). The same is done with economic success starting from the lowest 10th of the population up to the highest. The numbers in the slots correspond to how a sample population falls into these categories when their IQ’s and economic success are measured and related to each other.1

In a survey of 100 people in the top 10th of the population for IQ, a person in that category would have a chance of being also in the top 10th economically approximately 30.9% of the time. This person’s chance of being in the 2nd highest 10th of the population for economic success is 19.2%, in the 3rd highest, 13.8%, and so on. His or her chance of being at the very bottom while still being in the group of 100 with such a high measured IQ is only about 6%.2

Since the chances are randomly 10% that any individual will end up in any particular 10th of the population, we could also say that the person in the top 10th IQ rank is 3.09 times (about 3 times) as likely (10% x 30.9) to end up at the top economically and .06 times as likely (10% x .6) to be at the bottom, than if IQ and economic success had nothing to do with each other. This is just another way of describing how much these two factors—economic success and IQ—will occur together in people.

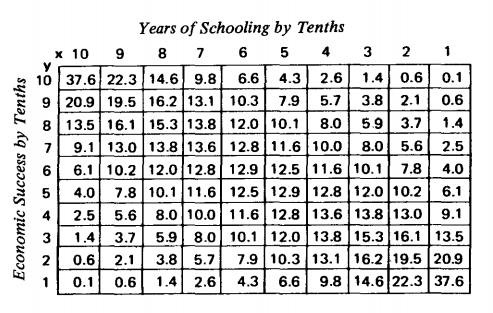

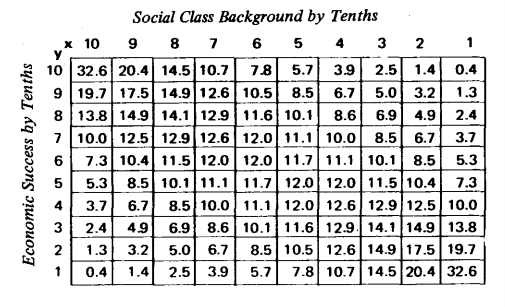

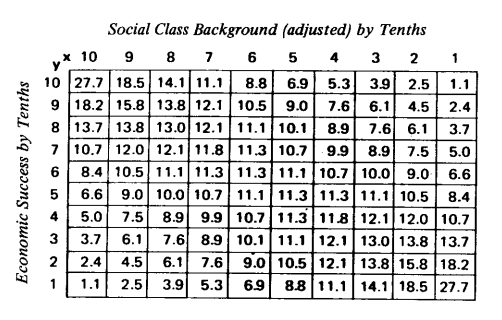

So Table 1 illustrates the most immediate support for the IQ theory of social stratification—that high IQ and high level of economic success do have a strong association. On the other hand, Tables 2 & 3 show how misleading and narrow this statistical support really is. For when years of schooling (Table 2) and social class background (Table 3) are related to economic success, even stronger associations occur. For example, an individual in the top 10th in schooling is 3.76 times as likely to be also at the top economically and .01 times as likely to be at the bottom, while the corresponding numbers are 3.26 and .04 for social class background. These statistics could easily be used to draw up a “level of educational attainment theory” or a “socio-economic backround theory” of social stratification since they are stronger than the correlation Herrnstein and the others use. Clearly, though, this is a case of selectively using numbers to prove one’s own theory—which is just what they can do by using only the information found in Table 1 in his arguments. There are logical errors in using any of this data by itself to draw conclusions.

Table 2* Probability of Attainment of Different Levels of Economic Success for Individuals of Differing Levels of Education

Table 3* Probability of Attainment of Different Levels of Economic Success for Individuals of Differing Levels of Social Class Background

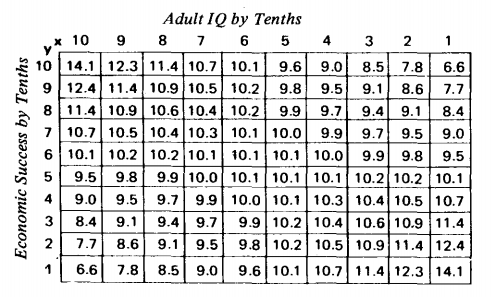

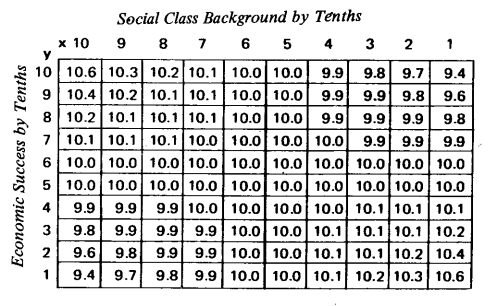

Tables 4-7 show how these factors (IQ, years of schooling, and social class background) contribute independently to a person’s economic status, and to what degree. This is done by combining certain of the factors while holding one of them constant. For example, according to Jensen’s claims, individuals who have the same social class background, but differing levels of adult IQ should fare quite differently in terms of economic success, depending on the amount of difference between their IQ’s—the one with a higher IQ coming out better. Jensen would say that years of school and social class background only relate to success (Tables 2 & 3) because they are associated with higher adult cognitive (lQ) skills (i.e., people with more years of schooling and higher class background are also richer because they are smart to begin with). Table 4 shows that this is false. For in Table 4 individuals of equal education and class but differing adult IQ’s do not vary too much at all in economic success; certainly much less than Table 1 would indicate they do (14.1% chance for the top in Table 4 as compared with 30.9% in Table 1). This indicates that the high relationship exhibited in Table 1 must be more due to the association IQ has with schooling and class than it does when measured as the primary cause, as in Table 4 (where its importance goes down). So although higher IQ’s and economic success tend to go together, IQ’s are not an important cause for this.

Table 4* Differential Probabilities of Attaining Economic Success for Individuals of Equal Levels of Education and Social Class Background, but Differing Levels of Adult I.Q.

Table 5 deals with the role of schooling in promoting economic success when viewed independent of IQ. The IQ proponant argues that the reason schooling and economic success are strongly associated in Table 2 is due to the fact that success depends on intellectual capacities (as measured by IQ). Yet Tables 2 & 5 are almost the same. When adults with equal IQs get a high level of schooling, they achieve only about the same level of economic success. as do adults with a high level of schooling and differing IQs (33.2% is highest in Table 5; 37.6% in Table 2—a negligible difference). Put another way, Table 5 shows that years of schooling does indeed make a difference on an individual’s economic success, but that the intelligence factor that IQ may measure, accounts for an insignificant part of that schooling’s influence. What you get rewarded for because you went to school x number of years isn’t due to IQ. It may be due to what you learned there, or to the diploma you got, or to the particular socialization that went on. It must be some combination of these factors that school generates and rewards, and upon which it selects individuals for higher education, rather than IQ, that makes years of schooling significant.

Table 5* Differential Probabilities of Attaining Economic Success for Individuals of Equal Adult I.Q. but Differing Levels of Education

Table 3 has already shown the strong association between class backround and success. Table 6 shows that even if everyone had the same opportunity in terms of equal IQ, their social class would still serve as a good prediction of whether or not they would succeed economically. For example, suppose two individuals have the same childhood IQ, but one is in the 2nd highest lOth in social background, while the other is in the 2nd lowest 10th. Then the first is 7.4 (18.5/2.5) times as likely as the second to attain the top 10th in economic success.

Table 6* Differential Probabilities of Attaining Economic Success for Individuals of Equal Early I.Q. but Differing Levels of Social Class Background

We’ve seen in Tables 4-6 that the effects that IQ seems to have on economic success is really via its connection to years of schooling and social class. It is unimportant as a factor in itself. But let’s go back to a table like Table 1 (a measure of the relationship between IQ & economic success)—but this time corrected in light of our new information—to see for sure. Suppose we now measure the effects of IQ on economic success, so that years of schooling and class background don’t affect our results. Then, we’d have an accurate measure of how much IQ really does affect who makes it and who doesn’t, independent of anything else. By factoring out the influence of the data in Tables 2 & 3 (schooling & class) from the IQ data in Table 1, we can approximate this hypothetical situation. Now we would be left measuring the situation Herrnstein refers to as the pure meritocracy. We have such a situation in Table 7. All that is left of the category Social Class Background in this data is the “pure trait” of intelligence as measured by IQ. Do the results fit with Herrnstein’s vision of a highly stratified society based on differences in IQ? Hardly. Looking at Table 7, it’s clear that such an IQ alone makes very little difference as to what happens to people economically. A person at the high end of the scale would have about the same chance of being at the top economically as a person at the low end, in terms of IQ (10.6/9.4 = 1.07)—about the same as might be predicted by chance. The difference among people in this table are low indeed as far as economic outcome goes. There seems to be very little correspondence between the categories of IQ and economic success, as soon as schooling & class background have been factored out. So, even if your parents had transmitted you their IQ, it alone would have little to do with the money & status you have now. A test score isn’t going to be anyone’s key to success.

Table 7* The Genetic Component of lntergenerational Status Transmission, Assuming the Jensen Heritability Coefficient, and Assuming Education Operates Via Cognitive Mechanisms Alone

The Function of IQ

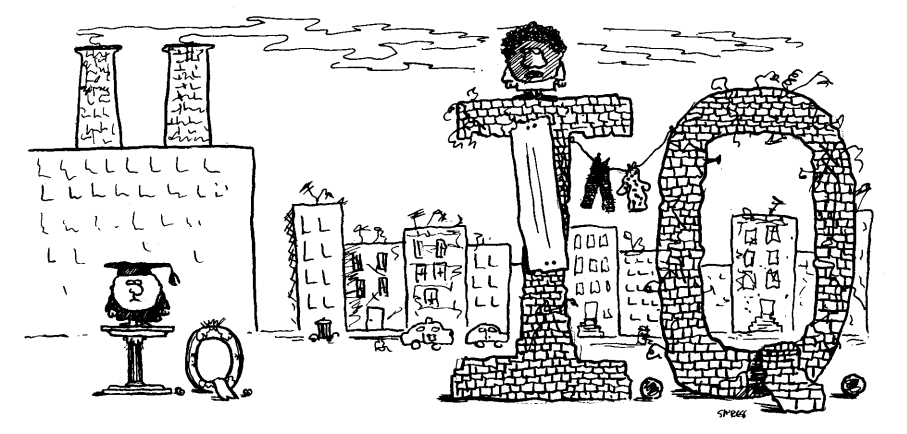

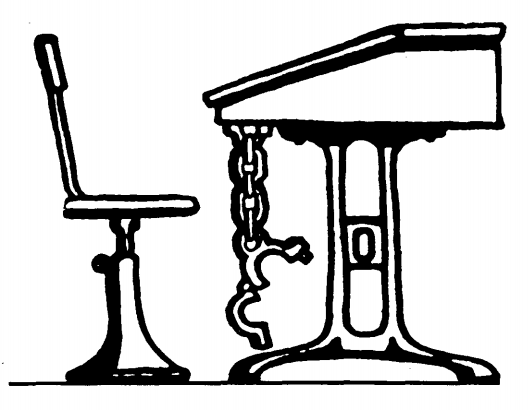

If IQ performance is not the basis for people’s economic success, then what function does IQ serve? The IQ test is one of a battery of devices used in schools to separate kids out and put them into different educational tracks according to their class and racial background. It is a predictor of success and status simply because it is one of the many tools used to maintain the existing class structure in our society. But beyond this, and more broadly, IQ serves to legitimize in people’s minds the unequal way that jobs and wealth are divided. Its use helps to perpetuate the belief that people who are on top got there because they had the intelligence to make it. IQ thus plays an important ideological function.

The need for IQ as an ideological instrument stems from the nature of the U.S. economic and political system. People are raised believing that theirs is a country of democracy and equality, yet every day of their lives they experience a very different reality. Their livelihoods are in the hands of those who purchase and exploit their labor—those who hire, fire, and lay them off at will. Those who determine what their work shall be, what is produced, how fast, in what place, under what conditions. Workers in the U.S. are confronted with alienating and meaningless work and with a heirarchy of bosses who use economic insecurity as their coercive whip. They know exploitation as death from black lung, forced overtime, union busting, the blight of Appalacia, the squalor of urban ghettos.

Work is not democratic and it is not equal. In this advanced capitalist society, work is characterized by extreme division of labor, not only in terms of the fragmentation and specialization of jobs, but also in terms of the division of power and authority. The entire hierarchy, from boss through manager, supervisors and foremen, and worker—on down the line—does not much resemble the democracy and equality that people hold so dear. In the face of such a blatant contradiction, the totalitarian nature of the capitalist form of production must be justified and made acceptable. Ideology must do what force alone could never accomplish.

The justification for this structure, for this system of production, is that it is “technically necessary.” The management and supervision of this massive productive apparatus must be reserved for the few people who have the knowledge and ability to handle the task. Those of lesser skill should be lesser managers, and so on. Higher salaries and status are fair reward for the people who have the training and education to assume positions of power; and these positions, the argument goes on, are won in a fair and freely competitive way by those with merit and intelligence, as measured by and reflected in their years of schooling. Their education is in turn dependent to a large extent on being bright—that is, having a high IQ. Eventually the whole arrangement, from kindergarten through retirement has been justified!

The insidiousness of this argument is that it is more or less believed even though people’s direct experience is not one of being selected simply on the basis of merit or “intelligence.” It is doubtful that experience in the workplace itself could ever make people believe in and accept the way jobs, salaries, and power are determined or distributed. The task of carrying out this ideological indoctrination is the primary function of the educational system, and IQ is one of its tools.

The view that people’s economic success is dependent on their intellectual achievement is created and constantly reinforced in the schools. Schools are seen as oriented toward the production of intellectual skills, rewards (grades) are seen as being objective measures of these skills, and levels of schooling are seen as a major determinant of economic success. The apparent objectivity of IQ—of testing, grading, and tracking—all these experiences, however unobjective and class biased they may really be, begin to reconcile children and parents to the belief that it is “intelligence” that is counted and rewarded.

But while on the surface, the school is oriented toward the development of cognitive abilities, achievement is actually dependent on motivation, perseverance, sacrifice, and a host of other factors related to students social and economic backround. By many years of testing, by gradually “cooling out” students at different educational levels, schools insure that students’ aspirations are brought into line with their probable occupational status. By the time most students finish school they have convinced themselves of their inability or unwillingness to succeed at the next highest level. Through competition, success, and defeat in the classroom, people become reconciled to their class position in our society.

The Role of Education

That schools have served to condition people for their roles within the system of production can be seen from the historical development of education in the U.S. The common notion is that mass education developed as modern industry became so complex, its workings so intellectually demanding, that an increasingly intelligent labor force was needed to run it. But the history of the rise of universal education does not support this view, which puts the cart before the horse. In the West and South for example, mass education began before the growth of skill-demanding industry; it arose rather with the system of wage-labor agricultural employment, before mechanization took place. The development of the modern educational system has in reality grown from a coordinated attempt to provide the U.S. with a disciplined labor force. As a cotton manufacturer wrote to Horace Mann, then Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, in 1841:

I have never considered mere knowledge … as the only advantage derived from a good Common School education … (Workers with more education possess) a higher and better state of morals, are more orderly and respectful in their deportment, and more ready to comply with the wholesome and necessary regulations of an establishment … in times of agitation, on account of some change in regulations of wages, I have always looked to the most intelligent, best educated and the most moral for support. The ignorant and uneducated I have generally found the most turbulent and troublesome, acting under the impulse of excited passion and jealousy.

As capitalism developed in the U.S., as small-scale enterprises gave way to corporations, as farm workers, blacks, and the millions of immigrants swelled the ranks of the urban workforce, and as labor militancy and the public welfare burden developed, the educational system responded to the new demands. For example, as more and more working-class and particularly immigrant children began attending high schools, the older democratic belief in the common school—that the same curriculum should be offered to all children—gave way to the “progressive” theory that education should be tailored to the needs of the child. But in fact, these “needs” were a euphemistic expression for vocational schools and tracking for the children of working-class families. The more academic curricula got saved for those privileged enough to go on to college and white collar jobs. A system of guidance counseling gave a voluntary feeling to this process. Around the same time, as well, the eugenics movement and its theories of ethnic inferiority supplied the rationale for these changing educational programs. And then, mainly after World War I, these developments were finally rationalized by another “progressive” reform —”objective” educational testing; that is, the IQ test.

Thus it is a false notion that the school system has functioned primarily to promote the intellectual skills needed for a technically more advanced system of production (See Andre Gorz, “Technical Intelligence and the Capitalist Division of Labor,” SftP vol V, No. 3, May, 1973). Intellectual skills are more nearly a by-product. What the schools produce is a labor force matched to the demands of the hierarchical division of labor of U.S. productive enterprise. The different levels within this hierarchy demand different worker characteristics, and it is the purpose of the educational system to sort people out accordingly. Not surprisingly these characteristics themselves correspond to various class backgrounds—and so what the educational system actually does is reproduce the existing class structure of American society.

Of course employers don’t directly ask for class background on job forms. But, then, they don’t have to, since the characteristics more acceptable for different kinds of jobs are clearly associated with class status anyway. These characteristics are: personality traits (are you motivated, obedient, tactful, flexible, etc.); ways of behaving (how you look, speak, who you associate with and how); race, sex, and age; and credentials (level of education and work experience). Each one of these characteristics is important in determining where a person will be placed on the job ladder. The inequalities that come from using these characteristics to place people are not the result of irrational and uninformed employment practices. They are necessary. They are used by those in control to keep things working smoothly, and would only be changed by employers if a change would help insure the objectives of profitability and control. These are the traits, then, beyond IQ (inherited or not) that account for a persons economic success. And they are ultimately traits that are identifiable not to individuals alone as much as to social class.

How do people come by the various traits that are needed within the capitalist system of production? Of course race and sex are acquired at birth, and aging is inescapable, thus far. Acquiring credentials means surviving the school system. But the acquisition of the right personality traits and behaviour are largely the results of processing by the school system (and family).

The structure of school is similar in many ways to the structure of the work hierarchy. The different levels of authority in school systems—with their rules, tracking, age divisions, grades and sex distinctions (shop, home economics, physical education)—all make the transition into the workforce fairly smooth. Students develop the traits in school which correspond to those required of them on the job. But, the school experience emphasizes different traits in different students depending on which rung on the job ladder they are headed for. So, for example, the heavy emphasis on obedience to rules and lack of independence in many high schools will fit what an employer needs of someone for rutinized, assembly-line type of work. A four-year college experience, on the other hand turns out a person with different expectations and characteristics. A middle-class suburban high school and a ghetto high school, a four-year college and a junior college, all differ in the traits and behaviors they reinforce.

The different patterns in schools attended by students from different social classes, and even within the same school, are no accident. The educational objectives of administrators, teachers, and parents —and the way kids respond to the various teaching methods and controls) differ for students of different social classes. These differences are strongly affected by economic status: it’s clear that money for schools of working-class and black children is scarce compared to those for the wealthy; so innovative teaching, small classrooms, free time and space, flexible enviornments are much harder to come by. Because of these conditions, kids in poorer schools usually get treated like raw material on the production line—obedience and punctuality are emphasized over creative work and individual attention. And the emphasis, as we’ve seen, corresponds to the traits for the job slots these kids will occupy.

So it is these non-intellectual, non-IQ factors, related to social class experience, that are reinforced by schools and transmitted over generations. They are qualities demanded and used by the structure of work in America; and their influence on an individual’s economic success is decisive. For the very reason class differences exist, efforts to reform schools, create new programs, give more financial aid, etc.—while important demands in and of themselves for children in school—cannot alone change the chances for economic success kids will have.

IQ and Class Structure

Those who attack Jensen, Hermstein, and Shockley, but who don’t attack the idea that “smart people are the ones who make it to the top,” are themselves perpetuating the ideology of IQ. By not analyzing and exposing the origins of the U.S. class structure and the roots of the existing division of labor, they give credibility to the notion that the present system of production and exploitation are ”technically necessary.” When academics and intellectuals fail to attack the systemic basis for inequality in our society, they are really defending their own elitist and privileged positions.

As we’ve seen, the function of education, with the help of IQ, is to achieve the division of labor into workers managers, teachers, housewives, engineers, etc., so necessary for the efficient functioning of the economy. But where do these categories of labor come from? What relationship is there between the system of production and the class stratification that the ideologues of IQ claim is inevitable?

The extreme inequities in this country, whether in income, wealth, access to health care, decent housing, conditions of work, racial discrimination, or any number of others, are not a consequence of the best use of people’s talents, nor the inevitable product of human nature. They are structural features of the system of production. They stem from a form of economic organization in which the vast majority are forced to offer themselves as employees to the small fraction of American people who own and control the resources of the society. The capitalist system of production defines not only the categories of labor, but also its use, according to what is necessary to maintain the vitality and longevity of the present economic system.

This system is organized for maximizing profit, and that includes growth of productive capacity, markets, and economic control. This goal is of prime importance in the manipulation and division of labor, in the creation of wage differentials, and in the limitation of social mobility. Division of labor because specialization means efficiency for the owner of labor, and fragmentation, separation, and powerlessness for the worker. Wage differentials because they provide the incentive for advance. Limited social mobility because it guarantees a reservoir of low cost labor. Unemployment and depressed wages to blacks, women, young people, and other minority groups are institutionalized in the system. The owners and managers hold the power of hiring, firing, establishing production priorities, and disposing of profits. The government, agent of capitalist interest, reinforces these practices through taxes, subsidies, labor legislation, and military force.

These, then, are the roots of social stratification—not intelligence or heredity. To explain the inequalities in our society requires us to understand the social organization and internal dynamics of capitalism. The variety of incentives, the use of IQ, and other methods of manipulating labor are tied up with the ideology which supports and rationalizes this system of production. While these relationships are complex, one thing is sufficiently clear: modern capitalism is abusive, oppressive, and irrational. People labor to produce waste or trivia, and those who produce the least of social value are the ones who reap the greatest rewards—economic and social standing depend on people’s utility to the system and its ruling class, not their utility to other people. Bankers and money handlers manipulate capital, managers manipulate labor, corporate executives manipulate the market, government bureaucrats and executives manipulate people. These servants of capital reap high rewards while people’s needs for food, health care, and decent housing go unmet (unless these generate profit).

People are reduced to mere commodities. Their creativity, humanity, and desire to be socially productive, are drowned in the competitive struggle for economic survival. The actions of both managers and workers are reduced by the demands of capital to mechanistic responses. At worst these actions involve the brutal murder or starvation of large masses of people; at best they mean the institutionalized violence of disease, slum life, and financial insecurity.

It is in the defense of this diseased system that IQ has raised its ugly head. And it is in the destruction of this system—in the struggle to create a humane and just society—that the IQ ideology must be buried. Not only must IQ disappear, but so too must the brutal class system which created it.

— Janet Selcer

WHAT IS THE IQ TEST ??

The material in this article came in part from the Progressive Labor Party pamphlet, Racism, Intelligence and the Working Class.

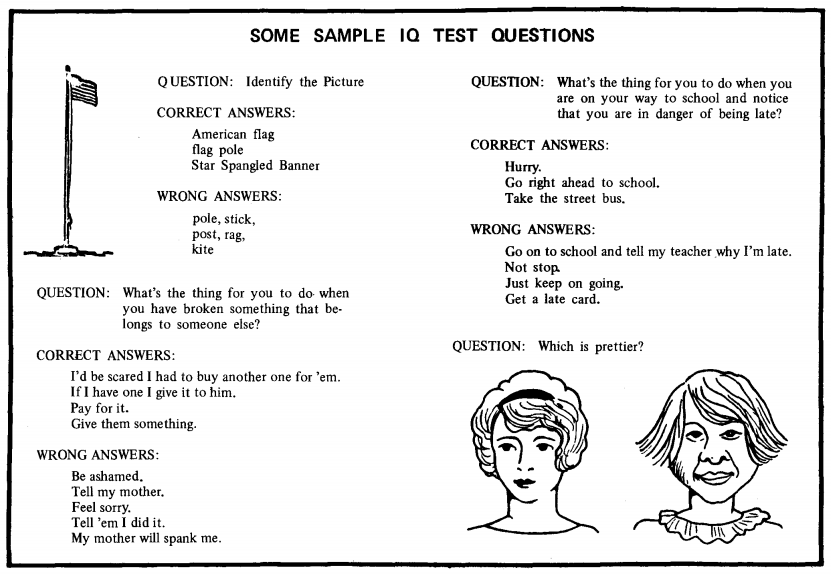

Jensen and his cohorts’ claims concerning the heritability of intelligence are based on measurements of performances on IQ tests. It is assumed that IQ measures some trait called “intelligence” which differs from person to person, and which is an index of success in school and later life. But what, after all, is this “intelligence” except for a measurement of a certain type of behavior, (performance on IQ tests), and how can we say that a certain type of behavior is “correct” or “smart” without considering an individual’s past experiences in similar situations. For example, from the point of view of black working-class children (who go to miserable schools with racist administrators and sometimes teachers as well, who are forced to read books depicting white middle-class people and to learn racist history, and who will probably end up unemployed or in a poorly-paid job with horrible working conditions) what kind of school behavior is “intelligent”? Is it not more reasonable for these children to rebel against the school authorities than to remain docile and work hard at school? When such children are given an IQ test, is it not a completely reasonable response to treat the test and tester as further examples of a racist school system? Obviously such children would not get very high IQ scores, since they would not be motivated to try very hard on the tests, but isn’t that a sign that they are really very aware of the world around them? Deciding what type of behavior is termed intelligent is an extremely political act, and the desired behavior will merely be the kind which is approved of by the prevailing social system.

Political assumptions enter into intelligence testing in even subtler ways than the above. Every type of measurement presupposes some form of distribution of intelligence. For example, it would be quite valid scientifically to develop a test which 99% of the population would pass, indicating that 99% of the population were “intelligent,” and 1% or so were mentally defective. Such an approach would not attempt to find little differences in how people think and behave and translate them into IQ difference, but would assume that intelligence is an attribute of the normal functioning human, while a small proportion of population is retarded. This approach, however, would not be at all useful for those who rule America, because if 99% of the population were about equal in intelligence, why should there not be equality in society as well? Present IQ tests magnify differences among people, and in fact, potential tests which did not reveal these differences have often been rejected.

The reasons for this can be found by examining the people who have made up intelligence tests. Historically they have been racist, anti-working class, and pro-capitalist in their beliefs. Their tests have been designed to rationalize these beliefs, and to show that those who ruled society, and those who did well in it were the best, the smartest, and the most moral people. That the early intelligence testers thought that the ruling class of the time were the most intelligent people in society, and that it was by virtue of this intelligence that they had attained their position is shown in the following quote from Edward L. Thorndike, an educational psychologist.

It is the great good fortune of mankind that there is a substantial positive correlation between intelligence and morality, including good will towards one’s fellows. Consequently, our superiors in ability are on the average our benefactors, and it is often safer to trust our interests to them than to ourselves. No group of men can be expected to act 100% in the interest of mankind, but this group of the ablest men will come nearest to the ideal.3

Not only did the early testers love and admire the ruling class, they also despised and looked down upon the masses, especially the black masses. James McKeen Cattell the father of the testing movement in America and long time editor of Science and Popular Science Monthly expresses these feelings well:

The main lines are laid down by heredity—a man is born a man and not an ape. A savage brought up in cultivated society will not only retain his dark skin, but is likely to have also the incoherent mind of his race.4

Terman, who sired the famed Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, was also a thorough going racist and eugenicist. Further, he predated Herrnstein by 55 years in claiming that occupations and IQ were causally linked. He provided a list of numerous occupations and the corresponding mean IQ, and urged that students with those IQ’s be channeled into courses whose curricula were designed to provide training for the student’s prospective occupation. In this way, IQ became the rationale for inferior and oppressive education for millions of blacks and other working-class children.

As these people identified with the interests of the ruling class, they would obviously try to define intelligence and devise a test which would make those who were rich and powerful come out as the smartest. Francis Galton was one of the first to attempt this. In 1869 he wrote a book called Hereditary Genius, claiming that intelligence was inherited, and that the British ruling class had more of it than anyone else. Eventually he made up a test concentrating on measuring what he thought intelligence was, traits like “memory” and “sensory-motor development,” and tried finally to correlate the results with “eminence” in science and society. His correlations were about zero5 since he could find no skill on which the rich did better than the average British person. This did not stop him, however, from going on to develop new tests. In America James M. Cattell made up similar tests, but for him, too, the correlations between subjects’ scores and success in life ”were disappointingly low.”6

As these people identified with the interests of the ruling class, they would obviously try to define intelligence and devise a test which would make those who were rich and powerful come out as the smartest. Francis Galton was one of the first to attempt this. In 1869 he wrote a book called Hereditary Genius, claiming that intelligence was inherited, and that the British ruling class had more of it than anyone else. Eventually he made up a test concentrating on measuring what he thought intelligence was, traits like “memory” and “sensory-motor development,” and tried finally to correlate the results with “eminence” in science and society. His correlations were about zero5 since he could find no skill on which the rich did better than the average British person. This did not stop him, however, from going on to develop new tests. In America James M. Cattell made up similar tests, but for him, too, the correlations between subjects’ scores and success in life ”were disappointingly low.”6

A further problem for these people was that the early tests did not show black people inferior to whites any more than they showed poor whites as inferior to rich whites. It was often possible, however, to reinterpret test results in order to come to these desired conclusions. For example, R. Meade Bache, in a paper on “Reaction Time with Reference to Race.” found that both Blacks and Indians reacted faster than whites, but claimed that the whites’ “reactions were slower because they belonged to a more deliberate and reflective race.”7 There were a number of other failures of this type which the testers could hardly disguise. A statement by Thorndike in 1903, however, reflects their general attitude: ”The apparent mental attainments of children of inferior races may be due to lack of inhibition, and so witness precisely to a deficiency in mental growth.”8 So much for “objective” science and its results.

This failure to develop a test which would differentiate rich white people from the poor, the black, and the immigrant, was especially significant in view of the trouble racist anthropologists were having at the time. Up until this time, the “turn of the century” theories of racial inferiority had been based upon physical anthropology, the practice of measuring the differences between various groups of people. They measured such things as the ratio of the length of the arms to the length of the body, the ratio of the length of the heel to the leg, the facial angle, the size and shape of the brain, etc.—measurements were designed to prove that blacks were closer to apes than to men. But these theories were beginning to be doubted by many scientists, as well as by the general public. For a time, comparing physical characteristics had been the major method of justifying racism, but by 1909, R.S. Woodworth, Chairman of the Anthropology and Psychology division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science was writing, ”We are probably justified in inferring from the results cited that the sensory and motor processes and the elementary brain activities, though differing in degrees from one individual to another, are about the same from one race to another.”9 Clearly, from a racist point of view a better measurement of racial differences and a better basis of racist ideology was needed. The IQ test’s time had come.

The honor of coming up with such a test belongs to the French psychologist Alfred Binet. Binet’s approach was to avoid an explicit definition of intelligence, and instead to simply assume that whatever intelligence is, it develops with age. If a child performed as well on a test as the average child in his or her age group, then he or she was considered normal. If the child did better on the test than the average in that age group, his or her mental age was said to be greater than the chronological age and visa versa. Herrnstein explains approvingly,

The honor of coming up with such a test belongs to the French psychologist Alfred Binet. Binet’s approach was to avoid an explicit definition of intelligence, and instead to simply assume that whatever intelligence is, it develops with age. If a child performed as well on a test as the average child in his or her age group, then he or she was considered normal. If the child did better on the test than the average in that age group, his or her mental age was said to be greater than the chronological age and visa versa. Herrnstein explains approvingly,

As Binet well knew, the chronological approach to intelligence finessed the weighty problem of defining intelligence itself. He had measured it without having said what it was. It took a while to know whether the sleight of hand had in fact yielded a real intelligence test or just an illusion of one.10

At first it might seem from the above that those who would come out on top in Binet’s test would simply be the more advanced children of their age group, but this is only half the story. The children who came out on top were also the children who did well in school and who were from the upper classes. Were they really the more intelligent children, or were the tests rigged in such a way as to favor the upper classes? The answer is that the tests were rigged, for the test items which were selected were not simply random items nor were they items which simply the majority of children at an age level passed. If the majority passing the item included those students judged by the teacher to be “dull,” and excluded those children judged to be “smart,” the item was not used in the test. Herrnstein explains this aspect of Binet’s method this way:

“He took some children rated by their teachers as the brightest and the dullest in a grade and subjected them to a lengthy series of tests, going from simple sensory discrimination to arithmetic and perceptual speed tests. A number of the tests worked, which is to say they distinguished between the two groups of children.”

The circularity of this method is obvious, Binet’s test merely tested some quality which was approved of by teachers, and the teachers’ opinions were surely based as much on the social behavior and attitude of the children as on their innate “intelligence.” Again we see that the so-called intelligence tests really measure acceptable behavior, and that what is termed acceptable is socially and politically determined.

An example may make this clear. Scores on the Binet test do not correlate well with school success if the tests are taken below the age of six. or seven; therefore from the point of view of the testers, these tests are less “reliable.” Out of the six tests given at age three, four of them are “Copying a circle,” ”Drawing a vertical line,” “Stringing beads,” and “Block building-bridge.” While these items might tell you which three year olds are not doing as well as others chronologically speaking, an upper class, highly motivated child would not enjoy much of an advantage on such tests. Therefore the scores obtained do not generally correlate well with later school success. As a result, these “performance” type tests are dropped from the kinds of tests given to older children. As the testing manual for the Stanford-Binet Scale says,

Many of the so-called performance test items tried out for inclusion in the scale were eliminated because they contributed little or nothing to the total score. They were not valid items for this scale. 11

In other words, when the results on this type of test were checked with teachers’ ratings, they did not match, and the test was discarded. In fact, the better a test was in sorting out the children the more it was used.

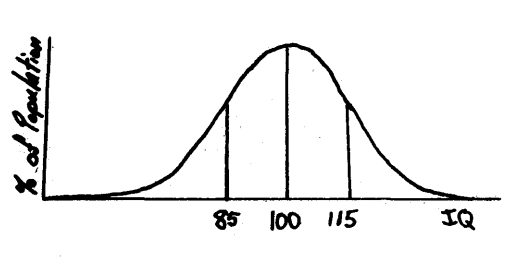

This process of making the scores come out the way the testers want them, with the proper distribution and with the upper class children on top and the lower class on the bottom, is called “standardization.” A test is standardized on a population by adjusting the scores so as to make it come out with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 (see graph). If a test is given to a population and the mean (average) turns out to be less than 100, then the testers change the scoring standards, making it easier and raising the average to 100. The scoring methods, and hence the average scores, can be changed by adding or dropping items that are either too hard or too easy, or by changing the relative value of the different items on a test.

On the original Stanford-Binet test published by Terman in 1916, women were not treated as a separate population and standardized for, and their scores were about 10 points lower than men’s until 1937. Then, for the new version of this test, the means of men and women were compared, and the test was standardized for sex. Questions were added on which women did better than men and some of the ones on- which men did better than women were dropped. In this way the averages for men and women were equalized.12 The decision whether or not to standardize in order to wipe out group differences is a purely political one. Terman decided to eliminate the differences between men and women in the 1937 revision of the test, but the differences between blacks and whites and between upper and working classes have never been eliminated. Why?—Because, claim the testers, the predictive value of the tests would be lessened if black and white, and working and upper class averages were equalized by standardization.

The example of women is again relevant. When women were equalized on the test, the predictive power was lessened then as well. On the revised version of the test, women did as well as men, but because women are not treated equally in society, the test lost some of its ability to predict who would do well and who would do poorly in later life. As long as America is a male-chauvinist society, equalizing male and female scores on IQ tests will lower the predictive value of the tests. In just the same way, as long as racism keeps black people in the worst jobs at the lowest rates of pay, any attempt to equalize black-white scores will lower the predictive power of the test. This shows that the tests are designed to reflect prevailing class relationships and to prove that those on top are smart and those on the bottom are dull. Tests can be designed to reflect anything the designer wants, and racist and anti-working class assumptions have guided and determined the results of the IQ test.

In summary, we can see the following weaknesses and fallacies in the IQ tests.

- “Intelligence,” as measured by these tests, is never defined, but as we have seen is related more to behavior than to any innate quality. The desired behavior, such as ”willingness to conform and obey,” “respect for authority,” etc., is determined by ruling class norms and ideals.

- Questions on IQ tests are “loaded” to favor middle and upper class children. Tests which do not distinguish between groups are discarded.

- The tests were in fact designed with the express purpose of finding differences between people or groups of people. Differences in performance can be eliminated (men vs. women), so that the differences being measured are not absolute, but depend on the questions being asked. The decision of whether or not to eliminate any group differences is purely a political one.

— Susan Conrad

HERITABILITY: A SCIENTIFIC SNOW JOB

Jensen, Shockley, Herrnstein and the other ideologues of racial and class inferiority have claimed that scientific studies show that intelligence is largely inherited, that performance on IQ tests is determined mainly by genetic factors. By cloaking their ideological pronouncements in scientific garb, by talking about “correlations of IQ test scores,” “heritability,” and so on, they have sought to ward off those not familiar with such language and lend scientific authority to their statements. In fact the arguments used by Jensen and his cohorts are merely distortions and lies put forward as scientific evidence.

The scientific touchstone of the Jensen gang is a concept called heritability (Jensen says the heritability of IQ is 80%). As we shall see, heritability is a rather well defined and limited concept in genetics, but its advantage for Jensen is that it can easily be confused with what is more commonly thought of as inheritance. To bring out the contrast between these two different concepts, let’s look first at what is meant by inheritance.

You inherit things from your parents (and past generations of parents)—things like black skin, or a long nose, or the color of your hair. These are physical traits that are largely independent of where you grow up or the kind of manners you are taught. They are thought to depend on the genetic material, DNA, which you also inherit from your parents (50% from each). But the main point is that what you inherit are characteristics that don’t really change much with the environment you grow up in (though people have been known to get sun tans and nose jobs). Of course you also inherit poverty (wealth), social class, and other aspects of your parents socio-economic position and life style.

Now, what is meant by heritability? This technical concept grew out of the practical needs of livestock and plant growers to increase their yields. A simple example will help make it clear. Suppose you are an agribusiness person from Iowa who grows corn. You notice that on your farm some plants have long-eared corn, others have shorter length ears. Does it make sense for you to select out and breed the long-eared corn for your farm? Well, if the variations in ear length of the corn on your farm is due to the fact that many genetic varieties are present, and that some of them grow better on your farm, then it would make sense to try to breed those with long ears. On the other hand, if the corn plants on your farm consist of a small range of genetic varieties, and the variation in ear length depends mostly on differences of soil, or moisture, or fertilizer, etc., then it would not make sense to breed the long-eared corn. (You’d be better off trying manure or bug spray.) In the first case where the variations in ear length are mainly the result of genetic factors, we would say the heritability of ear length is high. In the second case where the variations in ear length are mainly the result of environmental effects, we would say the heritability is low. What heritability measures13 is the relative importance of genetic factors in producing the variations in a particular trait (ear length) in a particular population (the corn on the farm) in a particular environment (the Iowa farm). Technically speaking, heritability of a trait is the proportion of the total variation in that trait within a given population within a given range of environment which comes from genetic causes.14

Knowing the heritability in the context we’ve given above can be useful, but otherwise the concept has severe limitations. Since heritability only has meaning for a given range of environments, it tells nothing about what would happen if the range of environments were changed. The same field of corn growing through a warmer summer might have a totally different distribution of ear length among the plants. Also, heritability tells us only about the given population—it says nothing about a different population (of corn) or of the differences between any two such populations. We cannot correctly talk about the heritability of a trait per se; heritability only has meaning in reference to a specified population (with a specified history) in a specified environment.

Let’s see how the Jensen gang perverts this concept and confuses it with inheritance. Jensen has claimed that the heritability of IQ is high in white, middle-class population (let us not contest this for the moment15) and then has concluded from this that intelligence is inherited, that is, that it is fixed genetically, and unchangeable. Thus, he says, the 15 point difference in average IQ scores between whites and blacks is genetic in origin, and compensatory education (i.e., improved schooling) is doomed to failure, since some people are just born stupid. None of these conclusions can be correctly drawn, and to demonstrate the elementary fallacies in the reasoning, let us consider the following two examples:

- Take 100 sets of new born identical twins (identical twins have exactly the same genetic material). Split each pair of twins so that we have two groups, A and B, of 100 unrelated babies each. Raise group A in the best environment money can buy—good food, books, sensory stimulation, attention, etc. Raise group B in a poor environment—poor clothing and housing, a near-starvation diet, rats, and other conditions which poor working class children are subjected to. Suppose after five or six years, we give IQ tests to both groups and find that children in group A have an average IQ of 120, those in group B 60. Further, we can imagine that we can measure the heritability of IQ in each group, and let us say for the sake of argument that in both groups A and B the heritability of IQ for that group is 100% (that is, any variation is genetic since all were treated exactly the same in each group). Does this mean that the IQ difference between the two groups is genetic? No, it can’t be because the individuals in group B are genetically identical to those in group A. The flaw in this reasoning is that we measure the heritability within each group, but not for the sum of the two groups—everyone in both A and B. This example applies directly to Jensen’s argument. The Jensen gang uses heritability estimates obtained from white, middle class people and go from there to conclude that the observed IQ differences between blacks and whites in the U.S. population as a whole are inherited. As we have seen in the above example, however, IQ differences between two populations in different environments have nothing to do with the heritability within either one of those populations.

- Most babies thrive on milk, but a few with a real genetic abnormality suffer severe mental retardation on a milk diet. Remove the responsible ingredient (milk sugar), however, and all do equally well on a milk diet. On a whole milk diet we would find that mental retardation had high heritability, since all children with the abnormal genes would be retarded. On a diet without milk sugar, however, the children with the abnormal genes would be able to develop their mental ability. Note that the childrens’ genetic material would not have changed—only their environment. Thus even if a trait is highly heritable in one environment, the development of the trait and the heritability can be changed by altering the environment. In terms of the IQ question, no matter what the heritability of IQ were, it would still say nothing about the feasibility of compensatory education. Jensen, as we have seen, incorrectly argues that since IQ is largely “heritable” there is no use trying to change it by educational methods.

The arguments used by Jensen and his cohorts, the equating of inheritance and heritability’ are completely fraudulent. By using technical language they have attempted to cover up the misconceptions and fallacies in their work. In arguing the scientific basis of their conclusions, they are distorting the most elementary notions of genetics.

All of which might lead us to ask what light the advances in genetics over the last thirty years can shed on this issue. It seems that genetics has nothing more to say than that nothing can be said. No one has ever discovered the relationship of complex behavior patterns in humans like IQ performance to specific genes, in fact this hasn’t even been done for fruit flies (which have been extensively studied). But even fruit flies have proved to be rather complicated organisms, so the study of genetics has been carried out more recently on a molecular level. If anything, these studies have shown the complex nature of the interactions between the environment and genetic material. So intertwined are these two aspects of biological development that breaking them down into separate identifiable parts has not been possible. What this means in practice is that in looking at the variation of a particular trait within a given population, it is not really valid to consider that variation as arising independently from genetic causes and environmental causes. The total variation is not merely the sum of an environmental variation and a genetic variation. Or put another way, the use of a concept like heritability which assumes such an arbitrary division is itself highly questionable.

We see that advances in genetics indicate that the studies of the Jensen gang have no basis at all in what has been learned by geneticists; and even more importantly, no studies in the conceivable future would be able to link IQ performance to a person’s genetic makeup. The question is an ideological one, only raised by Jensen and his cohorts to perpetuate an old form of political oppression.

— Stu Flaschman and Al Weinrub

THE CASE FOR ZERO HERITABILITY

Jensen claims that the heritability of IQ is high. But work that we and others have recently done clearly refutes this claim, and in fact leads us to the conclusion that there is no genetic component to variation in IQ performance at all. We will briefly summarize the relevant kinds of studies and we will hopefully succeed in demystifying Jensen’s procedures so that people will be able to see for themselves why the studies are evidence in favor of zero heritability without having to rely on “expert” opinion to make the arguments.

The actual studies are not difficult to understand but considerable mystification exists because of the use of the concept of heritability. The heritability of IQ performance refers to whether there is a genetic component to individual differences in IQ scores (see previous article). Zero heritability means that individual differences in IQ performance are due entirely to differences in environmental factors such as social class, geographical location, birth order and the like.16 Clearly genetic material, DNA, is implicated in everything any human being does from eating to taking IQ tests. But just as one would expect a zero heritability of eating habits (i.e., individual differences in eating habits are a question of upbringing and adaptation) there is a zero heritability of IQ performance because IQ tests are simply a passport to middle class jobs and as such test (white) middle class habits of speech, perception and upbringing.

As for the studies themselves, we will review three kinds of studies, two of which involve twins. The idea behind using twins to study genetic differences is as follows. Identical twins have identical genes whereas fraternal (sexist terminology) twins only have 50% of their genes in common. If it can be shown that identical twins are more similar to their partners in IQ score than fraternal twins are to their partners then this difference could be interpreted. as being due to the extra genetic similarity of identical twins. Likewise if identical twins raised apart (that is, in different environments) have more similar scores than a random pair of the same age, same sex, same social class, etc., then this extra similarity could be interpreted as being due to the genetic similarity of the separated twins.

Every study used in this kind of work is based on the same principle. One examines pairs of individuals and if they prove to be more similar in IQ scores than some control group the extra similarity is assumed to be genetic in origin. The faults in all the studies are that other factors such as similar age, similar sex, similar appearance, similar social class and similar geographical location all produce similarity in IQ scores. One or more of these factors has been ignored in every study purporting to show a high degree of genetic similarity in IQ performance.

Here is a breakdown for the major kinds of studies: 17

- Identical Twins Raised ApartJensen claims that the similarity in IQ scores of identical twins raised apart is due to genetic similarity. Leon Kamin has recently reanalyzed the actual data on which Jensen bases these claims.18 Kamin’s work shows that the similarity is accounted for by the following factors: (1) In the study by Cecil Burt the data was extensively tampered. Burt assumed that IQ was genetically determined and this bias influenced not only the design and interpretation of his experiments, but also the data he collected. (2) In Shield’s study 27 out of 40 of the separated twins were placed in the homes of close relatives and a number of the remaining 13 were given to close friends; in other words, they were all placed in similar environments,19 thus negating environmental effects. (3) In the remaining two studies random pairs of the same age are as similar in their scores as the separated identical twins.

- Comparison of Identical and Fraternal Twins 20Jensen assumes that in those cases where identical twins are more similar to their partners in IQ score than fraternal twins are to their partners the extra similarity is due to the extra genetic similarity of the identical twins. All studies of this type suffer from ignoring the fact that identical twins are treated more similarly than fraternal twins. Identical twins are of the same sex, look alike, are frequently dressed alike and in general receive far more similar treatment than fraternal twins do. These treatment effects are large. For example consider fraternal twins of the same sex compared to fraternal twins of the opposite sex. Twins of the same sex are more similar in their IQ scores than twins of the opposite sex. This extra similarity in their IQ scores is due solely to similarity of treatment and it is as large as the extra similarity observed between identical and fraternal twins in six out of eight of the studies cited by Jensen in his original paper. 21

- Studies of Adopted Children and Their Foster Parents 22Jensen’s claim for these studies is that adopted children are less similar in IQ scores to their foster parents than natural children are to their natural parents. Kamin has shown however that in families with one adopted child and one natural child the adopted child is as similar to the parents as the natural child is to the same parents. Such a finding is concrete evidence in favor of zero heritability.

All these studies point to zero heritability of IQ performance. In addition there is another class of studies consisting of identical-fraternal comparisons that show no difference between identical and fraternal twins. In general such studies are either ignored or not reported. As Scarr-Salapatek, one of the workers in this field, describes it 23:

There are few published reports of null results unless a major theoretical point is at issue. I, for or one, obtained the same [results] for blood grouped identical and fraternal twins on an individually administered test of non-verbal IQ and and did not submit the results for publication (because no one would believe that the identical twins were not more similar, there were only 60 pairs and so on.

However, there is too much information in her published report24 of the IQ scores of twins in Philadelphia for this results to stay hidden. A straight forward analysis25 of her data shows that there is no significant difference between identical and fraternal twins for any race or social class grouping of the entire school population, grades kindergarten through twelfth grade, in the Philadelphia school district. Quantitatively Scarr-Salapatek’s data gives an upper limit to the genetic component of variation (the heritability) in IQ performance of 15% ± 16%. This result is consistant with zero heritability. All other studies cited to support high heritability of IQ performance are consistent with this low figure because of the large environmental effects that have been ignored as discussed above. Thus for identical-fraternal comparisons the identical twins are sometimes more similar than the fraternal twins because they are treated more alike. Thus for identical twins raised “apart” the identical twins are similar because they have actually been raised close together or because they are similar in age (non-standardization of the tests for age). All the studies are actually evidence in favor of zero heritability of IQ. Every one can be understood in terms of particular pairs receiving similar treatment with zero genetic component. It is not a question of “a little of this” (genetics) and “a little of that” (environment). Every single study used to support high heritability of IQ performance is either consistent with zero heritability or is direct evidence against the heritability of IQ performance. The reason for a zero genetic component to IQ variation is that the test tests (white) middle class habits of speech and perception, and variations in these habits are a result of variations in the social class and upbringing of the individuals who are forced to take them (see article on IQ Tests, pg. 17).

Conclusion

Some previous work attacking Jensen concedes that a genetic component to IQ variation exists. Such a concession is not only wrong it is weak. Statements to the effect that everyone is equal, they just have different talents; society needs diversity; etc., tend to reinforce racist, sexist and class divisions. Buried in the idea of equal but different is the existence of a line down the middle26 with someone on top and someone on the bottom each knowing their place. The equal but different argument concedes too much. In the context of a class society equal but different means everyone knows her /his place.

Granting the genetic part of the argument (or else hysterically denying that such an argument can even be made) is itself an example of how deeply prejudice has penetrated our minds. Jensen’s work has had great impact because it sounds plausible—not 80% perhaps, but why couldn’t there be racial, sex, and class genetic differences in IQ? Shoddy, superficial and wrong arguments to this effect slip by because we sneakily think maybe blacks are different, maybe women are better suited to careers in the arts, not the sciences. Jews made it why not other ethnic groups. When Jensen comes out with “scientific” support for this, the reported “differences” are accepted as real or else arguments are made that such studies are impossible. We ourselves were reluctant to confront the studies directly because deep down we were afraid they might be right even if, when all was said and done, environmental factors would prove to be more significant than “inate” factors. The effects of racism, sexism and class division are very deep. Zero heritability puts the issue squarely back on politics. Genetics is a convenient no struggle position; it’s now being used to handle all kinds of “intractable” problems; racism27, crime (the so-called XYY syndrome)28, schizophrenia29, and compulsive eating and obesity in women30 (fat is a feminist issue, don’t you know31).

But there should be no misunderstanding. We are not saying that since IQ performance is not inherited, give black people, working class people an “enriched environment” and they too will score high on IQ tests. Such arguments accept the validity of testing, i.e., the present social structure. It is not a question of enriched environments. Our goal is not to let those who can become upper class but to abolish the upper class altogether because it is exploitative and criminal in its relationship to the great mass of working people.

And there is a final point to be made. It’s about intelligence. Anthropologists32 have argued for years that is is impossible to define intelligence without reference to language and culture. This is the material basis for intelligent behavior. One acts “intelligently” in the context of a language and culture. An oppressive culture creates its own intelligence and we should never forget this.

Personal Conclusion

This nation was built by slave and immigrant labor. Every generation has faced the same ideology—slaves who ran away supposedly had drapetomania33, a blood disease; immigrants were inferior, they had big lips, subhuman intelligence 34, they were polluting the white race—no Irish need apply, dirty Wop, dirty Kike, dirty Nigger, dirty Spik—the vile names and the crimes committed by a vicious and brutal capitalist system from 1776 to 1976; Slavery, genocide of the American Indian, generations of sweat shops on Seventh Avenue and on the Lower East Side, Welsh coal miners in Pennsylvania, Irish railroad workers, Chinese gold miners in California. The solution to America was the same for all—try to pass for white, speak good English and become American. Generations of first born Americans were ashamed of their parents’ accents and tried to pass for white—America the Melting Pot—jump in and get smelted.

But there is another tradition. Those that didn’t pass for white. Tom Mooney, Sacco and Vanzetti, Eugene Debs, Emma Goldman, Malcolm X, our parents, people who didn’t buy the mythology, communists, traitors to the Great American Dream, who brought revolutionary struggle to America.

— Susan Orbach, Joel Schwartz, & Mike Schwartz

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 2 <<

NOTES

- Another way of looking at the numbers in the slots should be to say that of 100 people who are in the highest 10th of the population for IQ, 30.9 or about 31 of them will also be in the highest 10th economically. Or going to the far right side, only .6 people out of 100 who have an IQ in the lowest 10th of the population will also be on top economically.

- The perfect symmetry of the numbers in these tables occur because the results from the sample population are first calculated into a general correlation coefficient, and based on that number, then projected into the table’s specific slots. The mathematics involved serve to give this balanced appearance, though the results are nearly exactly like the actual distribution of people for such a survey would be. We should also realize that the population used for these facts is one comprised of “non-Negro” males, aged 25 to 34, of nonfarm background. While that’s obviously a selected & unrepresentative group, it nonetheless represents the dominant labor force in this country. So it’s the one into which minority groups and women would have to integrate to get an equal chance by currently established standards. In this sense, it’s an ironically appropriate group.

- Thorndike, “How May we Improve the Selection, Training, & Life-Work of Leaders?” Addresses Delivered before the 5th Conference on Educ. Policies (N.Y., Teachers College, Columbia Univ., 1939) p. 32.

- James McKeen Cattell, James McKeen Cattell: American Man of Science, Vol II, (Lancaster, Pa., 1947) 165.

- Shultz, History of Modern Psychology (N.Y., 1969).

- Shultz, p. 121.

- R. Meade Bache, “Reaction Time with Reference to Race,” Psychological Review, Vol. II, No. 5 (Sept. 1895) 474-486.

- Thorndike, Educational Psychology (New York, 1903).

- R. S. Woodworth, “Racial Differences in Mental Traits,” Science, Vol 31, (1910) 179.

- Hermstein, IQ in the Meritocracy (Boston, 1973) 67-67.

- Merrill & Terman, The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Manual, (Boston, 1960), 8.

- Merril & Terman, Measuring Intelligence (Cambridge, 1937). 34.

- Note that if all the corn had the same length, that is, if there were no variation heritability would have no meaning. If everyone had blue eyes you couldn’t determine the heritability of blue eyes. If this seems odd, remember that we are not talking about inheritance.

- In this article we do not discuss the methods for determining heritability. Interested readers can consult a standard text on genetics.

- In the following pages, Jensen’s claims of high IQ heritability are refuted and the case is made for zero heritability.

- Even as sophisticated a commentator as linguist Noam Chomsky falls into the trap of arguing that IQ can’t have zero heritability since we know genes contribute to brain development, and hence to intelligence. The point is that it’s not genetic influence that gives a trait high heritability—it is genetic differences in the trait among the population that gives high heritability.

- Jensen originally wrote a seven page paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 58, 149 (1967) reviewing the literature on the IQ scores of identical twins raised together and fraternal twins raised together. He then blew this up into a 123 page paper at the invitation of the Harvard Educational Review, 39, 1 (1969) by adding 115 pages of explanation and a sketchy 9 page review (pp 50-59) of the studies of identical twins raised apart and other categories such as studies of adopted children and their foster parents. The overwhelming majority of studies (22) is in the first category while there are only four studies of separated twins and four studies of adopted children and their foster parents. Recent citations in the literature emphasize the first two types.

- Kamin, L.J., Invited Address, Eastern Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., March, 1973.

- Note that the different environments for identical twins are limited from the start. Having black skin certainly makes the environment of U.S. society different than it is for a white person, but have you ever seen.a twin pair where one was black and the other white? These differences never show up in identical twin studies; black skin is a genetic difference and thus any effect of skin color on IQ would increase the heritability of IQ!

- Schwartz, M. and Schwartz, J., Nature (in press).

- Jensen originally wrote a seven page paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 58, 149 (1967) reviewing the literature on the IQ scores of identical twins raised together and fraternal twins raised together. He then blew this up into a 123 page paper at the invitation of the Harvard Educational Review, 39, 1 (1969) by adding 115 pages of explanation and a sketchy 9 page review (pp 50-59) of the studies of identical twins raised apart and other categories such as studies of adopted children and their foster parents. The overwhelming majority of studies (22) is in the first category while there are only four studies of separated twins and four studies of adopted children and their foster parents. Recent citations in the literature emphasize the first two types.

- Kamin, L.J., Invited Address, Eastern Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., March, 1973.

- Scarr-Salapatek, S., Science, 178, 236 (1972) Letters.

- Scarr-Salapatek, S., Science, 194, 1285 (1971).

- Schwartz, M. and Schwartz, J., Nature (in press).

- Mitchell, J., Women’s Estate, (Vintage, New York, 1972) p.161.

- Jensen, A.R., Harv. Educ. Rev. 39, 1 (1969).

- McClearn, E.E. in Annual Rev. Genetics, 437 (1970) (Annual Reviews, Inc., Palo Alto).

- Ibid.

- Bruch, H., Eating Disorders, (Basic Books, New York 1973) p.26.

- Susie Orbach and Carol Munter, Fat is a Feminist Issue, WBAI-FM, April 24, 1973.

- Bohannon, P., Science, 181, 115 (1973) Letters.

- Ehrenreich, B. and English D., Complaints and Disorders. The Sexual Politics of Sickness. Glass Mountain Pamphlet No.2 (The Feminist Press, Box 334, Old Westbury, N.Y. 11568).

- Kamin, L.J., Invited Address, Eastern Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., March, 1973.