This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Technological Dependence: Patents and Transnational Corporations, emphasis on Chile

by Daniel Zuck & James Cockroft

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 4, July 1973, p. 4 – 12

abridged from a chapter in Dale L. Johnson, ed., The Chilean Road to Socialism (Spanish Edition), Mexico City: Fonda de Cultura Economica, 1973.

abridged from a chapter in Dale L. Johnson, ed., The Chilean Road to Socialism (Spanish Edition), Mexico City: Fonda de Cultura Economica, 1973.

Who pays royalties to Cervantes and Shakespeare? Who pays the inventor of the alphabet, who pays the inventor of numbers, arithmetic, mathematics? In one way or another all of mankind has benefited from, and made use of those creations of the intellect that man has forged through history… We state that we consider all technical knowledge the heritage of all mankind and especially of those peoples that have been exploited.

Fidel Castro

29 April 1967

The purpose of this analysis is to explore the relationship which the less developed countries (LDC) have with the United States, Europe, and Japan concerning technological dependence. This dependence, engendered by the patent system along with the sale and distribution of technology by transnational corporations, further contributes to the drain of capital:—already scarce—from these countries. Special attention is given to Chile because that nation’s policies of economic nationalism represent a potentially critical challenge to the forces of technological dependence.

Outright stock ownership is the usual means of economic plunder by transnational corporations. However in the less developed countries where conditions of economic nationalism prevail, majority ownership can become secondary in importance. This is because nationalization of strategic industries can succeed only if dependence on foreign technology is eliminated, since this dependence allows continued foreign control over decision-making and profit. Thus, under conditions of assertive nationalism, the older methods of exploitation—via ownership—tend to be replaced with newer ones more suitable to the moment.

In describing technological dependence, we directed our attention to patents, social class, and the culture of technology, because of their primacy in today’s imperialism. If an LDC is to escape perpetual technological dependence, it must combat the ruling elite which bases its power and life style on links to foreign technology, and also deal with the underlying value system which accompanies the importation of foreign technology (including middle-class concepts of affluence and the myth of technological expertise).

An important factor in creating or perpetuating dependence is the comparative cost of technology. Most LDC’s find that developing original or alternate sources of technology costs more than purchasing the already existing technology as sold by large transnational corporations.1

While economic nationalism may modify certain aspects of dependence, underdeveloped economies which suffer from a relative shortage of investment and human capital tend to be run on the basis of short or medium-run cost effectiveness. Such nations build on what is already available or convenient, and they usually import technology sold by transnational corporations. Even nationalistic LDC’s advancing towards socialism, such as Chile, can readily remain locked in dependence on the capitalist world.2

Patents and Oligopolies

A patent is the legal affirmation of a corporation’s or person’s exclusive right to use a technological process to produce a good or service. According to international law, patents registered in one country are not applicable abroad. If a company fails to take out a patent on its equipment in a country where it operates, someone else can “re-invent” the same or similar equipment and patent it there. Ownership of a patent means a transnational corporation can control conditions for the sale of technology to an LDC, or the use of that technology there by other firms. A transnational corporation that holds a patent can choose who may have access to “its” technological process; stipulate how the technology may be used; and fix the costs for using it. Legal permission to use a patented process is called a license, and the associated fees are termed royalties. The transnational corporation may (and often does) demand that the licensee confine marketing to a single country. Thus, there is no competition with the transnational corporation’s operations in other countries.

Patents thus convert a technological process deriving from new ideas and research into a. form of private property used at the owner’s discretion. Because technology is already developed in the industrialized countries, and this usage of patents is accepted, LDC’s basing their economies on short-run costs do little technological research and development (R & D), as compared to the United States and other industrial centers. R & D in the United States for 1975 is projected to reach $40 billion, far more than any single LDC’s gross national product.3

Deliberations for the acquisition and sale of technology depend on the number of patents or the amount of original experimentation done in the past by any two negotiating parties. For transnational corporations negotiating with each other, this is not a serious problem.4 When bargaining with LDC’s on the other hand, transnational corporations are in the highly favorable position of oligopoly, as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has suggested:

The majority of patents are owned not by individual inventors but by large transnational corporations. The latter use patents for their global business policy … For example, 50% of all patents which were obtained by companies and whose corresponding research was financed by the Federal Government of the United States between 1946 and 1962 belong to twenty firms … market control and monopolistic concentration is reinforced through the system of cross licensing between companies, which in tum reduces a worldwide oligopolistic structure into a regionally monopolistic one.5

Because of their advantageous positions, these large transnational firms can charge LDC’s exorbitant prices for their technological hardware and licenses for its use. This exacerbates already unfavorable terms of trade between LDC’s and developed countries, terms under which LDC’s buy dear and sell cheap.

Whether or not a transnational corporation will spend the time and money to take out a patent on its invention in an LDC is determined in part by its own estimation of whether or not its bargaining power will be hurt by the amount of original skills being developed within the LDC. This means that a transnational corporation keeps a sharp eye on the local universities and research centers so that they won’t undercut the foreign corporations bargaining power in the country by patenting a competitive invention on their own. It also means that a transnational corporation must continuously examine statistical compilations of patents in an LDC, government regulations on trade and investment, consumer tastes, advertising needs, and similar matters.6

Table 1: Percentage of Total Patents Granted Which are Foreign in Origin 1957-19617

| Large Industrial Countries | Smaller Industrial Countries | Developing Countries | |||

| USA | 15.72% | Italy | 62.85% | India | 89.38% |

| Japan | 34.02% | Switzerland | 64.08% | Turkey | 91.73% |

| Fed. Rep. of Germany | 37.14% | Sweden | 69.30% | Egypt | 93.01% |

| United Kingdom | 47.00% | Netherlands | 69.83% | Trinidad and Tobago | 94.18% |

| France | 59.36% | Luxemburg | 80.48% | Pakistan | 95.75% |

| Belgium | 85.55% | ||||

Transnational corporations want to control the conditions under which they can license technology to LDC’s. They want to retain their monopoly on technology. Thus, they denationalize LDC patent activity. A limited number of corporations is expanding control over technological processes to an increasing number of countries. Tables 1-3 demonstrate how completely foreigners have penetrated, denationalized, and taken over patent activity in selected countries.

Table 1 shows that 90% or more of patents granted in representative LDC’s are foreign in origin. This compares with only 16% foreign patents in the United States and 63% in Italy (1961). The United States has maintained its advantageous positions in patent activity since 1940, as compared with the other major industrial powers in the capitalist world. The United States is the only capitalist nation to retain clear-cut control over its own patent activity. Table 2 reveals that private companies account for the bulk of patents registered in Chile between 1955 and 1969, and that foreign corporations account for over 90% of all registered patents by 1969 (compared to about 70% in 1955). Table 3 makes the trend toward denationalization even more manifest—from 65.5% foreign in 1937 to 94.5% in 1967.

Table 2: National and Foreign Patents Registered in Chile8

| 1955 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | |

| Total Patents of all types | 547 | 883 | 430 | 496 | 590 | 739 | 1290 | 1107 | 1182 |

| Total Foreign Patents | 478 | 828 | 402 | 451 | 552 | 699 | 1229 | 1045 | 1110 |

| Total National Patents | 69 | 55 | 28 | 45 | 38 | 40 | 61 | 62 | 72 |

| Total National and Foreign Patents Registered by Enterprises | 403 | 739 | 371 | 423 | 510 | 644 | 1111 | 949 | 1076 |

In developed countries, on the other hand, great amounts of R & D work prevent such extreme denationalization. Meanwhile, the relative lack of experimentation in LDC’s makes it easier for foreign enterprises, especially those from the United States, to penetrate them. D.S. Gorman, President of Western Electric, confirms the importance of foreign patenting:

Western Electric handles all the foreign patenting for all the Bell system in addition to our own domestic patenting. Currently the Bell system has almost 9,000 patents in the United States and more than 10,000 in foreign countries.

Now, using just one year as tin example, this involves some 2,500 patent applications. Of these about seventy per cent are duplicates filed in patent offices outside the United States. It takes an organization of 18 full-time professionals in our company to oversee this foreign operation. We also hire the services of patent agents in foreign countries to submit and prosecute our cases in full compliance with local practice. The cost of this foreign patent operation is running close to $2 million a year.9

The patent division of the transnational corporation is considered so strategic to its ability to control the sale of technology that in 93 companies surveyed in the U.S., roughly one-third (31) had their patent divisions directly subordinate to one of the firm’s top executives. 10 These patent departments use the strategy of “defensive patenting” to ease future licensing or direct penetration, or to protect existing and future export markets from potential competition by national firms of other countries. Defensive patenting generally prevents a competitor from using the invention , and thus impairing the enterprise’s own current or planned production. 11 In Peru, of 4,872 patents granted between 1960-1970 in major industries, only 54 (about 1 %) were actually in use. During the same year in Colombia, of 3,513 patents registered in major industries, only 10 were then in use. Defensive patenting occurs in almost all of Latin America’s industrial sectors. As the UNCTAD study notes, “the repercussions of this lack of competition could imply significant price increases, with negative income and balance of payments effects on the countries concerned.”12

Table 3: Percentage of Patents Granted in Chile According to Origin13

| National | Foreign | |

| 1937 | 34.5% | 65.5% |

| 1947 | 20.0% | 80.0% |

| 1958 | 11.0% | 89.0% |

| 1967 | 5.5% | 94.5% |

This is not a static situation, however. Most corporations are now more interested in exporting investment capital than in exporting manufactured products· to Latin America; their investments in industrial sectors in many LDC’s are rapidly increasing. According to The Rockefeller Report on the Americas, U.S. direct investment in Latin American manufacturing industry increased during the 1960’s from one-fifth to one-third of all U.S. investments. In many previously undeveloped sectors, transnational corporations often have secured monopoly control of markets by prior patenting. an-d continuing control of developed technology.

In the case of Chile, in 1969, forty-seven large foreign companies controlled 53.7% of the total number of patents registered that year by all foreign and national companies.14 A sample of foreign-owned subsidiaries surveyed in Chile revealed that 50% “had a monopoly or duopoly position in the host market.”15 The UNCTAD study suggests that foreign corporations divide markets among themselves: “arangements of patent cross-licensing among transnational corporations, cartel agreements, tacit segmentation of markets … (etc.) often constitute common behavior rather than the exception.”16 By 1970, more than 100 U.S.-controlled corporations, with investments worth over $1 billion, were operating in Chile.17 Twenty-four of the top 30 U.S.-controlled transnationals were involved. Two-fifths of Chile’s largest 100 corporations were under foreign control, while many more are under foreign influence because of the oligopolistic control exerted by the transnational ‘giants’ over markets and technology. Among these giants, the American ones have a dominant position. The U.S. accounts for more than two-thirds of the total receipts based on patents and licenses accruing to the capitalist nations most actively involved in patents.

Patents as First Line of Foreign Penetration

Table 4: Foreign Penetration of Chilean Economy18

| Investing Country | Number of Licenses | Total Volume of Foreign Direct Investments (1964-1968 inclusive) |

Total Volume of Foreign Private Loans (1964-1968 inclusive) |

Total Receipts, Intermediate and Capital Goods, from Royalties and Profits in 1969, corresponding to 399 technology contracts |

| USA | 178 | $43,103,000 | $120,299,000 | $16,349,000 |

| Fed. Rep. of Germany | 46 | 14,517,000 | 28,181,000 | 4,238,000 |

| Switzerland | 35 | 2,941,000 | 18,250,000 | 3,949,000 |

| United Kingdom | 30 | 2,264,000 | 8,121,000 | 3,896,000 |

| France | 17 | 6,051,000 | 2,606,000 | |

| Canada | 25,161,000 | 4,789,000 |

Table 4 further shows the position of United States with respect to receipts from technology contracts. The United States far outranks its competitors in amount of licenses, direct investment, and loans. The relationship between licensing technology and direct foreign investment is one of mutual reinforcement.19 Furthermore, the case of Chile illustrates that the employment of patented technology precedes the eventual takeover of a nationally controlled corporation. Historically, a U.S.-based transnational corporation has penetrated a market like Chile’s roughly as follows: First, there is a small direct investment; second, generous amounts of credit are offered (in most cases coming from capital generated within the foreign country of operation); third, a patented process is provided, and a testing period ensues. This technology in and of itself may unleash productive forces which will eliminate competition and virtually conquer the market. Once the market is conquered and tested out for future profitability, the transnational corporation can increase control by taking over any remaining competing national companies, by participating with local capital in joint ventures, or, optimally, by setting up its own subsidiary to send not only royalties but all profits directly to the parent company. In Chile, the copper fabricating and explosives manufacturing industries illustrate how the transnational corporations that received the largest amount of royalties also were responsible for the major provisioning of technology and had majority ownership of the corresponding Chilean subsidiaries. Thus, the monopoly privileges inherent in the existing patent system supply one of the instruments with which foreign companies can acquire national companies through foreign investment.20

Transnational corporations concentrate patenting in strategic areas of Chilean industry (Table 5). Transnational corporations originally patented in these areas of the Chilean economy in order to restrict production to themselves. But they also use patents to circumvent the threats of nationalism, as John R. Shipman has explained in the Harvard Business Review:

If management desires to expand the company’s manufacturing facilities in a country whose government is controlling expansion, the fact that an expanded facility would make available to the economy products protected by the company’s patents and therefore not otherwise available may assist materially in working out an arrangement satisfactory to the government.21

Since the Chilean government legitimizes transnational corporate control over technology, by granting them patent privileges inside Chile, Chilean tariff laws to protect new industry become less meaningful.

The transnational corporations sell technology in packages; the purchase of part of the package is made difficult if not impossible, and extremely costly. Each particular piece of technology is necessary for the continued operation of the productive process. Therefore, the transnational corporations are assured control of the production in the LDC’s economy by the monopoly of technological supply in the strategic sectors. UNCTAD explains that “know-how represents a part integrated in a larger whole”.22 However, it is not “know-how” as neutral technology that is included in packages, but the capitalist production system itself masquerading as an objective science. Such non-competitive conditions also serve to rebuff all but the most complete nationalist threats (as in present-day Chile, where the refusal to continue technological supply is causing serious bottlenecks in the economy).

Table 5: Percentage of Patents in Selected Economic Sectors Registered in Chile by Foreign Corporations23

| 1962 | 1965 | 1968 | |

| Chemicals, Rubber and Coal Derivatives | 93% | 99% | 97% |

| Machinery, Metallurgy | 71% | 81% | 78% |

Transfer Pricing and Technological Dependence

One major advantage that a transnational corporation has is its ability to carry out, between its subsidiaries in different countries, dealings that frequently allow evasion of taxation or other legal restrictions. By manipulating the prices charged for machinery, technological services or final products, soid between affiliates of the same company, the actual operating profits and assets of any particular subsidiary can be altered at will, compensated by corresponding modifications in the books of other subsidiaries or the parent company. This flexibility enables a global corporation to minimize the overall impact of taxes or other regulations it must deal with. (Of course most such constraints are mild to begin with due to the influence of business over government in general). In short, anything traded among a parent company and its subsidiaries, including raw materials or management consultation, can involve this procedure, called transfer pricing. “By underpricing exports and/or overpricing imports a subsidiary can extra-legally transfer earnings to another location in the world.” 24 Some countries, like Chile, tax corporate earnings at a relatively high rate. These taxes however can be substantially reduced by underpricing goods exported to subsidiaries in countries with low corporate taxes, like Panama or Puerto Rico. At the same time, a company’s imports into a high tax area can be overpriced so that the local subsidiary can show higher costs and thus lower taxable profits on its books. Similarly, laws limiting the repatriation of profits (removal in hard currency to, for example, U.S. owners) as, again, in countries like Chile, can be overcome by transferring funds via transfer pricing to other countries, like Argentina, which have weak laws. Another motivation for overpricing imported capital goods by transnational corporations is to inflate the book value of their investments thereby allowing higher depreciation and hence lower taxes. Overvaluation by ITT of its investments in the Chile Telephone Company was a principal issue in the government’s move against ITT.

A total of 40%-60% of all Latin American trade comes under potential transfer pricing. U.N. data illustrate the impact of transfer pricing on imports:

In the Colombian pharmaceutical industry a sample taken indicated that the weighted average overpricing of products imported by foreign owned subsidiaries amounted to 155% while that of local firms was 19% … Smaller samples taken in the same industry in Chile indicated an overpricing of imported products in excess of 500% ….

Similarly in the electronics industry in Colombia comprehensive samples corresponding to firms that controlled about 90% of the market indicated overpricing which ranged between 6% and 69%.25

A study of 258 exporting firms in 10 Latin American countries, representing 25% of the region’s manufacturing exports, reveals the magnitude of the capital losses from export transfer pricing. The average undervaluation of exports was 45% representing “a loss in foreign exchange earnings of almost $500 million which for 1970 was roughly 4% of officially recorded total exports”. 26

In most LDC’s the choice has been made to rely heavily on foreign investment and technology, typically provided by transnational corporations. The sale of capital goods and technological know-how has therefore become a key avenue for transfer pricing, siphoning capital out of the LDC’s. As UNCTAD points out:

For the whole of Latin America it has been estimated that during the period 1960-1965 about $1,870 million were spent annually for the importation of machinery and equipment. These imports amounted to 31% of the total import bill of the area. They also constitued about 45% of the total amount spent by Latin America on capital goods during the same period. For individual countries this relationship amounted to 28% for Argentina, 35% for Brazil, 61% for Colombia and 80% for Chile.27

The UNCTAD study goes on to estimate that about “one-third of total imports of machinery and equipment in Latin America are made by foreign-owned subsidiaries”.

Patents as a Last Line of Defense

Transnational corporations of course prefer the freest possible access to investment opportunities in LDC’s, using whatever technology and capital best suited to their global plans. There is however some opposition, even from the local capitalist elites. Increasingly often transnational corporations have had to conform to strict new laws requiring for example joint ownership,-minority foreign ownership, or even expropriation. The existence of technological dependence of course plays a strong deterrent role in these matters, as Roback points out in the Columbia Journal of World Business: “When a firm’s Research and Development capability is located outside of a high political risk country, expropriation would be self-defeating because it would cut off the flow to the subsidiary of badly needed technological know-how”.28 Nevertheless, the transnational corporations are planning ahead for the “new nationalism sweeping the third world”. A recent report Nationalism in Latin America by Business International (BI, a consulting firm for transnational corporations) cites an OAS document which suggests “that a new era of international investments has dawned, in which the predominant characteristic is the exploitation of technology, as opposed to the previous one, which was frequently abusive, characterized by the exploitation of the natural resources of the country.” The BI report goes on to argue:

Transnational corporations of course prefer the freest possible access to investment opportunities in LDC’s, using whatever technology and capital best suited to their global plans. There is however some opposition, even from the local capitalist elites. Increasingly often transnational corporations have had to conform to strict new laws requiring for example joint ownership,-minority foreign ownership, or even expropriation. The existence of technological dependence of course plays a strong deterrent role in these matters, as Roback points out in the Columbia Journal of World Business: “When a firm’s Research and Development capability is located outside of a high political risk country, expropriation would be self-defeating because it would cut off the flow to the subsidiary of badly needed technological know-how”.28 Nevertheless, the transnational corporations are planning ahead for the “new nationalism sweeping the third world”. A recent report Nationalism in Latin America by Business International (BI, a consulting firm for transnational corporations) cites an OAS document which suggests “that a new era of international investments has dawned, in which the predominant characteristic is the exploitation of technology, as opposed to the previous one, which was frequently abusive, characterized by the exploitation of the natural resources of the country.” The BI report goes on to argue:

control of technology is just as important as control of equity, and easier for a foreign firm to wield, since it permits penetration without the least exposure to the vicissitudes and controls of the local market… If licensed technology and management contracts can afford sufficient income and control without equity ownership, all the better in terms of economic nationalism … Be prepared to bend on equity. Sometimes it is better to settle for only 25%, with a management contract or a tight licensing agreement to control technology and marketing, rather than insist on a majority. This would defuse nationalist charges that foreigners are drawing out unjust profits, since the local partner will get the bulk of the profits while you are well compensated for services demonstrably rendered.

In fact, BI goes so far as to suggest to its clients that they “examine the possibility of accepting exports from licensees in lieu of royalty payments”.29

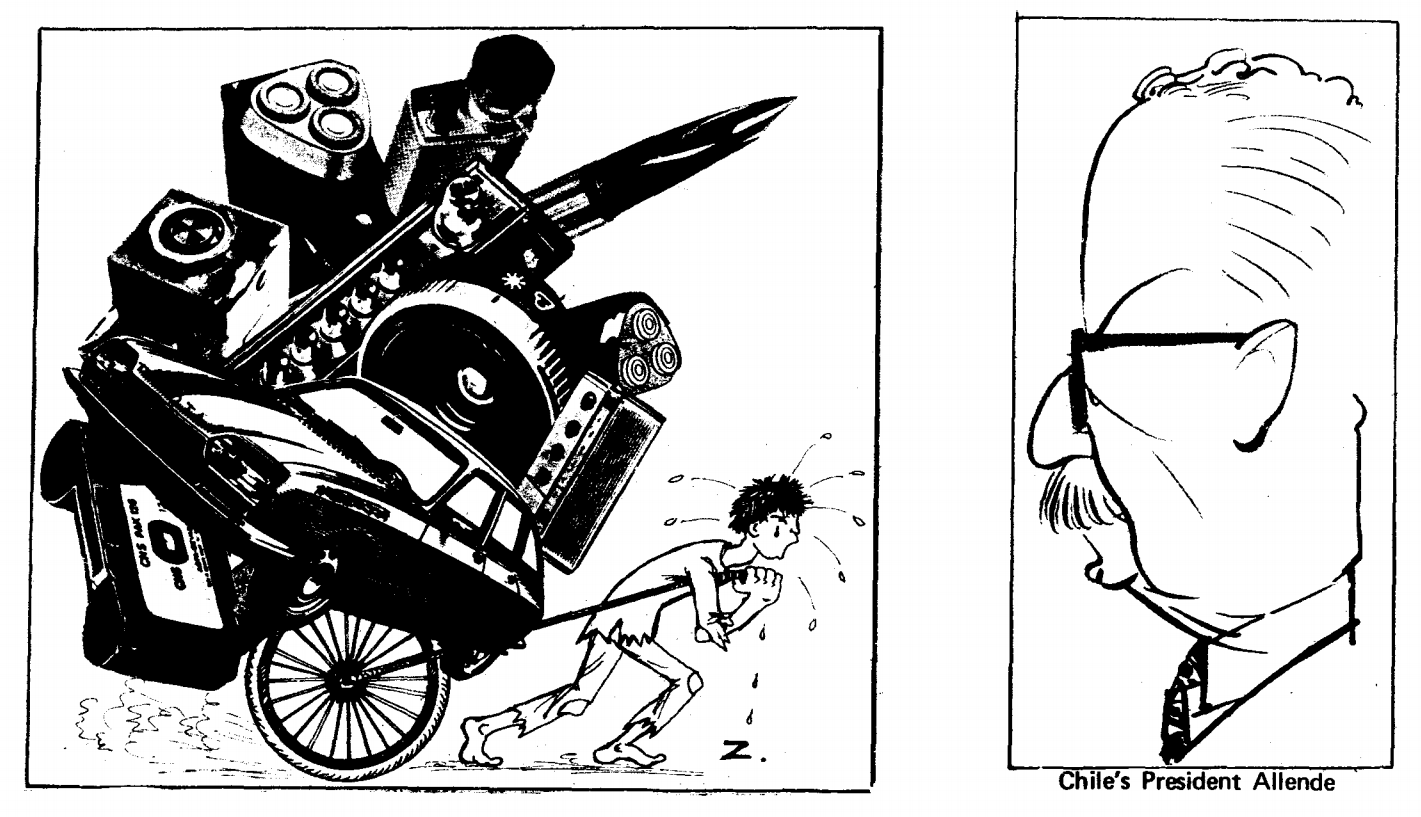

This is especially significant in the case of Chile, since its government has threatened to prohibit all future royalty payments. Indeed, most of the transnational corporations operating in Chile, while favoring the Allende government’s overthrow, may nevertheless be prepared to adjust to the new status quo, if Chile’s incipient socialism cannot be reversed. This obviously applies less to ITT, Kennecott and Anaconda whose assets have been or will be nationalized. Others, such as R.C.A., Armco Steel and Cerro Corporation however are. trying “not only to remain, but to strive to promote formulas of association with the government”.30 That transnational corporations can sustain a comfortable involvement in LDC’s even in the face of seemingly serious challenge is an indication of the hold they have, at least partly through technological dependence, over the LDC’s. As Rodman C. Rockefeller of International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC, a Rockefeller family non-oil investment hustle in Latin America) explained to a meeting of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR, see p. 21) “it is not unsatisfactory to do business with Marxists once a basis of export and import conditions have been established”. 31

Regional Integration, Diversification and Technological Dependence

Many development-minded government technocrats in Latin America especially the Peruvian military elite (!) see regional integration such as put forward in the Andean Pact as a defense against transnational corporations and a stimulus for development. The Andean Pact supposedly will prohibit defensive patenting. However for this integration to be effective, all the participating countries would have to pass and enforce strong anti-monopoly laws since penetration of any one of these countries means penetration of all of them as internal tariffs are removed. This is not the case, as exemplified by Colombia which has a weak law on defensive patenting.32 Thus the creation of the Andean Common Market is not viewed as a disaster by the transnational corporations. They are already pitting one Andean country against another and carefully choosing where they will place their particular patents and investments. BI calls this a “rationalization strategy”: “remove present export restrictions on selected licensing agreements to enable licensees to export to nearby markets now being supplied from other sources:’33

Some developmentalists, especially among Chilean technocrats, see the diversification of trade and sources of imported technology as a greater hope for advancement. They have come to realize, furthermore, that diversification within the capitalist world, to include European competitors to U.S.-based transnationals is not sufficient. However, within the current framework, even were Chile to find alternative technology on better terms from ‘socialist’ countries, there would still remain the problems of “conditions”, patents, foreign ‘know-how, repairs and parts, shipping costs, familiarizing workers with new technology and operation manuals, etc.

The Cult of Technocracy

Patents and associated business practices of transnational corporations form the essential basis of technological dependence. There is a social and cultural dimension to technological dependence which perpetuates the problem. Deriving in the first place from the lopsided class structures within LDC’s and the international stratification of wealth and power, technological dependence permeates, even shapes, the very structure of social classes and the consciousness of different class groupings within LDC’s.

In most LDC’s, patented technology is used to produce goods for a small percentage of the population who can afford them, rather than to meet the most important needs of the majority of the people. Items which the ruling elite and upper-middle and middle income groups can afford to consume are what are generally copied and produced. Foreign standards of production and consumption generate a materialistic, consumer-oriented elite and middle strata which increasingly imitate the life styles of affluent families in the more developed countries. Besides basic industry, many small businessmen are also dependent upon the presence of transnational corporate technology and are locked into its productive process through partial ownership, management, sales, or services. LDC elites and middle strata come to define the continued presence of such technology as being within their own class interests. Their life style is shaped by the technology that allows it to exist and is reinforced by a form of ideological, or cultural, dependence characterized by the “cult of technocracy.” 34 As in the “advanced” countries, technology is portrayed as a neutral benevolent force. Reliance on “experts” is encouraged, especially among the technocrats many of whom are caught up in the language and practice of U.S., European and Japanese technology and trade.

In most LDC’s, patented technology is used to produce goods for a small percentage of the population who can afford them, rather than to meet the most important needs of the majority of the people. Items which the ruling elite and upper-middle and middle income groups can afford to consume are what are generally copied and produced. Foreign standards of production and consumption generate a materialistic, consumer-oriented elite and middle strata which increasingly imitate the life styles of affluent families in the more developed countries. Besides basic industry, many small businessmen are also dependent upon the presence of transnational corporate technology and are locked into its productive process through partial ownership, management, sales, or services. LDC elites and middle strata come to define the continued presence of such technology as being within their own class interests. Their life style is shaped by the technology that allows it to exist and is reinforced by a form of ideological, or cultural, dependence characterized by the “cult of technocracy.” 34 As in the “advanced” countries, technology is portrayed as a neutral benevolent force. Reliance on “experts” is encouraged, especially among the technocrats many of whom are caught up in the language and practice of U.S., European and Japanese technology and trade.

The case of the automobile industry in Chile illustrates this point. On October 19, 1971, the government announced: “Nine foreign firms have been competing to win a government auto contract. These foreign firms are Fiat, Peugot, Pegaso, Nisan, Volvo, British Leyland, Citroen, Fap Famos, and Renault. Those firms that win the contract will produce the autos and will form a joint venture with CORFO [the Chile Development Agency], in which CORFO will have majority interest.”35 Allende’s government has since started to produce small and intermediate size cars for “popular” consumption. An expansion of roads and parking facilities has resulted, although a study by an American economist, David Barkin, has shown how “the automotive program is incompatible with a progressive program of income distribution… The tendency [to produce cars and construct parking lots] would exacerbate the existing inequalities rather than facilitate structural change.”36 The technicians, social planners, economists, engineers and similar professionals—many of whom consider themselves to be revolutionary—who suggested the above plan for Chile are so wedded to modern technology and immersed in the internationally honored system of patents that they tend to limit their options accordingly and thereby become one of the more influential human forces inside Chile in continuing Chile’s dependence. The most influential force within Chile perpetuating dependence, of course, remains the bourgeoisie itself.

The cult of technocracy is a crucial ideological creator and perpetuator of economic dependence because it so elevates and mystifies technology as to make independent experimentation next to impossible. Workers and peasants are excluded from control over technology and made to feel “unprepared” to tackle technological questions, even “at the local level of broken parts, repairs, etc.

In almost every case where the Chilean Government has moved against U.S. transnational corporations, the corporations were allowed to retain their control over technology.37This has been true with such corporations as General Tire and Rubber, Armco Steel, Dow Chemical and others. Dependence is thus being maintained in Chile on both an economic and ideological level.

Furthermore, the cult of technocracy, and the technocrats who officiate over it, can serve as a potential power base for reactionary ideas to build upon. The cult of technocracy aids the transnational corporations by encouraging Chileans to continuously look towards the metropolitan countries as an answer to their problems.

The elimination of technological dependence through the patent system is an essential part of the process of radical social change. However, even countries whose class configurations are radically changing find it difficult to surmount the ideological problem of the “cult of technocracy”. For example, the Chinese, by their own accounts, confronted problems of relying too heavily on the expertise of Soviet technicians in the 1950s. And a decade later, during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, one of the major ideological directions of the revolutionary process was the struggle against dependence on China’s own “experts” with a renewed revolutionary emphasis on “self-reliance” at every level of society, including that of the technocrats themselves, who were instructed to go “to the people, in order to learn from the people.”

Based on our research, we conclude that patents—technology as private property—are an inherent feature of the capitalist social order which is itself based on an oppressive class structure. Genuine development in the interest of the working people, with technology in the service of the people, will occur only when that class configuration is dissolved and, in the process, the patent system eliminated.

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 4 <<

NOTES

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- To an extent, the same problem of technological dependence might be indicated within the socialist world, insofar as we may judge, for example, from the Chinese polemic against the Soviet Union’s aid program in the 1950’s. However, our primary concern here is with economies based on cost and capitalist market relations, especially Latin American and the metropolitan capitalist countries.

- Yu. A. Sergeyev and N. Y. Strugatshya, “Scientific and Technical Development, the Monopolies and the Patent System,” reprinted from Russian Research Journal S.Sh.A.: Ekonomik, Politika, Ideologiya in Idea, v. 15, no. 2 (Summer, 1971).p. 327. It should be noted that private U.S. corporations that have been granted research funds from U.S. federal agencies retain all patents corning out of such research, except in cases where the contracts for the R&D are concluded with the Atomic Energy Commission or NASA. The General Electric Corporation has thus been able to obtain 471 patents at the expense of U.S. taxpayers (p. 328). According to George Summers, representative of Fairchild Industries, Inc., more than half of all R&D funds in 1971 came from the federal sector ($15.5 billion out of $27.8 billion), mainly the Defense Department. See his address at the Proceedings of a Special Conference on Technology, reprinted in Idea, v. 15, no. 3 (Fall, 1971) p. 451.

- John R. Shipman, “International Patent Planning,” Harvard Business Review, March-April, 1967.

- UNCTAD, “Oligopoly” is defined as “A market situation where independent sellers are few in number. Neither the monopolist nor the purely competitive firm must consider how alternative actions by rival fums will affect its own revenue possibilities — the monopolist has no rivals and the competitive fum has so many that it can ignore any one of them. Oligopolists not only have rivals but they have so few of them that each is large enough to affect the others significantly. Their prices, outputs and other relevant variables are therefore interdeterminate.” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1968 ed.), p. 283.

- John R. Shipman, “International Patent Planning,” Harvard Business Review, March-April, 1967.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Alvaro Briones, “Los conglomerados transnacionales y la integracion del sistema capitalista mundial: el caso chilena” (Working Document, Centro de Estudio.s Socio-Economic, Facultad de Ciencias Economicas, Universidad de Chile, 1972). Briones’ data utilized here and later in this analysis have been published, in summarized form, by Chile Hoy, no.’s 31, 33, and 34 (Jan. 12-Feb. 9, 1973).

- Cited in Thomas Ritscher, “Foreign Patent Applicationsand Patents” Idea, v. 13, no. 1 (Spring, 1969), p. 133.

- Yu. A. Sergeyev and N. Y. Strugatshya, “Scientific and Technical Development, the Monopolies and the Patent System,” reprinted from Russian Research Journal S.Sh.A.: Ekonomik, Politika, Ideologiya in Idea, v. 15, no. 2 (Summer, 1971).p. 327. It should be noted that private U.S. corporations that have been granted research funds from U.S. federal agencies retain all patents corning out of such research, except in cases where the contracts for the R&D are concluded with the Atomic Energy Commission or NASA. The General Electric Corporation has thus been able to obtain 471 patents at the expense of U.S. taxpayers (p. 328). According to George Summers, representative of Fairchild Industries, Inc., more than half of all R&D funds in 1971 came from the federal sector ($15.5 billion out of $27.8 billion), mainly the Defense Department. See his address at the Proceedings of a Special Conference on Technology, reprinted in Idea, v. 15, no. 3 (Fall, 1971) p. 451.

- Industrial Property, monthly review of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the United International Bureau for the Protection of Intellectual Property (BIRPI), Geneva, Switzerland, no; 9 (September, 1972).

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Alvaro Briones, “Los conglomerados transnacionales y la integracion del sistema capitalista mundial: el caso chilena” (Working Document, Centro de Estudios Socio-Economic, Facultad de Ciencias Economicas, Universidad de Chile, 1972). Briones’ data utilized here and later in this analysis have been published, in summarized form, by Chile Hoy, no.’s 31, 33, and 34 (Jan. 12-Feb. 9, 1973).

- UNCTAD. The word “monopoly” may be defined as “unified or concerted discretionary control of the price at which purchasers in general can obtain a commodity or service and of the supply which they can secure or the control of price through supply as distinct from the lack of such control which marks the ideal situation of perfect competition,” Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1930 ed.) pp. 623-630. Duopoly or bilateral monopoly can be described as a market situation wherein “a monopolistic buyer purchases from a monopolistic seller, in which two requisites of production jointly demanded are (separately monopolized)” Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, (1930 ed.) v. III, p. 628.

- UNCTAD cartel “designates an association based upon a contractual agreement between enterprises in the same field of business which while retaining their legal independence, associate themselves with a view to exerting a monopolistic influence on the market.” Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, (1930 ed.), v. III, p. 234.

- James D. Cockcroft, Henry Frundt, and Dale L. Johnson, “The Multinationals,” in Dale L. Johnson (ed.), The Chilean Road to Socialism (New York: Doubleday-Anchor, 1973). Revised and expanded in Spanish as “Las companias multinacionales y el gobierno de Allende,” in Huerquen-Boletin de Noticias del Banco Central de Chile, no. 4 (Nov. 20, 1972) and Punta Final, v. VII, no. 171 (Nov. 21, 1972); also, Siempre (Mexico City), Sept. 13, 1972.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- John R. Shipman, “International Patent Planning,” Harvard Business Review, March-April, 1967.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- Alvaro Briones, “Los conglomerados transnacionales y la integracion del sistema capitalista mundial: el caso chilena” (Working Document, Centro de Estudio.s Socio-Economic, Facultad de Ciencias Economicas, Universidad de Chile, 1972). Briones’ data utilized here and later in this analysis have been published, in summarized form, by Chile Hoy, no.’s 31, 33, and 34 (Jan. 12-Feb. 9, 1973).

- Ronald Mueller and Richard Morgenstern, “Economic Evidence of Multinational Corporate Behavior: Transfer Pricing and Exports in Less Developed Countries”. Unpublished manuscript, Fall, 1972. Copy available on request from Professor Ronald Mueller, Department of Economics, American University, Washington, D.C.

- UNCTAD. “Overpricing” in this context is defined as the following ratio: 100 x FOB prices on imports in Andean countries (A), minus FOB prices in different world markets (B), divided by FOB prices in different world markets (B), thus, 100 x (A-B)/B. This takes into account the fact that transfer pricing of technology by transnational corporations on a global basis can result in overpricing of technological imports by national firms in Latin America.

- Ronald Mueller and Richard Morgenstern, “Economic Evidence of Multinational Corporate Behavior: Transfer Pricing and Exports in Less Developed Countries”. Unpublished manuscript, Fall, 1972. Copy available on request from Professor Ronald Mueller, Department of Economics, American University, Washington, D.C.

- Junta del Acuerdo de Cartagena, Transfer of Technology, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Secretariat (UNCTAD), TD/107, December 29, 1971.

- H. Robock, “Political Risk: Identification and Assessments,” Columbia Journal of World Business, July-August, 1971, p. 14.

- Business International Corporation, Nationalism in Latin America, September, 1970.

- Chile Hoy, Nov. 24-30, 1972, p. 11.

- Cited in NACLA’s Latin America and Empire Report, Nov. 1971.

- Industrial Property, no. 5 (May, 1972), p. 130 (extract from Article of the Colombian Patent Law).

- Business International Corporation, Nationalism in Latin America, September, 1970.

- The concept “cult of technocracy” is a visceral one familiar to any worker having to approach a government bureaucrat, engineer, doctor, or plant manager, as well as to intellectuals who have studied problems of industrialization, technology, and economic development. There already exists an abundant literature on the impact of technology upon people’s value systems and daily lives. We employ the concept “cult of technocracy” for many reasons. First, it is a “cult” because so many people have come to accept its dynamics of expertise, specialization, unique skills, and unquestionable authority, on a level of both “common sense” and respect, admiration, or worship. Second, it is a “technocracy” because a cross-section of classes and personnel exists which in effect behaves as a technologically shaped and informed group which carries out tasks from positions of power and authority both in government and in economic production. Third, it is an ideological phenomenon because so many people accept, believe in, and live by the cult of technocracy, however severe the frustration or alienation which accompanies it. The cult of technocracy is especially applicable to an analysis of Western countries and LDC’s dependent upon advanced capitalist nations. Many so-called “Third World” countries, such as China, North Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, and Tanzania, have developed ideologies which attack the cult of technocracy with varying degrees of success. However, as the case of the Soviet Union suggests, the introduction of ‘socialism’ is no guarantee that the cult of technocracy will disappear merely by the elimination of capitalist modes of production.

- Presidencia de la Republica, Oficina de Informaciones y Radiodifusion, Calendario del Area Social (nov. ’70-abr. ’72), p. 8.

- Emphasis added by David Barkin, “Automobiles and the Chilean Road to Socialism,” in Dale L. Johnson (ed.), The Chilean Road to Socialism (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1973).

- Robinson Rojas, El imperialismo yanqui en Chile (Santiago: Ediciones MI, 1971), p. 88.