This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Science Teaching: Towards an Alternative

by Boston SESPA Teaching Group

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1972, pp. 6 – 10

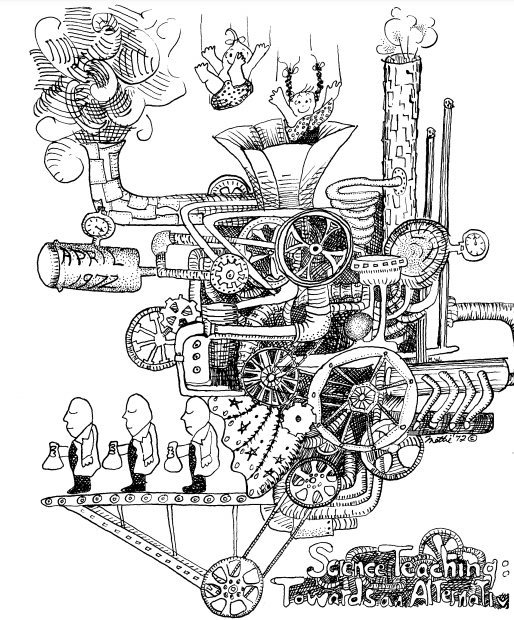

We begin our special issue on science teaching with excerpts from the pamphlet Science Teaching: Towards an Alternative. This general critique of science teaching was distributed at the April meeting of the National Science Teachers Association in New York. The activities of the SESPA Science Teaching Group at the meeting are described in the next article (Up Against the NSTA, p. 11). The eight-page pamphlet with the cover illustrated on the opposite page (by Mettie) is available from SESPA at 15 cents/copy or less for quantity orders.

In the last few years many of us have begun to question various aspects of our jobs as teachers. In part this has been due to an awakening consciousness among all teachers about the authoritarian nature of schools and the socializing function they perform. It has been due also to the broad recognition now that continued growth of science and technology may be at best a mixed blessing in our present society. And it has been due also to our difficulty to motivate students and interest them in the science we teach. Of course, all these problems are related to one another in the end, and we have been trying to uncover the basic thread tying them together, and in so doing to find alternatives that will make our teaching more rewarding.

In the last few years many of us have begun to question various aspects of our jobs as teachers. In part this has been due to an awakening consciousness among all teachers about the authoritarian nature of schools and the socializing function they perform. It has been due also to the broad recognition now that continued growth of science and technology may be at best a mixed blessing in our present society. And it has been due also to our difficulty to motivate students and interest them in the science we teach. Of course, all these problems are related to one another in the end, and we have been trying to uncover the basic thread tying them together, and in so doing to find alternatives that will make our teaching more rewarding.

What kind of students leave our classrooms? Are they critical, free-thinking individuals who have learned to respect and understand one another and to work together and act for their common good? Or are they mute, compliant youngsters who have learned how to respect authority and to compete with each other for the limited positions they are being schooled to fill? Granted these are stereotypes, but is it not the nature of the schools and of the curriculum to produce the latter, and does it not require the exceptional teacher, working against the educational system, to produce the former? Our experience, our frustrations, leave little doubt in our minds.

The reason lies simply in the fact that an educational system reflects the purposes of the society it serves. In America we have a highly competitive society built around certain myths of freedom, choice, democracy, and justice in which most people because of the nature of the social and economic system live, in fact, in a state of financial insecurity and political impotence. The schools are meant to maintain that system. They generate and reinforce the popular belief that poverty and alienation are the result of people’s own stupidity-rather than products of this society’s social and economic structures. But that’s not the worst of it. The schools perpetuate the social class, race and sex role divisions in American society. Through IQ, aptitude and personality testing, through a multitude of teaching mechanisms and many other discriminatory means, students are ticked off, one against the other, according to the system’s definition of ability and achievement. The school’s occupational channelling thus fosters competition among youngsters for positions in what many people now recognize as an irrational, hierarchical, and largely oppressive occupational structure. And of course, in providing these functions, it is not the role of the schools to shatter the Great American Dream with nightmares of genocide, poverty, racism, sexism, political repression, and other forms of institutional violence and injustice.

To make these rather general statements more specific, suppose we look at science education per se. How are the materials, methods, and curricula geared toward perpetuating the values and structure of our present society? Consider first the training of the scientist. In the classroom and laboratory the myth of an apolitical, benevolent science prevails. Graduate school, and often undergraduate education, involves a near total submersion of the student in technical material with little if any historical or philosophical perspective. Research productivity is the measure of worth as the student acquires skill in a specialized field. Technical questions are isolated from their social and economic context (e.g., the use of science) except for perhaps consideration of the prestige and financial status of the researcher. Thus the end product of this training is a narrow specialist-one taught to perform scientific miracles without considering their political implications—a reliable tool of the power structure.

Another aspect of this training is an ingrained sense of elitism. Courses are designed to select and seperate out potential scientists from their fellow students. Those who. succeed are led to view themselves as members of an elite intellectual class. They take patronizing and condescending views of other people’s opinions and aspirations, an attitude which reveals an underlying commitment to undemocratic structures. The elitism emerges for example when scientists attribute social problems to incompetence and irrationality—with the implication that a few intelligent people who really understand technology could solve all the problems (technocracy).

The training just described is, of course, only the final stage of a very long educational process begun in grade school. Not surprisingly, the early educational experience is instrumental in developing those values and attitudes which become important later on. We find that elementary and high school science teaching strongly reflect the character and needs of the advanced training programs. This is not surprising since part of their function is to recruit and prepare individuals for scientific careers.

Note for example the large number of curriculum reforms and new programs which have been generated in the U.S. since Sputnik. This large-scale curriculum development. was funded as part of a broad program of support of science through agencies such as NSF, NASA, NIH, and the large foundations, and was closely coordinated with increased levels of support by the Pentagon. These programs were designed to produce the technical manpower necessary for the development of an ever more sophisticated war machine.

But the effect of such programs has been to profoundly influence how science is taught in the schools. The curricula are geared to preparing students for professional study. They emphasized basic theory and mathematics to the near exclusion of practical science, that is, the understanding of how everyday things work. For example the PSSC physics curriculum was designed for a narrow segment of high school students for the purpose of getting them to think like scientists and thus instill in them the values of working physicists. It was designed largely at MIT by a group of physicists with long experience in designing nuclear weaponry, whose familiarity with science education was almost exclusively in training professional research scientists.

This emphasis of science curricula on “pure science” (removed from everyday experience) as opposed to practical science constitutes in effect a rigid tracking system in schools. The division between “academic” students who take chemistry in preparation for college, and those who take shop instead, is complete. The chemistry student does not learn how to harden a steel tool, and the shop student does not learn about crystal structure. In ways like this, the framework for extreme division of labor and perpetuation of the social class structure is built into schools. One result is that the future scientist is denied freedom as well as the mechanic. She is dependent on the existence of a class of workers to perform such tasks for her, and she learns quite early in school that this is the way things should be.

Of course, the number of women who become scientists is very small, as is the number of blacks, chicanos, puertorriquenos, indians, and other oppressed peoples. Aside form the obvious form of discrimination which places these minority children in schools that afford every impediment to learning, there are also the additional biases on the part of teachers themselves. Blacks, puertorriquenos, chicanos, and indians. for example, are often assumed not to have the intelligence or industry to become scientists; women are supposed to be too emotional for the rational processes of science. All these myths become self-fulfilling prophesies. These youngsters are not encouraged or helped to become scientists and so they don’t.

The prejudice against the children of the oppressed is revealed when teachers consider the student who performs well to be an anomaly—someone who is exceptional and unlike the others. Another form of prejudice is that against the use of non-standard English or cultural behavior patterns that are incompatible with the norms that the school system is geared to establish. Thus, although a child may have ability, teachers may discount it because they evaluate the child’s overt behavior as unsuited to an up and coming professional.

For women the discrimination begins with the opinions of teachers and counsellors that some vocations are “unfeminine”. Girls are thus channelled into secretarial or domestic skills or into the liberal arts, while the mechanical world is left to men. In this way most women grow up to confront an increasingly mechanized world with no real understanding of how machines work, the result being a helplessness which allows them to be dependent on and dominated by men.

For students who don’t pursue scientific studies, the curriculum is structured in such a way as to leave them feeling mystified, frustrated, and helpless against the enormous power of technology and those who control it. In many of the materials available there is a “hidden curriculum” which conveys the social myths that perpetuate the control of people through technology. For example, in “educational” films provided by oil companies, the telephone company, or NASA, scientists are portrayed as infallible experts. The message, though never spoken openly, is clear: the corporations and the military, through the enormous power of technology, are omnipotent. You are utterly dependent upon their benevolence. Scientists are high priests who work in closed and forbidden sanctuaries such as government and industrial laboratories. Their speech is ritualized, devoid of humor and meant to impress people with the awesome nature of their projects, such as sending a man to the moon. This is an old ritual that has been performed since at least the time of the pyramids. In all societies in which power has been concentrated in the hands of a very few, the rulers have round it useful to display their power through a high priesthood of “experts” who maintain their privileged position because they intimidate people with mystifying rites. And we are right to be frightened, because in this case the holy objects may be capable of destroying life on earth.

SOCIAL ASPECTS OF SCIENCE

One characteristic of most science curricula is their limitation to purely technical or descriptive material. Contrast this to most of science which is characterized by its important social ramifications. We are living in an age when the atomic bomb is already taken for granted, and science now raises the possibilities of genetic engineering, behavior control technology, complete automation of work, and universal tagging and manipulation of people. Yet these problems and the whole question of the use of science in our society are rarely broached as part of the standard science education. For people to have a real understanding of science and how it affects their lives, they must view it in its social context.

Over the last few years, in light of the Indochina war, the space program, and the emergence of environmental pollution problems, those who spoke of “pure” science have come to recognize that all science is tied in one way or another to applications. We now realize that here in America science and technology are developed to serve the profit and stability needs of corporate enterprise. Each year, for example, billions of dollars of government and industrial funding are spent on research and development. Research and development for what? To develop technology for health, housing, and transportation? On the contrary, this work is directed toward the development of more sophisticated weapons and counterinsurgency technology (to protect corporate economic interests abroad) and towards automation, information handling technology, and technologically-induced obsolescence (to maintain the viability of the economic system at home). The use of this technology results in death and destruction, in the waste of natural and human resources, in the fouling of the environment, and in the increased manipulation of society.

Control over science ultimately rests in the hands of a powerful ruling elite which directs American corporations, and in a government which functions in its behalf. Science and technology are used as tools for extending the present social and economic system: they have served to increase the wealth and power of the few at the expense of the many. In this context science can never be considered politically neutral.

The number of examples of how science has been used directly against people is limitless. In Southeast Asia infrared devices, computer monitoring systems, anti-personnel weapons, and biochemical warfare are used to crush every popular liberation movement. In the United States, a whole new catalogue of surveillance devices, riot control weapons, instant identification systems, data banks and other counterinsurgency technology are being used or are under development to suppress “dissidents.” who most often are people like us all. While these examples are perhaps obvious, we are beginning to realize the more subtle ways in which science is used to rationalize the social order. Take for example the use of social science to justify in “scientific” terms the oppression engendered by the class structure of our society—”scientists” like Herrnstein claiming that social standing is based on genetic differences and Jensen asserting that blacks are inherently inferior. These are rather grotesque instances of the generally more pervasive use of modern social science to “explain” social injustice.

Faced with the political character of science, the least we can do as science teachers is to help clarify these social relationships. To accomplish this task requires not only that we make available to students information on how science is used, but that we also foster and help students develop what critical attitude which characterizes real science. We must help to expose the scientific and human irrationality of a system which reduces people to objects, which consumes their human and natural resources in fits of ecocidal insanity, and which pits people against one another when all could prosper.

TOWARDS AN ALTERNATIVE

What we realized finally is that as science teachers we are caught in a double bind: not only are we part of an educational system which functions to socialize people into the society, but in addition, we are part of the scientific and technological complex which serves to maintain the existing distribution of economic and political power. This situation makes it difficult to pose alternatives to our present teaching practice. On the broadest level, if educational and scientific institutions did not serve these purposes, they would not be supported. In the same fashion, if we as teachers don’t serve such purposes, we too would not be supported! Or to put it differently, we are highly constrained in our schools by the material we must teach (often packaged curricula) and the format in which we must teach it. How much liberty do we have, for instance, to not give tests, to not award grades, to not teach the required curriculum? All these structural features are part of what education is all about-especially in large schools or school systems with a sizeable bureaucracy. The fact of the matter is that we teachers have relatively little freedom to do what we and our students might decide is most desirable. After all, we do not control the appropriation of educational resources.

We are left with the frustration and exasperation of unwittingly or unwantingly contributing to the maintenance of authoritarian structures, social class divisions, elitism, mystification, powerlessness, and alienation of people from science. But we know that science and technology could provide the tools for people’s liberation. We can envision a society in which science teaching would help free people from want and help provide the know-how which would enable people to reach the fullest of their human potential. But that is a very different society from the one in which we live. It is a society that won’t just happen. We must work to make it happen.

Our role as science teachers in that struggle for change has many facets. First we can help people master the technological world around us. To a large extent people’s feelings of powerlessness stern from the fact that they don’t know how to do things for themselves. Their ignorance forces them to rely upon others, upon the experts who Know. But people can learn how to eat good foods and how to take care of their bodies so they remain healthy and don’t rely upon doctors. Women can learn to do their own pregnancy testing. Students can learn the facts about drugs. People can learn how their automobiles and refrigerators work so they don’t rely upon repairmen. The importance of self-reliance has been brought home to us by the legendary resourcefulness and ingenuity of the Vietnamese people in the fact of American aggression. Their strength is a measure of their confidence in themselves.

Second, as science teachers we can make it our practice always to raise amongst our students the social aspects of scientific studies. How empty, for example, is the discussion of ecology without discussing the politics and economics of consumption and waste? How can we mention transistors and computers without discussing the national data bank and the automated battlefield? What is the meaning of cell biology and genetics without talking about the health care delivery system, ethnic weapons, genetic manipulation and sickle cell anemia? Of what significance is the subject of energy without a discussion of electrical power demands, pollution and radioactive waste disposal? How can the study of human anatomy ignore the questions of contraception, abortion, and the discrimination in many forms against women? How can mechanics and machines be considered independently of automation and the alienation of people in advanced industrial society? How can chemistry be taught without reference to the activities of oil companies in the third world, the marketing practices of the pharmaceutical drug industry, and the variety of chemical additives appearing in our foods?

Third, we can seek to expose the hidden curricula in our methods and to uncover the ideological and political premises of the materials we have used in our teaching. Students can be tremendously helpful in cutting through ideological bullshit. But in addition to such critiques, which increase our understanding of our role as teacher, it is important to gather and prepare new materials to use as a substitute for those in present use. There is now a substantial alternative collection of written materials and films dealing with education and problems of technology which science teachers will find useful. (See the bibliography which is interspersed throughout the teaching section.)

The alternative, then, in science teaching lies, for the present in our practice-in how we teach, in what we teach, in how we relate to our students, our fellow teachers, and to everyone else, of course, Let there be no illusion: fundamentally changing the way science is taught in our schools and used in our society is only possible as part of a fundamental change in its political and economic structures. This won’t occur without a struggle. But as teachers, we can be exemplary in our practice, in our critical attitudes, in our democratic spirit, and in encouraging others to their fullest abilities. We can work with students and scientists as part of a national and local organizing effort to share materials and work together, to make science and the schools serve the people.

CURRENT PROJECTS

This past year we in the SESPA Science Teaching Group have initiated several projects with the help of contributing to the effort to develop real alternative in science education. We will briefly describe these projects here in this pamphlet to give you an idea of their flavor, but more information is readily available.

Two of the teachers in our group have been using the recently developed hip biology curriculum Ideas and Investigations in Science (IIS). In the last several months we have been analyzing this curriculum, its effectiveness as a teaching tool and the social and political messages conveyed by it. Despite many new and positive features in IIS, this curriculum still fosters the same cultural values and ideology found in older teaching materials. The scientist is presented as the usual stereotyped infallible expert. Social issues are introduced in the curriculum, but usually with a very heavy bias toward the values of the dominant class. The usual sexism which permeates our present educational system is also present here. Finally the curriculum was designed for slow learners and the unmotivated, it thus serves as another tool to facilitate the tracking of students. We are seeking ways to use the positive features of the curriculum in conjunction with our own resources and questions to confront problems we have raised earlier in this pamphlet.

Along much the same line, several teachers in our group have been analyzing the Project Physics course material. We have selected this particular curriculum because it, more than any other, attempts to deal with social and cultural aspects of physics. The emphasis, however, seems to be that the most important cultural phenomena associated with science are the lives and work of the great scientists, and their interaction with literary, artistic, and philosophical currents. This emphasis unfortunately stresses the elite intellectual traditions of science rather than its important social and productive functions in western society. To date most of our work has been done on analyzing the assembling alternate materials for Unit 3: “The Triumph of Mechanics.” We hope to eventually cover all the units.

One exciting project has centered around the controversy over the Herrnstein IQ article which appeared this fall in Atlantic magazine. Teachers in our group have asked students to read this article and have then video-taped the classroom discussion. These tapes indicate that students can often see through the mask of science and get to the heart of what is really being said. In this case Herrnstein’s racism was clearly exposed. But the tapes also reveal Some of the attitudes and prejudices of the students with respect to science and scientists. We hope people will take the opportunity to see these tapes.

Resource material other than the textbooks currently in use is essential to teach the social and political implications of science. Such alternative teaching materials are presently available in the form of pamphlets such as The Earth Belongs to the People, which analyzes the ecological problem in a socio-economic context, magazines, audio-visual aides, and paperback books. Although a list has been gathered for this issue, we still need your comments and additions to the material, and soon an annotated version may be compiled. We would appreciate your help in our search for alternative resources. Should you know of material you think would be helpful, please write to us. Another important, and as yet unused resource, is the “people resource.” In order to demystify the scientist to the students, a list of people actively engaged in research who are willing to speak with students in the Boston area, or have them visit their labs, is being compiled. The task of gathering new information is large, but without the availability of new resources, the dogma of the past will only continue.

More detailed reports of the IIS and Project Physics curriculum studies are available through the Boston chapter office. We hope that people will continue to send ideas and materials here, so that we can eventually compile a more complete booklet on all aspects of radical science teaching. By working together and struggling together now we will form the bonds for the future.

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 5 <<