This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Up Against the NSTA

by Dan Connell

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 4, No. 5, September 1972, p. 11 – 15 & 26

April 1972. New York City. The annual National Science Teachers Association convention. Science for the People was there again, our second organized action, this year as official participants in the program (see Science for the People, July 1971 vol. III No. 3, for a discussion of our actions at the 1971 convention in Washington, D.C.) We were better organized this year, with more people, many of whom had been working together now for a year, with a more appropriate selection of literature and materials, and with a clearer sense of who we were dealing with based on our previous experience. On the other hand, NSTA was also better prepared for us with the convention topic, ostensibly the relevance of science—”Alternative To Science or Alternative In Science?”—and with us as part of their program.

As a result of these and other factors our approach and impact were different in many ways from last year. Our shock value—the impact we had simply by virtue of being a “radical” group—was less. They knew us by now. But this also helped us to avoid being merely a spectacle, a side-show attracting only the curious and the bored. Those who came to us came to deal with substantive questions in a way that was less possible last year. Though we saw fewer people in our workshops and planning sessions, we were able to stimulate the formation of an SFP chapter among New York teachers and scientists.

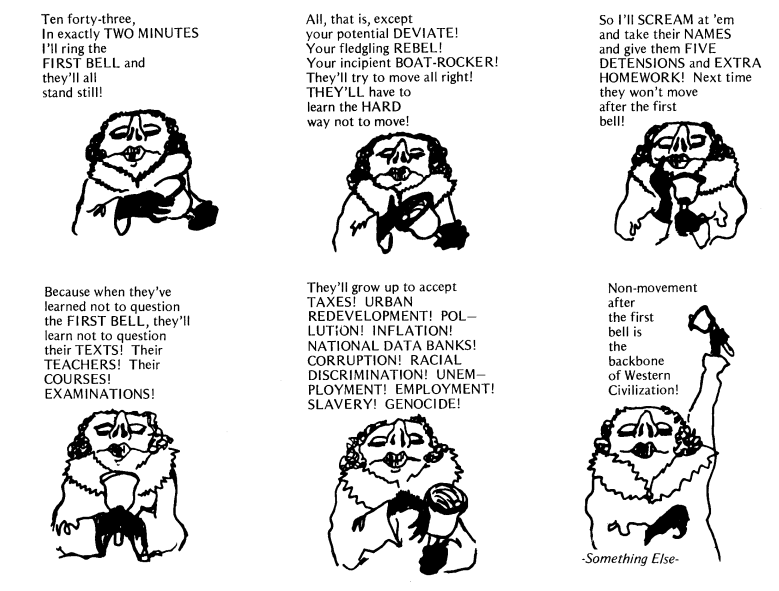

Two major themes ran through all of our activities. First, we tried to communicate our analysis of the social and political implications of science teaching. We wanted to demonstrate that present science curricula and teaching materials are heavily weighted with a hidden curriculum which helps to prepetuate the cultural and political values of the class which dominates this society. Further, we wanted to discuss with teachers the need for integration of political and economic factors in science teaching. Second, we used all possible opportunities to illustrate the destructive nature of the usual authoritarian classroom structure which corresponds to the apparatus of oppression in this society, in general.

There were some immediate results of our efforts at the convention, and there were weaknesses and failures which we have tried to analyze collectively to avoid next year at NSTA and in other organizing. By presenting this article on our actions in SFP we hope to stimulate others to criticize and inform us also. It is important that there be more dialogue within the revolutionary movement and within the pages of SFP on how to increase the number of scientific workers participating in radical political activities. We hope the recap of our experiences will contribute to that dialogue.

GETTING READY

Last spring, following the NSTA convention, the Boston Science Teaching group held an area wide meeting to tell local teachers what had happened and to begin organizing continuing projects. The results was little more than a mailing list. Concurrently we arranged with NSTA officials to have three of our members on panels at this year’s convention, to have a room for films and workshops throughout the convention, and to be listed in the program.

In the fall we tried again with a large meeting and fared better. Based on our mailing list and on word-of-mouth contacts we re-formed and broke up into task-oriented groups. It became obvious to us that to maintain people’s involvement, theory had to be manifestly connected to practice. Teachers who are overburdened with extra duties, lesson preparation, and frustration with their jobs will simply not find the time for political activity unless it feeds back directly into their work. Not surprisingly, those groups which dealt with curriculum analysis and development–for example, IIS Biology and the Herrnstein IQ study groups—generated the most enthusiasm and the most concrete results.

However, we also became sensitive to the danger of becoming national producers of alternate curricula competing with but not confronting the established producers. It therefore seems to us necessary to concentrate on encouraging teachers to see the need for analysing curricula and to give them the means to do their own critiques. Further that the most valuable work they can do is to pass this on to their students and to have them do the analysis. In this way we do not make the error of handing down our views to the students, but rather give to them the power and the motivation to arrive at their own conclusions.

In this context, we found both in the fall and at the convention, that conventional materials can often be more effective than radical ones in generating a radical critique; that is, to expose the racism, sexism, and exploitation manifest in “traditional” texts and films can be the best means of beginning a broad social and political analysis. A major effort to create new curricula could be enormously time-consuming and of questionable effectiveness. On the other hand, we can offer workshops on making these critiques and occasionally develop our own materials on particular issues.

In addition to the need to merge theory with practice, we grew to see the need to merge our political lives with our social and personal lives. Many of our meetings began over dinner and ended with wine or grass. Interspersed through our political discussions was talk of our jobs and our home lives. Many of us have become close friends and see each other often outside of scheduled meetings. We think these interpersonal connections enhance our political effectiveness as a group and will ensure our continuing work together. It has also helped us to see in practice that shit-work need not be alienating if the conditions under which it’s done and the ends which it serves coincide with our collective needs.

In January, a sub-group formed to coordinate preparations for NSTA. We met weekly to draw up plans to attend specific sessions; to gather literature, films, and equipment; to rewrite our introductory pamphlet; and to develop tactics. We discussed guerilla theater, none of which was actually used, though we still think it offers interesting possibilities. Individuals were assigned responsibility for various sessions and reports were made on issues we hoped to raise and tactics we intended to use. Tasks at the convention, such as mimeographing leaflets, peopling literature tables, staffing our activities center, scrounging equipment, and so on were also assigned. And we tried to coordinate our preparations with groups at Stony Brook, Cornell, and NYC who planned to join us. To avoid the confusion and last-minute scrouging of the previous year, we determined to be well-prepared. It turned out that we weren’t nearly as organized as we could have been, but more on that later.

SFP IN NYC

Finally on April 6th and 7th, we in Boston headed en masse to New York’s plush Americana Hotel where we met some of our brothers and sisters from Ithaca, Stony Brook, and Washington who came also to be part of the SFP actions. We started out as a relatively diverse group, but in the course of our actions coalesced and grew together. And as we grew together so in tum did the actions. In fact the interactions of the SFP activities with the regular NSTA events had an exciting dynamic to it—our actions beginning calmly but slowly building to a climax after a couple of days. The most distinguishing feature over all of the SFP activities was their wide diversity (made possible by the number of our people) ranging from literature tables, to film workshops, to heavy rap sessions, to a strong presence at regular sessions, to outright disruptions, to well, you name it.

For example in the opening days of the meeting, we distributed close to 4,000 copies of our pamphlet Science Teaching Towards an Alternative, which many people found interesting and provocative as well as explaining what SFP and the Science Teaching Group are all about. Nearly 1,000 copies of smaller leaflets on the hidden curriculum in a high school biology (IIS) and physics (Project Physics) curriculum were also distributed. NSTA had “kindly” given us a suite to keep as a base for our activities. We had on display there a large collection of alternate literature (much of it for distribution); but we also had literature tables set up at various other locations in the two hotels. Despite the fact that the room turned out to be so far away from the central convention as to be almost unfindable, and despite the fact that our tables were occasionally hassled and shut down, we still managed to attract a lot of seriously interested people. In fact, we sold much more literature than anticipated, essentially selling out the woman’s pamphlet, Our Bodies, Ourselves; a pamphlet on Heroin and Imperialism entitled The Opium Trail; and a radical ecology analysis, The Earth Belongs to the People. And in our suite which was also used for films, workshops, and rap sessions we showed over the course of the convention the NARMIC slide/tape on the electronic battlefield; a film version of The Earth Belongs to the People; The Mystery of Life, a really heavy CBS documentary on genetics; a film on the military-industrial complex; The Opium Trail; and a videotape of a classroom discussion on the Herrnstein IQ article. All of these films and the literature have political and economic analysis inextricably tied up in the discussion of the scientific or technical material usually taught in a “neutral” way in the science classroom.

While some of us took turns staffing the suite and tables, others went to raise political issues at sessions and lectures. It was this type of action· which provoked the most controversy. At the first session on Friday morning, “Turning on the Educationally Uninvolved” by Harry Wong (designer of IIS Biology and proponent of the “Sesame Street approach” to curricula)—the Bob Hope of the teaching establishment—assured us that turning on uninvolved children is purely a problem of using the correct Madison Avenue techniques. Before he spoke we placed on the chairs copies of our IIS critique and a leaflet entitled Turning Them On To What? which people read as they came in, assuming them to be connected with the performance. Although our leaflet reached a lot of people, the very mild tone of our presence didn’t stimulate much interest. We realized afterward that we should have been prepared to confront him more actively, possibly with guerrilla theater, but at least with verbal challenges from the floor.

In the afternoon one of our people gave a presentation on open education, and in the evening, we held an open house in our suite where we talked in small groups about our program and plans for the convention. By mid-evening, the open house became a planning session for the next day’s activities. The Boston group went over its plans to attend specific sessions but there was some disagreement over the use of confrontation tactics, with the group failing to reach consensus. At this point the Science for the People contingent had swelled to thirty members from Boston, Stony Brook, Washington, Cornell, New York, and Detroit. One of the New York group was a media freak, and brought his videotape apparatus with him. He stayed with us for the whole convention, taping our discussions, actions and sessions and the response of people at the convention to our activities. He showed these tapes on a monitor at our literature table and in our suite, generating a good deal of interest and helping us to evaluate our performance. The presence of the camera at sessions also tended to act as a restraining force on our most vocal opposition.

Early Saturday morning the first of the confrontations occured. At a session sponsored by Union Carbide, two of us attempted to display placards questioning the company’s war-related work. The placards were taken from us and we were forcibly ejected from the meeting. A subsequent argument with an NSTA official developed in which he petulantly demanded to know why we were acting this way when we had what we wanted (our own room off on the fifth floor); but the incident was dropped when we left the area. Meanwhile, we had run off over 4,500 leaflets announcing the SFP workshops on the NSTA photocopy machine when it burned out leaving us (and everyone else) with no further means to make up leaflets or notices.

In the afternoon tension between us and the NSTA increased through several other incidents. One of our literature tables was closed down at the Sheraton and a disruption took place at a session on lasers. When several SFP people tried to raise questions about military uses of lasers and the politics of technology, they were shouted down and threatened with arrest.

Simultaneously, however, others were attending sessions on genetics, drugs, and community/school relations. At the last, one of our people was on the panel. Through a preliminary conference the panel agreed to give short talks and then to move to the floor for an open discussion which lasted three hours and moved from typical questions on schools to broad questions of the possibilities of change in a capitalist bureaucracy. In the other sessions, more muted approaches were used—questions were asked and pamphlets were distributed.

That evening we had another open meeting to evaluate the day’s activities (events) and plan for Sunday. It was clear that the NSTA viewed problems in schools as failures of technique. Their interest was to arm teachers with an arsenal of gadgetry and props in order to circumvent potentially threatening losses of control and motivation of the students. It was by now becoming clearer to us that our task was to expose the bankruptcy of this approach and to persuade teachers to join us in opposing it and in developing alternative approaches. The principal organizing tools which we had were issues we brought into the convention and the structure of the convention itself. If we could establish our points with reference to the NSTA meeting, it remained only to connect the way the convention was run with what happens in the schools.

The question of the appropriate tactics was raised once again. There were those who felt that disruptions alienated potential allies, and there were others who felt that passive acceptance of the forms of the convention contradicted our basic position. It was suggested that some of us were more concerned with being correct than with being effective, and it became clearer that tactics were not independent of concrete situations. If, for example, we had tried to force a restructuring of the afternoon’s school/community session (as we had planned), the three-hour discussion could not have taken place. On the other hand, in sessions where we had tried to cooperate and ask questions only in the assigned time, the issues were often ignored or dismissed as out of hand.

With Sunday morning came perhaps the most choatic confrontation with the NSTA leaders, one which illustrated the contradiction between NSTA rhetoric and NSTA practice. It occurred at the “open forum” of the NSTA Issues Committee, billed as an NSTA Listens session. Last year this session had been our most fruitful action and we were not to be disappointed this time either. Prior to the meeting we rearranged the chairs into a circle with the enthusiastic help of the NSTA members who had come early. But when Morris Lerner—president of NSTA—came in, he freaked out, ordered the chairs put back, suggested those without badges (only us) should leave, and ruled that only written issues could be discussed. Undaunted, we quickly wrote up resolutions on the war, tracking and sexism, and a demand for open-structure of all NSTA sessions.

But these were then swept under the rug by Lerner, who tried to concentrate on the resolutions he and his clique had prepared on federal subsidies for curriculum development and other non-controversial topics. Having decided that he alone was responsible for determining which issues were worth discussion, he ruled that resolutions on the war and tracking did not merit consideration. The many questions from the floor about the authoritarian structure of this “Open Forum”(!) were ruled out of order. However, the audience didn’t permit him to get away with this. In fact it was one of the persons in our group who had been opposed to disruption the previous evening who stood up and most eloquently exposed the repression that Lerner was attempting to impose. This attempt to manipulate the meeting backfired as most of the audience rejected the closed nature of the open forum. The disruption of this meeting (and it was thoroughly disrupted) was particularly effective because the other side was forced to precipitate it, and the audience itself participated in it.

By coincidence SESPA was officially scheduled to hold a panel on curriculum alternatives at the hour when the issues meeting broke down and was adjourned. We invited everyone to attend and over a hundred people came, including not only sympathizers but also several who sought revenge by disrupting our meeting. They immediately asked who the chair was in order to focus their attack and in a brilliant tactical move one of our people proposed a rotating chair and called on one of our attackers first. Finding himself in temporary control of the meeting, his anger diffused and he initiated a discussion on democratizing meetings. As the meeting developed, we talked about racism, economics, power, the war—all the issues we had hoped to raise earlier. Where the disruption of the first meeting had raised questions, our follow-up meeting focused those questions on basic political answers.

The day’s activity was rounded out by three more sessions which deserve mention before some final criticisms and observations. Sunday afternoon there was a second confrontation at the laser session (a series of three) as SFP people again raised questions of the political aspects of laser development and use. Several SFP people were ejected by hotel security guards. By contrast, a session on “Teaching the social implication of science in the classroom” was turned voluntarily into a discussion group. This panel which was billed as “science teachers talking about their classroom experiences,” turned out to consist of three academics (!), including one SFP person. With the agreement of the chairman, two of the panelists limited their presentations to a few minutes and opened up the discussion to teachers in the audience. After this was over, teachers thanked us for saving what otherwise would have been a deadly session. And last, on Sunday evening Barry Commoner, speaking in tails at a $12 a plate dinner, talked to a General Session about the social and political implications of science teaching. He said that science can’t be taught without politics and economics can’t be taught without mentioning Vietnam. That was our line! He got a standing ovation, while the hotel managers were outside threatening to shut down our literature table! Enough said!

AFTER-THOUGHTS

What did our presence at this year’s NSTA convention achieve? Nearly all of us left New York with the feeling that we had made a significant impact on the teachers and on NSTA itself. In fact, raising the issue of open structure meeting has resulted in NSTA leadership indicating that the format of a good many of next year’s session will be changed. However, perhaps the most important result of our actions there was the formation of a New York City Science for the People chapter which will deal with issues of science teaching. In addition to a few people from NYC who worked with us from the beginning, a much larger number had contact with us over the several days we were thre. Finally, on Sunday about ten people got together in our suite and decided to start a NYC group. Comprised of scientists, engineers, nurses and science teachers, they have had several meetings since the convention. In addition to NYC contacts, we also met a number of others who were interested in keeping in touch with us. One of the teachers works in Detroit and is already in contact with us in order to organize for next year’s convention which will be held in that city.

We believe that the materials we brought with us contributed in an important way to raising consciousness among teachers. The surprisingly large sale of pamphlets with radical analyses described earlier should have enough effect in itself to have made the trip to NSTA worth it. Although, because of our location, we did not attract large numbers of people to our film-workshops, the few times we did have 30-40 people there, we engaged in valuable discussions following the films.

A number of teachers told us that is was a relief and pleasant surprise to get away from the rigidly organized speaker (panel) audience structure of essentially all the sessions at the convention to our open, free-wheeling and collectively directed workshops. In planning for NSTA, we had not considered this as a main issue to be brought out at the convention, but teachers there quickly made it clear to us that this was a major concern. What really appeared ironic was the widespread liberal discussion of open classroom structure in the schools which did not have any impact on the structure of the meeting itself.

IIS: HIP TEACHING OF THE HIDDEN CURRICULUMOriginally prepared for and distributed at the NSTA activities in New York, the booklet criticizes the IIS (Ideas and Investigations in Science, Prentice Hall, 1971) curriculum. Although it deals with the “relevant” issues and has succeeded in capturing the interest of students, it exhibits a hidden curriculum which has not changed with the innovations in techniques and material. It holds up the astronauts as heroes and “militants” as people to be stood up to. It refers to “success” and “the establishment” in ways which set up the acceptable models for students to strive for. For the full critique, write to Science Teaching Study Group |

The most serious questions about our success at the convention arise from a discussion of tactics. It is clear that we were not united on the more “extreme” examples of disruption. On the one hand our intervention in the laser session forced the speaker to confront the issues of the military uses of lasers. He eventually, without further prodding began to bring this out himself. The heat generated by our activities there significantly raised our visibility at the convention. People who had heard of our actions, but had not been there, came to talk with us. After these sessions several of our people became engaged in long discussions with teachers who had heard the laser talks. However, it is also clear that we antagonized a good number of teachers who had come to learn something about lasers. We might have avoided this by being better prepared, for example, with a leaflet or statement explaining our actions.

It would seem that confrontation, restructuring, or issues by themselves are not enough to change peoples’ attitudes. One key factor is to what degree the people are involved in any of these tactics. We should be particularly aware of the concrete conditions within which we act and of the mood, attitudes, and receptivity of the people whom we hope to affect. There is a tendency among some radical groups to smugly hold themselves above the people and act “for” them against whatever power structure is at hand. Whether we are dealing with science teachers, scientists, workers, or students, we have first to identify ourselves with them and their interests before we can move with them toward real change. As postscript, it should also be added that preparation within the group is also essential. We were weaker here than we had thought in several areas. First our political discussions had not been thorough enough—we might have been able to arrive in New York with less division on the question of tactics. Second, we did not have enough basic information on speakers and sessions and we had not planned our actions (and alternatives) well enough. And finally, we were short of equipment. We should have had our own mimeo machine, typewriters, and projectors. This was an inexcusable oversight and we paid by not being able to leaflet at all on Sunday after the NSTA machine burned out.

That’s all of it. We welcome criticism and suggestions either in a future issue of SFP or directly to us. Our group, the NYC group, and a Detroit group are now preparing plans for next year’s convention in Detroit and working on a variety of other projects. Inquiries should be sent to Boston Science Teaching Group, c/o Science for the People, 9 Walden Street, Jamaica Plain, Mass. Copies of the pamphlet printed in this issue and the advertised leaflets on the IIS Biology and Harvard Project Physics curricula are avaiable at this address.

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 5 <<