This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

AAAS Actions at Philadelphia: The Solidarity of the Long-Distance Activists

by Steve Cavrak, Britta Fischer, & Amy Salzman

‘Science for the People’, Vol. 4, No. 2, March 1972, p. 4 – 10

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is the largest organization of scientists in the country and includes many member societies of different disciplines. Its weekly magazine Science has some 150,000 subscribers.

For the past three years Science for the People has held actions at the annual AAAS meetings1, questioning the political manner in which science priorities are established and the hierarchical and elitist way in which science is organized.

The AAAS finds itself in a curious (maybe not so curious) position in the face of these actions taken by fellow scientists. The Association tries to maintain the myth that science is pure and neutral, yet it is highly political: it attempts to influence the government’s science policy. Just how political these meetings are is evidenced by the fact that politicians like Hubert Humphrey, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and William Bundy are featured speakers. Yet at the same time Moynihan, fearful of political discussion, cancelled his vice-presidential address saying that politics has no place in science. What is apparent is that theories that justify and thus help to maintain the status quo are considered to be social science—legitimate topics at the AAAS, whereas the questioning of these theories, as encouraged by Science for the People, is branded disruptive and irrational.

The session Technology and the Humanization of Work typified the AAAS’ handling of important questions and Science for the People’s challenge. The format for this session was the usual: panel/silent audience/questions later. You walk in and, unless you are one of the few panelists, sit down in the neatly regimented rectangle of seats that make you unable to face anyone but the people on the podium. There is no microphone you can get to. In fact, according to the rules of this session, you are supposed to keep your mouth shut until ten hours from now, when there will be a special informal question-and- answer session.

The panel consisted of plant managers, company vice-presidents, industrial relations consultants, and university professors—people who were totally sheltered from the conditions about which they were holding forth. No secretaries, no assembly-line workers, no farm-workers—no one who had experienced the dehumanization of work firsthand. The same was true for the audience. When we pointed out this deficiency [see insert], the managers said that the meeting was open to the public (at a cost of $15) and notices had been sent to factories in the Philadelphia area inviting workers to come; of course, none of the company executives had thought of giving some of their employees a paid day off and an expense account to help them attend the meeting.

|

LEAFLET HANDED OUT AT ONE AAAS SESSION You are about to attend a session on Technology and the Humanization of Work. Yet, though there are technologists and managers on the panel, there are no workers (there is an union official). That a panel should exclude rank and file workers is itself indicative of the basic problem. For technologists do not confer with the object of their experiments, nor do managers confer with the machines in their plants—and for these persons, that is just what workers are, objects. There can be no meaningful discussions of the humanization of work that does not begin with an explanation of the root of the problem—an economic system that treats labor as a commodity and creates or improves technology for the maximization of profit. In fact, what does it mean to speak of the humanization of work in a system where the workers themselves are reduced to mere objects, bought, sold and traded like all other goods according to the demands of capital, not according to human considerations? For the workers, their creativity, humanity, and desire to be socially productive are drowned in the competitive struggle for economic security. They do not control the conditions of work nor the use made of the products of their labor. The basic assumption underlying this symposium is that workers will remain a commodity. The effect of a session such as this is therefore not the humanization of work but the use of more sophisticated technologies and devices for controlling and manipulating workers in order to “maximize production and improve labor relations.” The function of such studies is to attempt to make commodities feel like human beings and in so doing to prevent antagonism to an economic-political system which perpetuates the dehumanization of work by its institutionalization of labor as a commodity. However, no one should think that the dehumanization and alienation so evident in the daily activity of production personnel and lower echelon white-collar workers is limited to these groups. The managers of the corporation or organization which harnesses human labor for the purposes of profit apparently have greater control over their own lives and work. Though they consciously exercise power, they are both objectively and subjectively dehumanized by their roles. Their job is to manipulate other human beings, to treat them as commodities, as things. Thus the managers’ relatively increased freedom has been bought at the expense of the freedom of others. There is only one human species—the exploitation of one human by another dehumanizes both. What will be critical to the actual humanization of work, is not only a fundamental analysis of the present forms of institutionalized dehumanization but action to change these institutions; workers’ control of their work and of their lives is essential. Managers and industrial-relations technocrats serve only a destructive function. The proper topic for this session would be strategies for gaining workers’ control and elimination of the managerial positions and technocratic functions of the present panelists. SCIENCE FOR THE PEOPLE! |

The Great Authorities spoke. Everything they said (or omitted) reflected the fact that their concern is for the corporations and their profits and not for the people who are being dehumanized by their working conditions. The manager of the pet foods division of General Foods said that “workers have to relate to their product.” He didn’t say that what workers really produce are profits—profits for the owners and managers of their companies—and that maybe workers should relate a little bit more to the profits.

Then a speaker who had devised a plan to redefine the work of the telephone companies’ “customer service representative” (the person you talk to when you want to get a phone installed or to complain about bad service) addressed the group. He kept referring to the service rep as “she.” Finally someone interrupted him, “What do you mean by ‘she’?!” “Well, there are also some men in that job,” he replied, and went on. A few minutes later the same thing happened. But finally, he pulled out a chart with cartoon figures on it—the figures of a “manager,” a “supervisor,” and a “service rep.” At no surprise to us, the manager was clearly male while the other two were clearly female. That did it.

“I want to know just exactly what percentage of women are employed as workers and what percentage as managers!” Pandemonium. Someone tried to put his hand over the mouth of the person who asked the question. The chairman was shouting about disruption and the chance to ask questions later. Some of us were demanding an answer to the question. The speaker was trying to say something. Finally things quieted down and the speaker was just about to go on when a straight scientist attending the session said quietly but firmly, “I should like to hear the answer to the question,” and someone else said, “I want to also,” and half a dozen more spoke up, and the session was ours. The chairman was forced to realize that the audience was more responsive to us than to his heavy-handed attempts to run the meeting. Now the questions really came. The percentage of women workers was some 90%, but the percentage of women managers was almost nothing. Yes, he replied, this probably did reveal a degree of sex discrimination. Was there anything in his plans to humanize work that would eliminate this discrimination? No there really wasn’t. How was it possible to humanize work without humanizing the fundamental human relationships at the place of work? He tried to explain how we couldn’t do everything. Was the telephone company really interested in providing better jobs for people or was it more interested in getting as much work as possible out of the people on the job? He said that it was probably the latter.

Just before the meeting adjourned, several panelists thanked us for coming to the session, remarking that contrary to their first impressions, our participation was both sincere and constructive.

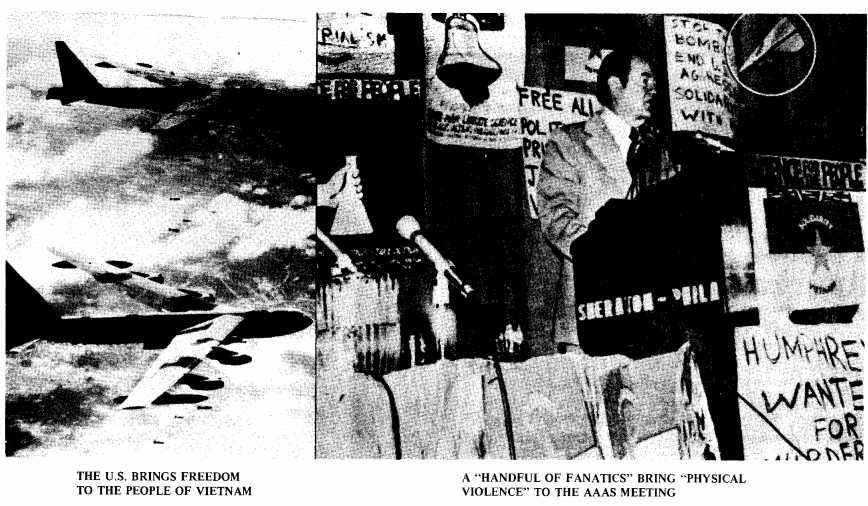

On the fifth day of the conference William Bundy, Undersecretary of State under Johnson and chief architect of the air war, was scheduled to speak on “Conflict Situations: Vietnam—The Knowledge Gap.” After years of the war, voluminous documentation of government lies and the overwhelming anti-war sentiment of the people of the. United States, what greater insult to the audience could be devised than having government ideologues read prepared papers on this subject? We couldn’t and didn’t let it happen. At 8 a.m., an hour before the meeting, after all-night discussions and preparation of tactics and questions, we arranged the chairs in concentric circles to break through the usual schoolroom atmosphere. The panelists could no longer be segregated from the audience and the microphone was now available to all. Leaflets with questions were on everybody’s seat. Bundy answered the questions glibly and called for more research on whether there really was massive bombing of civilians in North Vietnam. It seemed for a moment that the dull bureaucratic style of his answers might color the entire meeting. However, the audience felt otherwise. Once begun, the questions couldn’t be stopped, not by the chairman, who was forced by the audience to call a vote on whether we should return to the prepared speeches and then have a discussion, or have an hour of discussion and then speeches. The vote for the latter went 73 to 56. (The option of having discussion only was unfortunately lost in the shuffle.) Now the questions really came down: What kind of system is it that produces men who willingly fill the roles that compel them to devise and justify destruction of millions of people? He never answered that one. Upon proposing that a citizen’s commission investigate all the facts concerning the war he was asked how such a commission could do the job if he, Bundy, who was at the center of decision making, could not come up with the facts. His whole cynical game of sometimes claiming expertise and at other times ignorance—whichever suited him better—was exposed. At one time he referred to the government lies as unfortunate mistakes, at another time he countered a question on people’s anti-war sentiment by saying that the will of the people is vested in Congress and Congress continues to vote appropriations for the war. He was caught in his own lies when someone with a great deal of detailed knowledge who had been to North Vietnam countered Bundy’s false assertions about the role of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG). At one point Leslie Gelb, a Pentagon Paper writer now turned against the war, accused young people of not appreciating how difficult it is for people educated in the ‘forties and ‘fifties to change their views. He was answered by a woman in her late twenties, who emphasized that most of us had gone through the same Cold War brainwashing, that our awareness of the inhumanity of the system did not grow in a vacuum but was preceded by the same kind of indoctrination Gelb had received.

After two hours the chairman chose to hustle Bundy out of the room when the audience showed more interest in having him continue to answer questions rather than give the prepared talk. The discussion continued for another hour—without them.

Such a thorough restructuring of the session was not as easy as the final success might seem to indicate. We needed a program that would be acceptable to and involve the rest of the audience. We had to work out tactics with political content. We needed enough understanding of the dynamics of the situation in order to be flexible in our tactics. This required a sense of community and mutual political understanding that we could not have on the first day, when we had just gotten together from all different parts of the country and didn’t know one another. Instant consensus was not possible. We had to work out questions such as what constitutes freedom of speech, whom we wanted to reach, how we should relate to the media, and whether people who had participated in the decision making process had a responsibility to carry out decisions of the group. Initially, not all of us were aware that these problems existed. Thus the planning for the first major event—Humphrey’s speech—was inadequate and led to a poorly coordinated action. As the week progressed, our sense of community grew, our political analysis became clearer, and, as a result, the actions were more coordinated and effective.

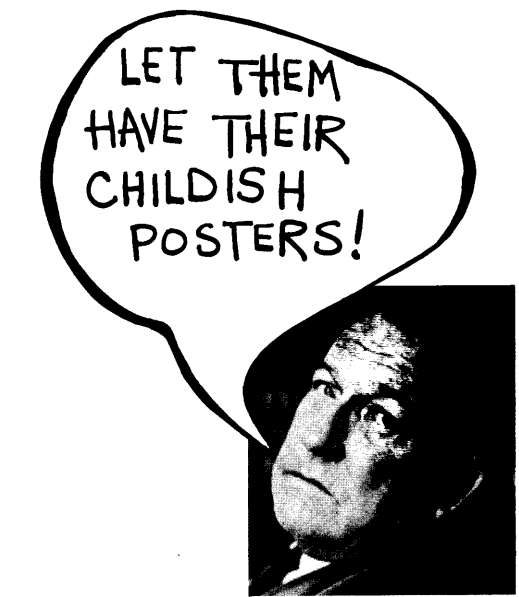

Half an hour before Humphrey was scheduled to speak the entire stage was already decorated. People—most of them from the several participating groups—had put up Science for the People posters, Vietnam solidarity flags, and several hand-lettered signs with slogans such as “300 more killed today.” The posters remained. The AAAS leadership, wanting to avoid a confrontation on this occasion as on others, piquedly claimed that the critics should not be taken seriously. “Let them have their childish posters!” said outgoing AAAS President Athelston Spillhaus. Thus Humphrey made his promises for a peaceful future and his pleas to forget the past underneath a placard reading “Humphrey, Pimp for U.S. Imperialism” and amidst a shower of paper airplanes made from NLF flags—a timely reminder of the new escalation of the air war in Vietnam. Margaret Mead, upset over the remote possibility that the former Vice President might have .been hurt, said to some of us later, “the paper planes could have hit him in the eye.” When we reminded her about the real bomb-laden U.S. planes over Vietnam, she retorted, “That’s not the point.” Apparently not everyone understood the irony of bombarding a leading government spokesman with paper Vietnam airplanes.

Anyway, Humphrey gave one of those apologetic-sounding, politically opportunist speeches, punctuated occasionally by a comment from the audience: “Surprise!” rang out when he claimed that the true purpose of Project Camelot was not known to him in 1965, that at that time he and others believed it was an inoffensive social science research project. (Humphrey’s belated acknowledgement that DoD-sponsored Project Camelot was designed to use social science techniques for counterinsurgency in Latin America comes long after the true nature of Project Camelot was uncovered by others2.) Not all comments were verbal. During his startling revelations a tomato was thrown. Whether by design or technical failure, it struck the front of the podium and left Mr. Humphrey’s beige suit impeccable, press reports notwithstanding. The tomato thrower and one of the paper airplane architects were immediately hustled out by plainclothes members of the Philadelphia Police Civil Disobedience Squad. They were later released without charges.

At the end of the speech a few questions were allowed. Did he endorse the immediate and complete withdrawal of all American troops from Indochina and the withdrawal of all support from the Thieu regime? He answered positively. It would be naive to be anything but skeptical about the credibility of such a statement by a candidate for President in an election year. year.

During the course of the first few days, Vietnam Veterans Against the War were carrying out activities all over the country, including Philadelphia. Appearing at our planning meetings they requested support for a march on Wednesday. Originally on Wednesday we had wanted to confront Moynihan, Nixon’s former urban affairs advisor who had advocated “benign neglect” of impoverished Black Americans; but he copped out. Claiming outrage at Humphrey’s reception he cancelled his political talk claiming “the radicals are out to ‘politicize’ the science association.”3 Moynihan’s absurd behavior stimulated two positive results: his peers among the AAAS establishment chided him, acknowledging Science for the People’s constructive role, ” … science gets at the truth … by open discussion of differing points of view;”4 and we were able to concentrate our efforts on actions in solidarity with the Vietnam Veterans.

How to make sure all the conferees knew of the vigil and march? Because of the short time, the thousands of fellow scientists who had to be reached, and the lack of dramatic impact of leaflets alone, the planning meeting concluded that it was necessary to go in groups to each of the AAAS sessions and demand three to five minutes to present the Vietnam Veterans message. Two groups were formed of 12 to 15 people each—so-called “Flying Squads.” A format was agreed upon for coordinated entry and presentation of the message in each session; the object was to convey the sense of urgency, to be brief but forceful, but yet not alienate the session participants. Each group decided that it was important for everyone in the group to have a chance to address a session—just one of many examples of how the protesters tried to keep their practice in line with their principles. This was a deliberate (and successful) effort to avoid elitism, to avoid always being represented by a few articulate “heavies.”

The tactic proved successful. Generally the speaker, chairman, and audience consented to hear the announcement. Some audiences even applauded. Some chairmen (no chairwomen were noted) thanked the group for coming. However, not all were successful. One painful instance involved the session on the “Immunity and Immunopathology of Oral Soft Tissues.” We opened the door and found ourselves physically in the middle of a slide show on tooth decay. An unplanned-for contingency; moments later a dozen and a half’of us were stumbling around in the darkened room trying our best to leaflet quietly and locate the chairman. Members of the audience began yelling “Down in front!” and “Get them out of here!” The dentists managed to extract us forcibly from the room before we could do our song and dance.

Just before 11 o’clock, individuals from the “Flying Squad” went back to the sessions to follow up the announcement by encouraging members of the audience to join the vigil and march. About 250 scientists, students, veterans, and dozens of plainclothesmen gathered in front of the Sheraton Hotel for the vigil. The site was appropriate not only by reason of convenience but also because, as several posters pointed out, Sheraton Hotels are owned by I.T.&T., one of the principal war contractors responsible for the automated battlefield in Vietnam.

Veterans in the lead, the scientists marched through Philadelphia. The response of the sidewalk crowds was encouraging. Some people raised their fists in solidarity, several times Black sisters left the sidewalk to march with us, and when we passed through City Hall, about a dozen employees looking down from the second floor lobby saluted the march with raised clenched fists.

At Independence Hall the vets and some radical scientists addressed the crowd. The vets told about other Veterans’ actions: the take-over of the Saigon Consulate in San Francisco and the take-over of the LBJ Library. The climax came when a veteran with the unlikely name of John Birch smashed a bag of his own blood on the steps of Independence Hall.

Heading back through the center of town to the Quaker Meeting House we heard someone yell “You’re a bunch of Commies!!” But the bogeyman of communism doesn’t work like it used to; from a half-dozen marchers the response was a loud “Right On!” At the meeting house, a Quaker greeted us from the steps requesting that those bearing arms not enter the house. Curiously, some well-dressed non-demonstrating men who had been with us the whole way and were actively photographing the whole group did not come in with us.

When we returned to the AAAS, some radical scientists went with the veterans to the larger, society-oriented sessions to try to raise bail money for their comrades who had been arrested at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Within five minutes, meeting attendees contributed $200. Clearly our “Flying Squad” tactic as well as the conduct of the vigil had not generated much hostility.

There were many other signs that the hostility of the Moynihans was not representative of the attitude of most of the scientists attending the Convention. The receptive and genuinely interested attitude people had toward us was most evident at our literature tables—our one continual activity. The lit tables were so prominent that many scientists spent twenty minutes going from table to table reading radical literature before realizing that they weren’t registering for the convention. At one end of the array of lit tables at the Sheraton was the Federation of American Scientists, the self-described “voice of science on Capitol Hill.” They hired a mode—a woman—to hand out their literature. At the other end was the Progressive Labor Party whose proclaimed purpose is “guiding [the people] to working-class revolution;” several soft-spoken academics sold their “revolutionary communist newspaper.”

Many scientists wanted to talk with us. Some told us they were glad we had come, we made it so much more interesting. Some were sympathetic with what we were doing, but didn’t understand or approve of our tactics. A few who had come to the convention as regular attendees ended up working with us full time!

For those of us who feared that people are so accustomed to receiving leaflets that they don’t even read them anymore; it was an inspiration to find that many people took anything we offered. It was impossible to create a leaflet glut! People would come up to our tables, receive three or four items, and stand there reading everything. Then came the discussions which were generally low-keyed and earnest. The scientists were friendly and sympathetic even if they disagreed. There was no red-bating. The many discussions with individual scientists showed that there was a genuine interest in our challenge to the scientific establishment. Scientists, perhaps more than any other professional group, have in recent years experienced that their privileges are not immune to the shifting economic and political winds. As the result of cutbacks of government funds in the space and defense industries and of the general slowing down of the economy, unemployment among scientists and engineers has reached much the same level as among other workers. These hardships or their threat have forced many scientists to take a critical look at other aspects of their work: fragmentation and meaninglessness of tasks, lack of control over the product of one’s labor, competition, the publish or perish rat race, the near-feudal control of graduate students by their professors. A profound uneasiness and ambivalence toward science is—often unconsciously—experienced by scientific workers at all levels. The efforts of Science for the People have been directed toward analyzing and struggling to change the social and economic conditions that give rise to this situation.

But the economic and social conditions that. have created unemployment and alienation among scientists and engineers are also the basis for the even more oppressive conditions of the working class, especially minority workers. It was with just such people—the hotel workers—that we first made contact. Since we had brought our stuff into the hotels through the back doors and had gone through the bowels of the building, we saw and made friends with many of the hotel staff. We couldn’t help noticing how busy they were kept wheeling around wagons full of iced water pitchers and flowers, all for the luxury of the distinguished members of the convention, who stood around chatting. Of course, most of the staff was Black, most of the scientists white. We talked with staff members, gave them literature, and for a day or two—until they were told not to—they wore the Science for the People buttons for which they had asked us.

So also did some of the AAAS support staff. It was therefore a surprise to a few of us who were working the lit tables when the flash of a Polaroid camera came from the direction of a friendly Science for the People button-wearing Black woman registrar. Did she not know of the boycott of Polaroid products in protest of Polaroid’s role in the oppression of Blacks in South Africa and in Cambridge, Mass.? One of us went to speak with her and two of her colleagues. A white woman argued against the boycott, saying Polaroid had nothing to do with apartheid or racism, “All they want is profits. That’s. all they care about.” We agreed. She said, “But if it wasn’t Polaroid, it would be someone else.” Sure, but instead of resignation in the face of these facts we must continue to struggle and draw in precisely those people who know the conditions but whose ability to overcome them is limited by the liberal best-of-all-possible worlds rhetoric and ideology.

And then, after five days of almost non-stop activity, when all were amazed at the fact that they were still awake, after a 32-hour stretch that began with the “Flying Squads,” continued through the demonstration, through an all-night meeting, through the Bundy confrontation, through a long criticism session—then came the party. The party was really a celebration, but not because it had been planned this way. It was a celebration because everyone had struggled with themselves, with each other, and with the established order we hate so much, and everyone felt that to a certain degree what was right had come out on top. People had practiced the concept of consensus, of everyone struggling together to arrive at decisions that everyone finds acceptable rather than just voting. People knew each other’s personal strengths, weaknesses, convictions, and emotions. People had been relying on each other collectively through tense and frightening situations, and Thursday night, when it was all over, when everyone was still alive and unhurt, the excitement of the week poured out in a fine demonstration of joy and love.

Women, who have been dealing for some time with the breaking down of barriers between themselves, were the first to get into the spirit of collective love. They danced together, with as much pleasure as when they were dancing with men. Gradually the spirit of the party was incorporated in the form of the dancing: everyone was in a large circle holding on to the person on either side. Men danced with each other without any shame. Good music alone was enough to celebrate about after five days of horrible inescapable canned music in the hotels. And the big circle went round and round, until people began to go off to catch a few hours of sleep before setting off for their cities and another year of study, action, and the building for bigger and better things to come.

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 2 <<

REFERENCES

- See e.g. the February 1971 issue of Science for the People, Vol. III, No. 1 for an account of the actions at the 1970 AAAS meeting.

- For example, Irving Louis Horowitz, ed., The Rise and Fall of Project Camelot, M.l.T. Press (1967).

- Reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, December 29, 1977.

- AAAS Director Barry Commoner, quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle, December 29, 1971.