This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Turning Prescriptions into Profits

by Concerned Rush Students

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 9, No. 1, January/Februrary 1977, p. 6–9 & 30–32

Turning Prescriptions into Profits

The drug industry is expert at making a profit. For the past 10 years, it has either been the first or second most profitable of all industries in the U.S. At the outset, we must decry the immorality of an industry exploiting people’s suffering and diseases, turning it into the most profitable business in America.

Our criticism of the profit motive must go deeper. According to our country’s leading economists, businessmen, and political leaders, the basic principle of business is the maximization of profits. They maintain that production for profit is what makes our economic system work. However, the present economic crisis (inflation, fuel and food shortages, unemployment, New York City approaching bankruptcy) has led the majority of Americans to question whether our economic system is really working at all. A recent national poll found that 55 per cent of the public rate the nation’s economic health as “poor” or “below average;” 33 per cent believe “our capitalistic economic system has already reached its peak and is now on the decline.”1

How does this production for profit work? Let’s examine this question closely with respect to the drug industry, purportedly in business to improve people’s health, and ask how the drive for profits affects the industry’s response to people’s health needs.

| Year | Profits after taxes as a percent of stockholders equity

All drug manufactuerers |

Profits after taxes as a percent of stockholders equity

All manufactuerers |

Profit rank of the drug industry among all manufacturing industries* |

| 1956 | 17.6 | 12.3 | 2 |

| 1957 | 18.6 | 11.0 | 1 |

| 1958 | 17.7 | 8.6 | 1 |

| 1959 | 17.8 | 10.4 | 1 |

| 1960 | 16.8 | 9.2 | 1 |

| 1961 | 16.7 | 8.8 | 1 |

| 1962 | 16.8 | 9.8 | 1 |

| 1963 | 16.8 | 10.3 | 1 |

| 1964 | 18.2 | 11.6 | 1 |

| 1965 | 20.3 | 13.0 | 1 |

| 1966 | 20.3 | 13.5 | 2 |

| 1967 | 18.0 | 11.3 | 1 |

| 1968 | 17.9 | 11.7 | 1 |

| 1970 | 15.5 | 9.5 | 2 |

| 1971 | 15.1 | 9.1 | 2 |

| 1972 | 15.3 | 10.3 | 2 |

| 1973 | 18.1 | 12.4 | 1 |

From Burack, New Handbook of Prescription Drugs

The Cost of Drugs

In 1972 the industry’s sales totaled 6 billion dollars. Out of that total, the industry admits that $800 million went directly towards drug company profits. However, this does not include the $1.2 billion wasted on advertising which is largely directed toward expanding sales to increase profits.2 Capitalist economists erroneously portray our market system as obeying “the law of supply and demand”—if people need a certain drug (demand), profit will motivate a company to supply it; if the drug is not needed, the lack of profit opportunity will discourage unnecessary production. In reality, drug companies both supply the drugs and, through advertising, create the demand. The massive expenditures of the drug companies on advertising reflect the importance of this creation of demand to the sellers of drugs.

The drug companies frequently cite the high cost of research and development as a justification for high drug prices, but research costs are only a fourth of the amount spent on advertising.3 While ostensibly a scientific, health-promoting endeavor, research is, in fact, carried out in order to increase profits. According to Chemical and Industry magazine:

“It is almost impossible to overstress the importance of R & D (Research and Development) expenditures. Above all, regular new marketable discoveries are absolutely vital in the fight for (increasing) … sales.”4

The kind of research that is done is dictated by these commercial considerations. In 1968 the Senate Monopoly Subcommittee concluded that 80-90 per cent of drugs newly developed were so called “me-too” drugs. These are “drugs which are not significantly different or better, and represent little or no improvement to therapy, but which are sufficiently manipulated in chemical structure to win a patent.”5 Thus only the drug company which is able to carve out for itself a greater share of a particular therapeutic market derives any benefit from this research. These drugs could perhaps be justified if they were offered at prices substantially lower than the products they duplicated; however in most cases they are introduced at the same or higher prices.6 The public must bear the costs of this kind of research through higher drug prices.

On the other hand, much needed research and development is not done in areas where profits would not be forthcoming. A dramatic example of this is the drug lithium, which is now widely used by pschiatrists for “manic-depressive disorders.” Lithium is a natural element. Thus, although cheaply and readily available, lithium is unpatentable and therefore considered unprofitable. While reports claiming lithium’s effectiveness appeared as early as 1949, no drug company took an interest in investigating the drug. In 1966 it appeared that no company would even produce the drug. The situation soon changed when researchers recognized the need for slow-release lithium tablets, a form that could be patented.7 8

Once a drug is developed, it must undergo a series of trials in humans which theoretically insures its safety and effectiveness. The industry has been sharply criticized for the way it conducts these studies. In a society where drugs were genuinely being developed for the public interest, one would imagine that there would be a high degree of voluntary participation in drug trials. Volunteers would benefit both as individuals (who might potentially need the drug) and as members of a society whose medical knowledge would be increased. In our society, however, people rarely volunteer to participate in drug testing. They justifiably identify little common interest with the drug industry. In fact a recent poll showed that the American people feel “the drug industry is currently the number two corporate villain, second only to the oil industry.”9 Instead, the industry creates volunteers through various unethical and coercive practices.

The president of the PMA, (Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association) admitted that 85 per cent of the preliminary drug testing is done on prisoners- a group which is not in a position to freely exercise its rights.10 Doctors from Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center were infecting prisoners with malaria to test antimalarial drugs until quite recently. Third World people are another group often exploited for controlled clinical trials. Birth control pills were studied on Puerto Rican and Mexican American women, some of whom were unaware that they were receiving placebos (fake, inactive pills) and as a result become pregnant.11 Such human costs are not tabulated in the corporations’ research expenditures but must be added to the costs society bears.

Monopoly Marketing and the Limits of Regulation

Conceding that drug prices are needlessly high because of the hundreds of millions of dollars that go towards profits, advertising, and socially wasteful research, many will still defend our present system. They argue that this is a small price to pay to maintain our free competitive marketplace. For it is in the marketplace that the consumer exercises real power by choosing among competing products. However, this idealized dream is contradicted by the reality of drug marketing, which is best described by a single word— monopoly.* 12 Three-quarters of all prescription drugs sold in the United States can be obtained only from a single manufacturer or source.13 In those areas where multiple sources of drugs are available, brand-name prescribing practices often preserve the monopoly of the company holding the original patent. A 1975 study of 7 antibiotics no longer under patent (penicillin VK, penicillin G, tetracycline HCl, oxytetracycline, ampicillin, erythromycin and chloramphenicol) showed that for five of the seven, the most widely sold version of each was the one with the highest price! The limited scope of competition in the sale of these 7 antibiotics costs consumers an estimated $180 million each year.14

These marketing practices and promotional activities are a source of concern to many of us. Each day, the F.D.A. has its hands full policing the activities of the drug corporations. It would be tempting for the rest of us to sit back, watching this game of cops and robbers and cheer for the “good guys” -the F.D.A. However, we think the issues must not be viewed in terms of “good guys” and “bad guys” but rather in terms of an entire system of private control of drug production. The F.D.A.’s role is to prevent the worst abuses of that system. It will never challenge the fundamental problems of drug production for profit.15

The F.D.A. has no control over the monopoly structure of the drug market, cannot redirect research into socially beneficial areas, has no way to limit the amount spent on advertising, and has no control over the cost of drugs.16 Thus the F.D.A. vs Industry battle is really a very limited one. Likewise, the debate between those favoring change through more governmental regulation and those advocating less regulation is also a narrow one, since the system of production for profits is accepted as given.

We must take an honest, fresh look at the problem. The goals of these corporations are inconsistent with the goals of a healthy society. Rather than prescribing a symptomatic solution which tries to patch up irreconcilable conflicts, we must attack the underlying problem. We must struggle for a system that works for people, rather than trying to “beat the system” that doesn’t. Our current system works very efficiently—towards making profits. The alternative is one whose goals are the fulfillment of human needs—working towards making people healthy.

The Politics of Expansion in the Third World

The strategy of the drug industry, like other American industries, has called for expansion of its markets and domain both outside and within the U.S. Taking advantage of their vast promotional resources, drug companies have penetrated foreign markets and become dependent upon them for a large proportion of their profits. In 1974, the PMA candidly stated that,

The contribution of sales and earnings of the pharmaceutical industry’s business outside the U.S. continues to increase—for some of the larger PMA member companies it approaches half the total.17

Furthermore, many companies have taken advantage of the availability of cheap labor and tax shelters to move portions of their operations abroad. By recently moving to Puerto Rico, some American companies have been able to achieve a 40 per cent profit after taxes. As one investment analyst commented, “the most important recent discovery of the research-minded drug industry was Puerto Rico.”18

Furthermore, many companies have taken advantage of the availability of cheap labor and tax shelters to move portions of their operations abroad. By recently moving to Puerto Rico, some American companies have been able to achieve a 40 per cent profit after taxes. As one investment analyst commented, “the most important recent discovery of the research-minded drug industry was Puerto Rico.”18

A 1975 study funded by Consumer’s Union found evidence that multinational drug companies “take advantage of a weaker regulatory situation” in Latin America “to pursue labelling and advertising policies of a dangerous kind.” The study showed that the drug companies will recommend the same drug for a wider variety of conditions than they will in the United States. The study also found that the Latin American package labels lacked complete versions of necessary restrictions and potential dangers. Examples cited included big name companies such as Pfizer, Winthrop, and Squibb.19

Winthrop markets Conmel (dipyrone), a painkiller which can cause fatal blood diseases, and is banned from routine use in the United States (“the only justifiable use is as a last resort to reduce fever when safer measures have failed” according to the AMA Drug Evaluations). Packets of Conmel obtained by researchers in Brazil suggested the drug be used for “migraine headaches, neuralgia, muscular or articular rheumatism, hepatic or renal colic, pain with fever which usually accompanies grippe, angina, otitis, sinusitis or tooth extraction.”20

Ciba-Geigy presently markets Entero-Vioform (iodochlorhydroxyquin), a drug of questionable effectiveness for nonspecific diarrhea, in 28 foreign countries. In 1970 the drug was found to cause a serious syndrome characterized by abdominal symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, muscle weakness occasionally progressing to paraplegia, and optic atrophy sometimes leading to blindness. In many countries, Entero-Vioform can be purchased without a prescription; in some, no side effects or warnings are listed in the package inserts.21 And as a last example we note that 92 per cent of the stockholders of Warner Lambert (which now owns Parke-Davis, maker of Chloromycetin (chloramphenicol) voted “NO” to a resolution that the corporation divulge to foreign doctors what U.S. law now demands that it tell U.S. doctors about the side effects of their drug. Chloramphenicol causes fatal aplastic anemia (cessation in production of all blood cells) in a small fraction (1 in 40,000) of people taking the drug.22

The PMA annual report for 1974 notes that ” … previously acceptable norms of corporate operation are assaulted in every part of the world:”23 This “worldwide assault” by those fighting against U.S. corporate influence, and for self-determination, has forced the drug industry to extend itself even further outside the research laboratory into an explicitly political and social realm. The PMA states that it has worked to “monitor developments at home and overseas affecting our industry’s interest and to take direct action where warranted to protect and promote our interests.” They have developed “staff liaison with desk officers at the Departments of State and Commerce, the Agency for International Development (AID) and the U.S. Information Agency (USIA).”24 Thus in collusion with government agencies, these multinational corporations promote their interests—maintaining favorable marketing conditions abroad. The rejection of such foreign control represents an attempt by people in developing countries to determine their own health, economic, and political needs.

Domestically, we see a parallel expansion of drug sales. In addition to the economic effects, what concerns us is the far-reaching qualitative effects of the promotional campaigns. The efficacy of this industry-promoted drug expansion must be questioned on two levels: 1) its distortion of the quality of medical care, and 2) the social-control aspects of this increasing drug dependence (discussed towards the end of this article).

PROPOSALS FOR CHANGE

In our paper, we have shown that the interests of the drug industry are incompatible with good health care. Presently, the industry has tremendous influence over the practice of medicine and a vested interest in maintaining its control. Yet its appearance of omnipotence is quickly shattered when people actively challenge its role in health care. Its vulnerability is especially evident when barriers between health workers can be broken down and strong actions taken together. Only through collective actions can we hope to make real changes. At the same time, we should challenge the drug industry’s presence every day at every level.

Here are some of our suggestions:

- Department chairs and appropriate committees should take responsibility for eradicating brand names from the vocabulary of the hospital community and should begin to develop alternate forms of drug education and practice. This could include seminars on the use and misuse of drugs, floor-wide discussions, and a “generic drug of the month” program as ways to effectively combat the influence of the drug industry on medical education.

- This hospital should follow the lead of other hospitals (e.g. Cook County Hospital, Case Western Reserve Hospital) in banning detailmen from its premises.

- Rush University should end its dependence on drug company teaching materials and representatives as sources of information in the classroom. At the same time, students should refuse to accept gifts and other materials from the industry.

- This hospital should replace the Physician’s Desk Reference as the primary source of prescribing information by calling for a national drug compendium (an official listing of all drugs), and by assuring adequate non-drug-industry sources of information (e.g. Goodman and Gilman’s Pharmacology text, the National Formulary, and The Medical Letter) on the floors of the hospital. Nurses, doctors, and medical and nursing students should make every effort to consult these less biased sources when seeking drug information.

- People should consider first non-drug methods of treatment whenever possible and provide full clear information on side effects as well as benefits when dispensing necessary drugs.

- We should be constantly aware of the drug industry’s influence on medicine and challenge its presence daily on the hospital floors, clinics and classrooms.

- The money currently spent by the drug industry on advertising directed at doctors at Presbyterian St. Luke’s should be reappropriated for the hospital’s patients. This reduced cost would allow the reopening of the hospital clinics that are closed to new “public” patients.

- We must decry the continuing global expansion of the drug industry and the resulting exploitation of people throughout the world. In addition, we must work to end the industry’s invasion of our daily lives and its redefinition of complex social and political problems as medical ones. 9. Finally, we feel that profit has no place in medicine.

—Concerned Rush Students

Barring epidemics, there is a relatively constant incidence of the specific disease a pill can treat. Thus the market for that drug is a fixed one. As a result, drug companies employ the strategy of promoting additional uses to increase drug sales. A brief historical look at this strategy shows how it conflicts with quality medical care.

The period prior to the legislative reforms in 1962 (Kefauver Amendment of the FDA) is filled with examples of unsubstantiated and often falsified claims for beneficial uses of drugs. In the late 1940’s, for example, amphetamines were promoted for at least 39 different ills including “curing” smoking, head injuries, hiccups, heart block, morphine and codeine addiction, and schizophrenia. Even as late as 1969, the industry was making the claim for eleven different medical uses of amphetamines. At present amphetamines are considered indicated for only two medical uses.25 26

In 1962, the Kefauver legislation authorized an exhaustive study by the most established scientific groups in the U.S. They found that, of 4000 drug products legally marketed in the U.S. from 1938-62, only half could be considered “effective.” The other half of the products made by the drug companies had no scientifically proven value. Without any evidence to back up their claims, drug companies actively promoted pill after pill. Prior to their removal from the market by the FDA, these drugs had cost Americans billions of dollars. More important was their effect on the hundreds of thousands of people who received these drugs each year. They could have been better treated with more effective or safer drugs- or no drugs at all!

These ineffective products came from our most “respectable” name companies (including Squibb, Upjohn, Pfizer, Lederle, Wyeth, Merck, etc.) thus destroying the myth that we can only trust “big name” companies’ brands of drugs. If permitted, the drug companies would undoubtedly continue to market many of these ineffective drugs- as many do so abroad.

The history of these abuses is of tremendous importance in understanding the drug industry today. Currently there is a barrage of industry propaganda, that is echoed by many doctors, calling for repeal of the Kefauver-era legislation because it is “too stringent” and “stifles the creativity” of the industry.27 Although it is unlikely that industry lobbying will bring a return to pre-1962 days, we can hardly have any illusions about interests of these corporations. Their actual practice has shown that their primary interest is to expand sales and profits regardless of their impact on medical care.

Drug Expansion into our Everyday Life: Social Control

While we have reviewed the effects of domestic drug expansion on the quality of medical care, another significant feature is the treatment of nonmedical problems as medical ones requiring drug therapy. On the one hand this represents merely an extension of the neverending search for new markets. More important than this quantitative expansion, though, is the entrance of the drug industry into a new realm of our daily lives; we see this as a form of social control.28 A 1971 medical journal advertisement for the Sandoz tranquilizer Serentil illustrates this trend:

The thrust of this ad is to define the tensions of everyday life in our society as pathological. By recommending the prescription of drugs for universal experiences, the potential market for the drugs becomes unlimited. The success of this campaign should not be underestimated. As contrived as the above example and others like it seem, the products they are promoting sell: psychoactive drugs are now the most heavily prescribed drugs in the U.S.29

The industry’s massive campaign urges people to consume drugs as the answer to the alienation of work and home life. Ciba-Geigy suggests its powerful antidepressant Tofranil (imipramine) may help ease the pain when “losing a job to the computer may mean frustration, guilt, and loss of self esteem.” The corporation concedes that their drugs “certainly won’t change these problems” (in the way that programs that fight unemployment and provide jobs that are creative, fulfilling, and worthwhile might), but they can “improve outlook.” Merck’s combination phenothiazine antidepressant Triavil is for those patients who have lately felt “sad or unhappy about the future … easily tired and who have had difficulty in making decisions, difficulty working.” Triavil also treats “the empty nest syndrome,” allowing the “menopausal-aged woman to cope successfully …. after the children are grown and gone.”

Or possibly you’re angry about corporate pollution, the lack of decent, cheap public transportation, or “rip-off’ rates of the utility companies. Before you struggle to change these things, maybe you should first see your doctor.

The favorite anxiety-producing situations depicted over and over again are problems of work (or lack of it), marital conflicts, aging difficulties, and deterioration of urban life. We hardly feel these problems were invented by the drug industry. In fact we would agree with the industry that these problems reflect the major issues facing people in the United States. Today, as these conflicts generated by our country’s social, political and economic policies are becoming more intense, the trend toward the “drugging” of the American people becomes increasingly significant.

These drugs are being pushed in major institutions of our society including schools, prisons, and nursing homes. Schools are increasingly labelling children as “hyperactive” requiring amphetamines to treat their “minimal brain dysfunction.” The number of children given this pseudo-diagnosis** is doubling every 2-3 years. In early 1975, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 children received methylphenidate (Ritalin), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), and other psychostimulants to make them more manageable in school.30

In prisons, those convicts considered “dangerous,” “revolutionary,” or “uncooperative” are targets of a variety of new behavior control techniques. Among these “behavior modifiers” are antitestosterone hormones (to decrease aggressiveness by chemically castrating the subject), major tranquilizers such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine) and fluphenazine (Prolixin), and “aversion therapy” with succinylcholine (Anectine). This last drug is related to the South American arrow tip poison, curare, and causes paralysis of all voluntary muscles, including those of respiration for several minutes. A psychiatrist, an enthusiast for the drug, claims it induces “sensations of suffocation and drowning,” with the subject experiencing feelings of deep horror and terror “as though he were on the brink of death.” in California prisons, inmates have been “treated” wich succinylcholine while the therapist scolds them for their misdeeds, telling them to shape up or expect more of the same.31

In U.S. nursing homes, the average person is given from four to seven different drugs per day, of which 40 percent are central nervous system drugs. Tranquilizers alone comprise 20 per cent of nursing home drugs- far and away the largest of any drug category.32 This high incidence of chemical straightjacketing is the drug companies’ contribution to the shameful way that the elderly are robbed of their dignity and vitality m our society.

Sexism and Drug Prescription

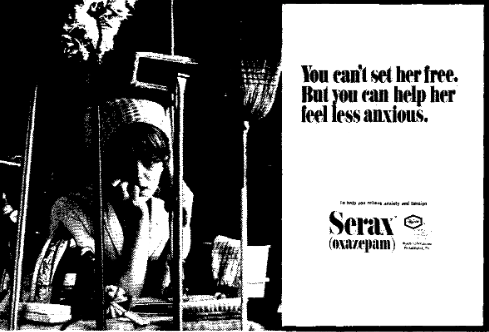

Sixty-seven percent of psychoactive drugs are given to women. Each year 13 percent of the women over the age of 30 receive prescription tranquilizers, stimulants, antidepressants.33 These statistics are particularly significant because they reflect society’s failures to meet the needs of women. Forced to cope with low-paying, unfulfilling jobs, family and child care, and never-ending housework, women often come to doctors with vague complaints of pressures, frustrations, and anxiety. Since 90 percent of U.S. physicians are men, the doctor is usually unwilling and unable to fully comprehend the patient’s complaints. The biases of the male doctor are then reinforced by a drug industry which supports sexrole stereotypes and presents the oppressive reality of women’s lives as an unchangeable fact of life: But the drug company helps to enslave her! Drug ads portray women either as hypochondriacal housewives or as sex objects to titillate the fantasies of male physicians. In this way the drug industry explicitly contributes to the oppression of women.

Fundamental Change vs. Drug-Induced Adjustment

By redefining social and political problems as medical ones, the doctors who are dispensing these drugs are functioning as agents of social control. Despite the sinister sound of this phrase, we believe that most doctors dispense these drugs from a sincere, well-intentioned desire to help those who seek remedy for vague, undefined complaints for which no organic (physical) cause can be found. People do see their doctors for symptoms related to feeling anxious, lonely, depressed, dissatisfied, unhappy, or without purpose to their lives. Such visits comprise up to 1/2 of patient visits to doctors.34 However, these complaints are unquestionably caused and exacerbated by objective social conditions. The drug industry has succeeded in convincing doctors that the symptoms of the ills of our society are actually “personal hangups.” The doctors respond by prescribing a medication, implying to the patient that they have defined the problem and can alleviate it. This substituting of a medical problem for a political problem works as a potent political sedative for preventing social change.

It is obvious to us that the answers to these problems do not lie with drugs or the drug industry. Based on a system of profit, drug corporations can only exploit the conflicts inherent in the oppressive conditions of our society. By pushing drugs to “treat” these problems, they encourage the most narrow, individualistic, and ineffective ways of addressing them. People should not learn to adjust to what they correctly perceive as the deteriorating quality of their lives. There can be no substitute for squarely confronting the ways our society fails to meet peoples’ needs. We cannot depend on easy neat prepackaged remedies; we must develop creative, collective, far-reaching programs to solve these problems

This is the second and concluding part of an article by the Concerned Rush Students, a group of nursing and medical students at Rush Presbyterian St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago. The first part of this article appeared in the Nov.-Dec. 1976 issue of Science for the People magazine. Copies of the complete article can be obtained from:

Concerned Rush Students Box 160 c/o Bob Schiff 1743 W. Harrison St. Chicago, Ill. 60612

1 copy $.50 plus $. 75 postage

3 copies for $1.00 plus $.45 postage

20 copies for $5.00 plus $1.30 postage

This article is also available from

Health/PAC 17 Murray Street New York, New York 10007

Copies (including postage) cost $0.80.

In addition, Health/PAC is also distributing two related articles:

1) John Feltheimer’s “The U.S. Ethical Drug Industry” from Science for the People, July 1972.

2) Rick Barnhart’s “Two Essays on the Drug Industry and its Alliance with the Medical Profession” These are also available at $0.80 including postage.

>> Back to Vol. 9, No. 1 <<

REFERENCES

* The 136 brand names companies comprising the P.M.A. account for 95 percent of prescription drugs sold, with 30 of these companies controlling 75 percent of the market. Through mergers, acquisitions, diversification, and international expansion, large-scale multinational conglomerates are replacing small-scale drug manufacturing firms.35 ↵

** The F.D.A. has recently outlawed the use of the term “minimal brain dysfunction” (MBD) in advertising of these drugs because the term is too vague and there is no evidence of any organic disease. The manufacturers must confine their claims to the symptoms (“hyperactivity,” “short attention span,” “impulsivity”) being palliated. The ruling, in effect, eliminates the pretense of medical treatment and places these drugs explicitly in the realm of behavior control. ↵

- Poll by Hart Research Associates released Sept. 1975 by People’s Bicentennial Commission 1346 Connecticut Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036.

- Goddard, “The Medical Business,” Scientific American, Sept. 1973.

- Ibid.

- “Good Foreign Earnings in the Pharmaceutical Industry,” Chemical & Industry, Feb. 15, 1975.

- Task Force on Prescription Drugs- Report & Recommendations, Select Committee on Small Business, U.S. Senate 1968.

- Ibid.

- N.I.M.H., Lithium in the Treatment of Mood Disorders, 1970.

- Gershon & Shopsin, Lithium: Its Role in Psychiatric Research and Treatment, 1973.

- Cited in Ciba-Geigy Journal, No. 3-41975.

- “Prisoners as Guinea Pigs,” New York Times, Jan. 11, 1976, Section E, p. 9.

- Birth Control Handbook, P.O. Box 1000, Station G, Montreal 130 Quebec, Canada.

- Testimony of economists Comanor (of Harvard), Fisher and Hall (Rand Corporation), Steele (Univ. of Houston) and Schifrin (William & Mary) before Nelson Committee hearings, Part 5.

- F. D. A. Consumer, Dec. 75-Jan. 76, p. 9.

- Council on Economic Priorities, “Resistant Prices,” cited in New York Times, Jan. 6, 75, p. 1.

- For further discussion of the issue of regulation see Ehrenreich in Billions for Bandaids published by MCHR, Box 7677, San Francisco, Calif. 94119. Some of the ways the industry regulates the F.D.A. are described in “Company Town at the F.D.A.,” Progressive, April 1973.

- F.D.A. Consumer (an F.D.A. publication) Nov. 1975, p. 25.

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, 1974 Annual Report, p. 16.

- Silverman & Lee, Pills, Profits, Politics, p. 31.

- “Hunger for Profits,” study cited in New York Times, Aug. 17, 1975.

- Ibid.

- Medical Letter, Vol. 17, p. 105.

- Burack, New Handbook of Prescription Drugs, p. 89.

- For further discussion of the issue of regulation see Ehrenreich in Billions for Bandaids published by MCHR, Box 7677, San Francisco, Calif. 94119. Some of the ways the industry regulates the F.D.A. are described in “Company Town at the F.D.A.,” Progressive, April 1973.

- P.M.A., 1974 Annual Report, pp. 16, 17.

- Pekkannen, The American Connection, 1973.

- Edison, “Amphetamines: A Dangerous Illusion,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 74.

- Nelson Committee Hearings, Part 23, March 1973, p. 9411.

- Much of this section is based on “Health Care and Social Control,” by B. & J. Ehrenreich (Social Policy, May-June 1974, p. 26) and “Pills, Profits and People’s Problems,” by Zwerdling (Progressive, Oct. 1973, p. 44). We must stress that the issue is not whether these drugs help some of the people who use them. Obviously they do. The issue we are addressing is how are these drugs being used by the internists, general practitioners and surgeons, who account for 83 percent of psychoactive drug prescriptions. In this broader context, it becomes both dishonest and cynical to prescribe these drugs as an answer to the problems dramatized in their ads.

- This is true as both a drug category and as individual drugs with diazepam (Valium) being the No. 1 most heavily prescribed, chlordiazepoxide (Librium) No.3. Burack, p. 426.

- Schrag & Divoky, The Myth of the Hyperactive Child, 1975,

- Mitford, Kind & Usual Punishment, 1974, p. 139.

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging Press Release, Jan. 17, 1975.

- Zwerdling, “Pills, Profits, People’s Problems,” Progressive, Oct. 1973 p. 46. Also Fidell, “Put Her Down on Drugs,” available from KNOW, INC., Box 86031, Pgh., Pa. 15221.

- Dreitzel, cited in Navarro, “A Critique of Ivan Illich,” International JI. Health Services, Vol. 5 p. 360.

- Murray, “The Pharmaceutical Industry: A Study in Corporate Power, International Journal of Health Services, Vol. 4 No.4, 1974.