This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

M.D.s in the Drug Industry’s Pocket

by Concerned Rush Students

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 6, November/December 1976, p. 6–9 & 20–21

Concerned Rush Students is a group of nursing and medical students at Rush Pres. St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago. During the past four years, through discussions, weekly literature tables, speakers, films, and written exposes, we have raised the political issues which surround the health care delivered in our hospital. We have also succeeded in making changes. A series of unethical experiments on Black pregnant women was ended through our efforts, as was the segregation of Black and white inpatients on the Obstetrical-Gynecology floor. Our most recent project was an analysis of the US drug industry-one of the most important forces behind medicine’s distorted practices and ideology. We presented the paper as a six-week program to our classmates and the hospital community. We are presently discussing the issue of health-care cutbacks both within our hospital, where elimination of outpatient clinics is imminent, and within Chicago and the country at large. Our goal is to develop a strategy to attack this problem at the level of education as well as direct action. Perhaps most importantly, the group provides support for its members and a constant reminder of the political nature of medicine.

Medical Education and Gifts

“How do doctors get this way?”

—statement by hospital worker at Ob-Gyn Speak-Out, May 1973

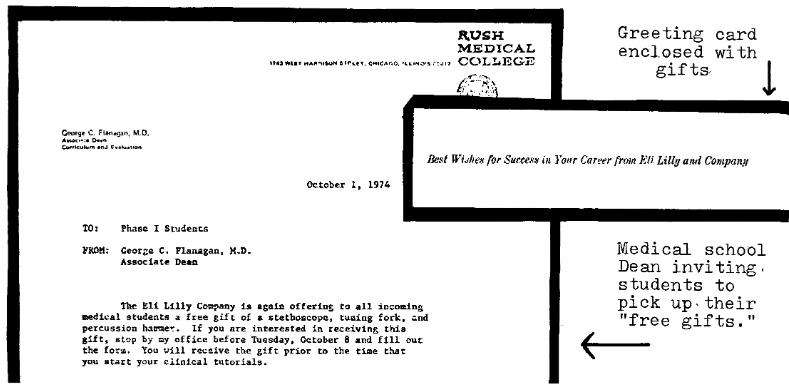

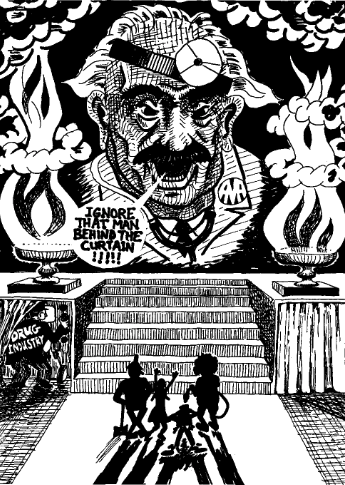

The drug industry works hard to contact and influence students throughout their medical education. In the classroom, drug companies reach students by providing films, slides, speakers, research grants, and even pharmacology teachers. Drug advertising dominates the pages and budgets of medical journals. From the time they enter medical school, students are bombarded with “gifts” of stethoscopes, reflex hammers, pamphlets, and books, culminating at graduation with engraved black bags to keep it all in. Many medical students accept these gifts, and most do so uncritically. Students find these contributions benevolent, helpful, or at worst, innocuous. We think it is crucial to ask why drug companies are so interested in medical students and to analyze the goals and effects of the industry’s “generosity.”

We must understand that the drug companies’ “educational resources,” .their advertising, and their salespeople all have the same ultimate goal: maximization of profits. To quote Dr. Dale Console, former medical director of the E.R. Squibb & Son drug firm:

It seems impossible to convince my medical brethren that drug company executives and detail men are either shrewd businessmen or shrewd salesmen, never philanthropists. They make investments not gifts. 1

Their gifts, literature, and advertising are designed to influence the future medical and prescribing practices of students. These companies know that by the time they receive their degrees, students have well-formed prescribing habits. The industry attempts to establish itself as a legitimate purveyor of information, and as a result, students gain confidence in its products, dependence on its literature and quickly learn the “pill for every ill” concept of health care.

If any student or practicing physician were offered $5000 per year in return for pushing drug industry products, he or she would probably shrink in horror at the prospect of such a bribe. Yet, on the whole, the industry has been remarkably successful in achieving its goals. In return for their $5000 annual investment in advertising per doctor, the industry is able to induce an 89% rate of brand name prescribing, and many millions of dollars of unnecessary drug prescriptions.2

What are the steps in the process which allow the drug companies such influence over doctors? First of all, by opening its doors to the drug company gifts, literature, and representatives, medical schools sanction the legitimate and established place of the drug industry in medical education. The individual beginning medical school is anxious, insecure and uncertain about expected performance and behavior. These initial gifts can convey a sense of importance and identity. Furthermore, these gifts are practical and helpful aids for learning medicine. Students delude themselves by believing they are outwitting the drug industry because they are giving nothing in return for these gifts. However, the “rip-off” of the drug industry by students is a carefully devised strategy on the part of the industry, calculated to maximize the effectiveness of their own rip-off of the American public.

The two essential characteristics of the interactions between medical students and the drug industry are that the student/ doctor increasingly 1) depends upon the drug companies as a source of medical information and 2) accepts passively the industry’s priorities and directions. The drug industry’s strategy is sometimes subtle, but almost always effective. The process is a series of gradual changes for the student becoming a doctor. Students insist that they are fully aware of their own intentions and the drug companies’ involvement with the industry. Eventually, many doctors do give their patients samples of those slickly packaged starter-kits left by the detailmen,3 as well as writing prescriptions for the same expensive brand-name product rather than a less expensive generic one.

We can clearly see that the industry designs its strategy so that no single conscious decision needs to be made by the student to enter into the collusion. It becomes easy for students to deny the reality of this process. When confronted with their complicity, most see the issue as only their individual choice and right to receive a certain gift or prescribe a certain drug. We feel that this view must be challenged so that the drug industry’s manipulations will be exposed and so that medical students and doctors will begin to take responsibility for their actions.

Generic vs. Brand Names

One of the ways that the profit motive of the drug industry distorts health care is illustrated by the issue of generic and brand names. When a new drug is introduced, it is given two names, a generic and a brand name. The generic name is usually related to the class of chemicals to which the drug belongs. The brand name is usually shorter, catchier, and easier to remember. An example of a generic name is chlordiazepoxide, which most people know by the company’s brand name, Librium.4 For the seventeen years of patent monopoly, only the company that developed the drug can market it under either name. After the patent has expired, other companies can market the drug, but only under the generic name or a new brand name; the original brand name (e.g. Librium) is permanently owned by the company that developed it.

Drug companies invest heavily in advertising their brand names to permanently imprint them on people’s minds. Thus, even when the patent expires and other companies start marketing the drug at much lower prices under the generic name, the company continues its monopoly on the market.5 The drug company’s gain, however, is the consumer’s loss-brand name products are consistently more expensive than generic name products, sometimes 10-20 times more costly.

Each time we write or say a brand name, we should examine the origins of the habit. All legitimate sources of informationJ including pharmacology textbooks, medicine and nursing textbooks, and respected medical journals (e.g. The New England Journal of Medicine), refer to drugs by their generic names. To quote the major pharmacology textbooks:

… the immediate answer to the question for most drugs (and the ultimate answer for all drugs) is straightforward. The physician should prescribe by nonproprietary [nonbrand] name.

—Goodman and Gillman 6

Prescribe by generic rather than brand name.

—Lange Pharmacology Review Book 7

There is considerable advantage to prescribing drugs by their official or generic names. This often allows the pharmacist to dispense a more economical product than a trademarked preparation of one company. It would eliminate the expense of each pharmacy’s maintaining a multiplicity of very similar preparations, a saving that could ultimately benefit the patient.

—Goth, Medical Pharmacology 8

Through these sources, students can learn about drugs in a systematic fashion, relating the mechanisms of action, uses and side effects to the particular class of drugs. For example, the name sulfisoxazole helps health workers think about the sulfa group of antibiotics.

Then why does everyone learn the name Gantrisin instead of sulfisoxazole? Brand names are infused into the medical vocabulary through thousands of pages of drug ads, glossy educational booklets and well-labelled giveaways such as pens, rulers, prescription pads, and tourniquets. Students themselves become walking billboards, their pockets stuffed with these trinkets advertising brand-name drugs. None of these sources contribute to a rational, balanced understanding of the products. In fact, their success depends on their ability to do just the opposite. Students learn brand names both directly from these sources and indirectly from their teachers (residents and attendings) whose drug habits have the same origins, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle.

The drug industry argues that generic drugs are inferior to brand-name products. In sifting through the industry’s propaganda, we find that their charge of inferiority takes two forms: 1) innuendoes relating to inferior quality, such as impurities and lack of potency of the chemicals produced, and 2) differences in biological actions inside the body, that is, bioequivalence or therapeutic equivalence.

Current Food and Drug Administration regulations demand that generic and brand-name drugs be chemically identical. In implementing these regulations, the F.D.A. has found essentially equal percentages of brand and generic products failing to meet potency requirements. In 1972 Dr. Henry E. Simmons, director of the F.D.A.’s Bureau of Drugs, in summarizing thousands of tests conducted by his agency, stated, “We cannot conclude there is a significant difference between the generic and brand-name products.” 9

In arguing that there are variations in “bioequivalence” among differing brands of the same product, they mostly contend that different brands achieve different blood levels (“bioavailability”). In some cases they claim a better therapeutic effect for the brand-name product, despite identical blood levels. Meaningful clinical differences in bioavailability have been demonstrated in very few drugs.10 One example considered to be the most important and certainly the most highly publicized is among brands of digoxin (a digitalisderived heart drug).* The industry argues that this “worrisome” evidence of variations in bioavailability among digoxin products justifies physicians’ “fears” of generic drugs. To examine this question, a study was recently conducted of prescriptions written at RushPresbyterian-St. Lukes Hospital, a major academic teaching hospital. Despite the fact that the hospital’s physicians and medical students were aware of the digoxin issue, the drug was prescribed generically 90% of the time! For all of the other drugs prescribed in the hospital, brand names were used for % of the prescriptions. The study concluded that “bioavailability has little to do with the reasons students and doctors use brand names.”11

The drug companies have used this whole issue as a smokescreen for the real issues-rational prescribing, drug costs, and profits. For years they have opposed virtually all attempts to more closely monitor the quality, safety and effectiveness of drugs. Now the industry is hypocritically leading a crusade to protect the public from the “risks of variations in bioequivalence.” Rather than making a meaningful contribution toward ensuring bioequivalence among identical chemical products, they have exploited the issue. Their efforts are directed towards mystifying the problem, leaving health workers and patients sufficiently confused that they can do nothing but trust the reputation of the big name brands. What is needed, instead of trust, is unbiased, constructive research on the biologic effects of drugs.

Prescribing drugs by generic rather than brand name will not solve all of the problems related to drug costs, nor will it solve the abuses inherent in drug production for profits. It would, however, reduce the industry’s ability to fix prices, thus saving consumers millions of dollars per year. More importantly, struggling against the monopolistic power of the industry can reduce their influence over the practice of medicine and further the movement toward “medicine for the people.”

Drug Industry Alliance with the Medical Profession

In every hospital, the drug companies push their products daily in the form of the Physician’s Desk Reference (PDR). The PDR is the bible of prescription medicine, distributed free to most physicians, and found on the wards of every hospital. According to one AMA survey, the PDR is more important in dictating prescribing practices of doctors than are all other forms of drug company advertising. In fact, many people are surprised to learn that the PDR is not a reference of unquestionable objectivity, but actually a collection of paid advertisements. Even though these drug descriptions must correspond to FDA regulations, the presence or absence of a substance in the listings indicates nothing more than the willingness of a company to pay for the inclusion. Inexpensive generic preparations are rarely included in this official-looking volume.12

In contrast to the insidious influence of the PDR is the aggressive salesmanship of the detailman. There is approximately one detailman for every ten practicing doctors in the United States. So at an average of $25,000 per year, detailmen cost consumers $600 million per year.13 Detailmen are present in most hospitals and serve as walking advertisements for their brand-name products. Free of the restraints of government review of written advertisements, these drug pushers can cajole, smile, and handshake their drugs to doctors. They have become a fixture in almost every medical setting, armed with free samples and ready to talk with the first white-coated object they see. They are selected for their good looks and gregarious nature, and use standard sales techniques to encourage the use of more drugs. Physicians often see detailmen as a convenient source of quick information on new drugs, ignoring the strong bias introduced by the detailman’s desire to sell and increase his commission. Detailmen are trained to make the art of selling appear educational.

Drug industry’s influence on medicine is not confined to the PDR and detailmen. The industry sponsors millions of dollars of research in universities, medical centers, and private laboratories. This control greatly influences the priorities of medical research. Researchers, competing for drug industry grants, must demonstrate that their work will be worthwhile to the company. Since the company’s interest is in recouping its investment, it encourages research in those areas most likely to be profitable, and not necessarily those areas most in need of additional research. For example, there is a tendency to concentrate in fields already fully explored, with the hope of reaping quick short-term profits,14 such as diuretics or antibiotics.15

The industry influence creates an environment where scientific data become “trade secrets.” Thus, efforts are duplicated and results are not shared. The latter sometimes delays the recognition of serious side effects that would be apparent from pooled data. Furthermore, academic institutions which depend heavily on drug company research money are reluctant to challenge the company’s practices in their hospitals (e.g. by banning detailmen) for fear of jeopardizing this support. In short, the advancement of scientific knowledge is strongly shaped by the industry’s power and goals.

It seems obvious that the aims of good patient-oriented doctors are very different from the aims of the drug manufacturers. The manufacturers wish to maximize their profits by encouraging doctors to write as many prescriptions as possible, for the most expensive drugs. Good doctors, on the other hand, should want to minimize writing prescriptions and should do all they can to keep the cost of necessary medications as low as possible. It is therefore disconcerting to uncover the coziness between the medical profession and the drug industry.

The separate “competitive” drug firms work together to protect their image and influence through an organization called the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (PMA). During the past fifteen years the PMA has been closely allied with its counterpart in the medical establishment, the AMA. The president of the PMA, C. Joseph Stetler, was formerly general counsel to the AMA for 12 years. The AMA relies heavily on PMA financial support through drug company advertising in all of its journals. In 1973, this advertising support represented 26% of the total income of the AMA. Similarly, the AMA’s retirement fund in 1973 owned stock in 16 companies in the drug or health-care fields. The AMA is even an “associate member” of the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association.16

In return, the AMA has used its powerful well-endowed legislative lobby to support the drug companies’ interests. In 1967 and 1970, they openly and successfully lobbied against passasge of a measure sponsored by Senator Russell Long to establish a system of generic prescribing of drugs.17 This lobbying process included not only “talking” to members of Congress, but also making considerable financial contributions to their campaigns. Since direct political contributions are illegal, the AMA set up the “Physicians Committee for Good Government in the District of Columbia,” channeling funds via this committee to individual campaigns. In the 1972 elections, the AMA was the second leading contributor to campaigns.18

In 1972, the AMA-PMA alliance was made even more manifest in the abolition of one of the AMA’s most vital committees, the Council on Drugs. This committee evaluated all drugs, and published the comprehensive AMA Drug Evaluations, a book many physicians looked to as an independent source of drug information. In the final draft of the second edition of AMA Drug Evaluations, the committee stated that the use of some of the most profitable prescription drugs on the market was “irrational” and “not recommended.” The past chairman of the committee summarizes what happened:

… they (the AMA) did not like the “not recommended” phrases we included in the evaluation of some drugs. They also wanted us to send the book to the drug companies for evaluation. Because we refused, they dissolved the committee.19

The second and final edition of the AMA Drug Evaluations was published with these “objectionable” recommendations deleted. Thus, in each of these examples (PDR, detailmen, research, the PMA) we can see the incompatibility of patients’ interests and the powerful influence of the profit-oriented drug industry. Those examples do not represent cheap shots at some isolated scandals within the industry. Rather they reflect the daily interactions, both at an individual and an organizational level between doctors and the drug industry.

In order to share the ideas and ammunition to offset the industry’s $1 billion annual propaganda campaign, we are making copies of the paper available. There will also be a list of specific proposals for change that is being worked on by those who participated in our programs and will be available in about a month. Write for copies:

Parts I-VI 1 copy $.50 plus $.26 postage

3 for $1.00 plus $.45 postage

20 for $5.00 plus $1.30 postage (our cost)

Concerned Rush Students c/o Bob Schiff

Box 160

1743 W. Harrison St. Chicago, IL 60612

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 6 <<

REFERENCES

* FDA testing now assures that adequate blood levels are delivered by all digoxin products sold. (9) The FDA also monitors a host of other drugs to prevent similar problems. For example, antibiotics are now bio-assayed before marketing and each batch is individually certified by the FDA (10). ↵

- Hearings before the Senate Subcommittee on Monopoly, Select Committee on Small Business (Nelson Committee), U.S. Senate, Part II, p. 4480.

- Burack, New Handbook of Prescription Drugs, 1975, p.xxiii.

- We consider it important to avoid sexist language, and recognize that the word “detailman” negates the existence of those few women the industry does employ to push their products. However we choose “detailmen” rather than “detailpeople” because 1) the reality that virtually all of their salespeople are (white) men, 2) it is a graphic term that most readers associate with the crassest industry practices and 3) we did not want to imply advocacy of more detailwomen as a positive alternative-the role they would play would be equally undesirable.

- In Great Britain, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission recently found Roffman-La Roche guilty of unfair monopoly practices and ordered them to reduce the price of Librium by 60%. The West German government issued a similar order. US consumers pay 700% more for Librium than what the British government considers fair. (HealthRight, Volume II, number 1)

- Antisubstitution laws forbid a pharmacist from substituting a less expensive generic drug for a brand-name prescription. These laws, enacted and maintained through drug-industry lobbying, still exist in 37 states.

- Goodman and Gilman, The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics, 1975, p. 44.

- Meyers, Jawetz and Goldfien, Review of Medical Pharmacology. 1974, p. 28.

- Goth, Medical Pharmacology, 1974, p. 693.

- Silverman and Leed,Pills, Profits and Politics, p. 162.

- “The Pharmacist’s Role in Product Selection,” position papers issued by American Pharmaceutical Association, 2215 Constitution Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20037, March 1971, February 1972. Also see Silverman and Leed, Chapter 6.

- Schiff, R., “Prescribing Practices of Medical Students,” unpublished paper, February 1976, available from Concerned Rush Students.

- Silverman and Leed, Pills, Profits and Politics. 1974, p. 75.

- Goddard, “The Medical Business,” Scientific American, Sept. 73.

- Garattini, “Curative Research for ‘Anti-Economic’ Disease,” Impact of Science on Society (UNESCO), Vol. XXV No.3, Fall 1975.

- For example on of the most heavily promoted drugs at present is metolazone (Zaroxolyn) a diuretic which Medical Letter found added little to an already overpopulated therapeutic field (Vol. 16, p. 77). Similarly there has recently been a proliferation of cephalosporin antibiotics marketed despite being “superflous” to existing drugs (i.e. cephradine (Velosef) identical in effect to cephlexin according to Goodman and Gillman, op. cit., p. 1162; and cephapirin(Cefadyl) discussed in Medical Letter Vo. 16, p. 53).

- Hines, “What’s Behind AMA Drug Suit,” Chicago Sun Times, Agu. 4, 75, p. 56.

- Auerbach, “Drug Firms Gave AMA $851,000” (secretly to lobby against efforts to end industry abuses), Washington Post. July I, 75, p. 1.

- Auerbach, “Sore Throat Gives AMA High Fever,” Washington Post, July 13, 75, p. 1.

- Hines, Chicago Sun Times. Aug. 4, 75.