This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Economics and Population Control

by Nancy Folbre

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 6, November/December 1976, p. 10–14 & 22–23

Intense concern over rapid rates of world population growth burst into the mass media and public consciousness in the late 1960’s with the publication of Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb1 and the Meadows’ Limits to Growth.2 The impact of these studies upon the public lay in their bold assertiveness and attractive simplicity: resources are finite and, given present technologies, the global ecosystem cannot sustain present rates of population growth. Evidence for this, they argued, lies in the “over-populated” areas of the world in which low incomes and abject poverty are the rule. These sweeping generalizations were met by vehement criticism from many quarters. Many scientists argued that the notion of fixed resources was nonsensical; that a flexible, technologically innovative economy would easily cope with such problems. Radicals argued that concern over population growth was merely a smokescreen to disguise the real cause of underdevelopment, the capitalist structure of the world economy.3

Today the controversy over population growth has matured and become more complicated. Demography is one of the hottest new areas for research in the social sciences, giving rise to proliferating studies on the implications of population growth. Private consulting firms, such as General Electric’s TEMPO (Technical Military Planning Organization) have received extensive Agency for International Development funds to provide the intellectual rationale for U.S. sponsored family planning programs.4

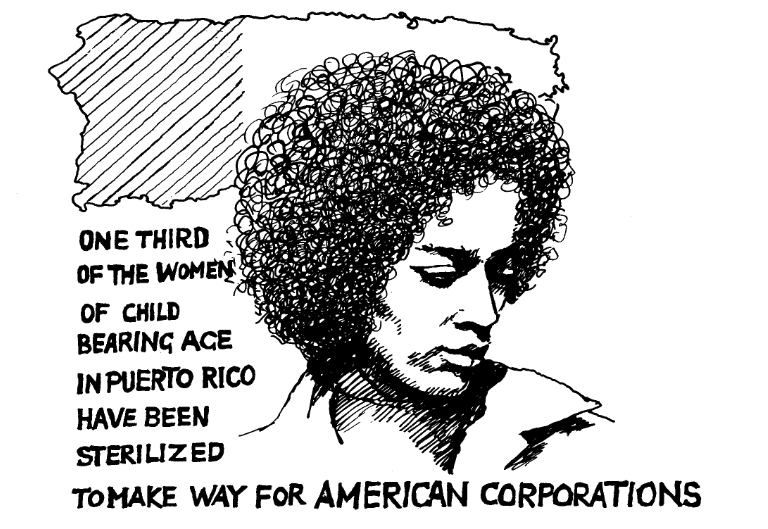

Recent developments in the People’s Republic of China suggest that reduction of population growth in a socialist economy may be a desirable goal. Comprehensive health care programs there have included extensive distribution of contraceptives and education in their use. Simultaneously, events in Puerto Rico and India have shown that family planning may assume vicious forms. Over 40 per cent of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age have been sterilized, many of them without understanding the full implications of the operation. In India, the suspension of civil liberties, and government pronouncements concerning the “need for mandatory sterilization”, have lent an ominous tone to developments there.5

In order to develop an effective criticism of population control, it is important to have an adequate theory of population growth. This article outlines such a theory by examining the role of the family as a unit of production. It offers an explanation of why population growth creates a problem for capitalist economies, focusing on the causes, rather than the consequences of high fertility. It is argued that high fertility persists in many areas because it is economically advantageous to individual families, and a decrease in desired family size will not occur until changes in the social relations of production erode the material rationale behind large families.

Such a transformation of the family production unit occurred through the process of capitalist development in the United States; however, since capitalist growth is uneven and hampered by the imperialist structure of the world economy, this “demographic transition” may not be forthcoming in the Third World. The Chinese example illustrates an- alternative strategy: changes in peoples’ relation to production were effected relatively quickly through political reorganization.6 This analysis suggests that capitalist regimes face a serious dilemma: They would like to limit population growth, but are unable or unwilling to change the economic structures which promote high fertility.

Effects of Population Growth

Despite a great deal of attention being focused on this issue, economists have failed to prove that rapid population growth slows the growth of per capita income in developing economies.7 It is hardly surprising that empirical work has failed to confirm such a broad generalization. The main reason that social scientists have focused upon this generalization rather than upon specific historical case studies of individual countries is that their major concern is the articulation of a theory which posits the developmental ideal of rapid growth within the capitalist framework. In their efforts to construct a theory of underdevelopment which supports a technological, rather than a political solution and calls for the distribution of contraceptives rather than a redistribution of the means of production, they have lost touch with reality.

It is important not to react to these false generalizations with counter claims that are equally unsubstantiated. The question of whether population growth should be slowed should rest upon careful analysis of the economic situation of a particular country. The point is that even if a rapid rate of natural increase does slow the increase of per capita income, its contribution is less than that of the overall political strategy and organization of development. For instance, one of the most striking contrasts in the developing world, that between India and China, can hardly be explained by differences in population density or growth. Nevertheless, radical analyses must go beyond the truism that capitalism, rather than population growth, is the source of underdevelopment.

In many areas of the underdeveloped capitalist world, high rates of population growth together with stagnant employment have increased the reserve army of labor and thrust peasants from small farming areas into wage work. In England and the U.S., the capitalist’s need for cheap industrial labor stimulated changes in land tenure (the enclosures in England, for example) and brought about technological change which freed agricultural workers for factory work. In many areas of the Third World such change has been unnecessary, because rapid rates of population growth and falling rural employment have provided a steady stream of rural-urban migrants. The role of population pressure in proletarianization of the peasantry has been documented in India, Java, and parts of Mexico.8 Such growth in the available labor force swells the “reserve army” of labor, exerts downward pressure on wages, and makes union organization more difficult. This clearly benefits the capitalist class, but, if carried too far, creates its own problems. The lack of transformation in agriculture leads to significant agrarian unrest, a difficulty which many of the now developed countries did not experience.

If technological change does not take place, an increase in the supply of labor leads necessarily to a decrease in the productivity of labor. If the supply of capital and land remains unchanged, more and more workers must share available resources, and their individual contribution to output diminishes. Given the initial assumption, rapid population growth clearly will slow the growth of per capita income. But the assumption is incorrect: Technological change is the essence of economic development. If assumed absent at the very beginning, it can hardly be expected to reappear.

Technological change does not require the introduction of new technology. In most of the underdeveloped world, the problem is the redistribution of available resources and the spread of existing techniques. Political change, rather than new technical innovation, or capital investment, is the key to increased productivity. But the capitalist structure of production is resistant to such change, and therefore, population growth can have a negative effect. Shrewd politicans are increasingly interested in population control in order to stave off political disaster. Decreasing population growth, however, is not an easy task, as the following discussion of the mechanics of fertility declines should demonstrate.

Why Fertility Declines

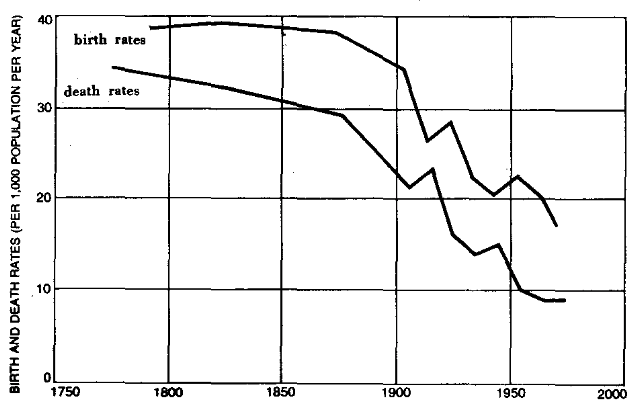

“Fertility”, as demographers use the term, refers not to a population’s potential for childbearing, but to the actual number of children born. There are various measures of fertility which can be used – average completed family size, the ratios of the number of children under 14 to the total population, the ratio of children to women, and others. By any of these measures, fertility has been dropping steadily in the developed countries since at least 1850.9(See graph).

Mortality rates, also shown above, have fallen even faster. Much of the rapid population growth of the 19th and 20th centuries can be attributed to the difference between the rates of decline of fertility and mortality. These rates have fluctuated somewhat, and there are wide differences among countries. Nevertheless, fertility decline may, in the long run,lead to stabilization of birth and death rates and to the achievement of a no-growth population. Analysis of such effects is somewhat confounded by the complicating influence of age structure. For example, in the U.S., a woman of childbearing age bears on the average less than 2 children. However, these young women represent a larger proportion of the population than previously. Even though the fertility rate is now below replacement, the U.S. population will continue to grow for some time. The number of children born in coming years will exceed the number of persons dying, because there will be a great many women having children.

What is particularly striking about this population trend, and not widely enough appreciated, is the fact that it has occurred relatively independently of contraceptive innovations. It is certainly true that the pill, the diaphragm, and the IUD have had enormous social impact, giving women an unprecedented degree of control over their own fertility. However, the history of fertility decline seems to indicate that these technological accessories have been less important than another factor- a decrease in desired family size.

The fact is that contraception is an old art. Though books on the subject, such as Hime’s Medical History of Contraception10 refer to some bizarre remedies such as tying wolves’ testicles about the waist, they also revealed widespread knowledge of condoms, diaphragms, and douches. Coitus interruptus and abortion both have a history older than the Bible. Although such methods are not foolproof on the individual level, they work in the aggregate to reduce fertility considerably. Since pressures to contracept are normally greater outside of marriage, changes in social norms, such as pressure to marry at a later age, may exert great influence upon population growth rates. Simple contraceptive methods were used by the English, the Irish, and the French to slow population growth considerably. Such methods also contributed to a reduction in family size in the U.S. and Japan, where new contraceptive technologies, and, in the case of the latter, legalized abortion, played a more important role.

Metamorphosis in the Home

This decrease in the birth rate has accompanied a larger process of social change which is highlighted by a comparison of women’s roles in developed and underdeveloped areas. Women in the U.S. today give birth to, on average, 1.8 children. They bear these children at a relatively early age. Most women past the age of 30 have already achieved their desired family size and survived the most difficult and time-consuming period of child care. With their offspring safely stowed away in the public schools, they begin a new period in their lives that often includes reentry into the formal labor force. In fact, many women must find jobs to ensure their family’s financial security and provide higher education for their children. Although there are many facts which contribute to the contemporary woman’s life cycle, the drastic reduction in the average number of children born from 7.04 in 1800 to 1.80 in 1973 is obviously central.11

Child rearing has become a less time consuming occupation. The basic needs of reproduction and nurture are met by a family which is less durable as an institution and less stable over time. Many traditional women’s functions have been mechanized or commercialized – cooking, laundry, nursing, babysitting are now services which may easily be purchased. In the United States, over half of the female population between the ages of 16 and 65 are wage workers.12 The housewife’s occupation, shorn of its holy aura of perpetual motherhood, is gradually being stripped of prestige. It is increasingly possible for new forms of sexuality to flourish within the system since they no longer pose a threat to its efficient reproduction.

Contrast this situation with that of women in Third World countries. In urban areas or highly urbanized countries, the number of children per family is not strikingly different from that in the U.S. This is not surprising, since these are the areas in which “Western” culture and capitalist forms of work organization have penetrated. In rural areas, however, in the predominantly agricultural economies which characterize vast regions of the world, the average number of children per family is very high. In Mexico, for instance, most women have borne six children by the end of their childbearing career.13 Women’s fertility is strongly reinforced by cultural norms which value children and childbirth very highly. If a woman’s place is in the home, it is because she hardly has time to leave.

We are not as remote from these women as we may think. The origins of our capitalist economy Jay in subsistence agricultural systems which had some similarities to those in the Third World today. In the U.S., our demographic heritage is startling. It was, in fact, rapid population growth, characteristic of the U.S., which inspired Malthus’ famous Essay on Population. The cultural differences between the colonial population of the U.S. and areas of the underdeveloped world today are immense—but in subsistence agricultural economies the family is a unit of production just as it was in 19th century U.S.

From Large Families to Small

The desire for large families is rooted in the material conditions which define people’s work. In agricultural economic systems where there is little division of labor or production for exchange, children are a valuable resource. Nascent capitalism creates a competitive system in which the family is the chief social unit. Primitive tribal systems (in which there are classic examples of fertility control)14 can provide for the sick and aged, as can advanced state bureaucracies with their welfare and social security institutions. But under the competitive conditions of small farm ownership children are the only source of security. They are an aid not only to aging parents, but to brothers and sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles. Spread out in a variety of jobs, perhaps some of them migrating to the city, some marrying into wealthier families, relatives create a web of security. Those who decide to have fewer children would be penalized. They are deprived of the security which a large family might afford, but they enjoy none of the increases in wages which would occur with a future decrease in the reserve army of labor. Where medical care is nonexistent, and people have grown to expect only the barest necessities of food and clothing, children are not a very large drain on family income. However, their contribution to the family as they grow older is significant.

Oscar Lewis in one of his classic studies of the Mexican family, Pedro Martinez, quotes a Mexican mother, “It didn’t matter to us whether the child was a boy or a girl. Pedro said it was all the same to him. Whatever the ladle brings. All children mean money, because when they begin to work, they earn.” Her understanding is borne out by the budget which Lewis calculated for the Martinez family. Although the parents are only in the-ir 40’s, over half their family income comes from their two adolescent sons.15

Social values bearing on family size reflect the underlying material factors and have arisen historically, in large part, because of them. Other important factors include the sexist roles and authority relations which themselves are products of class structured societies and are often reinforced by religious institutions.

I spent the summer of 1975 doing field work in Zongolica, Mexico, an area in which population has increased ten fold since 1900. While there, I asked women if there were any local herbs they used to prevent childbirth. “Sure,” they said, there were a few, but they were more eager to show me the ones which would guarantee a successful pregnancy. To them, raising a large family implied winning male approval, fulfilling a God-given role, and making an economic contribution to their family’s welfare. As Barry Commoner has aptly put it, “Poverty breeds overpopulation, and not the other way around.”16

In a fascinating study of villages in India where a family planning experiment failed to have an independent impact upon fertility, Mahmoud Mamdani (in The Myth of Population Control) shows that, because the agricultural techniques being used required intensive labor, those property owners who did not have family help at certain times of the year were at a distinct disadvantage. However, in the experimental time period, between 1957 and 1968, there was a significant decrease in fertility in the “control” villages that had no family planning facilities as well as in the experimental villages.17 A gradual process of technological and economic development was having some important effects. Migration and mobility had begun to weaken old ties. Marriage was occuring at a later age as the possibilities of education were being realized. These changes offered new options to women and decreased reliance upon family labor. Family size began to diminish slightly.

Such an autonomous decrease in fertility is characteristic of some Third World areas. However, their transition to lower birth rates is happening at a later stage in their development, and under conditions of much lower mortality than that which occurred in Western Europe and the U.S. Nevertheless, in both developed and currently underdeveloped regions, capitalist development is lessening the economic significance of the family. In a process of proletarianization which is still taking place, family workers and independent producers are being converted into wage laborers. When wage labor offers an alternative to work on family-owned, rented or share-cropped land, the economic incentive for the family begins to diminish. When education offers an alternative to the socialization and training which once took place in the family, the job of being a parent becomes less time-consuming. Profit-oriented institutions begin to replace women’s tasks; corn for tortillas is machine ground, tomato sauce is factory canned. These commodities are produced far more efficiently than their hand-made counterparts, and are therefore cheaper. Until these changes occurred, times spent in caring for children was effectively complemented by useful and productive work performed in the home. To the extent that industrialization proceeds, women’s participation in the formal labor force tends to increase. The benefits each child brings must be weighed against the contribution which the mother’s wages might make to family income. The costs of childbearing increase until they become a liability rather than an asset.

Demographic Transition in the Third World?

This process of demographic transition, if completed, would eventually eliminate rapid population growth. To the extent that economic development occurs, we may expect average family size to diminish and rates of population increase to decline. This expectation is growing among academic demographers.18 Nevertheless, this approach to the theory of population growth is as misleading as the Malthusian assumption that population growth will never abate. There is little reason to believe that capitalist “economic development” in the Third World will occur as it did in the “advanced” countries of Europe and North America.

A growing amount of research documents important differences in the process of economic development in the now developed, or “central” imperialist countries and the dependent underdeveloped areas, or “periphery”. Countries with a history of colonization and continuing European or American penetration of their economies are subject to the removal of economic surplus, which slows their economic growth.19 In their largely foreign owned manufacturing sector, they utilize highly sophisticated technology employing relatively few industrial workers. This leads to a pronounced dualism, or uneven development, between agriculture and industry, country and city, subsistence farms and profit oriented agribusiness. This coexistence of radically different modes of production is reflected in widespread differences in family structure, incomes, and the economic participation of women. In large cities, a relatively larger proportion of women may be employed and women in general have fewer children. Within this cosmopolitan urban context, women may play an important role in national politics. Nevertheless, the vast majority of women play out traditional roles in which large numbers of children are desired. As long as this is the case, no amount of free contraceptives will quell population growth.

China: Shackling the Stork

The contrast between futile Indian attempts to reduce fertility and the Chinese experience in family planning generously illustrates this point. Family planning programs have had enormous success in China, bringing the birth rate down dramatically. Rienert Ravenhold, head of the U.S. Agency for International Development, has gone so far as to comment that within 10 years, China’s birth rate could be lower than this country’s, An April 12, 1976 Wall Street Journal article describes “A Success Story in China”.20 The October 1975 issue of the Population Council’s Studies in Family Planning provides many details of the nature and structure of the family planning program.21 Its distinctive feature is the integration of contraceptives into a comprehensive health care system.

The most important element in the Chinese model, which makes it virtually inapplicable to underdeveloped capitalist countries has been the integration of family planning into a transformed institutional setting which more adequately serves collective needs. For instance, social security in old age is no longer dependent upon the immdeiate family, but rather on the commune. There is also less economic incentive for children because their labor goes toward improving the commune, rather than aggrandizing the family. Women have an important role in production which supercedes their child and house care functions. Even the Wall Street Journal acknowledges the importance of these factors:” … many China specialists attribute the family planning successes more to the unusual nature of’ Chinese society.”22

It is also true that government policies have played a role, raising the recommended marraige age to 28 for men, 25 for women; in many communes the production brigade itself has a subcommittee which decides upon the desired rate of natural increase, and, if necessary, “allocates” births to those who have fewer children and desire more. The weight of tradition might lead to a suspicious response to government dispensed contraceptives, but their distribution has been integrated into a larger health care delivery system which enjoys not only the confidence of the people, but also their widespread participation through the training of “barefoot doctors” or lay medical people.

There is no doubt that such a process of fertility reduction operates partially through the development of new norms concerning family size, and strong social sanctions against early marriage or high fertility. Therefore, it has a coercive element. However, there are no legal penalties in China for “undesirable” reproductive behavior. In contrast, in India legislation concerning forced sterilization is pending in several states. Government officials have said that, with civil liberties suspended in India since June, 1975, the “time is ripe for tougher action on population control.”23 (See box)

INDIA: PIONEERING DEMOGRAPHIC FASCISM

The Indian State of Maharashtra has taken thelead in legislating forced sterilization and several other states are close behind. Under a proposed law, men who fail to be sterilized after the third child face jail sentences with sterilization followed by parole, loss of employment, exclusion from housing and refusal of medical assistance. One of the chief technocrats involved, Dr. D. N. Pai, Harvard-educated Director of Family Planning in Bombay, described last minute changes in the Maharashtra bill as “sugar coating to make it sound a little nicer and not scare people.”

When the bill becomes law, one million men in the state will become eligible for sterilization. Dr. Pai dismisses the “abuses”, which in the past included deaths and round-ups of childless men. “If some excesses appear, don’t blame me … The excesses occurred in all fields. You must consider it something like a war. There could be a certain amount of misfiring out of enthusiasm. There has been pressure to show results.” The bill rewards people who inform on their neighbors. Society, Pai says, must act against “people pollution.”

Forced sterilization of males has limitationsespecially if organized resistance develops. Accordingly, international population planners are looking to new technology. One candidate is a vaccine now being developed in India with U.S. funds which utilizes a woman’s immune system to terminate pregnancy. Following a single injection, the woman is presumably ‘immune’ to the successful development of a fetus for years. A few unanswered questions remain, these are the object of animal studies and studies on “small groups of women” in various countries. The attraction of this new fix is high. Dr. Sheldon Segal of the Population Council says, “such a vaccine would be a tremendous advantage”, particularly in the Third World where people are accustomed to injections and realize that injections can do good. It could be easily integrated into other immunization programs.

In the state of Kerala population growth has been declining. At the local level, Kerala’s several communist parties have been a strong progressive force. Kerala has repeatedly had one of the communist parties voted into statewide office only to have it removed by edict of the central government. The communist parties have contributed to major gains in social services – education, health care and social security – and in employment. Many population experts now acknowlege these gains as the real reasons for Kerala’s declining birth rate.

Bob Park

The Future

The history of population dramatizes the relationship between the family and the larger organization of production. The family is one of a complex of complementary structures which both mirrors and reproduces the larger society. As the family loses its integrity as a unit of production, either through rapid capitalist development or socialist revolution, its reproductive “logic changes. At the same time, the dynamics of the family can give rise to economic change; it can create demographic pressures which expose the limitations of the capitalist organization of production.

Population control is on the agenda for capitalism (or the following reasons: Despite a great deal of state participation in economic planning, most Third World governments have been unable to make significant economic growth happen. Even when it has happened (e.g. Brazil), their inability to meet the basic needs of people has been exacerbated by rapid rates of population growth. They are caught in a basic dilemma. Until they reach certain levels of industrialization, female labor force. participation, and education, there will be no incentive for families to reduce their size. But current rates of population growth, as well as their position in the world capitalist system and internal class structure, are slowing the economic development which could lead to demographic transition. In their rural, family centered, competitive economies, families want large numbers of children. The ruling classes are fully aware of the pressures this creates, but are unwilling to change the social relations of production, because this will undermine their own hegemony. Because their ability to persuade, cajole, or bribe women to voluntarily use contraceptives is severly constrained, legal sanctions, forced sterilization and new technologies like injectible contraceptives, will become increasingly widespread, unless challenged. The fight against the misuse of contraceptive technologies must become part of the larger struggle for democratic control over employment, social services and education. Only the formation and expansion of organizations such as peasant leagues and labor unions will give men and women the power to defend themselves against coercion, and to organize for new alternatives in both production and reproduction.

Nancy Folbre is a graduate student in economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Before that, as an undergraduate, she was a Latin Americanist at the University of Texas. She is an active contributor to Dollars and Sense, a publication of the Union for Radical Political Economics

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 6 <<

REFERENCES

- Ehrlich, Paul, 1968, The Population Bomb, New York, Ballantine Books.

- Meadows, Donella, et al. Limits to Growth: A Report to the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York, Universe Books.

- Mass, Bonnie, 1972, The Political Economy of Population Control Editions Latin America.

- Brown, Richard, 1974, Survey of TEMPO Economic-Demographic Studies, Washington, D.C. GETEMPO Center for Advanced Studies.

- Wall Street Journal, April 16, 1976.

- Wall Street Journal, April 16, 1976.

- Conroy, Michael, and Nancy Folbre, 1976, “Population Growth as a Deterrent to Economic Growth: A Reappraisal of the Evidence”, occasional paper prepared for the Project of Cultural Values and Population Policy of the Institute of Society, Ethics, and the Life Sciences, Hastings-on-Hudson.

- Grigg, D1/2B1/2, 1976, “Population Pressure and Agricultural Change,” in Progress, in Beographym C. Bonds, R.T. Chorley, D. Haggett, D.R. Stoddard, editors, Edward Arnold, LTD, London; and Folbre, Nancy R., 1976, “Population Growth and Capitalist Development in Zongolica, Veracruz,” Latin American Perspectives, forthcoming.

- Westoff, Charles, 1974, “The Population of the Developed Countries”, Scientific American, September 1974, p. 112.

- Himes, Norman, 1963, A Medical History of Contraception, New York, Gamut Press.

- Smith, Daniel Scott, 1974, “Family Limitation, Sexual Control, and Domestic Feminism in Victorian America”, in Clio’s Consciousness Raised, ed., Mary Hartman, Lois W. Banner, Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- Women’s Study Group, 1976, “Loom, Broom and Womb: Women in American Economic Development Radical America, Spring, 1976.

- Mexican Census, 1970.

- Armelagos, George, and Swedlund, Alan, 1976, Demographic Anthropology, W.C. Brown, Publishers, New York.

- Lewis, Oscar, 1967, Pedro Martinez8, Vintage Books, New York. This quote implies that there is no sex preference in Mexican families. However, other sources indicate that male children may be preferred – they make an even contribution to the family budget than do females.

- Wall Street Journal, April 16, 1976.

- Mamdani, Mahmoud, 1973, The Myth of Population Control, Monthly Review Press, New York.

- Kirk, Dudley, 1972, “A New Demographic Transition?” in Rapid Population Growth, National Academy of Science, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press and Beaver Stephen, Demographic Transition Theory Revisited, Lexington, Mass. D.C. Heath.

- Baran, Paul, 1959, The Political Economy of Growth, New York, Monthly Review Press, Andre Gunder Frank, 1969, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, New York, Monthly Review Press, Samir Amin, 1974, Accumulation on a World Scale, New York, Monthly Review Press.

- Wall Street Journal, April 12, 1976.

- Pi Chao Chen, 1975, “Lessons from the Chinese Experiences and its Transferability,” Studies in Family Planning, vol. 6, no. 1.

- An excellent analysis of changes in the Chinese family structure which offers some perceptive criticisms of the Chinese system is Judith Stacy, 1975, “When Patriarchy Kowtows: The Significance of the Chinese Family Revolution for Feminist Theory”, Feminist Studies, vol. 2, no. 2-3.

- Wall Street Journal, April 16, 1976