This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Three Views on Alternative Technology

by Phil Bereano, Eric Entemann, Fred Gordon, Kathy Greeley, Ray Valdes, Peter Ward, Chuck Garman, & Ken Alper

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 5, September/October 1976, p. 5–7 & 33–35

In the last few years, a sizeable movement has sprung up which criticizes the technology of the economically advanced countries, and which is trying to develop and build “alternative technologies”. The Magazine General Meeting (the bi-monthly meeting of the Boston Chapter to evaluate the magazine) urged that Science for the People should begin to report on this movement and to evaluate its political significance. We begin here with a short description of the alternative technology movement, adapted from a brochure written by the New England Network for Appropriate Technology. There follow three analyses of the alternative technology movement with differing evaluations of its political promise. We encourage contributions from readers on this topic.

What is Alternative Technology?

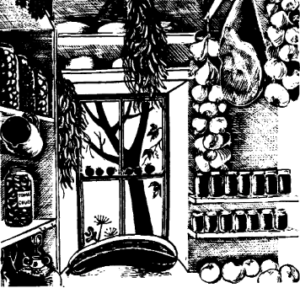

E.F. Schumacher coined the term “intermediate technology” in 1973 to signify “technology of production by the masses, making use of the best of modern knowledge and experience, conducive to decentralization, compatible with the laws of ecology, gentle in its use of scarce resources, and designed to serve the human person instead of making him[sic] the servant of machines.” Today, the term “alternative technology” is more frequently used to express these ideals. The central tenet of alternative technology (AT) is that a technology should be designed to fit into and be compatible with its local setting. Examples of current projects which are generally classified as AT include building of solar collectors for heating and cooling; developing small windmills to provide electricity; roof-top gardens and hydroponic greenhouses; fish tanks in basements; and worker-managed craft industries. Some groups argue that only small community-based technologies should be called AT, while others argue that larger-scale technologies like factories are appropriate in certain situations and should not be absolutely excluded. There is general agreement, however, that the main goal of the alternative technology movement is to enhance the self-reliance and self-sufficiency of people on a local level. Characteristics of more self-sufficient communities, which it is hoped that AT will be able to facilitate, include: 1) low resource usage coupled with extensive recycling, 2) preference for renewable over nonrenewable resources, 3) emphasis on environmental harmony, 4) emphasis on small-scale industries, and 5) a high degree of social cohesion and sense of community.

What are Some Examples of AT Activities

The New Alchemy Institute at Woods Hole MA and also California is currently experimenting with fish and algae eco-systems, and is building a completely autonomous house, which integrates food production, energy generation, and waste recycling, on Prince Edwards Island. Intermediate Technology (associated with Schumacher’s group in England) in Menlo Park CA is developing a small-scale glass factory and other projects for Third World countries. Boston Wind teaches design courses on wind power and other AT in the Boston area. Sun Tek of Cambridge, MA, Solarwind of East Holden, ME and Total Environmental Action of Harrisville, N.H. all do design-work consulting on solar energy. The New England Solar Energy Association publishes a newsletter and serves as a general forum for groups developing solar energy and related AT. Grant County Community Action Council Inc., Moses Lake, W A, is developing a guide for constructing a solar water-heating system which can be assembled at minimum cost with common tools and materials. Earth Mind in Saugus CA designs windmills and solar colectors. The New England Food Coop Organization (NEFCO), a federation of all the food coops in the Boston area is currently working with the Natural Organic Farmers Association (Plainfield VT) to develop a direct link between organic farmers and food coops in the New England region. The Shelter Institute of Bath ME is teaching people to design and construct their own homes. The Farallones Institute in California designs, constructs and evaluates 1) innovative, inexpensive ways of building 2) components for self-renewing energy supply and resource recycling 3) improved means of food and fiber production including field crops, aquaculture, and wildlife management. Earthworm is a recycling collective in the Boston area which is finding the reclamation of wastes quite profitable. The Social Ecology Program at Goddard College, Plainfield VT, teaches courses in AT and attempts to apply AT within an anarchist framework. Resources, in Cambridge, has developed a computer data base of 5000 alternative groups across the country. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance in Washington DC is involved in educational and research activities, developing and disseminating information useful to communities and cities seeking to be as self-reliant as possible. Their projects include urban gardening, hydroponics, aquaculture, biological waste conversion, solar and wind energy.

ALTERNATIVE TECHNOLOGY: IS LESS MORE?

Phil Bereano

The following essay has been substantially edited from a longer version which also included discussions of alternative technology as it relates to technological rationality and the technological imperative, and considered the post-scarcity potential suggested in the work of Murray Bookchin.

Over the years articles in Science for the People have dealt with the political, economic, and social implications of specific technologies in such areas as genetics, contraception, and weaponry. Some have also dealt with the determinants of specific technological forms. But the magazine has rarely addressed the notion of the “technological society,” that is, the intellectual and political ramifications of a culture which is historically unique in its intensive reliance on technologies and on “technological rationality” as a mode of thought. As political people, as technically oriented political people, such an analysis is important if we are going to be able to decide what we should be doing now.

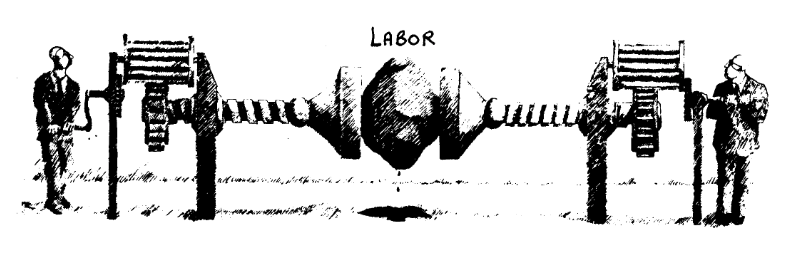

A critical aspect of the discussion of issues of technology and social change relates to the definition of “technology.” I believe that technology does not refer to hardware alone, but to hardware, software, modes of organization, ensembles of techniques, and the political economy within which they are embedded and utilized. I agree with David Dickson in The Politics of Alternative Technology1 that the means of production, such as machinery, embody the relations of production (e.g., aspects of capitalism, domination and hierarchy) under which they were conceived. Technology must be understood in this sense. Numerous studies of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and elsewhere, by Dickson and others, show that the development of technologies of all sorts (specific industrial machinery, the imposition of the factory system over the “putting-out” system, or technologies which are totally separated from physical hardware such as Taylorism and time-motion studies) were specific responses to the desire by capitalists to pacify the labor force in addition to-or even sometimes in preference to-increasing productivity. Technology is not neutral, and most of the technological forms which surround us today in an advanced capitalist society are the result of management’s need to control labor. The dominant forms of social organization therefore become built into the technological forms.

Consequently, I would define a position which says that current technological forms are frequently associated with alienation, hierarchical control, and domination, and that we must work to develop new and appropriate technological forms as a part of a political transformation. “Indeed, it is only through political change, and in particular through achieving liberation from the economic and political shackles of a dominant class, that the possibility of significant technological change can emerge.”2 What sort of a technology would this be? Let me offer the following suggestive definition: Alternative technology is an attempt to find technological forms which make life easier and better by assisting humanity to overcome the constraints of scarcity, and yet are human-scaled and comprehensible, consistent with ecological processes, durable. They must also be less alienating than the dominant technological forms in industrial capitalism, less disruptive of the social/psychological/cultural fabric, and must also reinforce and be reinforced by decentralized organizational structures.

Several years ago, Peter Harper sketched out most of the important criticisms of alternative technology: AT so far has focused on consumption rather than production, is trendy and gadgety, has a bourgeois flavor about it, and frequently advocates scrounging for materials (which becomes a new competitive process).3 Furthermore, some proposals for alternates to existing technological forms are actually massive or megatechnologies which represent the ultimate in alienation from one’s natural environment. Harper also explores the relationship between technological forms and the work/leisure balance in a society, using the three model societies imagined by Paul and Percival Goodman in their book Communitas. This approach seems particularly fruitful to me because it directly raises issues of values and questions about the kind of society we would like to have after the revolution.

Interest in alternative technology has reinvigorated the debate between socialism and anarchism: centralization vs. decentralization, seizing state power vs. creating new institutions, views of class. The main issues I would like to discuss in this context are (i) the continued validity of a materialist analysis, placing primary emphasis on economics; (ii) the sanctioned modes of thought of contemporary Western society; (iii) appropriate organizational forms; (iv) the distinctions which may exist between technology and society relationships in the Third World as compared to the developed world; and (v) my own views of the drawbacks and dangers in Schumacher’s work. (Since Small is Beautiful is the most widely known statement of an intermediate technology position, I will comment on it in some detail although I feel that Dickson’s book is superior politically.)

Materialism and the Primacy of Economic Analysis

Marxism is a method of analysis and a materialist philosophy. The means of production and productive relationships, such factors as labor, capital, technology and land, are the base of society; and social values, art, laws and government, and religion make up the superstructure. The superstructure is formed and influenced by the base, though this relationship is to a certain extent reciprocal. The corollary has been that analyses of social situations which are focused on economics are considered to be more valid than analyses based on superstructural elements, such as religious tenets. However, by its own terms, the substance of Marxism is rooted in the historical situation of over one hundred years ago (such as existing working conditions, perceptions of the role of technology in social change, the nature of work processes, and the composition of the working class). The situation in our own day, particularly as regards technology, is so vastly different from earlier eras that, while perhaps retaining Marxist methodology it is legitimate-and quite necessary-to ask serious questions about the continued relevance of the substantive conclusions, which were based on 19th-century experience, and the sorts of modifications of them which might be necessary to account for historical changes.

Personally, I have always resisted a perspective which views economics as central to understanding human existence, because I am uncomfortable with the realization that Marxism shares such a perspective with both the leading intellectual welfare economist apologists for corporate liberalism and the most confirmed bourgeois American businessmen. I feel more comfortable with a materialist perspective which recognizes that superstructural elements can exert very important influences on social/historical developments.

The most important part of Schumacher’s book to me is his essay on “Buddhist Economics,” where he attempts to look at human relationships as they might be perceived from the perspective of a different cultural tradition. Schumacher spent some time in Burma studying Buddhism. He states that Buddhism views work as having at least three functions: to give people a chance to utilize and develop their faculties; to enable them to overcome ego-centeredness by joining others in common tasks; and to bring forth goods and services which are needed for an existence proportionate with real human needs. Only the last of these seems to involve materialism, but Schumacher claims that Buddhist economics must be very different from the economics of modern materialism “since the Buddhist sees the essence of civilization not in a multiplication of wants but in the purification of human character.”4

According to Schumacher, a Buddhist economist’s goal would be “the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption,”5 which leads to the point of view that “less is more.” In a humane, liberated, and communitarian society, people would not have to fill their lives with material objects in order to satisfy wants which they believe to be needs. Neither the biosphere or interpersonal relationships would be subjected to continual ravage justified on the grounds of maximizing economic productivity and efficiency. For the first time, economically developed societies have the potential for using technology to escape the constraints that scarcity has imposed on humankind. Perhaps, then, a compelling task for radicals is to focus on the non -economic aspects of life, or at least to develop a vastly different economics. After all, “human needs do not exist for the sake of the economy. Rather the economy exists for the sake of those needs.”6 As Roszak says in his introduction to Schumacher’s book, “We need a nobler economics that is not afraid to discuss spirit and conscience, moral purpose and the meaning of life, an economics that aims to educate and elevate people, not merely to measure their low-grade behavior.”7 Some people are critical of Schumacher’s ideas in part because of his social stratum. “Are the ideas, the contribution of upper-class persons to be rejected out of hand because of their class origins? Or are ideas, actions to be judged on their merits, in relation to how they contribute to the advancement of humanity?”8

According to Schumacher, a Buddhist economist’s goal would be “the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption,”5 which leads to the point of view that “less is more.” In a humane, liberated, and communitarian society, people would not have to fill their lives with material objects in order to satisfy wants which they believe to be needs. Neither the biosphere or interpersonal relationships would be subjected to continual ravage justified on the grounds of maximizing economic productivity and efficiency. For the first time, economically developed societies have the potential for using technology to escape the constraints that scarcity has imposed on humankind. Perhaps, then, a compelling task for radicals is to focus on the non -economic aspects of life, or at least to develop a vastly different economics. After all, “human needs do not exist for the sake of the economy. Rather the economy exists for the sake of those needs.”6 As Roszak says in his introduction to Schumacher’s book, “We need a nobler economics that is not afraid to discuss spirit and conscience, moral purpose and the meaning of life, an economics that aims to educate and elevate people, not merely to measure their low-grade behavior.”7 Some people are critical of Schumacher’s ideas in part because of his social stratum. “Are the ideas, the contribution of upper-class persons to be rejected out of hand because of their class origins? Or are ideas, actions to be judged on their merits, in relation to how they contribute to the advancement of humanity?”8

In Revolution and Evolution in the 20th Century, James and Grace Lee Boggs conclude that “the main contradiction in the United States is the contradiction between its advanced technology and its political backwardness.”9 In Chapter 9 of the Boggs’ book, these issues are addressed as “Changing Concepts for Changing Realities,” and they note:

During the last two hundred years we have been traveling ahead with gathering momentum to make economic development the governing principle in every decision. Now it is necessary for our very existence that we change directions, that we embark on a new road. The old direction, the old road, created by one philosophy, one set of values, has become destructive not only of others but of ourselves as well. The old concepts have taken us on a road where material things have become not just the means but the very end of human aspirations. We have replaced man/womankind as the end and goal of living with the things which we originally created to serve us as means. We now value human beings for their economic possessions and their economic status rather than for their humanity.10

A Reorientation of Our Modes of Thought

I see Schumacher’s book as one of a number of works that are beginning to point the way towards a change in our mode of thinking, and not as a definitive programmatic statement. Many people are now suggesting that the critical analysis of post-industrial society must abandon reductionism and scientific mystique, size and growth, efficiency, centralization and control in hierarchical patterns, concern for means instead of ends.

A radical critique of the existing social order is clearly a necessary condition for any process of meaningful social change, and indeed a great deal of important work by liberal muckrakers and by leftists has been along this line. But a critique is not sufficient by itself to bring about change; with that element must be combined a vision of the alternative. “Man/womankind today needs to redefine what are appropriate social relations. This can’t be done by a plebiscite, by counting noses, or by any other kind of numbers game. It must be done by particular kinds of people projecting another way to live and testing it against certain classes, certain races, certain groups, certain people.”11 In other words, serious utopian writing is based on a belief that the future is not inevitable, but rather that a compelling conception of social goals can help to create the conditions for their own fulfillment.

In the attempt to engage in both theory and practice, we sometimes seem to forget that we are concerned with a dynamic process, both between theory and practice themselves and in terms of the creative new elements which can help both our theories and our practices. In this sense we should read someone like Schumacher to see what, if any, valuable stimulation his ideas might provide to the continued development of our philosophy.

If, as I believe, this era is unique, technologically and historically, then it is of fundamental importance to ask new questions for the time if we are able to seize it. What are some of the elements which might compose such a new vision? Let me indicate some of the areas which seem most relevant for fashioning a humane notion of the future for a highly technologized society, and some of the sources of holistic alternative to the aggressive and destructive technology-enthralled present.

We must begin by reassessing which social processes, institutions, and values are properly categorized as means, and which are to be seen as ends. Foremost among the writers who have analyzed post-industrial society in this manner is Jacques Ellul, who wrote La Technique in 1954 (published in 1964 in English as The Technological Society). Ellul uses the term “technique” to denote “the ensemble of practices by which one uses available resources in order to achieve certain valued ends.” He critically points out that the supremacy of technical thinking in the contemporary era depends upon extolling intermediate values (or means) such as rationality and efficiency as the overriding principles in evaluating social processes, as if they were ends. “And this is what the constant misunderstanding is: it is that the society gives possibilities for human life. So when we challenge it, we seem to be questioning elements that when seen from another viewpoint appear perfectly positive.”12

Technological determinism is a view which basically maintains that whatever can be done technically will be done, should be done, and in this society, is done even if it need not be done. Lewis Mumford phrased the issue in a sophisticated manner when he wrote (specifically about automation, but obviously applicable to technology in a larger sense), “It has a colossal qualitative defect that springs directly from its quantitative virtues; it increases probability and it decreases possibility.”13 In other words, the momentum of a new technology seems to impel its utilization and to make less likely other possible courses of action, perhaps of a non technological nature. This technological momentum seems to me to be particularly an outgrowth of masculinist attitudes in which bigger is better, activity is progress, and “progress is our most important product.” A feminist perspective would urge reflection and vision, particularly of a more comprehensive and less fragmented nature.

One of the foremost critical writers on the ways in which modes of thinking relate to technological activity is Theodore Roszak who specifically links the new social phenomena to an inquiry about scientific rationality and technological society.14 Those who proclaim adherence to scientific socialism ought to address Roszak’s arguments that there are a variety of styles of knowledge. Science and knowledge are not equivalent because knowledge is not merely information but concerns meaning also. For example, nature used to have a meaning to people; now it is meaningless, although the source of much interesting information. Roszak uses the Greek term gnosis to refer to this other kind of knowledge-meaning or wisdom. Gnosis is augmentative, whereas scientific rationality is reductionist and anti-organic. Roszak knows that science appeared on the historical scene as a liberator, freeing people from superstition and a pre-existing confining world view. Although he acknowledges this phenomenon, Roszak says that the scientific method has imposed a tyranny of its own. Mystery, wonder, visions and other nonrational modes of human inquiry and experience have been ruled illegitimate by the definitions of science and socialism alike. Scientific reductionism-the attempt to describe a complex reality by subdividing it into smaller systems, a heavy reliance on modelling, a quest to describe things in terms “objective consciousness” can master, the use of “sub-optimization”-is an approach which robs human beings of a portion of their potential. The resulting emphasis on experts and professionals relating to an increasingly fragmented, nonholistic subject matter, blocks a true understanding of natural and social phenomena. Roszak explains:

Reductionism flows from many diverse sources; from an overweening desire to dominate, from the hasty effort to find simple, comprehensive explanations, from a commendable desire to deflate the pretentious obscurantism of religious authority; but above all from a sense of human estrangement from nature which could only increase inordinantly as western society’s commitment to single vision grew more exclusive. In effect, reductionism is what we experience whenever sacramental consciousness is crowded out by idolatry, by the effort to tum what is alive into a mere thing.15

Organizational Forms

Concern with overcoming dominative forms of thought seems to lead inexorably to new attempts to explore technological and social arrangements which emphasize smallness, simplification, and decentralization. There is a lot of decentralist-anarchist activity going on. Some may be easy to ridicule; some may embody a new variant of the individualistic biases of capitalism. But many are genuinely exciting operations: women’s health clinics (in particular women’s self-help clinics), food co-ops, bookstores, carpentry collectives, printing collectives, trucking collectives, music collectives, dance collectives, and all the rest. Regardless of whether any particular examples are successes or failures, we should avoid criticism that is based on intolerance for the notion of experimentation and the values of creative exploration which sometimes lead to “failures.” Some experimental forms may fail, but a person seriously interested in social change would be attempting to analyze the causes of such failures and to reflect upon them, and to discuss with others whether changes in any fundamental parameters might have produced a different outcome.

But it isn’t sufficient just to be “alternative.” We should examine the explicit politics of each such institution, an if it is in fact an arena for social struggle then it should be supported, even though-just like all struggle situations in this society-it is apt to display contradictions. Perhaps the monopolies can’t be put out of business by these low-production units, but few of the people who are seriously involved in a food co-op thinks that they will put A&P out of business.16 We have historical evidence to warn us that sometimes different and alternative institutional forms become distorted from their original purposes, and may even work against them: some of these alternatives were centralized and even publicly owned, such as the TVA; some of these are in the form of producer co-ops, which may be trying to perpetuate the exploitation of workers (such as the Sunmaid and Sunsweet organizations which are fighting the UFW); and sometimes consumer co-ops can focus on low retail prices in socially regressive ways.17 In some instances, the alternate society effort isolates the people engaged in it from other elements in society; in Britain, when the workers at the Lucas Aerospace Combine presented alternative technology ideas as part of a conversion plank in the course of their labor negotiations, the academic/intellectual AT community did not give them strong support.18 In other words, we should analyze each alternative institution to see whether it serves the people or merely serves its own personnel.

But it isn’t sufficient just to be “alternative.” We should examine the explicit politics of each such institution, an if it is in fact an arena for social struggle then it should be supported, even though-just like all struggle situations in this society-it is apt to display contradictions. Perhaps the monopolies can’t be put out of business by these low-production units, but few of the people who are seriously involved in a food co-op thinks that they will put A&P out of business.16 We have historical evidence to warn us that sometimes different and alternative institutional forms become distorted from their original purposes, and may even work against them: some of these alternatives were centralized and even publicly owned, such as the TVA; some of these are in the form of producer co-ops, which may be trying to perpetuate the exploitation of workers (such as the Sunmaid and Sunsweet organizations which are fighting the UFW); and sometimes consumer co-ops can focus on low retail prices in socially regressive ways.17 In some instances, the alternate society effort isolates the people engaged in it from other elements in society; in Britain, when the workers at the Lucas Aerospace Combine presented alternative technology ideas as part of a conversion plank in the course of their labor negotiations, the academic/intellectual AT community did not give them strong support.18 In other words, we should analyze each alternative institution to see whether it serves the people or merely serves its own personnel.

In regard to the worker-management concept, we must acknowledge that Schumacher is not talking about hippie food co-ops and woodworking shops. The one example of an organization which he discusses at length, the Scott Bader Commonwealth, is hardly such an enterprise. In 1971 its sales were 5 million British pounds, and its net “profits” were nearly 300,000 pounds; 379 individuals are worker-managers in this co-op venture. There is important latent interest in such organizations. A recent poll conducted for the People’s Bicentennial Commission found that only 8% of Americans wanted to work in a nationalized firm, only 20% in a capitalist context, but that 66% would prefer to be in a company owned and controlled by its employees. Why aren’t more radicals actively working on this last model?

Self-management (the French term often used in the literature is autogestion) can have diverse meanings. A literal and limited definition might suggest only democratic management of a firm by its workers. But in a deeper sense, it refers to a system of organization at the national level which would embrace not only the productive system but all of the institutions of society including those with fundamentally political or ideological functions.

By and large, the alternative technology/alternative institution people have not tackled the problems of how the heavy industrial base of a society such as ours might exist in their vision of the future. Organic food restaurants, after all, are not as essential to the economy as are steel foundries. As regards alternative forms of technological hardware, much work remains to be done on this problem; for example, I am involved in an investigation of small-scale steel making which hopes to incorporate, among other things, the experiences in the People’s Republic of China with backyard steel-making during the Great Leap Forward. But, in regard to alternative institutional forms for heavy industry, there is much we can learn about what has been going on in other parts of the world (and some activities in this country). There is self-managed activity in major industrial sectors occurring in Yugoslavia, in the Basque regions of Spain, in Peru·, and of course it existed in Chile under the UP. There is a major worker-owned mine in Vermont.19 In the American Northwest there are still plywood co-ops, and we should study their history and current operations. And, in the service sector, for example, we might look at the experience of International Group Plans, a large insurance company in Washington DC totally owned and run by the 350 people working in it. A network center exists in Ithaca, New York, called “People for Self-Management” to provide such information.20

I am not talking about “self-management” solely as a political slogan, nor am I suggesting that in all of the above-mentioned examples the workers’ political consciousness is fully developed. I am saying that there are exciting possibilities of putting these theories into practice and having these practices molded by conscious politics. I am talking about the technologies-hardware and social/institutional setting- which are appropriate to a radical future.

… [E]ven “workers’ control of production,” a very fashionable slogan these days, would not be any sort of “control” at all if technology were so centralized and suprahuman that workers could no longer comprehend the nature of the technological apparatus other than their own narrow sphere. For this reason alone, libertarian Marxists would be wise to examine social ecology in a new light and emphasize the need to alter the technology so that it is controllable, indeed, to alter work so that it is no longer mind-stunting as well as physically exhausting toil… 21

[At this point the original essay discusses the developed world and ”post-scarcity,” and the importance of scale.]

The Third World

Schumacher has a chapter dealing with neocolonialism, although he is uncomfortable using this term. In another chapter, he deals with the concept of economic development (“primarily a question of getting more work done,” involving motivation, know-how, captial, additional markets for outlet)22 and correctly notes that existing programs of aid have increased the dependency of the poor nations upon the developed ones. Schumacher is primarily concerned with increasing the levels of economic activity, but in several places he recognizes that development is not solely an economic concept; Third World writers are trying to remind us that the concept of development must include a social and cultural aspect as well (and in this regard, many Third World societies are more highly “developed” than our own). Schumacher’s point is that “the choice of technology is the most important of all choices.”23 Most aid schemes totally ignore such an inquiry, and seek to transplant developed-nation technology into a Third World context; and many Left analyses do the same.

Schumacher’s emphasis is on intermediate technology which would be appropriate for the Third World. He notes that “whether a given industrial activity is appropriate to the conditions of a developing district does not directly depend on ‘scale,’ but on the technology employed.” And he goes on to say:

In the end, intermediate technology will be “labor-intensive” and will lend itself to use in small-scale establishments. But neither “labor-intensity” nor “small-scale” implies “intermediate technology.”24

Schumacher does not give an entirely satisfactory definition of what he means by intermediate technology. He relates the concept to “equipment cost per workplace” and he makes it clear that he is aiming for something between the levels of the present indigenous technology of the typical developing country and the enormous scale “sophisticated” technology of the developed countries.2526

As Gandhi said, the poor of the world cannot be helped by mass production, only by production by the masses. The system of mass production, based on sophisticated, highly capital-intensive, high energy-input dependent, and human labor-saving technology, presupposes that you are already rich, for a great deal of capital investment is needed to establish one single workplace. The system of production by the masses mobilizes the priceless resources which are possessed by all human beings, their clever brains and skillful hands, and supports them with first-class tools. The technology of mass production is inherently violent, ecologically damaging, self-defeating in terms of nonrenewable resources, and stultifying for the human person. The technology of production by the masses, making use of the best of modem knowledge and experience, is conducive to decentralization, compatible with the laws of ecology, gentle in its use of scarce resources, and designed to serve the human person instead of making him [sic] the servant of machines. I have named it intermediate technology to signify that it is vastly superior to the primitive technology of bygone ages but at the same time much simpler, cheaper, and freer than the supertechnology of the rich. One can also call it self-help technology, or democratic or people’s technology-a technology to which everybody can gain admittance and which is not reserved to those already rich and powerful.27

To me, this sounds like a very sensible and valuable vision, something worth working towards. In fact, it sounds like just what Science for the People described in impressive detail in the book, China: Science Walks on Two Legs.

Dangers and Drawbacks

In conclusion, let me state that I do not accept all of Schumacher’s ideas and analysis. Much of his analysis is politically naive, and certainly a great deal of it is permeated by an upper-caste point of view.28 It can lead to the mushy and confused politics of a Governor Jerry Brown. Also, Schumacher runs the danger of being paternalistic; how do well-meaning members of a rich society know what is “appropriate” for the Third World? Too much in Schumacher seems to point in the direction of doing one’s own thing. Religious metaphor is used too simplistically.29 But if we are indeed less naive and less paternalistic than Schumacher, why don’t we try to juxtapose his insights with the thinking which has proved most critically stimulating to us. I have tried to do some of that; undoubtedly readers of Science for the People have additional theoretical perspectives they believe are valid. I would like to know what kind of analyses occur when people apply these constructs to that idea that “small is beautiful.”

I wish to thank a number of friends, particularly Les Hoffman, Fred Lee, Sam Salkin, and Susan Schacher, for their criticisms of earlier drafts of this essay.

Phil Bereano has been involved for the past six years in research and teaching on issues of technology and society, at Cornell and currently at the University of Washington.

ALTERNATIVE TECHNOLOGY: POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITATIONS

The form technology takes is determined by the values and priorities of the socio-economic system. As it develops, it reinforces that system. Therefore, when we speak of technology today we must be careful to identify it as a capitalist technology, one that “represents an accumulation of past choices made for the most part by and in the interests of employers.”30 Those who have an interest in controlling workers in order to increase efficiency would have us believe that the technology of production lines, secretarial pools, pollution, hierarchical control is good, that it is necessary, and that it is inevitable.

While “progress” is sold to us as improving the quality of life-in the form of products that relieve us from monotonous labor, move us faster through the air, cook our food in seconds-it has, in fact, alienated us and degraded our lives. Technology for most of us is mysterious and awe-inspiring. Taught to believe in and trust a small group of specialists who supposedly hold the golden key of knowledge, we increasingly relinquish control over our own lives, and are left atomized, frustrated, suffering a vague sense of loss and resentment. Many people are aware of this process and identify technology as the root of evil. They adopt a fatalistic, resigned attitude that this is an inevitable development, a force that has generated a momentum beyond human control.

However, this attitude is beginning to change. Concepts of an “alternative technology” that would somehow restore our control over our lives are becoming credible. For some, alternative technology means nothing more than new inventions which would make technology less imposing and more ecologically sound. Others, however, do not think that we can develop a new way of life out of technology alone. They claim that, in order to develop a meaningful concept of alternative technology, we must determine new values and priorities and the technological forms that would be compatible with them. We agree with this position as far as it goes, but we would add that a struggle for new values and priorities is not merely a matter of moral argument: it involves a political and economic struggle against those who have an interest in maintaining the system as it is.

E. F. Schumacher, author of Small is Beautiful and one of the most influential proponents of an alternative technology, rightly comprehends technology as part of a “form of life,” and sees that different moral outlooks would lead to different technologies. He understands contemporary advanced technology as following from a system of priorities in which work is nothing more than the means for a paycheck, and is thereby degraded. He sees the drive for profit coupled with technologies that lead to the destruction of the environment. And he recognizes that a system in which people treat others as means, and the accumulation of wealth as the end, is one which develops technologies of human surveillance and manipulation.

Schumacher’s work is faulty, however, in that he does not see how both the form of technology and the moral poverty that goes with it are grounded in the economic structure. We maintain that the degradation of work, of human relations, and of the environment arises in large part from the ways that a capitalist economy forces people to behave. In a competitive market, each company has strong pressure on it to maximize its profits by achieving the greatest possible labor productivity at the lowest possible cost, and by maximizing total revenues (price times volume). Such a strategy is not simply the result of greed, but follows from financial necessity. If a particular company does not so behave, it will lack the capital for new investment; its products will become uncompetitive. Such a company has a precarious existence.

There are strong pressures to get work done in the fastest, cheapest manner possible: pressures toward capital intensiveness (the opposite of “small is beautiful”), stultifying division of labor, repetitive tasks, etc. There are pressures toward the degradation of the environment: each company wants to maximize its own profit, and has no practical interest in the conservation of scarce energy resources or in preventing destructive materials from polluting the environment. All of this results in the moral perversion of human relations, for the capitalist must view both worker and consumer as means to capital accumulation; thus the worker is manipulated and suppressed, and the consumer lied to and plotted against by advertisers.

Although Schumacher is against private ownership, and understands it to be antithetical to the kind of society he wants, he sees the struggle primarily as a moral contest between the greedy and the virtuous. He does not grasp how economic structures mold values and create political power. The bulk of his book is, therefore, a moral sermon.

Schumacher’s lack of understanding of the relationship between the economic structure and the values and political relations of a society is apparent in his suggested strategies for social change. Schumacher presents two schemes by which the means of production may be effectively taken from the capitalists and given to the workers and the general public. The first is based on the actual example of the Scott Bader Corporation, a British company producing sophisticated materials-polyester resins, alkyds, polymers, and plasticizers-which was given to the workers employed there by the Bader family in 1951. Since then, it has prospered enormously, while dedicating itself to the development and happiness of the workers, and supporting charitable public causes. This, apparently, is evidence that socialism can be attained through the spreading of a cooperative movement.

Schumacher’s argument is, however, striking in what it omits. There have been a very large number of cooperative experiments, both in the US and in Europe. Rather than review their history, which would show that only a tiny fraction avoided collapse, and that almost all that did survive did so by shedding any significant social philosophy, Schumacher picks a single example of success. Schumacher never, therefore, examines the economic forces that often were important factors in the failure of earlier cooperative ventures. Nor does he consider the possibility that these forces may still threaten the Bader Commonwealth: Why, instead of its prevailing against capitalism, won’t capitalism prevail against it?

What if Dupont or Monsanto, through heavy investment in productive technology, were to produce an identical product at a fraction of the cost? Or if they were to develop, through a massive program of research and development, a new product line that made Bader’s plant obsolete? Or if they intentionally undersold Bader, at a loss, until Bader’s limited financial resources were used up? Bader would have three alternatives: streamlining operations (which may inevitably require the “degradation of work”); bankruptcy; or takeover by a more heavily capitalized firm. The destruction of small companies by larger and more “rational” companies is not an unfortunate chance occurrence. It arises from pressures of capitalist development. But this pressure Schumacher does not acknowledge.

Schumacher’s second scheme is a form of nationalization of all but the smallest businesses. Since in Britain and the US about half of corporate profits goes to the government in taxes, it should upset no one if the number of shares of stock is doubled, and the new shares become government property; instead of taxing the company, the government as a stockholder would get half the total dividends. Once the government has control, it can relinquish effective control to the workers and local governments, and the priorities of the company can rise to a higher moral plane.

Schumacher’s second scheme is a form of nationalization of all but the smallest businesses. Since in Britain and the US about half of corporate profits goes to the government in taxes, it should upset no one if the number of shares of stock is doubled, and the new shares become government property; instead of taxing the company, the government as a stockholder would get half the total dividends. Once the government has control, it can relinquish effective control to the workers and local governments, and the priorities of the company can rise to a higher moral plane.

“The transition from the present system to the one proposed,” Schumacher claims, “would present no serious difficulties;”31 the capitalists are merely giving stock instead of taxes to the government. But either the capitalists are losing power and wealth or they are not. Social welfare programs and high corporate taxes reflect power relations and were won through years of class struggle. Schumacher’s scheme either means that the power and wealth of the capitalists will be preserved-in which case corporations will operate very much as they have in the past, maximizing efficiency and giving wealth to rich stockholders-or that capitalist power and wealth will be destroyed-in which case economic efficiency and maximizing return will not govern production. To believe that the capitalists will allow themselves to be dispossessed without mobilizing all their financial and political power, that the transition from capitalism to socialism “would present no serious difficulties,” is to ignore history.

Even if the social ownership of production could proceed a certain distance, as it has in Britain, so long as a country remains in the international market, forces may very well overwhelm the socialization of the economy. If a country cannot match international rates of capital accumulation, its position in the world market will decline. What ensues is the takeover of domestic industry by the heavily capitalized firms of the US and Germany. The alternative is withdrawal from the international market. Such a withdrawal has often been met by financial and possibly military sanctions by capitalist countries. Schumacher, in summary, does not fully recognize the opposition to a country’s transition to socialism that would arise both domestically and internationally.

Despite the shortcomings of Schumacher and other advocates of alternative technology, the movement as a whole has value for us in that it brings out the fact that the form of technology is not invariable but is a function of the society in which it is found and tends to preserve that society; any movement for social change must include a program for changing technology. A political revolution must be accompanied by a social and technological revolution to be truly successful. The Soviet Union is a clear case where this did not occur. Although ownership of the means of production no longer lay in the hands of a few private individuals, the actual mode of production was never even challenged. Lenin, in fact, advocated adopting the Taylor system of management, applauding it as “one of the greatest scientific achievements” in the field or work and production efficiency. This attitude is one of the factors that led to a state capitalism that was qualitatively little different from western capitalism.

A critique of capitalist technology might have two parts: one would proceed by accepting the predominant social values, showing that capitalism cannot or will not effectively achieve them. The second part of the critique challenges the predominant values of this society and envisions forms of technology which involve different social goals. Accepting the aims of contemporary society, it could be shown that a large number of national health problems-perhaps the majority-are created by industry, either in the plant or through pollution. Industry is able to increase production, profit and new investment because it does not have to pay to prevent these hazards. But it ruins the health of workers and nonworkers alike. To cope with the problem a huge medical empire has grown up, with the medical supply, drug, and research industries (which together amount to ten percent of the average American family’s income32). If occupational health and safety and pollution abatement become major concerns of production units, it would cut direct production of these industries and hurt their profits, for a certain amount of money would have to be diverted from direct production. The resulting improved health would hurt the medical and medical-related industries. That is because one industry substantially exists to exploit the damage done by another. Other examples include the following: Factories leave the cities to cut taxes and so to maximize profits; this makes transportation by automobile indispensible, and so leads to an increase in auto production. Agribusiness practices extensive monoculture; this necessitates the use of chemical insecticides which supports a sizeable industry.

The second part of the critique is less familiar. To a large degree, the values and priorities of capitalism as a system have been incorporated by individuals. Capitalism is not just an economic system, narrowly defined, but a social-moral system which promotes certain human tendencies-e.g. competitiveness, materialism, individualism, the treatment of nature and people as means rather than as ends-and discourages others. The priorities of the system determine how technology will be developed.

For example, the priority of capitalism as an economic system is to maximize profits. This priority, as we mentioned earlier, determines the organization of work; work is governed entirely by efficiency. What follows is the technology of the production line, the dividing up of work into meaningless fragments, the social isolation of the worker, the maximization of the pace of work, the use of industrial processes that workers do not understand (with no effort made to make the work comprehensible to the worker), machinery which the worker cannot understand or repair, etc. To the extent that these priorities have been incorporated by the working class, the result is a consumer mentality.

A critique would point out that this is senseless, that to tum work into stultification, and then turn leisure into enjoyment without any social significance, detached from the “real” world, is a perversion of both work and leisure. What is needed is the reorganization of work; this involves a different technology, e.g. the end of assembly lines. This part of the critique is different from the first in that it challenges values of the society which are very widely held.

The real benefits of any radical political change will not be in terms of an increase in the total number of products available to the working class, but in terms of the reorganization of the whole social and economic system in accordance with values and priorities which are different. An enormous increase in human welfare can take place without any increase in total production, or with even a sizeable decline. What is required is that instead of the criterion of capitalist profit determining what is produced and how it is produced, a standard of human need, to be arrived at through public discussion, will govern. That means the transformation of social, political and productive life, and the transformation of the material life of the society.

The primary value of alternative technology is that it is part of the vision of a good society which might help motivate a movement for political change. In addition, we recognize three ways in which demands for the development now of alternative technologies, or their actual development, might become strategies which challenge the system. We are not at all sure however that these strategies will be effective.

We can envision three strategies, involving alternative technologies, which would challenge capitalism: 1) the demand for technologies which are ecologically sound, 2) the demand for collectively managed workplaces and the technologies to go with them, and 3) the actual use of technologies of self-sufficient production.

1) The demand for technologies that are ecologically sound: Barry Commoner has argued33 that a large portion of economic growth has been bought at the expense of the natural environment. This “capital debt” to the environment must be paid back or else the whole ecological system will deteriorate and finally collapse, taking the economy with it. Commoner argues that this pay-back cannot occur under the present system. He argues that American industry has become too capital and energy intensive. It has purchased increased labor productivity, i.e. output per worker-hour of labor, at the cost of decreased capital productivity. i.e. output per dollar of invested capital. But in order for an economic system to survive it must regenerate its essential resources, in this case capital. The decrease in capital productivity threatens this capability.

Why has the system not collapsed thus far? As the productivity of capital has fallen, increased total production has provided more available capital. However since this capital is being used to finance increasingly capital-intensive production, the process is self-defeating. In addition a greater output per worker-hour and the decreasing amounts of capital available for the creation on new jobs have given us a steadily rising unemployment. Commoner then argues that this whole conflict has been cushioned by the cost of pollution being external to the marketplace. If American industry were forced to bear the cost of pollution, the result would be lower profits and consequently an even greater capital shortage. Capitalism cannot pay the debt; the strain to the economy, says Commoner, would be intolerable. If he is right, the demand for an ecologically sound technology is the demand for a technology which cannot be realized within the context of capitalist economic relations.

It would be very difficult to decide whether Commoner is right and perhaps even more difficult to calculate the implications of his thesis for alternative technology. In one sense at least, Commoner appears correct. American nonfinancial corporations do seem to be experiencing a shortage of liquid capital (e.g. money). Because of the tax structure and the high rate of inflation, many American corporations used debt financing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. With the slowdown in the economy, they were forced to turn to still more borrowing to repay old debts, to meet interest charges, and to extend credit to customers with the same problems. From 1950 to 1974 short-term debt increased from 13% to 30% of the gross corporate product and interest costs have risen from 2% to over 20% of profits.34 This liquidity problem threatens individual corporations with either bankruptcy or takeover by sounder institutions, so they raise the spectre of a national capital shortage. The only way they can solve their problem is by increased profits, which would give them increased capital, and so the demand for an ecologically sound technology, in so far as it threatens profits, does indeed threaten them. However in some ways alternative technology may help American industry through this crisis. Alternative technology could provide a whole selection of products which can be produced by American industry. Labor-intensive technologies may increase the number of jobs (albeit low-paying ones) without the consumption of vast amounts of capital. Small-scale experiments may serve to demonstrate that ecologically sound production is efficient and adequate for people’s needs, but the implementation of alternative technologies on a small scale does not seem to threaten the capitalist market system; it may even complement it, precisely because of the capital shortage and the surplus of labor.

2) The demand for collectively managed workplaces and attendant technologies: Worker dissatisfaction is the best predictor of death and disease.35 Such dissatisfaction is correlated with lack of control as well as the boredom of repetitive work. Blumberg points to studies that show that if workers were free to discuss and decide how work is to be done, the result would be a tremendous increase in their sense of well being. At the same time, there is a lot of evidence that under these conditions productivity would actually rise significantly. Bowles and Gintis argue that the only reason that worker’s control over the work process is not implemented is that it would threaten the dominant position of the capitalists.36 Once workers control their own productive activity, they would become intolerant of the remaining vestiges of capitalist domination. Therefore a demand to increase workers’ control is a demand which leads ultimately to socialism.

Workers’ control implies an entirely different technology of production. For example, the regimentation, social isolation, and extreme division of labor which is imposed by a production line is incompatible with a situation in which initiative arises from the workers themselves. From workers’ control, then, there follows an “alternative technology” of production.

Union leaders and radical organizers have not pushed the demand for workers’ control; employers, however, have felt the effects of job dissatisfaction, and have become increasingly interested in programs of “job enrichment” and “worker participation.” Some liberal experiments in job design have stressed the factors of partial worker control and profit sharing, and have in fact increased production, sometimes by up to 40%. The authors of Work in America, far from seeing workers’ control as being a challenge to capitalism, argue that employers who institute workers’ control “will be responding directly to their obligations to shareholders.”37 However, the success of these experiments is destined to be limited. Some have been curtailed when the workers involved, having tasted freedom, demand that employers go all the way, others because employers begin to realize the implications of extending this organization beyond a small group of carefully selected elite workers to the workforce at large. Finally, workers will realize that these enhancements are at base not serious but cosmetic, and that the criterion of profit still rules over human fulfillment.

3) The actual use of technologies of self-sufficient production: If small groups of people could create autonomous cooperative communities which produced their own food, generated their own electricity, heated their homes from the sun, produced their own tools, and in every other way were self-sufficient, these people would have effectively seceded from the market economy. No longer would they have to sell their labor to an employer who extracted a profit from it; and no longer would they have to buy products marked up to assure a retailer a profit. If a sufficient number of people formed such groups, the “economy” as we now know it would disappear: there would be no GNP because goods and services would not be sold; money would become useless.

It is important to note that proposals for social transformation through the formation of such communities must cope with the fact that there is no way that small-scale production can provide the variety and number of goods and services which the international economy now makes available. One can argue that much of. the Gross National Product is useless gadgetry and frivolous services, supported only by artificially stimulated consumption created by massive doses of advertising and media manipulation. The fact is, however, that most people have grown accustomed to certain goods and services, to the extent that they consider them vital necessities and would absolutely refuse to accept a standard of living that did not provide them.

Even the bare necessities of life-food, energy and shelter-can hardly be produced locally as cheaply as they can be bought, assuming that labor has a money value that could be realized in the market. If the aim is to maximize material wealth, these small communities are currently a poor bet.

There are, however, other factors that may go into the balance. The self-governance of work and social life might outweigh material disadvantages. Improvements in the technology of small-scale production could cut costs and raise productivity. At the same time, the costs of energy-intensive large-scale production may rise. It is therefore possible that small-scale production and cooperative consumption could become a broad-based, popular movement that challenges the present economic system. However, it would be impossible to say that this is a likely development.

Further, there are dangers in the concept of self-reliant productive groupings. To a certain extent, the present high-consumption, high-waste system is based on an insidious notion of “self-sufficiency” that is readily exploited. A vague need for human independence and personal achievement is turned into the suburban lifestyle of individual house with individual car, pool, TV and lawnmower. This self-isolation is self-sufficiency only in that the basic consumption unit does not depend on or deal with the other consumption units but deals directly with and is individually exploited by the larger market.

Without larger support systems or a larger sense of solidarity, each consumption unit might be sold its own windmill, rotary tiller, prefab greenhouse and solar heater; radical socialist self-sufficiency will turn into isolated, bourgeois consumption. This insidious notion of self-sufficiency is a motivating force behind much of the alternative technology movement.

Further, even if relatively self-sufficient cooperative production is achieved on the scale of apartment house, city block, housing project or urban neighborhood, there is another possible pitfall: a feeling of isolation on a larger level may occur, in which the community or neighborhood sees itself as set off from, perhaps even in opposition to, not only the ruling classes and the megacorporations, but also society as a whole, decreasing solidarity among working people.

We have examined two aspects of alternative technology: its use as a vision of the future, and its use as a strategy for social change. We are not convinced that alternative technology represents an effective strategy for social change. But we think that providing a vision of the future is important for motivating a movement for social change, and alternative technologies are a crucial part of this vision. The formation of this vision remains as a task for a cooperative effort by scientists and working people.

This article is by Eric Entemann, Fred Gordon, Kathy Greeley, Ray Valdes and Peter Ward, who are members of the Boston SftP chapter’s Alternative Technology Subgroup.

Alternative Technology: Not a Revolutionary Strategy

Chuck Garman, Ken Alper

Introduction

This paper analyzes the failing of alternative technological strategy for social change from a Marxist-Leninist perspective and puts forth a Marxist-Leninist strategy as being historically correct for bringing about changes in social relations. Alternative technology and more generally alternative institutions, which provide a vision to motivate people for change, are not new phenomena. Throughout human history there have been visionaries decrying the baseness and oppression of particular times and calling for a return to some more primitive communal state. A strategy for change based on alternative technology is not sufficient, we believe, for the following reasons: 1) it fails to recognize the fundamental conflict in interests between the working class and the ruling class; 2) it fails to recognize the primacy of the workplace in the process of social change and the necessity of the working class taking state power before basic change in the use of technology can occur; 3) it poses technological gadgets and utopian community as the answer to society’s problems with no need for class struggle.

History of “Alternatives” Strategies

Over the centuries many books on idealistic communistic societies have been written. These have ranged from Moore’s Utopia, Andreae’s Christianopolis, Campanella’s City of the Sun, to Bellamy’s Looking Backward. Visions of nowhere (the meaning of the word “utopia”) were developed and worked out in detail by a number of men, many of whom then tried to put their visions into practice.

Among these was John Wycliffe who argued in 14th century England that communism “ought to be the actual state of society. For God grants everything to the righteous and makes them lords of the earth. But multitudes of men cannot be heirs to the bounties of the earth unless everything is held in common.”38 Wycliffe was preaching at a time when the enclosure of the common lands was beginning and the peasants were in revolt against this oppression.

With the rise of capitalism and increasing exploitation and misery of the masses came the anti-capitalist visionaries. Saint-Simon was one of these early reformers. His proposals included the transfer of industry from private to public ownership, the retention of private property in consumption goods, and the insistence that each shall labor according to his capacity and receive a reward according to services rendered. He believed that the new state should be under the spiritual direction of men of science and that change should be brought about by persuasion, by the written and spoken word, not by means of violence. After Saint-Simon’s death the new faith gained a number of distinguished adherents, engineers, noted professors, writers and other professionals including Buchez, President of the Constituent Assembly of 1830. The movement continued to prosper for a number of years, and the Saint-Simonians made a number of expeditions abroad to promote their faith and to serve people.

By the 1840s, though, the movement started by Saint-Simon was virtually dead. Other Utopians had risen to take his place, each of them with his own particular theories and detailed plans. Fourier developed plans for alternative communities, which Americans like Emerson and Thoreau tried to copy at Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. One of the more influential of these visionaries and reformers was Robert Owen, an English manufacturer. He held that the aim of human society is the greatest happiness of the greatest number and became famous for his paternalistic treatment of his workers at New Lanark, Scotland. He even came to the US and set up a colony at New Harmony, Indiana which failed after three years. His optimism was boundless, and like all utopian socialists, he felt that all that was necessary was to provide an alternative to the baseness of capitalism. At a convention of trade unions and cooperatives in 1833, Owen maintained that the workers would be won over to the truths of cooperation within six months and added: “I will only briefly sketch the outlines of the great revolution in preparation, which will come upon society like a thief in the night.”39

Around this time many cooperatives were started and many of these have failed. Over the century and a half they’ve attempted to compete with capitalism by providing a better alternative. Today there are extensive cooperative movements in most European countries as well as many other countries in the world. In England it is quite extensive and old. Started in the early 1800s, by the 1960s the movement had 12,000,000 members, employing 250,000 people and conducting about 10.8% of the total retail business.40

Today there are new advocates of utopian schemes. Their clarion call is to develop alternative technology or food co-ops, auto repair shops, etc., which people will use to break away from the monopoly capitalist/imperialist system. Another variant is that these alternatives will provide a vision to motivate people to overthrow the system. The alternative institutions strategy for change is based upon the same political assumption as the earlier utopian movements: that class struggle is not necessary and radical change can be brought about by piecemeal efforts.

We believe the central question here is how does the transition from capitalism to socialism take place. In the transition from feudalism to capitalism the capitalist class conquers political power only at the end of a long period during which the economy of capitalism has successfully competed with the economy of feudalism. The advocates of alternative institutions are looking to this model to bring about the transition to socialism.

Alternative Technology Strategy

It is important to differentiate between alternatives themselves and the social philosophy put forth by their adherents. In this article we are not addressing ourselves to the worthiness of an alternative attempt, be it a food co-op, ecology group, collective farm, or commune, etc. Any and all of these may be beneficial for the people involved. What we want to address here is the concept of alternative technology and institutions as a strategy for social change or as a prerequisite for the formation of a “vision” which in tum is necessary for social revolution.

There are a number of arguments against the alternative technology strategy to social change. Alternative technology and institutions often end up isolating people from the mainstream of society. They often start and certainly expand under conditions of· economic crisis. They are carried on by poor, dissatisfied, and frustrated people (including professionals), people who think things can be better, must make ends meet, and/or refuse to act out inhuman social relations. This type of social behavior has long-term drawbacks in that it isolates its participants from the majority. This isolation occurs because the working conditions for such people change. They may not be as oppressed by their work, the managerial and work requirements may be more equal, and the environment may be nice even though the pay may be low. This is especially true in alternative technology done by professionals where the government often foots the bill making one economically comfortable as well as providing what looks like socially beneficial work.

Alternative work is often seen as providing needed public services as well as answers to survival. This situation has three important effects on individuals: 1) alternatives provide a place (escape) for those who see that things are rotten and want to take some action without dealing with the totality of the situation (the necessity for socialist revolution); 2) the public services lessen the crisis for a few, without dealing with or informing them of the real issues (why there is a crisis); 3) the enormous amount of energy poured into such alternatives, many. times for starvation wages, is misdirected for it produces no collective organization capable of taking power. Hence the reality of social life before the crisis becomes reality after the crisis. These characteristics again illustrate the isolating effects of alternative work and especially of alternative technology which has an even lesser emphasis on cooperative work efforts and hence building of organization, than do other alternative institutions.

This isolation is not the intent of any of the people involved (at least not necessarily) but rather as a result of the form and type of actions taken. In fact it is our impression that any person working in an alternative institution or on alternative projects would deny this vehemently. They feel they are trying to help others, work together, develop good things for others. What they do not see are the limitations of their efforts.

The adherents of the alternatives’ strategy believe that they can win in a competitive battle with monopoly capitalism/imperialism. It is the same old strategy developed by the earlier utopian socialists. Provide a better alternative, win over the masses through example and just wait for the capitalists to crumble. We feel this is rather naive, to say the least. The ruling class now owns or controls most of the resources of the country and certainly is not willing to let them or the power associated with them go without a fight. For instance suppose everyone tried to participate in food co-ops. Would they have more control or better food? No! If co-ops significantly increased their size they would become more and more dependent on agribusinesses which could then increase their prices if they wanted, forcing people back to supermarkets to pay higher prices. Depending on local farmers and produce markets works only for a small, isolated minority not for any majority. Much of the farm land in this country is already under corporate control. Another example would be alternative power sources. But again who would produce them? (Assuming they were cheap enough for people to buy, which they aren’t). Does one think that the steel, oil, gas, and electric companies would sit by and let people break up their power monopoly? The prices for raw materials would be made too high or the materials would become unavailable. Again only the few would be able to invest in alternative technology. In fact it is only the few that benefit from David Rockefeller’s daughter’s composting toilet selling at $2000 and good only for those not in apartment buildings. So realistically many people cannot take up alternatives and secondly if they wanted to the present system would see to it that they did not. Alternatives cannot take hold in a monopoly capitalist society.

Also, the government is not going to sit idly by and watch as property relations are attacked and changed. The state is the executive council of the ruling class of a society and our society is no exception. If somehow, alternative technology or institutions were to seriously threaten some sector of the ruling class, you can be sure the state would step in to change the situation. We see no way in which the present ruling class can be dislodged by providing a “better” alternative to people.

The Vision

There are also advocates of alternatives who point out that alternatives are necessary to provide a vision for the future. They realize that better technology cannot change society while the bourgeoisie is still in power, but they put forward the position that alternatives can provide a vision to motivate people to overthrow the ruling class.

What do alternative technologists intend to show in their visions? Other ways of satisfying human needs and developing new cooperative work methods in producing them would seem to be primary. It is hard to imagine what else would be of primary importance besides the poor products we produce and the way people are treated and used by this production scheme. Besides, developments to increase production would only be used by the capitalists to extract more profits.

This view assumes that others don’t have a vision or cannot create one. Let us look for example at the reality surrounding alternative technological work. Most of those people doing alternative technological research enjoy their jobs, probably have at least pleasant working conditions, and many times may even be paid decently. Their view of what is wrong with life is necessarily biased by these factors and hence also their solutions. Alternative technology can be seen as eventually useful for people, providing a way for people to see that better things are possible (vision) and thus acting as a motivation for people to work for change. More strongly than anything else, however, this view puts forth what essentially would be a fine world from the alternative technologist’s point of view. A world where their work would be used to help people and people would have control over their lives. This view is consistent with the class of people holding it: what we call the petit bourgeoisie. They fail to understand the real conditions of the proletariat because they do not share their work situation. The grave mistake that people will take up the struggle and be able to understand and control it without having planned it and without a direct relation to their own gut is committed by those not sick, hungry, or materially deprived. Without this crucial relationship between people and their environment the majority is always left as slaves to the privileged few, this time the alternative technology elite planners.

The vision produced by scientists of alternative technology frequently fails to recognize that what is primary for the working class is their struggle with the bosses. Most workers already understand that their work situation is unpleasant, that products are shoddily built and that the rich are exploiting them. We believe a vision of alternative technology (like windmills) does not motivate workers to struggle against the ruling class; they know of countless examples of capitalist inefficiency and use of technology to exploit.

So we do not disagree with the need of a vision but rather with the type of vision necessary. We see the need for a vision that will enable the working class to take power (revolution) and maintain power (dictatorship of the proletariat) as society is slowly changed (socialism) to eliminate class structure and change production in order to work for everyone’s needs and abilities (communism).