This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Scholars for Dollar$: The Business-Government-University Consulting Network

Adaptation by the editorial committee of a pamphlet by Charles Schwartz

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 1, January 1976, p. 4–9 & 26–29

The following is an adaptation by the editorial committee of a pamphlet — “Academics in Government and Industry” by Charles Schwartz.

800 years ago, at the University of Bologna in Italy, professors had to obtain permission from their students and post bond in order to leave town on private business.1 No such requirements impede the travels of entrepreneurial professors in modern America. While it is widely known that university faculty sometimes hire out their special expertise as private consultants, the full nature and scope of this activity has generally been kept well hidden from public view. While it takes the professor’s time and interest away from teaching and other academic pursuits, and even though consulting fees earned by professors for time spent working elsewhere require no surrender of academic salary, college officials do not look upon consulting as “moonlighting.” Aside from espousing the vague tenet that outside consulting should not interfere with basic teaching commitments, universities generally take a completely laissez faire attitude toward it. In reply to a query about consulting practices, Dr. George Maslach, Provost of the Professional Schools and Colleges of the University of California, Berkeley, said:

I have no knowledge of the extent of outside consulting by faculty and others; I have no knowledge of how many people consult, nor do I know how they have spent their time. There is no indication of how I can obtain this information in any easy way.

The rather startling information presented in this article shows that a large number of academics serve not only as ordinary paid consultants to private industry, but actually sit on the boards of directors of major business corporations. It is proposed that all consulting-like activity by faculty should be treated the same as any other research or academic activity: scrutinized, evaluated in terms of objectives sought, interests served, and publicized and criticized accordingly. It should be another focus of political struggle in academia.

Some Data on Consulting

A survey conducted by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education in 1969 shows how widespread is the practice of faculty outside consulting. Forty-one percent of the faculty surveyed devote between 1 and 10% of their work time to consulting, with or without pay; fourteen percent devote between 11 and 20% of their time; and five percent devote more than 20% of their time. The recipients of paid consulting services were diverse: federal or foreign government (20%); local business, government, schools (18%); national corporations (17%); non-profit foundations (11%); research projects (10%). Only 42% of all the faculty had done no paid consulting during a two-year period. Of all sources of supplemental earnings reported by faculty, consulting was the leading type but other types — such as summer teaching and research, private practice and royalties and lecture fees—were also significant.

An earlier survey, covering the academic year 1961-62, gave data on the outside earnings of faculty broken down according to their academic discipline.2 The overall fraction of faculty having outside earnings was 74%, the highest being in Psychology (85%) and the lowest in Home Economics (44%). The average amount of outside earnings was highest for Law ($5,297) and next highest for Engineering ($3,197); the average for all areas was $2,165.

A reported survey of the Harvard faculty indicated that nearly half of the senior professors had outside incomes that exceeded one-third of their college salaries; and a leading economist at a major Ivy League school was quoted as saying that he charged about $200 a day and added as much as $12,000 a year to his regular income: “I simply need the money,” he explained, “Our nine-month salary is not adequate for the standard of living we like.”3

Information on individual professors’ consulting connections is not publicly available in any systematic form. The standard biographical reference books (Who’s Who for the very elite, or such professional listings as American Men & Women of Science) sometimes list business firms or government agencies for which the individual biographee is a consultant; but these sources, relying as they do on the voluntary contributions of the persons listed, are often incomplete. Numerous cases of academics’ consulting relationships, verified through other sources, are not mentioned in these published biographies.

There are, however, two special kinds of consulting relationships for which one can find published listings of the individuals involved. The first kind covers people who serve on advisory committees to the federal government. According to a law passed by Congress in 1972 (PL 92-463) the President must give an annual report of the activities and membership of the more than 1400 advisory committees that serve the various departments and agencies of the Executive Branch. The first such report was issued in 1973 and it included an index of committee members, arranged by institutional affiliation as well as by name.4 Quoting from the Senate Subcommittee press release that accompanied the publication of this index,

Approximately 24,500 individual positions on advisory committees are identified in the index. The Department of Defense had more representatives on advisory committees — 713 — than any other agency. The university with the most representatives on advisory committees was the University of California (374), followed by Harvard (130) and Columbia (108). Companies with large numbers of representatives on advisory committees include the following: RCA — 93; ITT (and affiliates) — 92; …

The index includes 78 names of U.C. Berkeley faculty and staff serving on a wide variety of government committees, from agriculture and military affairs to science and poetry. (One notes that Provost George Maslach, who had “no knowledge” of faculty consulting activities, is himself listed as a member of two advisory committees in the Department of Defense.) Rich as this index is in information, it should be noted that there are other types of government consultantships which are not covered by the public-disclosure requirements of this law. Also, it appears that this index has not been prepared for years later than 1972.

The second kind of consultantship for which one can find thorough tabulations involves a very special relationship to private industry: being on the board of directors of a sizeable business concern. Dun & Bradstreet’s Million Dollar Directory, published annually and available in many libraries, contains an alphabetized index of directors and top officials in U.S. companies worth over $1 million. The data in this volume is generally one or two years old; and one must take care to verify the identity of persons who are named as directors. This has been done using several published sources: corporation annual reports and stock prospectuses, the biographical books mentioned above, and newspaper items. (The Wall Street Journal has a very useful index for this purpose.) This searching can be a very tedious task: however it has yielded some surprising results.

In Table 1 is presented some data on the University of California (U.C.) showing the faculty and administrators who sit on the boards of directors of sizeable corporations, including some of the coutry’s largest industries. (This is not an exhaustive list since this search was not carried out for the entire faculty, numbering several thousand persons.)

Similarly a survey of the boards of directors of the 130 largest corporations in the U.S., as ranked by Fortune in 1974, shows that academics serve as directors in fully one-half of these giant companies. These findings are presented in Table 2. This listing could readily be extended by further research in this area.

While the job of an ordinary consultant to private business is to help that business solve some particular technical problems, the job of the board of directors is to set and supervise overall company policy, with the express objective of maximizing profit for the company’s shareholders. Thus, the data presented in Tables 1 and 2 suggest that the academic world is integrated into the structure of corporate power at all levels.

Not only do some academics consult for private industry and others serve as advisors to government, but some academics do both. These situations present the most obvious possibilities for traditional conflict-of-interest: for example consulting for industry while advising the government agencies which regulate those industries. Of course the potential conflict between a particular industry or business enterprise and the government in general is a relatively minor one, usually limited to disagreements about standards, product claims, legal requirements, etc. Nevertheless such conflicts can be critical for profits. Thus academic consultants, usually promoted in government advisory circles as experts supposedly independent of special interests, are valuable for business to cultivate, especially when they have intimate knowledge of government operations, policymaking, etc.

Recently, a study of the membership of the two highest science advisory bodies in the federal government found, not surprisingly, that the great majority of the people appointed to these bodies were academics as opposed to people from industry or government agencies. However, what was surprising was that more than half of these academies have significant personal ties to big business, mostly in the form of directorships in large corporations.5

The data given so far whet the appetite and make one eager to find out more about this vast unexplored territory of faculty consulting activities. It is difficult to believe the comment quoted earlier of Provost Maslach (formerly Dean of the School of Engineering) that he has “no knowledge of the extent of outside consulting by faculty.” Rather it seems clear that this subject has a certain taboo associated with it. When a Physics Department chairman was asked about looking into this subject of faculty consulting he declined, referring to it as “a whole can of worms.” When a faculty member suggested that a faculty Senate committee be given the task of reviewing campus policies and practices regarding outside consulting, the response was as follows:

The policy committee has thoroughly discussed the arguments in your letter of April 13, 1973, and finds itself unpersuaded that a useful purpose would be served by Senate surveillance of faculty consulting.

When we considered examples of specific proposals that might emanate from a committee charged with such responsibility, we were unable to imagine situations where positive consequences were plausible. Questions of conflict with University duties are already covered both by Administrative regulations and the Faculty Code of Conduct. The only effective safeguard we can see against the more subtle dangers in consulting is the conscience of the individual faculty member.

Nevertheless a few people, in positions to know what is going on, have been willing to discuss the subject of consulting in at least some detail. Prof. Richard H. Holton, Dean of the School of Business Administration, U.C., Berkeley, in an interview with students looking into consulting activities, expounded as follows:

First I should tell you that I have only a vague notion of how much consulting is done in our school; no records are kept. Right now we’re reevaluating our promotion and consulting policies… We’re looking at the whole reward system that the faculty works under. There is an argument now that faculty in the College of Letters and Sciences have an easier time with promotions than faculty in the professional schools. The greatest emphasis for promotion is on research, with teaching closing fast. Neither University and public service not professional competence is assigned much importance… Not much is done with consulting in the area of professional competence, and faculty don’t keep their files up to date on their consulting activities… Our rule of thumb is that 1 day a week of consulting can be carried without problem. The desirable kind of consulting is the sort that reinforces research and teaching, not competes with it. Consulting can strengthen teaching by providing real case studies and a close look at live management problems… I would guess that perhaps 50%, plus or minus 10%, do some consulting. Most of this would be for business, but many faculty do unpaid work for government and for not-for-profit organizations.

Table 1

SOME UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA ADMINISTRATORS AND FACULTY ON THE BOARDS OF DIRECTORS OF SIZEABLE CORPORATIONS

| Vice Presidents

Chester O. McCorkle, Jr. James B. Kendrick, Jr. Chancellors Daniel G. Aldrich, Jr. (Irvine) William D. McElroy (San Diego) Charles E. Young (Los Angeles) Faculty, Berkeley Luis W. Alvarez (Physics) Melvin Calvin (Chemistry) Richard H. Holton (Business Admin.)

Kenneth S. Pitzer (Chemistry) Glenn T. Seaborg (Chemistry) Edward Teller (Physics) Charles H. Townes (Physics)

Theodore Vermeulen (Chem. Eng.) John R. Whinnery (Elec. Eng.) Faculty, Los Angeles Neil H. Jacoby (Management) Willard F. Libby (Chemistry)

Harold M. Williams (Management) |

-Del Monte Corp.** -Tejon Agricultural Corp.

-Buffums, Inc. -Southern California First National Bank* -lntel Corp.*

-Hewlett-Packard Co.* -Dow Chemical Co.** -Rucker Co.* -Owen-Illinois, Inc.** -Dryfus Third Century Fund -Thermo Electron Corp. -Perkin-Elmer Corp.* -Memorex Corp.* -Granger Associates

-Occidental Petroleum Corp.** -Nuclear Systems, Inc. -Signal Companies, Inc.** |

* Corporations having over $100,000,000 in annual sales or total assets.

**Corporations having over $1,000,000,000 in annual sales or total assets.

Examples of faculty collaboration in the corporate world

The following is a sampling of some of the more celebrated cases of dedication to corporate and/or government service on the part of consulting faculty.

1) When the Federal Trade Commission was trying to get ITT-Continental to clean up its fraudulent advertising, the government’s position was attacked in a series of learned speeches by Professor Yale Brozen, a University of Chicago economist; the Brazen speeches were printed in full by Barron’s, the financial weekly, and full page ads containing the speeches appeared in the New York Times and other newspapers. Hordes of ITT PR men called on financial editors all across the country to acquaint them with Prof. Brazen’s views. It turned out that Brazen was on the payroll of the PR firm handling ITT-Continental’s account and that he was paid for making the proITT speeches.

2) In January, 1975 32 eminent American scientists, all of them Nobel Prize winners, issued a public call for a national energy policy which strongly emphasized nuclear power. Their statement, widely reported, appeared as a 3/4 page ad in the Wall Street Journal (paid for by Middle South Utilities System), and was displayed in full on the editorial page of the San Francisco Chronicle where it listed the signers of the statement and their institutional affiliations. Twenty-six out of the thirty-two were identified with universities and only two with private industry. However a little research established that 14 out of the 26 academic scientists listed have been on the boards of directors of major corporations and 4 others were shown to have served as consultants. The companies to which these academics had connections included several with large investments in energy.6

3) A notorious episode in California concerns the famous oil leaks in the Santa Barbara channel in 1969. The state’s chief deputy attorney general publicly complained that university experts on this problem had refused to testify for the state in its multi-million dollar damage suit against the oil companies, and that petroleum engineers at U.C. campuses indicated fear of losing industry grants and consulting arrangements. One Berkeley professor was quoted as saying, “We train the industry’s engineers and they help us.”7

4) A recent newspaper story revealed that “Equipment and personnel from the University of California’s Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory are now being used in exploratory tests for geothermal steam on a ranch near Calistoga — providing valuable services at no charge to the private interests involved… An official with another company that specializes m geothermal exploration estimated the work would cost as much as $100,000 if it were undertaken by his or other private firms.” The American Metals Climax Co., had made this advantageous arrangement “through a faculty contact.” According to the article, the Dean of Engineering on the campus “declined to comment on the propriety of the arrangement”.8

5) Many academic scientists serving on National Academy of Sciences committees have ties to industry that are difficult for an outsider to detect. Thus a committee that issued a report in 1971 on the biological effects of airborne fluorides was composed entirely of scientists from universities and research laboratories that were seemingly independent of industry influence. It was later revealed that the 4 scientists who had written most of the report had close ties to the aluminum industry, which is a major emitter of fluorides. Some had written publications for the Aluminum Association, received research support from the industry, or testified for the industry in hearings on fluoride standards.

6) In 1965, Dr. Robert H. Ebert was appointed dean of the Harvard Medical School, and in 1969 became a member of the board of directors of Squibb-Beech Nut Corporation, owners of the large drug company E.R. Squibb & Sons. However, some months later following a protest by medical students charging a serious conflict-of-interest between his loyalty to Squibb and his loyalty to the principles of medical practice and teaching, Ebert resigned his directorship. Squibb then gave the vacant seat to Dr. Lewis Thomas, Dean of Yale’s Medical School.

Three years later, Dean Ebert and Dean Thomas appeared together as expert witnesses in a hearing before the Food and Drug Administration, arguing against the banning of one of Squibb’s lucrative drug products. When questioned by the press, a Squibb official stated that neither dean had been paid a special fee for his appearance, since both of them had been retained on the company’s payroll for a number of years. This revelation raised another brief flurry on the Harvard campus; however, when one student was bold enough to propose a university-wide “audit” of faculty consulting, this idea was branded as “McCarthyite” by a prominent administration official.

7) The Jason group is an elite gathering of mostly academic physicists who provide consulting services for the Defense Department. Little is known about Jason however, the publication of the Pentagon Papers revealed their role in the creation and promotion of the “electronic-battlefield” strategy in Vietnam.9 Several Jason members ran for elective office in the American Physical Society, along with the ballots came long lists of their professional achievements and honors. It was later pointed out that none of them had acknowledged their connection with Jason — although several did list their consultantships with the more dovish Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.10

Conflict of interest in the university

The purpose of the modern university is usually proclaimed in high and noble terms: to search for truth, to transmit knowledge and critical skills to students, and to do all this for the betterment of society as a whole. Research and Teaching, the twin primary jobs of the professor, are expected to advance civilized society with both short-term and long-term benefits. We now want to ask how outside consulting is said. to fit into this imaginary scheme. In the basic U.C. policy statement on outside services it is spelled out that this activity by faculty may be justified provided that

- it gives the individual experience and knowledge of value to his teaching or research;

- it is suitable research through. which the individual may make worthy contributions to knowledge; or

- it is appropriate public service.11

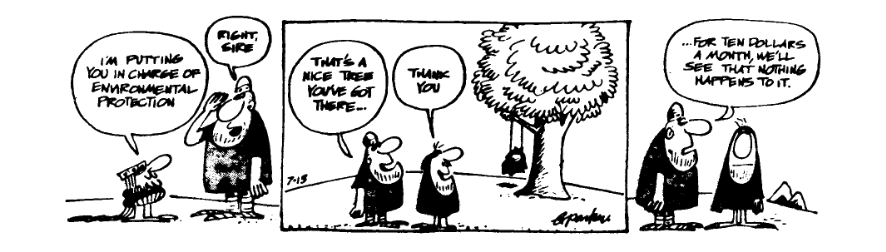

Thus as Dean Holton indicated in his interview, outside consulting is supposed to be an adjunct to the professor’s primary tasks of teaching, research and public service. Certainly there are examples of faculty consulting work that meet this literal standard (using traditional definitions of “value”, “worthy” and “appropriate”) and just as surely there are cases that would fail this test. It is equally clear that university administrators have· no particular desire to meddle in these matters. But what of the more basic conflict of interest for which there are not only no rules but also no admission of its existence? What are the many ways that consulting for private corporations or government agencies influences the content of teaching, directions of research, and allocation of university resources? Ways which have nothing to do with “knowledge”, let alone serving progressive social purposes, but rather with serving the pressing needs of special interests.

The real conflicts-of-interest involved in the practice of outside consulting can thus be identified in the following areas:

1) Teaching: Some professors may be distracted from conscientious teaching because of their frequent involvement in outside enterprise; a commitment to some outside business or government agency might distort the presentation of course material. For example, in the words of one student: “I remember taking a forestry course which repeatedly emphasized how the public should leave the big forestry companies alone and trust them to harvest safely; afterwards I found out that the professor was consulting regularly for the big timber companies.”

2) Research—”the unfettered search for truth”: The outside connections a professor has may readily influence the choice of research topics, especially if the availability of research funding is scarce; and may also have the effect of slanting the research analysis or limiting the types of solutions that may be considered for acknowledged problems. For example, the well documented history of scientific studies on the health hazards faced by asbestos workers shows how an industry can essentially purchase the kind of research it needs for its own uses.12

3) The Role of Universities in General: Students, parents, taxpayers, and legislators are paying professors’ salaries for the same time for which outside income is being earned in the service of private clients. As an illustration, the University of California pays its Vice President, Dr. Chester O. McCorkle, Jr., an annual salary of $53,500 (more than the State pays its Governor); but at the same time Dr. McCorkle is working for two large agribusinesses—Del Monte Corp. and Universal Foods Corp.—as a member of the board of directors of each. ($10,000 a year in director’s fees is typical for a corporation the size of Del Monte.) Thus any citizen can see the contradiction that emerges when the university presents itself as an institution dedicated to the broad public interest while at the same time its faculty is being subsidized to do consulting for the private interests of outside employers, or worse, to help direct entire enterprises. At a time when cut-backs are forcing large scale reductions in hiring, academic programs etc., free handouts to corporations and government continue. It is in this last category that the issue of conflict of interest is most fundamental, because it allows us to look beyond the activities of individual faculty members to focus on the roles of social institutions.

As we might expect, there are common arguments in defence of current consulting practices. First, there is the elitist-pragmatic view, held by many academics, that the ideal of service to the whole society is merely propaganda, (which it is), designed to placate the masses but never taken seriously in practice. The consulting privileges of faculty were obtained during past years when money was plentiful and top rank experts were rare; the universities had no choice but to allow these “big-time-operators” a free reign, and they had no objection in principle. This position deserves no comment.

Apologists, on the other hand, will claim that the participation by academics in the powerful institutions of our society will provide an enlightening influence, and is thus to be praised. (This parallels the arguments advanced in favor of ROTC programs on campus and the justification given by many liberal professors involved in reactionary research programs such as counterinsurgency work for the Pentagon.) The problem is that academics in this position can only work to assist powerful institutions to achieve their goals whatever those goals are; they can try to modify the means (as by suggesting the electronic battlefield alternative to massive bombing in Vietnam) but they must support the ends (military victory) as given.

Another example of this view is the case of Dr. Clifton R. Wharton, Jr., president of Michigan State University, who recently accepted positions on the board of directors of Ford Motor Co. and Burroughs Corp. He announced that he would consider himself to be a “public director” and turned over all his directorship fees to the university. Interviewed about this in Business Week, he said, “I view my role as a person who can exercise the responsibility of the directorship to make a profit, and bring to it a broad social and public concern.”13 Left unsaid is what he will (or can) do when these two stated objectives, corporate profits and social good, come into collision with each other—as they surely do.

Another example of this view is the case of Dr. Clifton R. Wharton, Jr., president of Michigan State University, who recently accepted positions on the board of directors of Ford Motor Co. and Burroughs Corp. He announced that he would consider himself to be a “public director” and turned over all his directorship fees to the university. Interviewed about this in Business Week, he said, “I view my role as a person who can exercise the responsibility of the directorship to make a profit, and bring to it a broad social and public concern.”13 Left unsaid is what he will (or can) do when these two stated objectives, corporate profits and social good, come into collision with each other—as they surely do.

This criticism of consulting is not to say that all consulting by faculty would be abolished in a different social order where private corporate and illegitimate governmental institutions no longer dominate. We should not imagine the university as an ivory tower; it should be interactive, it should serve society. We should struggle for a society in which education, research and production would be much more integrated than at present. Private-property restrictions on knowledge, production-technology and future-research planning would be replaced by public access, discussion and critical evaluation. Consulting would not be an activity of elite, highly privileged individuals who happen to monopolize specific technical knowledge, but rather a communication process involving large numbers of people in all institutions.

A Proposal for Action

While much of the data on faculty consulting presented in this report is new, the broad issues raised are embedded in a rich history of criticism.14 During the 1960’s the campuses of America were hotbeds of protest, against racism, against imperialism, often against the universities themselves, seen as instruments serving those evils. Radicals analyzed the relationship of the university to the larger powers in the society and saw the flow of government dollars into campus research for weapons of war and subtler means of social control, saw the predominance of big business leaders on the boards of trustees or regents that ruled the campuses, saw the calling in of police power to repress student movements that seemed to present any palpable threat to the existing order of things, and saw students, being educated not for the “glory of knowledge” but rather to meet the call for highly trained workers that the corporate system required.

This present study, concentrating on the area of faculty consulting, is intended to illuminate one more aspect of the integrated relationship that exists between the university and the mainstream of American power, showing the outflow of the special expertise of professors into the service of the large corporations and their allied institutions.

The next question we consider concerns action. Extensive public discussion on consulting may itself bring about formal public disclosure of consulting activities. University administrators might decide that it is best for them to institute such a procedure themselves rather than risk too much attention from students, legislators, etc. looking into the cozy arrangements. Under a public disclosure scheme, every faculty or other staff member who engages in outside consulting should make an annual report of this activity for public inspection. It should include the name and location of each person or organization served, the amount of time spent and the compensation received for each consulting job, a brief description of the work done along with copies of any written reports. There is a precedent for this kind of public disclosure in the Freedom of Information Act, which itself resulted from increased public interest and probing into the activities of government bureaucracies.

Examination of consulting activities in detail would have the effect of stigmatizing the most odious kinds of service and forcing much wider accountability than now exists for others. As has happened to some extent with defense contracting, consulting in some areas would become much less frequent. Of course there is always the recourse of seeking faithful consultants at universities not normally inconvenienced by critical debate — as has also happened in many areas of sensitive research work — but this merely reinforces the need to encourage that debate everywhere.

There will naturally be indignant outrage with this sort of program. Claims will be made about the “invasion of privacy” of faculty members, about “where you draw the line” on these kinds of issues, the bureaucratic burden, and “harrassment and embarrassment.” Prof. Luis W. Alvarez, then president of the American Physical Society, explained why a proposal for disclosure of consulting activities was rejected by the Society as follows:

I do not see how one can find a proper cutoff point for information if one does not restrict it to information concerning one’s ability to serve the Physical Society. I think that if I happen to be a member of the Board of Deacons of the local Presbyterian Church, it would be none of the Physical Society’s business. I feel the same way about my directorship on the board of the Hewlett-Packard Company, which is known to most of my friends and associates.15

It doesn’t take much insight to see the difference between a local church and a 500-million dollar electronics manufacturing corporation, as far as significant consulting involvement is concerned.

It is not difficult to predict which groups would oppose the disclosure of consulting activities. The faculty establishment, university administrations, business and government organizations all have benefitted from these traditional arrangements. However, on the other side are students, working people, most consumers and taxpayers in whose interest it would be to see this program aimed at consulting actively pursued. These people are not usually able to hire university “experts” to advance their causes, (however they would usually benefit from publicity if they did so), and in fact are often the victims of big business and government agencies that do make use of the professors’ special talents.

It is not difficult to predict which groups would oppose the disclosure of consulting activities. The faculty establishment, university administrations, business and government organizations all have benefitted from these traditional arrangements. However, on the other side are students, working people, most consumers and taxpayers in whose interest it would be to see this program aimed at consulting actively pursued. These people are not usually able to hire university “experts” to advance their causes, (however they would usually benefit from publicity if they did so), and in fact are often the victims of big business and government agencies that do make use of the professors’ special talents.

Generally it would seem that a political program that addresses current consulting practices should attempt to reveal what really goes on, to more people, and restrict the freedom that private interests and government agencies have in utilizing these resources unencumbered by public discussion. We should also try to show the way toward a different social order where “consulting” (among other things) would serve the people. In exposing and publicizing the consulting situation, it is especially important to reveal the activities of the most elite faculty members, some of whom as participants in the rule of major institutions, have graduated from being servants of the ruling class to being members. We should incorporate critical examination of consulting into broader debates concerning teaching and research goals at every university.

This program can come about only if there is strong and determined effort from students, with some support from faculty, in educating, organizing and agitating. This can go forward in open campus debate, and inside faculty committees where students have a voice. Groups can form to work in individual departments to investigate, generate discussion, pool findings and build pressure for changes. Many students have first-hand experience with the professor-away-consulting syndrome and have extensive knowledge of such acitivities.

Lastly, it should be recognized that this is a systematic problem that can’t be solved with a patch-up job of treating symptoms instead of the real problem—ruling class control of society. Only by making this clear and attacking the full spectrum of problems can we bring about a society in which consulting can be done in the people’s interest.

Charles Schwartz

TABLE 2

ACADEMICS ON THE BOARDS OF DIRECTORS OF THE 30 LARGEST U.S. CORPORATIONS

From a search of the annual reports of the companies listed by Fortune in 1974: the 100 top industrials and the 5 top companies from each of the other 6 categories. Many of the individuals listed below also sit on the boards of other, lesser, corps.

University of California

Melvin Calvin (Prof. Chemistry, Berkeley) — Dow Chemical

Neil H. Jacoby (Prof. Management, Los Angeles) — Occidental Petroleum

Kenneth S. Pitzer (Prof. Chemistry, Berkeley) — Owens-Illinois

Charles H. Townes (Prof. Physics, Berkeley) — General Motors

Harold M. Williams (Dean, Management, Los Angeles) — Signal Companies

University of Michigan

W. J. Cohen (Dean, Education) — Bendix

Morgan Collins (Prof. Emer. Business) — S.S. Kresge

Robben W. Fleming (Pres.) — Chrysler

Paul W. McCracken (Prof. Business) — S.S. Kresge

William E. Stirton (Vice Pres. Emer.) — American Motors

Harvard University

Donald K. David (Prof. Business) — Xerox; Great A&P Tea Co.

Lawrence E. Fouraker (Dean, Business) — RCA; First National City Bank, NY

Jean Mayer (Prof. Nutrition) — Monsanto Chemical

Frederick J. Stare (Prof. Nutrition) — Continental Can

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Howard W. Johnson (Chm.) — Du Pont; J.P. Morgan; John Hancock Life; Champion Int’l.

James R. Killian, Jr. (Hon. Chm.) — General Motors; AT&T

William F. Pounds (Dean, Management) — Sun Oil

Jerome B. Wiesner (Pres.) — Celanese

Columbia University

Courtney C. Brown (Dean, Emer. Business) — Borden; American Electric Power

Grayson Kirk (Pres. Emer.) — IBM; Consolidated Edison

William J. McGill (Pres.) — Texaco; AT&T

California Institute of Technology

Robert F. Bacher (Prof. Physics) -TRW

Harold Brown (Pres.) — IBM

Cornell University

John E. Deitrick (Dean, Emer. Medicine) — Prudential Life

Franklin A. Long (Prof. Chemistry) — Exxon

Duke University

Juanita M. Kreps (Vice Pres.) — J.C. Penney

Terry Sanford (Pres.) — Cities Service

Northwestern University

John A. Barr (Dean, Management) — Esmark

Donald P. Jacobs (Prof. Finance) — Union Oil

Princeton University

Burton G. Malkiel (Prof. Economics) — Prudential Life

Courtland D. Perkins (Prof. Engineering) — American Airlines

Purdue University

Frederick L. Hovde (Pres. Emer.) — General Electric; Inland Steel

Mary Ella Robertson (Prof.) — John Hancock Life

University of Rochester

Robert L. Sproull (Pres.) — United Aircraft

W. Allen Wallis (Chancellor) — Eastman Kodak; Esmark; Metropolitan Life

Stanford University

Arjay Miller (Dean, Business) — Ford

J.E. Wallace Sterlilng (Chancellor) — Shell Oil

Barnard College

Martha E. Peterson (Pres.) — Metropolitan Life

Brown University

Donald F. Hornig (Pres.) — Westinghouse

Bryn Mawr College

Katherine E. McBride (Pres.) — New York Life

California State University

Brage Golding (Pres., San Diego) — Armco Steel

Carnegie Institution of Washington

Caryl P. Haskins (Pres.) — DuPont

Case Institute of Technology

T. Keith Glennan (Pres. Emer.) — Republic Steel

Emory University

E. Garland Herndon, Jr. (Vice Pres.) — Coca-Cola

Hunter College

Robert C. Weaver (Prof. Urban Affairs) — Metropolitan Life

University of Illinois

John Bardeen (Prof. Physics) — Xerox

Illinois Institute of Technology

John T. Rettaliata (Pres. Emer.) — Western Electric; International Harvester

University of Leiden

Ernst H. van der Beugel (Prof. Int’l Relations) — Xerox

Marquette University

Charles W. Miller (Prof. Business) — W.R. Grace

Meharry Medical College

Lloyd C. Elam (Pres.) — Kraftco

Michigan State University

Clifton R. Wharton, Jr. (Pres.) — Ford; Equitable Life

University of Nebraska

Durward B. Varner (PRes.) -Beatrice Foods

New York University

James M. Hester (Pres.) — Union Carbide

Notre Dame University

Theodore H. Hesburgh (Pres.) — Chase Manhattan Bank

Pepperdine University

M. Norvel Young (Chancellor) — Lockheed

University of Pittsburgh

Marina vN. Whitman (Prof. Economics) — Westinghouse; Manufacturers Hanover Trust

Pomona College

David Alexander (Pres.) — Great Western Financial

Rensselaer Polytechnic University

Richard G. Folsom (Pres. Emer.) — American Electric Power; Bendix

Rutgers University

Margery Somers Foster (Dean, Douglass College) — Prudential Life

University of Southern California

Norman H. Topping (Chancellor) — Litton

Syracuse University

William P. Tolley (Chancellor, Emer.) — Colgate Palmolive

Tulane University

Herbert E. Longenecker (Pres.) — CPC International; Equitable Life

Tuskegee Institution

Luther H. Foster (Pres.) — Sears, Roebuck

Virginia Polytechnic Institution

T. Marshall Hahn (Pres.) — Georgia-Pacific

Washington University

William H. Danforth (Chancellor) — Ralston Purina

Wayne State University

Edward L. Cushman (Vice Pres.) — American Motors

Wesleyan University

Edwin D. Etherington (Pres. Emer.) — American Express

Yale University

John Perry Miller (Prof. Economics) — Aetna Life & Casualty

Statistical Summary

68 academic people, from 44 universities, holding 85 directorships, on the boards of 66 corporations.

When these findings are compared with the tabulation given by Ridgeway16 we find that the presence of academics on the boards of these largest corporations has increased by 65% in the seven year interval between these two studies.

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 1 <<

References

- Robert Reinhold, The New York Times, June 18, 1969.

- See Seymour E. Harris, “A Statistical Portrait of Higher Education,” The Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, 1972; McGraw-Hill; page 532.

- Robert Reinhold, op. cit.

- Federal Advisory Committees; First Annual Report of the President to the Congress, including Data on Individual Committees; March 1973; printed for the Committee on Government Operations, Subcommittee on Budgeting, management, and Expenditures, United States Senate, 93rd Congress, 1st Session. Parts 1-4, May 2, 1973; Part 5, Index, January 7, 1974.

- Charles Schwartz, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 1975.

- For details, see Charles Schwartz, Science for the People, May 1975; page 30.

- John Walsh, Science, Vol. 164, April 25, 1969; page 411.

- William Moore, San Francisco Chronicle, June 1, 197 4; page 5.

- See “Science Against the People; The Story of Jason”, Berkeley SESPA, 1972.

- Charles Schwartz, Physics Today, January 1975; page 13.

- “Principles Underlying Regulation No. 4”, University of California Office of the President, June 23, 1958.

- David Kotelchuck, Science for the People, September 1975; page 8.

- Business Week, February 17, 19; page 69.

- Upton Sinclair’s book, cited above is remarkably fresh and relevant despite its age. From recent years there is James Ridgeway’s “The Closed Corporation: American Universities in Crisis” (Random House, New York, 1968) which contains much information pertinent to this present study; and there have been a number of local campus pamphlets: “Who Rules Columbia?”, etc.

- Op. Cit. Charles Schwartz, Physics Today, page 13.

- Upton Sinclair’s book, cited above is remarkably fresh and relevant despite its age. From recent years there is James Ridgeway’s “The Closed Corporation: American Universities in Crisis” (Random House, New York, 1968) which contains much information pertinent to this present study; and there have been a number of local campus pamphlets: “Who Rules Columbia?”, etc.