This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

First Our Land, Now Our Health

by Sandra Spier & Sam Skoog

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 2, September 1974, p. 26 – 29

In 1970, the Department of Defense awarded the University of Minnesota Medical School $88,7251 to continue research begun in 1954 on the biology and epidemiology2 of staphylocci and streptococci, the bacterial agents of the diseases impetigo and nephritis. This investigation involving hundreds of thousands of dollars has been carried on at Red Lake Indian Reservation. The Reservation residents were not treated as patients to be cured of bacterial infection but as a source of experimental data.

In a Symposim recorded in Military Medicine,3 chaired by the principal investigator, Dr. Wannamaker, of the Red Lake studies, the editors state that the findings at Red Lake can be used to predict the risk of development of nephritis among U.S. soldiers in Southeast Asia. In effect, Red Lake was a simulation of the hygienic conditions of a Vietnam battlefield where impetigo is also present. On the grant application for continuation of the Red Lake study,4 the following were listed as reasons for military support:

- Large numbers of soldiers get impetigo.

- Impetigo is endemic5 in the Middle East.

- A difference in susceptibility between races has been noted, the applications of which would be investigated.

Impetigo and Nephritis

Impetigo is a skin disease caused by streptococci bacteria inducing boil-like pustules on the face, legs and other exposed parts of the body, which may itch, bum and bleed. It spreads rapidly, persists unless treated and leads to multiple infection in families. With certain strains of streptococci, impetigo can lead to nephritis, an inflamation of the kidneys, characterized by blood in urine (hematuria) and can lead to kidney failure. Nephritis requires hospitalization. Impetigo is routinely cured with penicillin.

Crowding and low socio-economic conditions appear to influence the spread of impetigo.6 Children are more susceptible to impetigo than are other age groups. Probably due to crowded and unsanitary living conditions, impetigo has been an important cause of illness in wartime, as, for example, troops in the Mekong Delta were commonly disabled by impetigo.

Areas in which widespread impetigo has been studied are Red Lake, Minnesota; Birmingham, Alabama; Trinidad; Lebanon and South Vietnam. The incidence of contracting impetigo seems higher among dark-skinned people but the possible role of racial factors is uncertain. Investigations of racial differences in susceptibility have obvious importance for the U.S. Defense Department in Third World counterinsurgency operations.

Health Care at Red Lake

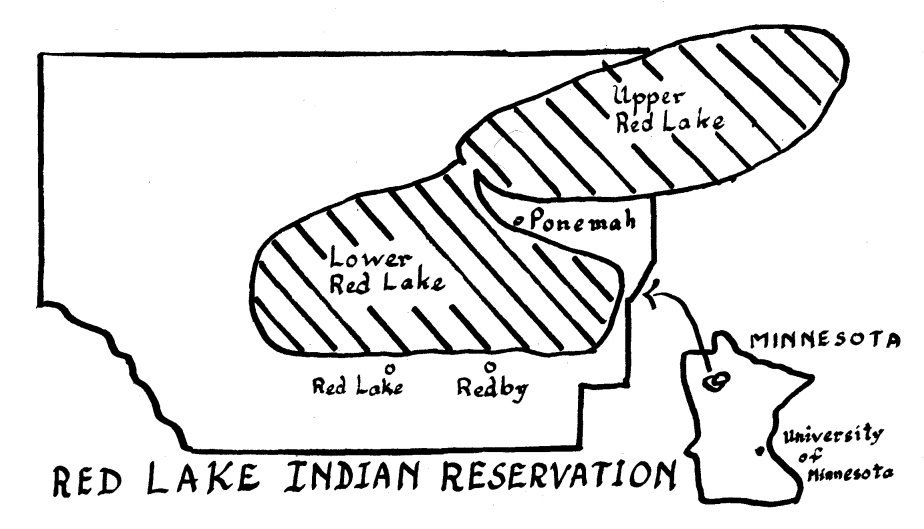

The 900 square mile Reservation of the Chippewa Nation, located in Northwestern Minnesota; comprises approximately 3,000 people. Most of the population live in or nearby the three major towns — Red Lake, Redby and Ponemah. The economy is based on fishing and a small amount of logging. Some jobs are available on the Reservation through work programs instituted by the government such as OEO and HEW.

The medical facilities on the Reservation consist of a hospital and a clinic staffed by two or three Public Health doctors. The Public Health doctors practice on the Reservation in lieu of military service for the three years immediately following their internship. Since the end of the medical draft, the supply of doctors on Reservations is approaching a new low.

Most of the medical problems can be related to the living conditions, such as poor housing, clothing and diet. There are few preventive programs. The average age of death is 42. Diseases of every kind are seen in the Red Lake area. Pneumonia is a winter-long disease; tuberculosis is prevalent. Both impetigo and nephritis have reached epidemic proportions at Red Lake in 1953 and 1966.

Published Red Lake Studies

The following reports are typical of the human impetigo/nephritis experiments conducted on Native Americans at Red Lake, Minnesota:

- After a 1953 epidemic, impetigo at Red Lake was found to be endemic with a high occurence of nephritis. The occurence of nephritis as a consequence of impetigo at Red Lake was first reported in 1954.7 During the epidemic there were 56 cases of nephritis among some 300 cases of impetigo. The report listed the clinical symptoms and the specific type of streptococcal bacteria responsible for the epidemic. It was common for two individuals in the same family to have nephritis.8 The report concluded that penicillin injections were effective in treatment of the disease.Since 1954, most studies proposed to type the streptococcal strain involved in impetigo and nephritis9,10,11,12 and follow the course of the disease.

- A 1970 study13 documents the appearance and the sequential spread of streptococci among the various body sites and their relation to impetigo. Included was epidemiological information on nephritis and impetigo occuring in a family before and after the development of nephritis. A mother and her two 5-year-old twins all developed impetigo and then nephritis during the summer-long study, as reported. The three developed impetigo sores from which M-57 streptococci was isolated (M-57 is one type among a handful of streptococci implicated in nephritis outbreaks as a result of impetigo). The mother of the twins developed nephritis 9 and 12 days before the twins. Not until each had developed nephritis and had been hospitalized was penicillin given. The hospital stay of each was approximately 10 days.In this study the twins and their sisters and brothers, who all had impetigo, were monitored three times per week and left untreated in order to determine the latent period from the time of the first impetigo lesion to the first manifestation of nephritis. However, prompt treatment of infected siblings is recommended14 in families with outbreaks of nephritis.

In this study the investigators seem especially interested in the particular strain of bacteria involved, which presumably justifies (in their minds) the withholding of penicillin from the children and the intrusion on their daily lives three times per week.

- Another recent study, 1971,15 investigated the prophylactic (preventive) effects of penicillin against impetigo. The experiment was done to determine how long after penicillin injections it takes for impetigo to develop in a community harboring impetigo-causing bacteria. In the study, a group of 70 children was divided into two groups, A and B. Group A was given a single injection of penicillin, and group B was given a single injection of saline. Six weeks later, Group B was given the penicillin and group A saline. After each injection, the children went into the community, and the number and time that impetigo was contracted in each group was noted. Results showed that penicillin was an effective prophylactic for 28 days.This type of experimentation with the residents of Red Lake is exploitative because the subjects were not informed of the purpose of the experiment and because the results of the experiment are of no use for the impetigo infections suffered by Red Lake residents. The flare-ups of epidemics were already known to be controlled by wide distribution of penicillin,16 and in the long-term, recurrent, endemic infections (called chronic infections) penicillin cannot be used. Indeed, during long range treatment with penicillin (as with any other antibiotic), people develop resistant bacterial strains; also in a certain percentage of the population penicillin causes a severe allergic reaction.

The rationale behind these experiments can be found in Wannamaker and Dillon, early 1971 article, published in Military Medicine.17 They point out that there was a keen interest of the U.S. military in the efficacy of systematic penicillin therapy, and the lack of such data in early 1971. The symposium from which this article was taken was initiated because of the importance of impetigo as a major cause of disability among servicemen in Southeast Asia. (We have found no such symposium conducted to rid Red Lake Reservation of impetigo and nephritis.)

- Beginning in January, 1966, 100 Native American children in the Headstart program at the Red Lake Reservation were monitored weekly for the presence of streptococci.18 The screening procedures were clinical observations, urine examinations, and culturing of bacteria from nose, throat, and skin lesions. It is not known whether the parents of the children knew the purposes of these examinations.In July of that year, four cases of acute nephritis were detected. The investigators became very interested in the unusual strain of bacteria involved, identical to that of the 1953 epidemics (which had never been studied completely). Surmising an outbreak of nephritis, they undertook a more complete epidemiological study and looked for cases of subclinical nephritis (i.e., cases in which people are not obviously ill) in the Headstart program children. They found 15 such cases with very small amounts of blood in their urine who never showed obvious signs of nephritis and so definite diagnosis of nephritis could not be made. These children were brought to the Unviersity of Minnesota Hospital for a renal biopsy. This can be a painful procedure: the skin is anesthetized around the hip, a long needle apparatus is pushed into the kidney. The kidney sample thus obtained is analyzed for the presence or absence of abnormal kidney tissue. Evidence of kidney damage was found in the 15 children.

All results were tabulated together for a complete epidemilogical picture including data on kidney biopsies, typing of streptococcal strains in impetigo lesions and other body sites; amounts of blood and protein in urine; facial and limb swelling (edema); and hypertension.

A publication19 specifically points out the importance to military medicine of the 1966 studies of the subclinical cases of nephritis (those confirmed only by renal biopsy) including the extent of damage expected from nephritis outbreaks. The Red Lake children population on the other hand did not benefit from the studies. There was no report of treatment. None of the parents had asked for their children to be transported to Minneapolis for kidney biopsies.

Discussion

As discussed in the 1971 Military Medicine article,20 the U.S. military has a deep interest in these studies. Skin infections are a major cause of disability among servicement in Southeast Asia and other places. The type of information in these studies is essential for the control of impetigo in military installations and for prediction of the risk of development of nephritis among such military personnel. Also, the possibility of racial differences in disease susceptibility could be used for military purposes.

These studies are beneficial to another group: the investigators who develop scientific careers by the publication of such studies receiving large sums of grant money. The number of publications and the money a scientist brings into the university are always a consideration in his/her promotion. In all these articles, the sponsorship of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board is acknowledged. No credits are extended to the Native Americans…

The conduct of medical research on Third World peoples is not unique to Red Lake. Other examples are the syphilis studies on Blacks at Tuskegee, Alabama,21 and the hepatitis studies at the Willowbrook State Institution, New York, where low-income people were injected with live hepatitis viruses.22 But we do not need to cite only these blatant examples to show that health care in this country is objectively racist — Third World people consistently receive the worst care while sustaining the highest rate of illness.

At first, it may seem that the exploitation on the Red Lake Reservation is somehow “out there” – morally reprehensible, but not directly bearing on our own lives. Along with this is the idea that when we fight racist practices directed against other peoples, we do it for them, not for ourselves. However, all low and middle income Americans of every race receive inadequate health care, and for the same reasons. Our health needs, like those of Red Lake residents, are sacrificed for the career ambitions of the doctors and the interests of the agencies funding the medical programs. The impetigo study at Red Lake is not merely an atrocity calling for token reparations, but a pointed illustration of the general medical policies that hurt all of us. We see that a fight against the underlying causes of racist health care is in the material interest of all of us.

At first, it may seem that the exploitation on the Red Lake Reservation is somehow “out there” – morally reprehensible, but not directly bearing on our own lives. Along with this is the idea that when we fight racist practices directed against other peoples, we do it for them, not for ourselves. However, all low and middle income Americans of every race receive inadequate health care, and for the same reasons. Our health needs, like those of Red Lake residents, are sacrificed for the career ambitions of the doctors and the interests of the agencies funding the medical programs. The impetigo study at Red Lake is not merely an atrocity calling for token reparations, but a pointed illustration of the general medical policies that hurt all of us. We see that a fight against the underlying causes of racist health care is in the material interest of all of us.

The Minnesota chapters of Science for the People and the Committee Against Racism [CAR] worked together in the preparation of this report. CAR is a recently formed national organization predicated on the assertion that racism hurts all of us, including whites, and that we must unite in a multiracial struggle whose outcome is crucial to the majority of people in our country. We are carrying out further work on this issue.

Further information about the CAR project on Red Lake can be obtained by writing:

CAR, Minneapolis Chapter

c/o E.C.

1507 University Ave. S.E.

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55414

References

- Contract number DADA 17-70-C0081 and DADA 17-70-C0082.

- Epidemiology is the science investigating the incidence, distribution and control of a disease in a population.

- Wannamaker, L.W.; and Dillon, H.C.: Skin infections and acute glomerulonephritis: Report of a symposium. Military Medicine 136: 122-127, 1971.

- On file at the University of Minnesota Research Accounting Office

- Endemic means prevalent in a particular geographic region.

- Wanamaker, L.W.: Differences between Streptococcal infections of the throat and of the skin. New Eng J Med 282: 23-30, 1970.

- Kleinman, H.: Epidemic acute glomerulonephritis at Red Lake. Minnesota Medicine 37: 479-483, 1954.

- Kleinman, H.: Epidemic acute glomerulonephritis at Red Lake. Minnesota Medicine 37: 479-483, 1954.

- Anthony, B.F., Perlman, L.V., and Wannamaker, L.W.: Skin infections and acute nephritis in American Indian children. Ped 39: 263-279, 1967.

- Dudding, B.A., Burnett, J.W., and Chapman, S.S., et al.: The role of normal skin in the spread of streptococcal pyoderma. J Hyg (Camb) 68: 19-28, 1970.

- Anthony, B.F., Kaplan, E.L., Chapman, S.S., Quie, P.G., and Wannamaker, L.W.: Epidemic acute nephritis with reappearance of type 49 streptococcus. Lancet 2: 787-790, Oct 14, 1967.

- Kaplan, E.L., Anthony, B.F., Chapman, S.S., et al: Epidemic acute glomerulonephritis associated with type 49 streptococcal pyoderma. I. Clinical and laboratory findings. Am J Med 48: 9-27, 1970.

- Ferrieri, P.F., Dejani, A.S., Chapman, S.S., Jensen, J.B., ·and Wannamaker, L.W.: Appearance of nephritis associated ‘with type 57 streptococcal impetigo in North America. New Eng J Med 283: 832-836, 1970.

- Dillon, H.C.: The treatment of streptococcal skin infections. J Ped 76, No. 5: 676-684, 1970.

- Unpublished, conducted summer 1971.

- Kleinman, H.: Epidemic acute glomerulonephritis at Red Lake. Minnesota Medicine 37: 479-483, 1954.

- Wannamaker, L.W.; and Dillon, H.C.: Skin infections and acute glomerulonephritis: Report of a symposium. Military Medicine 136: 122-127, 1971.

- Anthony, B.F., Kaplan, E.L., Chapman, S.S., Quie, P.G., and Wannamaker, L.W.: Epidemic acute nephritis with reappearance of type 49 streptococcus. Lancet 2: 787-790, Oct 14, 1967.

- Wannamaker, L.W.; and Dillon, H.C.: Skin infections and acute glomerulonephritis: Report of a symposium. Military Medicine 136: 122-127, 1971.

- Wannamaker, L.W.; and Dillon, H.C.: Skin infections and acute glomerulonephritis: Report of a symposium. Military Medicine 136: 122-127, 1971.

- “Matter of morality; study on effects of untreated syphilis,” Time 100:54, Aug. 7, 1972.

- Symposium sponsored by the Student Council of New .York University School of Medicine, May 4, 1972, “Ethical Issues in Human Experimentation: The Case of Willowbrook State Hospital Research.”