This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Review: Complaints and Disorders — The Sexual Politics of Sickness

Reprinted from Rough Times/Liberation News Service (LNS)

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 4, July 1974, p. 20 – 21

Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness is available for $1.50 from the Feminist Press, Box 334, Old Westbury, N.Y. 11568.

Reprinted from Rough Times/LNS

Medical science has been one of the most powerful sources of sexist ideology in our culture. Justifications for sexual discrimination must ultimately rest on the one thing that differentiates women from men: their bodies. Theories of male superiority ultimately rest on biology.

Medicine stands between biology and social policy, between the ‘mysterious’ world of the laboratory and everyday life. It makes public interpretations of biological theory; it dispenses the medical fruits of scientific advances… Biology traces the origins of disease, doctors pass judgement on who is sick and who is well.

— from Complaints and Disorders

Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness is a new pamphlet by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, the authors of Witches, Midwives and Nurses. Both are published by the Feminist Press in Old Westbury, New York.

While Witches, Midwives and Nurses offers an introduction to the history of women healers, and focuses on the takeover of medicine by male professionals in the nineteenth century, Complaints and Disorders deals with the medical system and ideology from 1865 to 1920 and how it applied to women.

The authors focus separately on women of the upper and upper-middle class, and on working-class women. And they are clearer about the effects of the medical system as it applied to affluent women [probably because wealthy women were more directly affected by the medical system]. In addition, Ehrenreich and English explore the ambiguities of the early public health reform movements directed—often by wealthy women—at the poor.

The following is a summary-review of Complaints and Disorders mostly excerpted directly from the 94-page pamphlet.

* * *

Affluent women lived lives of enforced leisure. The majority of upper and upper-middle class women had little chance to make independent lives for themselves; they were financially at the mercy of their husbands and fathers. They had to accept their roles—outwardly at least—and remain dutifully housebound, white-gloved and ornamental.

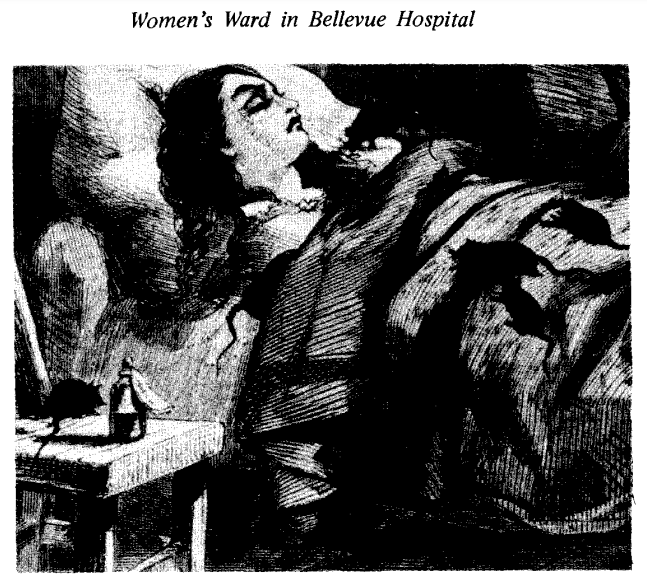

This boredom and confinement fostered a cult of ‘female invalidism’ that began in the mid-nineteenth century and didn’t fade until the late 1910’s. Sickness was an integral part of upper and upper-middle class female culture and made these women dependent for their very survival on both doctor and husband.

Women at that time did in fact face certain risks that men did not. Childbearing, for instance, was much more dangerous. In 1915, the first year for which national figures were available, 61 women died for every 10,000 live babies born, as compared to 2 per 10,000 today. Maternal mortality rates were no doubt even higher during the nineteenth century and without contraception, a woman could expect to face the risks of childbirth repeatedly.

In 1900, there were 173 doctors per 100,000 population in the United States, compared to 50 per 100,000 today. It was in the interest of doctors to cultivate the illnesses of their wealthy patients with frequent home visits and drawn-out treatments. Some women saw through this, and Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi wrote in 1895:

“I think, finally, it is the increased attention paid to women, and especially in their new function as lucrative patients, scarcely imagined a hundred years ago, that we find explanation of much of the ill health among women, freshly discovered today.”

The underlying medical theory of women’s weakness at that time rested on what doctors considered the most basic physiological law: ‘conservation of energy.’ According to the first postulate of this theory, each human body contained a set quantity of energy that was directed from one organ or function to another. This meant that you could develop an organ or ability only by drawing energy away from the parts not being developed.

The second postulate of this theory—that reproductivity was central to a woman’s biological life—gave the reproductive organs almost total command of the whole woman.

Since reproduction was woman’s purpose in life, doctors agreed that women should concentrate their physical energy inward, toward the womb. Doctors and educators were quick to draw the obvious conclusion that, for women, higher education would be physically dangerous. Too much development of the brain, they counseled, would atrophy the uterus. In addition, doctors found uterine and ovarian “disorders” behind almost every female complaint.

Treatments were aimed at altering female behavior. One, used to treat many problems diagnosed as “nervous disorders,” was based on isolation and uninterrupted rest. Passivity was the main prescription, along with warm baths, cool baths, abstinence from animal foods and spices, and indulgence in milk and puddings and cereals. As a Dr. Dirix wrote, “all forms of mental excitement were to be perseveringly guarded against.”

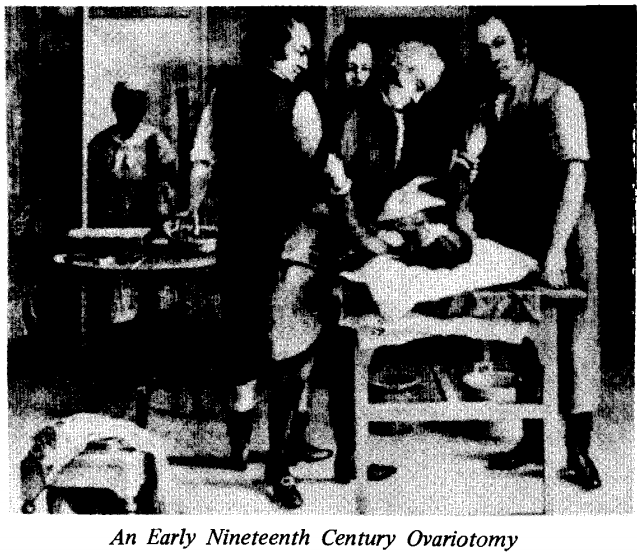

Doctors also took the surgical approach. Since a woman’s entire personality was supposedly dominated by her reproductive organs, then gynecological surgery was the most logical solution to any problem. Removal of the clitoris was practiced and more widely, removal of the ovaries or “female castration.”

Patients were often brought in by their husbands, who complained of their unruly behavior. When returned to their husbands, they were “tractible, orderly, industrious and cleanly,” according to Dr. Robert Battey of Rome, Georgia, in 1872. Of course the very threat of surgery was probably enough to bring many women into line. In fact the medical attention directed at these women amounted to what may have been a very effective surveillance system. Doctors were in a position to detect the first signs of rebelliousness, and to interpret them as symptoms of a “disease” which had t be “cured.”

Working class women were in an entirely different situation. Crowded, poor living conditions were fertile breeding ground for typhoid, yellow fever, TB, cholera, and diphtheria. While sickness, exhaustion and injury were routine in the life of the working class woman, a day’s absence from work could cost a woman her job.

Two women who worked in the garment industry recall, ”We only went from bed to work and from work to bed again… and sometimes if we sat up a little while at home we were so tired we could not speak to the rest and we hardly knew what we were talking about. And still, there was nothing for us but bed and machine.”

While there was no great public outcry about the health of poor women, there was a great deal of upper and upper-middle class concern about what the poor were doing to the “health” of the cities. Disease was invariably seen as foreign in origin, imported on immigrant ships and bred in immigrant slums. While it was true that the rates of infectious diseases were higher among the poor, the affluent frequently used a fear of germs to express their fear of the poor.

Working-class women, often employed as house-hold servants in the homes of the rich, were regarded as potentially “sickening.” “If anything was missing, like a piece of silverwere, servants must have taken it. If anyone in the family got sick, you naturally suspected the servants of carrying something,” according to one survivor of the early twentieth century.

As the health of the poor posed a threat to the upper classes, the public health movement and birth control movement arose, both drawing heavily on the energies of upper and upper-middle class women. Although these movements obviously brought progressive achievements, both mobilized large numbers of wealthy women in a way which solidified their relationship to working class women—not as sisters, but as uplifters.

The issue of health—female health and family health—which potentially could have united women of different classes, now divided them into “reformers” on the one side and “problems” on the other. Upper-middle class women did not turn against the medical profession that had imprisoned them and rejected poor women. They did not unite with poor women to create a movement which could demand a single standard of health care for all women. Instead they allied themselves with doctors against the poor.

Complaints and Disorders ends with some thoughts on the situation today. ”We can only marvel at the endless plasticity of a medical ‘science’ that can adjust its theories for age, sex or social class depending on the needs of the time. …What is amazing about medical ‘science’ as it relates to women is that the theories change so neatly to fit the needs of the dominant, male ideology.”

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 4 <<