This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Politics of Health

by Multiple Authors

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 4, July 1974, p. 6 – 19

Politics of Health

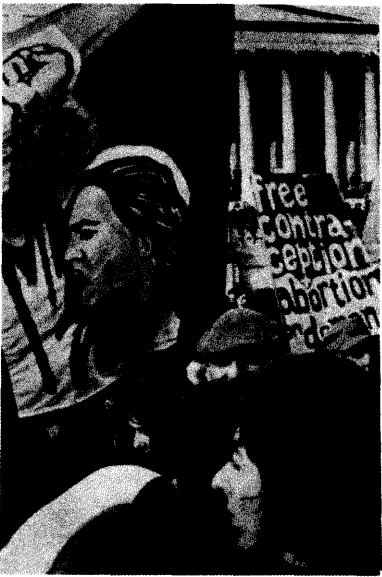

The health care system and the industrial health and safety conditions in America can only be described as institutional murder. In recent years radicals have worked to create alternatives to present health structures, to confront and expose the capitalist health system, and to organize around health and safety issues in the workplace. All of these struggles serve to improve people’s day-to-day situations and politically educate those involved. For those of us who see these efforts as part of a broader struggle for socialism in this country, we must ask how these efforts are helping to build this broader struggle. The following articles “The Emma Goldman Women’s Health Clinic“, “Midwest Workers Fight for Health and Safety“, and “How to Look at Your Plant” present important ongoing struggles.

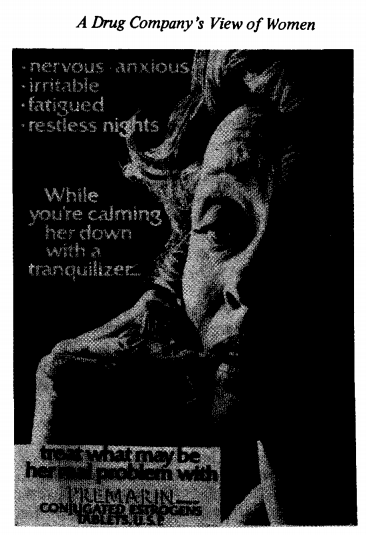

The first article describes the Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center, which was begun two years ago in north side Chicago. The Emma Goldman Collective, which stresses the importance of individual responsibility and self-reliance, created the clinic in the belief that women would not have decent health care until they took care of it for themselves. The members of the Emma Goldman Collective, whose politics is anarchist, deal with the immediate health problems of women, but we, as socialists, believe that this is not an adequate solution to the problem. We believe that the central problem of health care in America is that the major facilities—hospitals, drug companies, health insurance—are controlled by a wealthy elite which profits by them. Those of us who work in community health clinics must be aware of the need not only to help provide health care, but to expose and confront the inadequacies of the capitalist health system. It is only after this system has been overthrown that a health care system truly by and for the people can be built.

“How to Look at Your Plant” (page 17) is excerpted from a handbook for workers which describes how to detect and deal with health and safety hazards in the workplace. “Midwest Workers Fight for Health and Safety” (page 12), a speech by Carl Carlson, is a clear and forceful appeal to workers to organize and fight against dangerous working conditions. As his speech illustrates, working people in this country have been compelled to sell not only their labor, but their very lives. The question is, whether these struggles around occupational health and safety advance the political consciousness and militancy of the working class.

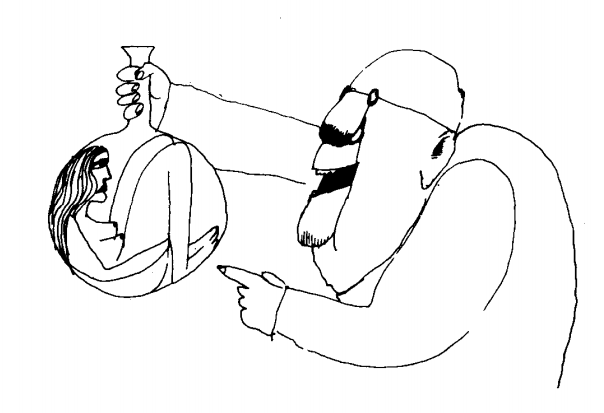

Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center

One day an inspector made his way into the clinic, flashing his badge. “Who’s this here Emma Goldman?” he wanted to know. But he wasn’t really interested in hearing of courageous Emma’s deportation for draft resistance, or of her nursing and midwifery skills. When he heard that she’d died in 1940 he wrote “Now deceased” on his form. You’re wrong, Mr. Inspector. Emma Goldman is alive and well and living in Chicago.1

The Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center is located at 1317 W. Loyola (Chicago). It offers routine gynecological care by feminist paramedics. Donations are strictly voluntary. Clinic hours: Monday, 7–9 p.m.; Saturday, 10–2 p.m.

A Short History

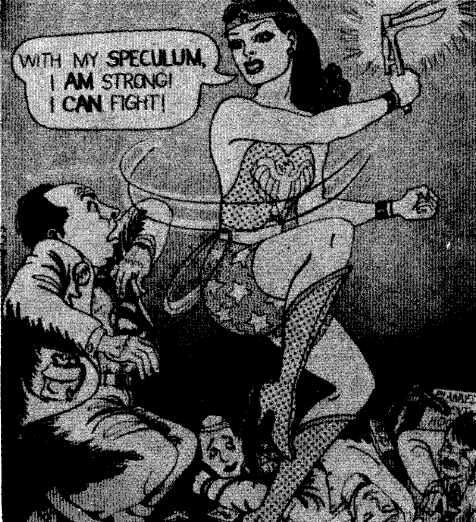

“Health” was a big word in the women’s movement in the beginning of 1973. “Bodies” classes were spreading the doctrine of self-help—teaching that a woman had the right to control over her own body. The Boston Women’s Health Collective’s 40¢-newsprint-edition of Our Bodies, Our Selves2 was our bible, and the Supreme Court abortion ruling our first solid taste of victory. The legalization of abortion freed a lot of energy in the women’s health field and provided the breathing space in which ideas about a new kind of health care could be given form and life.

In Chicago a four-year-old feminist paramedic abortion service (JANE) was disbanded and a court case against some of its members was dropped. Thus, people, skill, and equipment from the service as well as the money and interest which had been mobilized for the defense were available for other tasks.

In April 1973 some women from JANE, some from Southside Pregnancy Testing [see box], and others began to hold meetings to plan the opening of a women’s health clinic. Ultimately the clinic drew women from a wide variety of backgrounds—some brought skills as nurses, pre-med or nursing students; some from working in other free or women’s clinics; and some had no previous medical experience at all.

Meetings were held by a constantly diversifying membership of 20 to 30 women for nearly a year before a place was found and the clinic became a reality. It was not until the clinic opened in Jan. ’74, that the distinctions between old and new people began to be blurred and the group emerged as a working unit. We had a long time to get to know each other and to work out ways of dealing with our differences while we were getting it together.

With time, a sense of what we consider most important about ourselves has emerged. The following is a summary.

Purposes of the Emma Goldman Clinic

To enact and convey to others a strong optimism about our physical and social potential as women.

To provide routine and unmysterious health-care which respects and encourages a person’s right to make informed decisions about her own health needs.

To involve women in self-help, and in the collection and interpretation of their own medical histories.

To demonstrate that health care can be dignified and to arm women with the knowledge that they can demand such treatment from the health establishment.

To provide services to women who might otherwise not get them.

To be a collective—a source of joy, strength, and power among ourselves and for the women who use the clinic.

JANEJane, a Chicago women’s liberation abortion service, …”that proved by four years experience that included performing more than 12,000 illegal abortions, that abortions can be performed safely, humanely and very inexpensively by nonprofessional paramedics working under often primative conditions.” (from “The Most Remarkable Abortion Story Ever Told”, Hyde-Park Kenwood Voices (Chicago) June 1973) The service functioned from about mid 1969 to April 1973. It was initially a referral service for abortionists, and then achieved partial independence thru special arrangements with one abortionist, which began a slow process of dropping the price and raising the educational status of the counselors. When the service finally closed, the fees had been reduced to low levels only possible because the abortions were being performed by trained paramedics drawn from the ranks of the counselors. Because many of the women affiliated with Jane were equally concerned with improving the quality of women’s health care in general, and the level of knowledge about their own bodies among women, as they were with providing safe, inexpensive abortions, they sponsored self-help clinics for women from time to time, offering free pap smears, v.d. testing, self examination, etc. |

PREGNANCY TESTINGIn 1970, women from the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union set out to build a city-wide movement around health-related issues.. Alice Hamilton Women’s Health Center was the vision, a clinic which would provide free or at cost medical care for women and children; educate women in nursing skills laboratory skills and medical records, and offer courses that would be generally useful for women (Nutrition, prepared childbirth, etc.) Lack of funds prevented the simultaneous opening of all aspects of the clinic and instead services were phased in as they became feasible. Courses on Women and Their Bodies, and Prepared Childbirth; and Pregnancy Testing appeared at locations around Chicago. Pregnancy testing has become a self-perpetuating, self-supporting operation with the skill passed on from one group of paramedics trained in the women’s movement to another. Both pregnancy testing and Bodies courses have achieved the status of women’s movement traditions in Chicago, and probably in most other parts of the U.S. as well, and are part of the program of most women’s liberation organizations. |

How do we work?

Emma Goldman is a collective. At the present time there are about 40 of us. We believe in decision-making by consensus. In practice, this often means “consensus by default”—the ones who care enough about something, do it in a way that is more or less acceptable to all.

Emma Goldman is a collective. At the present time there are about 40 of us. We believe in decision-making by consensus. In practice, this often means “consensus by default”—the ones who care enough about something, do it in a way that is more or less acceptable to all.

We hold clinic two times a week, and are thinking about adding a third time. We see ten to twenty women and receive $20–$30 in donations each time. Skills are transferred during clinic by a “team” arrangement in which skilled and unskilled work together. Groups of 6 or 7 meet weekly in bodies classes (sometimes with skilled outsiders) to increase the group’s total knowledge. Though we are in the process of developing orientation procedures, no formal mechanism insures that a person will learn all the basic skills, nor is there yet a clear sense of exactly what these skills are. The group has avoided structuring tasks, insisting that members take individual responsibility for doing what needs to be done. More structure is developing as our responsibilities increase, but the credo of individual responsibility remains central. Anarchist Emma would probably feel comfortable with us. We know, as she did, that women will not have decent health care until they take it for themselves.

We have full membership meetings once a week, varying the place so that the full burden of travel doesn’t always fall on the same people. Transportation difficulties create divisions which we struggle against with limited success. The groups’ use of social gathering to cement feelings of solidarity outside the meetings has to struggle against the realities of geography and a poor public transit system.

Our meetings are loud, lively and frequently emotionally charged. Feelings are often discussed and arguments are often heated. Healing meetings follow angry ones and people take it on themselves to “follow up” on anyone who might have been hurt at a meeting. Meetings in people’s houses tend to be friendlier than meetings at the clinic.

Our meetings are loud, lively and frequently emotionally charged. Feelings are often discussed and arguments are often heated. Healing meetings follow angry ones and people take it on themselves to “follow up” on anyone who might have been hurt at a meeting. Meetings in people’s houses tend to be friendlier than meetings at the clinic.

The way we work is predicated on a high degree of trust in each other’s judgment. We seem pretty good at routine self-criticism, but we haven’t yet figured out how to deal with the individual who consistently makes serious mistakes.

The clinic operates out of a brightly-painted storefront in a heterogeneous neighborhood on Chicago’s northside. It is near an ‘L’-stop, so we are accessible from other parts of the city. We advertise in a citywide free weekly and get referrals from other women’s groups in the city. We won’t do any more advertising until we train more people. We are handling all that we feel we can right now.

We pay for some of our expendable materials and we get some donated. Nearly all our equipment was donated. We are seeking a free-supply relationship with a city hospital, such as Benito Juarez, a Chicano clinic, demonstrated for and won several years ago. (They are thus able to maintain a free pharmacy.) We are also looking for funding, since our present resources will probably run out in six months or so.

Our only problem with the community so far arose over the mistaken belief that we do abortions. (Our sign said “abortion counselling”.) On opening night a contingent of Right-to-Lifers raised a big fuss. Shortly afterwards several city agencies came around checking out “complaints”.

During the period of planning, the collective was not successful at recruiting doctors, although some did express interest in working with us after we became operational. Ideally, our doctors will be co-equal members of the collective, sharing and learning skills with the rest of us and drawing on the power generated by women working well together. So far, the women doctors that we have located have not become this deeply involved. With time, we hope to work this out.

Working Out Our Differences

There have been several big disputes whose resolution has been critical to the survival and nature of the clinic.

Lesbianism. When the group rejected the possibility of sharing a building with some Lesbian-feminist groups last summer, hostility between Lesbians and straights surfaced. Several of the Lesbians decided that the group could not be supportive for them and left. The straight women of the group tried to reassure the remaining Lesbians that they considered it important that the group represent gay interests, but that was not enough. Nobody wanted to be the clinic’s “token Lesbian”. It took a lot of emotional effort, but the honesty shown and the support offered made it possible for some to stay and for others to return.

Men. We are a clinic by and for women, offering no services to men alone. However, when a woman indicates a desire to be counselled with a man, we do so. Recently a decision was made to restrict men to the outer rooms. The decision was a sensible and easy compromise between total exclusion and no restriction, since respect for a woman’s right to be treated with a friend of her choice eliminated one extreme and the problem of congestion eliminated the other. It was clear, however, when the subject came up, that differences of opinion ran deep, and that the broad issue of the clinic’s proper relations with men is far from settled.

Money. The clinic was formed in order to bring into existence a new kind of health service, then unavailable at any price. Doing a health clinic for “Chicago’s needy” could have been a big charity trip for the largely middle class women of the group. What the clinic was trying to be would be useful and important to each of us directly. Many feared that money worries could close the clinic, or at least drain away precious energy from the main business of actualizing this new concept of health care.

Others felt that the clinic would not be worth doing unless it was free. After months of dispute, consensus was realized in the decision to operate on a voluntary donation basis, with a posted list of our expendable costs serving as a guideline. (Also as a tacit commentary on the usual medical fee rip-off.) Our collections, in practice, about match the income that we would have received for the sums we considered charging, but the donations are unevenly distributed, from nothing to $10 or $15.

In Sum

In Sum

It is a continuous source of excitement that a group with such different opinions and styles can work together, and so successfully. The energy, satisfaction and strength we derive from working together is tremendous. We have a history of working out our problems which gives us enormous enthusiasm for doing what remains to be done. We are already outgrowing our space.

The future? Two, three, many Emma Goldman’s!

— Arlene Ash with a lot of help from her friends

MIDWEST WORKERS FIGHT FOR HEALTH AND SAFETY

The following speech was given on March 16 by Carl Carlson, a Chicago worker, to a gathering of workers, union leaders, doctors, scientists and radicals in Madison, Wisconsin. The event was a “Workers’ Forum on Safety and Health” which Science for the People had helped organize. On the program were speeches by union leaders and university experts on occupational health, but Carlson’s speech was clearly the most exciting moment of this forum, which we hoped would lead to an organization to aid Madison workers in their fight for healthy working conditions.

The idea for this organization came to us from Chicago, where CACOSH (Chicago Area Committee on Occupational Safety and Health) has been carrying on this kind of program since 1972. CACOSH has been providing Chicago workers and their unions with the scientific, legal and medical skills needed to identify hazardous working conditions and to force their bosses to remove them.

Inspired by the CACOSH example, various people in Madison have wanted to form an occupational health group. To get started, we organized the occupational health forum, and one of the first speakers we invited was the CACOSH president, Carl Carlson. We also asked many local labor leaders to speak to the forum or to publicize it among their members. Some of the union representatives, especially from industrial unions, were enthusiastic about our ideas. Another important ingredient was the publicity given to the occupational health issue by We The People, a radical newspaper written for local workers.

About fifty people came to the occupational health forum, and out of it came a permanent action group. A group of workers, union representatives and technical people have meetings every other week, and we have already begun work on the health problems in a foundry, the phone company, a meat packing plant and a plastics fabricating shop. The enthusiastic co-operation we have gotten from the workers tells us that we are working on an important issue.

— Joe Bowman

First of all, I’d like to get one thing straight—I’m not an expert. I don’t profess to be. I got involved in safety work quite by accident when I was working for the International Harvester Company, where I’ve been employed now for twenty-seven years. I got appointed to the accident and safety committee and took part in an investigation of four fatal accidents in our plant.

As I investigated these accidents, it became clear that all four were toally preventable. But, of course, they weren’t prevented; they happened, and the people died. The first fellow was boiled alive in a large tank of “oakite” we were using for stripping parts. Nobody knows whether he drowned or was boiled alive. Two men were crushed under tractors, and the last man was cut in half when a flywheel came apart on an engine under test. He survived for about two days before he died.

Inadequate Protection For Workers

As I said before, my getting into safety work was quite by accident. But soon after I did, I learned of the total inadequacy of protection for workers. The Walsh-Healy Act, which was passed in 1936, established a lot of safety standards. But the only way of enforcing the law was the threat that, if the company had more than $5,000 worth of contracts with the government, the government might take the contracts away if the company didn’t obey the standards. But I know of no such action whereby any department of government took any contracts away. We had the federal people come out to our plant twice. They inspected the plant and gave the company a laundry list of things that should be corrected. But there was no enforcement, and some of those hazards still exist today.

Now we have the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSHA). The purpose of the act, as stated in its preamble, is: ”To assure, so far as possible, every working man and woman in the nation safe and healthful working conditions, and to preserve our human resources.” Now that’s a very simple statement, and very profound. Obviously, if that preamble were enforced, we wouldn’t have need for all of these laws and lawsuits and everything else.

I think the reason for the law is something we should recognize. The politicians were aware of the horrible state of safety conditions in the country. The fact was that the total number of safety inspectors for corporations and factories in the country prior to OSHA was one-thousand. And most of these people were toally unqualified to do their job—just political hacks who got a job because they were somebody’s brother-in-law.

There are fifteen thousand deaths recorded annually, and more than 1.2 million work-related illnesses and accidents. A Presidental Commission has estimated that more than 100,000 persons die each year as the result of long-range effects of unsafe working conditions.

Law’n Order For Corporations

Unfortunately, a lot of problems stand between the enactment of the OSHA law and actually getting some things done. One of the big problems is the lawlessness of the corporations that we deal with, and the fact that violations usually result in only the lightest of penalties. To show you how things work, take the Sherman AntiTrust Act. This act was passed in 1890, and like OSHA, provides for criminal penalties. Neverless, in eighty-three years, and in spite of a large number of convictions, if you take the total time spent by corporation people in jail as a result of all these convictions, it’s less than two years. Now that’s not a very good record.

As an example, in 1967 a Convair 580 plane crashed and thirty-eight people were killed. The government agency investigating the crash found out that the Allison Division of General Motors had knowingly and deliberately supplied faulty propellers to that plane. They knew they were bad, and the total fine for General Motors was eight thousand dollars.

In 1964, a drug company was found to have submitted false data to the Food and Drug Administration about an anti-cholesterol type of drug. It was put on the market, and after a few thousand customers had reactions—some got cataracts, some had loss of hair, some had severe skin reactions—they finally removed the drug from the market. The case went to court and was tried. Now the company made eighteen million dollars from the sale of that drug, but here again, the total fine for the company was eighty thousand dollars. And the three company executives who were responsible for submitting the false data, all got suspended sentences.

Outlaw Corporations

Now, to show you the kind of corporations we have, in the last forty-five years, 60% of the 70 largest corporations in this country have been convicted an average of 4 times each for criminal offenses of violation of the law. And all seventy corporations have had civil convictions, an average of 14 each. There are very few street criminals who can come anywhere near that kind of record!

In 1961, the Harvard Business Review, did a survey of business ethics. The magazine submitted a questionnaire to a lot of businessmen, and of those executives who responded, 4 out of 7 said they would violate the law if they could get away with it. Four-fifths agreed that they knew they were doing illegal acts in the normal course of their business. So, these are the kind of people we’re dealing with when it comes to an occupational safety and health law.

INDUSTRIAL CHEMICALS GO UNTESTEDAny new pesticide or chemical intended for use in food, or any drug, now must be tested for animal toxicity in a very detailed way—feeding it to several species of animal for two or three years, examining its carcinogenic, mutagenic (mutation causing) and teratogenic (birth defect causing) properties in great detail. No testing is required before introduction of new industrial chemicals. In general, industry wants at least a crude idea of the toxic properties of a new chemical before it is used. Often a few rats or mice (10 or 20) will be fed the chemical, exposed to its vapors, have skin and eye irritants tests done. But since there are 15,000 chemicals in industrial use today, there just isn’t much toxicity data on most of them. — Frank Mirer |

Lawyers—Bad And Good

Now the lawyers are another problem; so are our politicians. We all know about Nixon; he’s a lawyer. Mitchell’s a lawyer. So are Gray, Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Dean, Liddy, Colson, Kalmbach, Mardian, and Agnew. We could go on and on about the kind of lawyers that assist in getting these laws passed and in finding the violators.

Not all lawyers are bad. For instance, I’ve been working with a group of lawyers from the National Lawyers’ Guild. Now these guys have done some terrific work. Three years ago a man working for the Chrysler Corporation at the Detroit Axle Plant was taking hot brake linings out of his oven, putting them on the assembly line, and assembling them, all without any protective equipment. They wouldn’t give him gloves to handle the parts. The man tried to get gloves; he tried to talk to people. And although he had no prior record of any problems, finally something snapped. He went home, got his M1 carbine, loaded up, went back, and killed 2 line foremen and another worker who tried to take the gun away from him. Now his lawyers from the National Lawyers’ Guild did an unprecedented thing. They took the whole jury into that plant and showed them the kind of conditions this guy had to work in and survive under. The jury found him not guilty.

So, there are good lawyers, and I guess there are good companies, too, but in all my experience I’ve never run into one.

Aid From Medical Workers

And then, let’s talk about some of the medical people and the medical organizations. Back in 1931, in England, a Dr. Merriweather, who was a medical inspector for the British Home Office, found that twenty-five percent of the people working with asbestos in a textile plant were getting pulmonary fibrosis. That went up to eighty-one percent if they stayed in that plant for more than twenty years. Testifying before Parliament, Dr. Merriweather was asked if a young girl working in this textile plant for a period of two years would ultimately end up with asbestosis.3 Dr. Merriweather replied, “Yes, if she lives long enough.” So England, way the hell back in 1931, made asbestosis a conpensatable disease.

In this country, there are thirty-six thousand workers involved in making asbestos, and over one hundred thousand others who work with asbestos in other ways. It’s a proven fact that when anyone inhales asbestos in any form it stays in their lungs for twenty years, and at any point it can trigger cancer. Asbestos workers suffer from six times as much cancer as the general population.

The Buried Asbestos Plant

There are some good people in the medical field, such as Dr. Irving Selikoff, and quite a few others that I’ve worked with through the Medical Committee for Human Rights. Dr. Selikoff founded a medical clinic in Patterson, New Jersey. Seventeen of his early patients were referred to him from a plant making things out of asbestos for the government. These guys started working with asbestos in 1940. In 1954, the plant closed down and moved to Tyler, Texas. By 1961, six of the seventeen workers were dead, and today only six survive. Of the eleven who died, four died of lung cancer, one of mesothelioma4, three of other types of cancer, and two with asbestosis. Of the six still alive, two are totally disabled with lung disease; one has had surgery for the removal of a lung and his larynx. Johns-Manville corporation, which ended up with this plant, refused to supply Dr. Selikoff with any records. So even though there may be good medical people working on these cases, you usually have to deal with the corporations, and that’s a problem.

POLYVINYL CHLORIDE CAUSES CANCERIn February 1974, the Wall Street Journal reported that three workers in a B.F. Goodrich polyvinyl chloride plant had died of an extremely rare form of cancer, angiosarcoma of the liver. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is made by reacting vinyl chloride, a gas, with itself under pressure to form the solid plastic. A search of the scientific literature showed that in 1970 an Italian scientist had reported that inhalation of vinyl chloride gas caused cancer in rats. More cases of cancer in workers in other polyvinyl chloride plants turned up. Conferences were called by the federal government, and more information came out in the press. All the evidence isn’t in, but the story reveals a lot about the science and politics of occupational health. Vinyl chloride is by no means a rarely used chemical. It is one of the 25 most commonly used chemicals in the United States, with about 5.2 billion pounds manufactured in 1973. It’s the basis for a little less than a fifth of the plastic made in the U.S. It was; in fact, one of the better studied chemicals, and thought to be almost non-toxic. In 1970, an Italian chemical company commissioned the study in which rats were exposed to vinyl chloride everyday for a year. The material is “non-toxic” enough that rats survived a year of being exposed to 30,000 parts per million (ppm) of vinyl chloride in the air (30,000 ppm is 3% of the air). After the year of exposure, the rats were then observed for another year, and they all died of cancer. Extending the experimental results from rats to humans is both simple and difficult. The simple part is that there is no doubt that vinyl chloride exposure causes cancer in humans. However the dose/response effect is not known. In all known cases there is a “latency period” for chemically caused cancer to develop. In humans, there is always a lag of 15 to 30 years between first exposure to a chemical and the noticible onset of cancer. The gruesome fact is that the first great increase in polyvinyl chloride production and vinyl chloride exposure was about that long ago, and the exposure of the dead workers fits the pattern exactly. The Labor Department has set an emergency standard for vinyl chloride exposure of 50 ppm along with some required work practices and medical surveillance. Unions, many academics and activists in the field protested that only “zero” exposure would be safe. In effect, the Labor Department was asking workers to play “you bet your life” for the sake of an important industry, since 50 ppm was thought to be easy to achieve, while zero exposure was not (the latest report states that mice get liver cancer at 50 ppm). The story of vinyl chloride is only the latest in a series of chemical hazards discovered. Cancer is a very scary word, but it is nothing new in the workplace, such substances as asbestos, coke oven emissions, and coal tar pitch have been proven to be carcinogens. For many workers cancer-producing chemicals are a silent hazard along with the unsafe and uncomfortable conditions to which they became reconciled long ago. — Frank Mirer |

As is said before, this same company that had all the bad history in New Jersey moved to Tyler, Texas. The workers here filed complaints about the conditions, and when the government came in through OSHA, they decided things were hopeless. They closed the plant down, buried the machines, and bought back all the gunny sacks which had held asbestos but were sold to a local nursery. They literally wiped the plant off that particular area of the map.

Paul Broder, who wrote an excellent article for The New Yorker magazine, went to Tyler to interview the asbestos workers. He learned that the corporation people had spoken to one of the workers because he had shadows in the X-rays of his lungs. Well, the corporation man started asking the worker personal questions about what his private life was like. He asked, “Do you drink alot of milk?” The worker answered that he did, and the corporation guy said, “It’s probably the calcium in the milk that’s causing your lung problems. You’re drinking too much milk.” So that’s the kind of direct deliberate lies the company tell to the people in the plant.

One very significant thing happened out of this case. A $360,000 lawsuit was filed against the John’s-Manville company, and the only issue was the fact that the company was aware that this worker had asbestosis, but they didn’t tell him and they concealed the records.

The Reasons For CACOSH

Now it’s very important that the OSHA law is enforced the way it should be. In other words, nobody is going to come in to wherever you’re working and say ”We’re going to take care of your health.” It’s no more likely that someone will hand you a good contract. You have to fight for every nickle and dime from your company. Now, it’s been estimated that OSHA is going to cost the average corporation $330 per man to make its plants safe. So, you’re going to have a battle on your hands to get companies to pay out that kind of money for safety and health.

Now, it’s easy if you’ve got a broken chair or something that obviously should be fixed. But the real difficult part, and where the unions must get help, are the diseases of the body that are caused in the workplace. There isn’t any union in this country who has the facilities, the laboratory facilities and the legal staff, to do something about unhealthy working conditions.

What is possible, though, is to get together. We’ve done it in Chicago under the CACOSH (Chicago Area Committee for Occupational Safety and Health). We’ve got the United Electrical Workers, the United Auto Workers, Teamsters, Butchers, all these different unions getting together with one purpose in mind-that we can help one another. We’ve got the MCHR (Medical Committee for Human Rights), we’ve got alot of good people from the medical field, and we’ve got some lawyers from the National Lawyers Guild. You’d never find a wilder bunch of guys; it’s like a brain surgeon, a chiropractor and a dentist getting together and agreeing on a program.

Exposing A Company Doctor

One example of the services we’ve done happened in my plant, International Harvestor. There, we had a real prostitute of a medical doctor. His name is Doctor Whelter. Once he took over the sole responsibility for our company, everything suddenly changed. He didn’t want to use this OSHA Form 102, that reports lost-time accidents to the government, and that became his personal vendetta. (A lost-time accident causes the worker to miss work time as measured by the punch clock. They are reported to the government for purposes of setting insurance rates, compiling statistics, selecting targets for safety inspections, etc.)

It used to be that if you had a cast on your hand, on your arm, on your wrist, or on your foot, you couldn’t even walk in the plant. You had to have somebody else go get your check for you. Now, a guy broke his wrist, and this new doctor put the cast on. When the cast dried he sent him back to work. Now this guy doesn’t show up as a lost-time accident, even though he’s got a broken wrist, can’t work, or can’t do nothing. That’s not a joking matter, but that’s exactly what happened.

This is the kind of medical people you’ve got in some of these companies, but the only way we could combat them was through CACOSH. Because I could make my feelings known, the rest of the union people could make their feelings known—and we’ve got alot of good people who don’t like that doctor—but it doesn’t do any good because this man has got that “Doctor” in front of his name, and that makes him sacrosant.

So what we did do is to go to MCHR. There, we got Dr. Gerber from Cook County Hospital, and had her come out to our union hall. She interviewed about twelve people, and went though the history of how they were treated in the company’s medical department. Based on that, she made some recommendations. So in negotiations, we said that Dr. Whelter has got to go; that’s one of our requirements for going back to work.

Now the company knew we were serious because we had these medical facts. So at that point, the company gave us a paper, in writing, saying: “All right, go back to work, and we’ll select another doctor that’s not company or not union, have him come into the plant, evaluate what’s going on, talk to these people, and make recommendations.”

Well, unfortunately, they didn’t know that the reviewing doctor they selected to come into the plant was Quentin Young, a member of MCHR. And he did a very good job. He made some excellent recommendations, and his number one recommendation was to get rid of the company doctor.

The company is now up in arms, because they were surprised that a medical person would make such a statement to a corporation. So now they’re trying to hedge on the agreement, but we intend to strike over it.

Organization in Madison

So there are things you can do by organizations. I would recommend an organization to do these things here in Madison, if you’ve got up interest in people to get together. First of all, you’ve got to get some kind of organization; you’ve got to get some money to pay for office space; you’ve got to get people to donate equipment and money.

Once you start providing services, it’s surprising how quick people come to you because even the international unions don’t know what this OSHA law is about. They’re afraid of it. The lawyers don’t know what this new law is about; they’re afraid of it. It’s a whole new field; it’s wide open.

So your lawyers and medical people must get expertise in this field. For example, the lawyer we had was Harold Katz, who was one of our state legislators. He didn’t know what a turret lathe was. I explained to him, in court, what a turret lathe was, when we went to court with the government and our union. I also explained to him what a rachet wrench was. To him those are foreign words.

But you can’t depend on lawyers and OSHA alone, because the OSHA law has some very significant problems. For instance, it’s nice to say that you should have an organization that could do something about your exposure to dust and fumes in the plant. That’s fine to say, but you try to get an expert to go into that plant. The company won’t let them in there, just like John’s-Manville wouldn’t give Dr. Selikoff any information. If I wanted to go into your plant to look at your working conditions, they wouldn’t let me in. So the workers are the ones who are going to have to know what the conditions are, and what they should be.

This is the kind of thing where you need people to get involved. It can be done, but somebody’s got to push the issue, and it’s got to be done from the factory floor. My international union isn’t going to come out and tell me what to do. I tell them what we want.

It’s the same thing that you should do. You can’t expect the international union who doesn’t know what your safety conditions are to come out to your plant, and ask you “Is everything OK with your job?” You’ve got to tell them: I won’t work here”, or “This is wrong”, or ”This is against the law”. You’ve got to educate the international on what should be, and then if they can’t furnish you help, do like our union did: Form that other organization and get support from the international union-mine is supporting us with $150 a month.

So in one way or another, we at CACOSH are helping everybody. We’re helping the union organizations and we’re helping the lawyers and medical people to get experience working with unions.

That more or less concludes my statement.

— Carl Carlson

HOW TO LOOK AT YOUR PLANT

This article is excerpted from a pamphlet written by the Industrial Health and Safety Project of Urban Planning Aid ( UPA ), Cambridge, Mass.

YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE AN EXPERT

You don’t have to be an expert to inspect your workplace. The people who are best qualified to identify dangerous situations are the ones who have to deal with them every day — the workers on the shop floor. With a few ‘basics, outlined in this pamphlet, anyone can learn to spot the dangers and take action to get them eliminated.

FINDING THE HAZARDS

The first step in a plant survey is to list in your notebook the problems you already know. Get as many people as possible to add the hazards-they know of to the list.

Questions like these can be answered simply and quickly:

Is noise so loud that it makes your ears ring or leaves your hearing dulled after work?

Do any vapors or fumes give you headaches or make you dizzy?

Do any oils or solvents give you skin rashes?

Do metal fumes ever make you feel like you have the flu?

Does dust make you cough and sneeze?

Are cranes lifting loads heavier than they’re rated for?

Is any machinery or equipment faulty?

Some accidents are caused by obvious hazards — unguarded machines or inadequate lighting or slippery floors, for instance. Check every accident to find the cause. It could be a hidden hazard like the ones listed below.

Lack of Information. People sometimes act carelessly (and cause accidents) because management never informed them of the dangers involved in working with certain substances and processes.

Slowed Reactions. Some chemicals reduce the ability to concentrate, or slow reaction time. Used without proper ventilation and protection, these chemicals threaten workers with a higher chance of accidents.

Noise. Accidents can happen because shouted warning are drowned out.

Speedup. Working too fast can make it impossible to respond to unexpected situations. Minor accidents could become serious.

Pressure management to deal with hazards that cause accidents right away, when feeling is running high and management can’t offer easy excuses.

HEALTH HAZARDS

Workplace dangers to health are often more serious than accident hazards. Something that causes mild symptoms now could have serious long term effects, and is bad for you now. Don’t ignore headaches, frequent coughs and colds, dizziness, or skin irritations. They could easily be due to conditions at work.

Management will probably not admit any connection between an illness and the job. They prefer to blame bad personal hygiene, or allergies, or smoking — anything which gets them off the hook. But you don’t have to put up with unnecessary sickness caused by your work.

Find out whether a number of workers around the shop or plant suffer the same symptoms. If they do, their health problem is probably work-related.

MAKE A FULL LIST

Make a section in your notebook for dusts, mists, fumes, vapors, and smoke. They are annoying, and can be dangerous. Mark down the locations, the characteristics, and the source.

Unfortunately, you can’t really measure the hazard levels in the air without using certain instruments. Some of them are easy to operate and can be purchased by your local. They can also be borrowed from UPA.

You could call in the state to make tests, but you are better off first doing your own.

In your survey, however, you don’t have to wait for the instruments. You can make the following preparations.

Wherever you find dust, mist, fumes, vapor or smoke, check the operation producing them. Find out what substances are being used.

Is there ventilation? Is it faulty? blocked? inadequate? If there is anything wrong with the ventilation, you could make strong demands for repairs.

It’s a good idea to list in your notebook all substances used in your plant—chemicals, oils, solvents, etc.

Put the brand name labels in if you can. If you can’t, copy them. Get all the details you can from labels.

All of these things are potential hazards. An otherwise good oil for instance, can cause skin irritations if not changed often enough.

Later on you can research many of these substances, especially the suspicious ones. This information could be used in an education campaign, and to prepare for inspections.

USING YOUR NOSE AS A TESTER

You can’t usually rely on your nose to tell you when you are getting too much of a substance. The concentration you can smell is usually much higher or lower than the legal limit for exposure.

But there are a few chemicals you can test very approximately with your nose. If you can smell one of these substances:

Chlorine

Ammonia

Methyl Alcohol

Trichloroethylene

Tetrachloroethylene

then you know you are getting too much of it.

But, especially with the solvents, too much of a substance may dull your sense of smell, so if you can’t smell it, but it seems to give you headaches, or make you feel bad in other ways, you may still be getting too much.

A NOTE ON LEGAL LIMITS

Mark down in your notebook any areas where there are extremes of heat and cold, or excessive noise. These hazards can be more dangerous than people realize. You will certainly want to have tests performed in these areas.

Look for monitoring devices. Write down the locations, the warning levels, and the hazard being watched.

Monitoring devices are instruments that measure how much of a hazard is in the environment, and are set to give a warning or indicate when a set level is exceeded.

To find out what the monitor is for, check the label, and ask the company. If necessary, grieve.

Be sure the levels conform to the legal requirements. These instruments are sometimes altered — for the management’s convenience. Be sure they are set properly, and really work.

You might think about making the installation of monitors one of your health and safety demands. Perhaps they would be useful in areas subject to air hazards, heat, and noise.

If you work with any materials that give off radiation, the shop should have appropriate monitoring devices.

ELIMINATING THE HAZARDS

Getting the hazards eliminated isn’t going to be easy. Management will resist spending money to improve shop conditions—profits always come first. To succeed in your health and safety drive you will need strong shop floor support.

You will also need organization—perhaps the people you involved in the shop survey could form into a rank and file health and safety task force. This could become the basis for an on-going health and safety committee.

Make your demands specific: Look for some success, no matter how small, at the beginning. Success builds support.

During the shop survey you had a chance to hear suggestions from fellow workers on how to eliminate hazards. Follow through on them.

Be sure to use the poll you conducted to find out what hazards people are most conscious of, and want eliminated first.

FORM A UNION COMMITTEE

You or the committee can help debunk management’s claims that they will go broke if they have to fix up hazards. Ask for estimates of the cost of solving each problem. Ask where they got their estimates- the precise engineering firm, the manufacturer of safety devices and improvements, the consulting firms. If you can, check out these figures. (You may find management never bothered to talk with them in the first place.)

Having to give you concrete estimates will make it harder for the company to talk in vague terms about layoffs or moveouts caused by fixing up the hazards you find. Obviously, it’s even better if you can get your own cost estimates, or costs for your own solutions which are cheaper than theirs.

If you decide to file a grievance about a hazard, prepare it carefully. The more facts you have, the better your chances for success.

The grievance procedure can be slow and difficult. It can be useful in some situations, but it doesn’t pay to rely on it. Filing a grievance can get a problem fixed—as long as it’s easy for management to correct, and not too expensive.

You can also grieve for information about a process or material used in the plant. But don’t rely on any information gotten from management. It will probably be technically correct, but could easily be misleading. Do some research of your own.

CONTRACT CLAUSES

Getting a good health and safety clause written into the contract can establish the union’s right to a say in work conditions. This is crucial. More control by workers over their workplace environments can bring better conditions.

The Right To Walk Off: Workers should be clearly allowed to stop work on a particular job if they consider conditions immediately dangerous. Federal law provides for this action, but the protection it provides is limited and hard to use. Writing this clause into the contract will offer more realistic protection.

Hazard Deadlines: The contract could require the company to correct specific hazards by a set date.

Standards: Writing legal standards into the contract gives you the advantage of negotiating through the grievance procedure whenever standards are neglected or ignored.

Information: The company should have to supply workers with full information about every substance or process used in the plant.

New Processes and Substances: The union should have the right to check out all processes and substances before they are introduced to the plant.

USE THE LAW

Under federal law, workers have the right to accompany the inspector and point out problems. Take advantage of this. Use all the information you found through your plant survey and your research. Be sure the worker selected to accompany the inspector is really informed, and not afraid of management.

To call for an inspection, you simply fill out a written request form available from the nearest OSHA (Occupational Health and Safety Administration) office. You must sign your name, but you can bind OSHA not to reveal your name to the company by checking off a box on the form.

In cases of imminent danger, you can put in a phone call (preserving your anonymity, if you wish). An inspector should come as soon as possible.

If you do call for an inspection, be alert. Don’t rely on management to tell you that an inspection is about to begin.

Whenever the inspector arrives, he, or she should ask for a union or workers’ representative who is supposed to accompany him. Be sure that people are ready. Alert all parts of the plant about an expected inspection. Let people know to check that the inspector is accompanied.

Workers also have the right to see the inspector’s report. If there are any violations, the government can fine the company on the spot (But don’t bet on it — it’s almost never done.) The inspection results and any fines imposed must be posted publicly in the workplace. They cannot be taken down until the violations are corrected.

Again, take the initiative. Get a copy of the inspector’s report and any fines imposed. Make sure that the results, fines, and hazards cited are posted and that other workers get to read them.

Even if the inspection goes well, and you have a chance to voice your complaints and point out hazards and management neglect, don’t rely on the government to take care of the problem. The company can appeal fines and penalties and usually wins long extensions in the time allowed to correct hazards. Fines are almost always chopped down to a token amount on grounds of “good faith” or a good safety record.

So it’s still up to you. Health and safety problems must be dealt with at the point of production. Think of how you can use the inspection, but don’t mistake it for a solution. It can dramatize the problems, and be used to emphasize the need for shop solidarity, rank and file initiative, and union militancy.

UPA provides free assistance to unions in trying to understand and correct health and safety problems.

For this and other pamphlets or assistance, call or write:

Industrial Health and Safety Project

Urban Planning Aid

639 Massachusetts Ave.

Cambridge, Mass. 02139

(617)661-9220

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 4 <<

NOTES

- Emma Goldman (1869-1940) immigrated to the U.S. from Russia as a young woman shortly before the Haymarket murders in Chicago in 1887. She became a nurse and militant anachist. Imprisoned many times for her advocacy of free speech, free love, birth control and draft resistance; during World War I she was eventually deported to Russia.

- The forty cent edition is still available in limited quantities from Science for the People.

- Asbestosis is scarring of the lungs caused by asbestos.

- Mesothelioma is a cancer on the walls of the lung cavity.