This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Cable TV

by Ross Feldberg

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 1, January 1974, p. 44 – 45

The appearance of a new technology such as cable TV invariably serves to distinguish between those who regard technology as a neutral tool and those who view technology as a part of the overall political system, subject to the constraints of that system. Amitai Etzioni, along with a number of academics, lies outside of even those two categories. Viewing society as a basically harmonious social order in which conflicts reflect misunderstanding rather than basic and real differences, Etzioni imagines cable TV as a technological “shortcut” to participatory democracy. Nowhere in his description of the possibilities of cable TV does Etzioni consider that participatory democracy may not be in the interests of those who presently wield power. Other commentators have also envisioned cable TV as the source of a “communications revolution”. The U.S. is to become the “Wired Nation” (as if we weren’t already) with cable TV providing, in addition to its normal’ television function, audio, video and facsimile transmissions that will allow us to obtain newspapers, do our banking, receive library information, communicate with medical personnel and even shop—right in our homes or apartments. Community organizations have advocated cable TV on the basis that it could serve as “community television” with programs by and for the local community. None of these hopes for the development of cable TV take into account who is developing this technology and for what purposes.

The appearance of a new technology such as cable TV invariably serves to distinguish between those who regard technology as a neutral tool and those who view technology as a part of the overall political system, subject to the constraints of that system. Amitai Etzioni, along with a number of academics, lies outside of even those two categories. Viewing society as a basically harmonious social order in which conflicts reflect misunderstanding rather than basic and real differences, Etzioni imagines cable TV as a technological “shortcut” to participatory democracy. Nowhere in his description of the possibilities of cable TV does Etzioni consider that participatory democracy may not be in the interests of those who presently wield power. Other commentators have also envisioned cable TV as the source of a “communications revolution”. The U.S. is to become the “Wired Nation” (as if we weren’t already) with cable TV providing, in addition to its normal’ television function, audio, video and facsimile transmissions that will allow us to obtain newspapers, do our banking, receive library information, communicate with medical personnel and even shop—right in our homes or apartments. Community organizations have advocated cable TV on the basis that it could serve as “community television” with programs by and for the local community. None of these hopes for the development of cable TV take into account who is developing this technology and for what purposes.

“If citizens sense that their needs are ignored, the new technological system may make them more aware of this condition … If their expectations are unrealistic, it might help them adjust their aspirations.”

— Amitai Etzioni, in Policy Sciences

Cable TV began with small businessmen in rural areas putting up sensitive antennas on high towers and transmitting the received television signals to local sets via cable. Through the 1950’s and into the early 60’s, the cable TV industry remained small, fragmented and mainly uncontrolled by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). As the potential for this new technology became apparent, increased pressure from the established broadcast industry succeeded in forcing the FCC to freeze cable TV expansion in 1966. This freeze lasted until December, 1968 when the FCC issued its “Proposed New Rules and Notice of Inquiry”, and during this two-year period of uncertainty ownership patterns for cable TV systems showed a marked change. By 1969, 75% of cable TV system ownership resided in the hands of TV-radio broadcasters, telephone companies and newspapers. Big business was investing in cable TV franchises for big profits. Due to the high level of initial investment, exclusive franchises are invariably demanded so that cable TV functions within each area as a monopoly. Expectations that cable TV will provide a real alternative to the pablum we currently receive from the established media are likely to prove overly-optimistic, since the industry is hardly as excited about increasing the possibilities for participatory democracy as it is in the creation of a vast new market in communications and merchandising. Given the costs for installing the cable, it is not likely that the cable TV industry will turn to the ghettos of the inner city for their subscribers. Demands for public access channels are being met with resistance by the industry and are being only minimally fulfilled. All of this is to be expected, since technology in a capitalist system inevitably reinforces and enlarges the already existing social and economic inequalities. Technology for profit means technology for those who can afford to buy it.

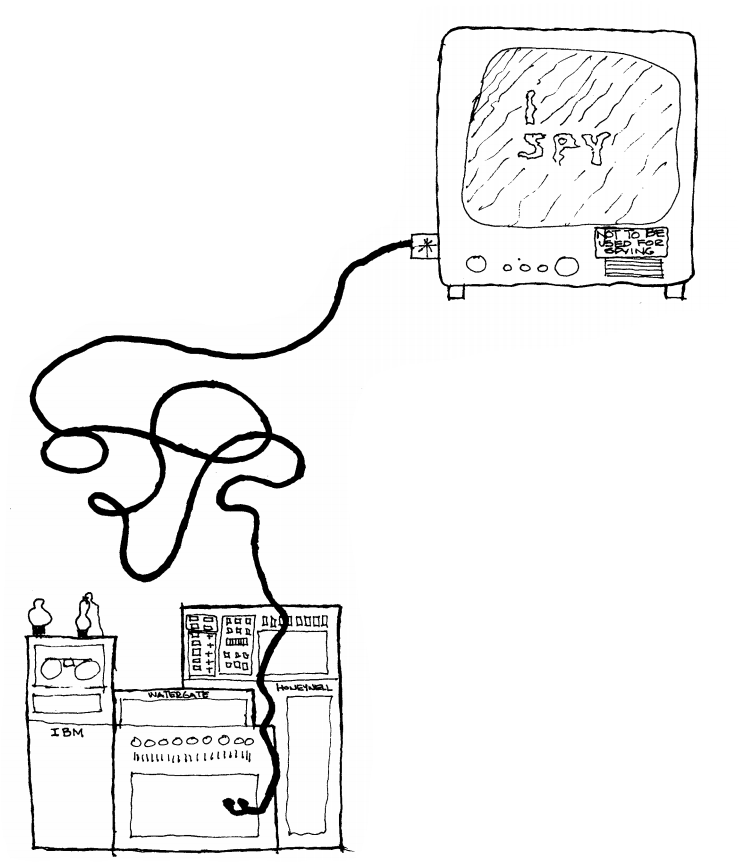

What will be the future for cable TV? Although its potential for functioning as the “electronic town hall” is small, its potential for the creation of a vast new market in communications is great. Along with the development of this market, it is inevitable that governmental monitoring of our lives will increase. For those who choose to bank, shop, or conduct medical interviews over cable TV there is the real· possibility of computer compiled files of their everyday transactions. Tapping cable TV will be just as easy as tapping telephones. (When a participant in a session at the American Association for the Advancement of Science meetings in Washington, D.C. in 1972 protested to Etzioni that she didn’t want a cable TV installation since she already had a “two-way cable communications system” in her house—the telephone—and she suspected that it was already tapped, Etzioni’s reply was that if she was worried about spying she could always unplug her cable TV!). A less obvious threat is that cable TV could provide the government with a much more sophisticated propaganda tool. In the ultimate in “community television”, the government could direct messages to different ethnic, racial, and class groupings, which could differ slightly in their contents. (Want to explain why the presidential tapes are missing? Try three alternate explanations to selected areas of one city, do an automatic electronic poll to determine which has been received most favorably, and then use that one for the rest of the country.) Automatic polling, determining which program each set is tuned in to at any specific time, also has a great potential for a new form of preventive surveillance. The scenario might read like this: the government, in a study of 1000 known community organizers has developed a profile of their viewing habits over an extended period of time. Computers then scan the output from tens of thousands of cable TV sets over a period of time. Individuals whose viewing profiles are congruent or largely overlapping with those of the activists are then selected out for “further study”. In this way, “troublemakers” could be identivied even before they ever began to make trouble.

“The idea that technological developments might be used to reduce the costs and pains entailed in dealing with social problems is appealing.”

— Amitai Etzioni, in Science

Within the confines of our society, the technology of cable TV represents a “progress” filled with contradictions and dangers. Liberal analysts, such as Jerrold Oppenheim or the American Civil Liberties Union, have advocated a set of legal safeguards to protect individual privacy. However, given the readiness of the government and its various police forces to disregard the legal rights of individuals, it is unlikely that such barriers will give more than the illusion of protection. Nor can we expect the FCC or the Office of Telecommunication Policy to protect the public interest in regulating this new industry. What, then, can be done? At this time, we feel that it is necessary to oppose the introduction of cable TV to new areas and to limit its development until our society is structured to allow the people to take advantage of its technology. Where cable TV systems have already been installed, it is important that community organizations be supported in their struggle to obtain the most open and community-directed cable TV possible. Finally, we must be willing to confront those technological apologists who, rather than deal with the nature of an unjust society, would try to buy us off with irrelevant “shortcuts”.

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 1 <<