This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Chile: A History of Imperialism and Struggle

by Jeanne Olivier, Manuel Valenzuela, Ginny Pierce, & David Barkin

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 6, November 1973, p. 8 – 23 & 33 – 37

A CHRONOLOGY: 1847 – 1970

In compiling the chronology, we tried to include those facts which could summarize the development of political awareness of the working class and its participation in the Chilean leftist political organizations which made the electoral victory possible. This way of describing a historical process cannot explain the internal struggles from which the facts emerge. The politicization of the working class is seen in terms of strikes and elections, rather than the daily struggles which gave rise to those strikes and the growth of working class political parties. Allende’s government has been dismantled but the power of a politically deep-rooted working class cannot be dissolved. The coup can be seen as another Iquique Massacre—a starting point for defining better tactics which will lead to final victory.

Much of this chronology was taken from New Chile, 1973 Edition, published by the North American Congress on Latin America. This book is an excellent source of information on the first three years of Allende’s presidency. It can be obtained from NACLA. Box 226, Berkeley, California or Box 57, Cathedral Station, New York, New York. Other sources used were: The Chilean Revolution, Conversations with Allende, by Regis Debray; Latin America, Reform or Revolution, by James Petras and Maunice Zeitlin; Latin American Radicalism, edited by Irving Louis Horowitz, Josue de Castro and John Gerassi; and “Chile: Struggle for Socialism” from the Guardian, special supplement, June 1972.

1847 Establishment of the Sociedad de artesanos, the first workers’ association on the continent. Lacking class consciousness, this was primarily a fraternal organization.

1890 The country’s first general strike spread from Iquique, a northern mining area, throughout the country.

1903 First strike of port workers in Valparaiso.

1906 Luis Emilio Recabarren, a linotype operator and the first working class Socialist leader, was elected as Deputy from the mining area, Antofagasta.

1907 Iquique Massacre. Ten thousand nitrate miners marched through Iquique demanding higher wages, higher safety standards at work, and an end to the exploitation of company stores. Machine gunned by the militia, 2,000 men, women, and children were killed. At this time the nitrate mines were owned largely by the British.

The first social legislation actually put into practice was the “Law of Sunday Rest”.

1908 The Chilean Workers Federation (FOCH) was founded as a mutual aid society by conservatives.

1911-1920 This period witnessed 293 strikes involving 150,000 workers.

1912 Initiating the Left’s long electoral struggle toward socialism, Recabarren founded the first working class political party, the Socialist Workers Party.

1919 FOCH, which had become a militant industrial trade union, called for the abolition of capitalism and became affiliated with the Communist International Trade Union Movement which had been organized in Moscow. By this time FOCH was the major workers’ organization with 136,000 members, 37% of whom were miners.

The miners took the leadership in an early attempt at rural organization. In 1919 an abortive effort was made to mobilize the inquilinos (tenant farm workers) into a nationwide federation in the Cometa region in the Aconcagua Valley.

1920 The Liberal Alliance’s presidential candidate, Arturo Alessandri (whose son opposed Allende in 1970) was elected president. Supported by the middle class and by some sectors of the working class, Alessandri was the first president to try to win political power by mobilizing the masses on the basis of a socio-economic program. The middle-class hegemony which followed this election produced many changes in Chilean life; nevertheless, conditions for the masses remained difficult, and throughout the twenties the parties of the Left began to grow.

1921 The Chilean Socialist Workers Party, founded by Recabarren in 1912, became the Communist Party of Chile (PC) and joined the Third International. Though Communist Parties had been organized in other parts of Latin America, only in Chile was the PC a workers’ party in origin as well as in ideology.

1925 After three years of discussion, the Senate adopted a Labor Code remarkable for its time, as well as a series of laws on the eight hour day, labor contracts, occupational accidents and trade union law.

Coruna massacre. Three thousand workers were killed in the saltpetre mines.

The Communist Party was outlawed under the presidency of Arturo Alessandri.

1927 In his first bid for the presidency, Carlos Ibanez obtained 98% of the votes and inaugurated the government known as the “Ibanez dictatorship”.

1930’s A broad militant movement of peasant unionization developed, supported by sectors of the urban working class; the movement was violently repressed by the state and politically defused by the electoral strategy that the leftist parties adopted during the Popular Front.

June 4–16, 1932 The Socialist Republic of Marmaduke Grove. A socialist government was established by a revolutionary movement headed by Colonel Marmaduke Grove (military leader) and Eugenio Matte (civil leader). Under the slogan “Bread, a Roof and Shelter”, the new anti-imperialist government embarked on a series of measures in the interests of the dispossessed. The program of the revolutionaries did not, however, attempt either the socialization of the means of production or the confiscation of large fortunes. Moreover, the government did not depend decisively on the workers to mobilize its program. After twelve days the “republic” was overthrown by a coup d’etat.

December, 1932 Arturo Alessandri was elected president with 163,744 votes over Marmaduke Grove’s 60,621. Alessandri had grown more conservative and presided over a repressive government which banished and imprisoned leftist leaders. The repression which eventually alienated even the Radicals furthered the creation of a united leftist opposition. (The Radical Party has traditionally represented the center in Chilean politics, expressing the hopes of a growing middle class.)

April 19, 1933 Founding of the Socialist Party of Chile. Like the PC the Socialist Party was Marxist and drew its support from the workers. Allende, one of its founders, explained:

… we believed that there was a place for a Party which, while holding similar views in terms of philosophy and doctrine [as the PC]—a Marxist approach to the interpretation of history—would be a Party free of ties of an international nature. However, this did not mean that we would disavow proletarian internationalism.

1935–1936 A growing fascist threat favored the development of an alliance between the workers and the bourgeois democratic forces. In March, 1936 a Popular Front was formed by the Radical, Communist, Socialist, and several smaller parties as well as the Chilean Labor Federation. The Front was dominated by the Radical Party and pushed for the defense of democratic liberties and some economic reforms.

Sept., 1938 An attempted coup by Chile’s small Nazi Party resulted in severe repression and the imprisonment of presidential candidate Ibanez who had been implicated in the coup. In retaliation Ibanez instructed his followers to support the Popular Front candidate over Alessandri’s chosen successor, Gustave Ross.

December, 1938 As the presidential candidate for the Popular Front, Pedro Aguirre Cerda, a member of the Radical Party, won a 4,000 vote victory. Reformist in nature, the Cerda government inaugurated some social legislation, but the upper and middle classes ultimately benefitted more than the workers. The administration’s real importance lay in the opportunity it gave the Socialists and Communists to pursue their organizing activities. During 1939 and 1940 the number of unions and unionized workers grew rapidly, and farm workers’ unions appeared for the first time.

1942 A Radical, Juan Antonio Rios was elected president with the support of the Communist and Socialist Parties. Moderate reforms were accomplished, but the income of the working class increased only 1% per year.

January, 1943 Shortly after the U.S. entered WWII, Chile broke relations with Japan and Germany and was rewarded by the U.S. in the form of Lend-Lease arrangements and Export-Import Bank Loans.

1946 Due to the death of President Rios, new elections were held and Gabriel Gonzalez Videla was elected with Communist support. He assigned three Communists to his eleven-man cabinet.

April, 1947 In the municipal elections, the Communists received 71% of the coal miners’ vote, 63% of the nitrate workers’ vote, and 55% of the vote of the copper workers. Nationally, in contrast, they received only 18% of the vote. The Communists drew their support largely from unionized labor rather than the peasantry. Until 1937 farm worker unions were illegal and severely repressed. In fact, as late as 1965 there were officially only 20 farm workers’ unions, with 2,000 members nationwide.

1948 President Videla, under pressure from imperialism and the national bourgeoisie, dismissed his three Communist ministers. The vacancies were filled by three Socialist Party leaders. He broke with the Communist Party on the alleged grounds of international conspiracy and promulgated the Law in Defense of Democracy, starting the bloody repression of Communist militants. The Law in Defense of Democracy was conceived as a means to outlaw the Communist Party, which remained illegal for the next ten years. The party’s 40,000-50,000 members were struck from the voting registers and many leaders were deported or jailed. The Communist Party continued organizational activities underground, supporting the Socialist Party and Allende’s presidential candidacy in 1952.

1949 Women are enfranchised. Before this time only 10% of the Chilean population voted. By 1957, 19% vote and by 1961, 25%. A literacy clause kept illiterates disenfranchised until after Allende. was elected in 1970.

1951–1952 Deteriorating economic conditions led to skyrocketing prices, frequent strikes and demonstrations.

1952 Allende was nominated as presidential candidate for the first time. He was supported by the Frente del Pueblo, or People’s Front (FRAP), a coalition of the underground Communist Party and a faction of the Socialist Party. Carlos Ibanez, nominated by a conglomeration of independent forces, won 50% of the votes, defeating the three other candidates. Allende received only 5.4% of the vote.

February, 1953 The militant leftist Central Workers’ Organization (Central Unica de Trabajadores, or CUT) was organized after a long period of division within the leftist workers’ ranks. The CUT was a strong supporter of Allende in 1970.

Sept., 1955 The Klein-Saks advisory mission, led by Prescott Carter of the National City Bank and organized by the Washington consulting firm, Klein Saks, released its blueprint for Chilean development. Contracted by President Ibanez, on the urging of Agustin Edwards, one of Chile’s most influential oligarchs, the mission recommended reducing social programs, reducing government intervention in the economy, and opening the economy to more foreign investors.

1955 The U.S. Cerro Copper Corporation, with large operations in neighboring Peru, purchased the Rio Blanco Copper Mine.

1956 The Popular Action Front (FRAP), a coalition of the Socialist and Communist Parties, and several smaller parties, was formed. FRAP supported a common slate of candidates at election time and presented a fairly united front against Ibanez’ government. Unlike the Popular Front of the 1930’s and the Unidad Popular of 1970, FRAP did not include the centrist Radical Party.

1957 Two students were killed in student demonstrations to protest a decision to raise bus fares. This led to large scale riots which included thousands of the urban poor. The army was called in and between 40 and 60 people were killed.

1958 The Defense of Democracy law was repealed and the Communist Party became legal again. The party took an active role in FRAP and supported Allende’s presidential campaign. The conservative Jorge Alessandri, son of the past president, was elected. Allende, representing FRAP, lost to Alessandri by only 35,000 votes out of the 1.3 million cast.

Both the Popular Action Front (FRAP) and the Christian Democrats had been organizing peasant unions and advocated programs of agrarian reform. The 1958 elections showed that the Popular Front was penetrating and broadening its support among the farm workers, in part through the diffusion of political awareness from adjacent mining areas.

March 1961 Congressional Elections. The Chileans expressed their discontent with Alessandri’s government; FRAP registered a greater increase in voting strength than any other political organization.

1962 Electoral code was revised; voting became legally mandatory for all literate adults. However, 1/5 of the population and 1/3 of the working class were still prohibited from voting by the literacy clause.

Nov. 1962 The first Agrarian Reform Bill was passed. CORA, the agrarian reform agency, was established.

1964 Eduardo Frei, for the Christian Democrats, defeated Salvador Allende, again candidate for FRAP. Frei’s campaign was designed to scare the electorate away from Allende. With up to $1 million per month from U.S. sources1, Frei promised a “Revolution in Liberty” and headed a massive propaganda offensive saying that FRAP meant Communism and Communism meant the end of all freedom. Largely because of these scare tactics, Allende lost the election by a wide margin.

Regis Debray said of the Christian Democratic government (1964-70),

Delegated to its post by the bourgeoisie, Christian Democracy in power for six years built up the conditions for a revolutionary process, against its will, of course: it cleared the ground by its verbal populism for real popular conquests; it underlined and legitimized the need to take radical measures by its clumsy velleities; it raised the threshold of ideological tolerance in the middle strata … Christian Democracy was the first victim of its own instrument of ideological rule. In fact, inside its reformist project—the integration of the unorganized subordinate classes into the reigning system of exploitation in order to modernize its mechanisms and ensure a higher profitability — there developed at the base a spontaneous mass movement of a revolutionary kind, which inevitably overflowed the bounds set by the project itself2.

March 1965 Congressional Elections. Christian Democrats won all 12 contested Senate seats and gained a majority in the Chamber of Deputies. FRAP received 22% of the vote.

1965 Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR) was founded at University of Concepcion. Organized from student and leftist groups dissatisfied with the political strategy .and tactics of the traditional left parties, they criticized the Chilean Communist Party for being too bourgeois to lead a revolution and for following the Soviet line uncritically. Though many Miristas were former Socialists, they criticized the Socialist Party for its insistence on the electoral path to revolution. MIR believes that peaceful revolution is impossible, that armed struggle is inevitable. They have written “The seizing of power by the workers will be possible only through armed struggle. The ruling class will not surrender its power Without a struggle…”3 By 1970, MIR will be a significant force in the Chilean Left, with especially strong support among the homeless squatters in Santiago and the campesinos in the country.

March 1966 Workers in the U.S.-owned El Teniente mine went on strike for higher wages. A sympathy strike among other northern miners was declared illegal by the government. Troops invaded the union building at Anaconda’s El Salvador mine; six mine workers and two women were killed, forty were wounded.

April 1966 Chilean legislature passed “Chileanization of Copper” law providing for partial nationalization of American-owned copper mines.

March 1967 Municipal Elections. Left’s support among the electorate rose from 22% in 1965 to 30%. The Christian Democrats won 35.6% of the vote,-seven percent less than in the parliamentary elections in 1965.

Nov. 1967 Nationwide strike was called to protest government proposal to cut workers’ salaries and temporarily prohibit the right to strike in order to control inflation. U.S. trained and supplied soldiers and the Grupo Movil (specially trained anti-riot police) crushed the strike with helicopters, tear gas, crowd-control tanks and guns. In Santiago, seven were killed, including 4 children, and many wounded.

1968 In a special election in the south to fill a vacant Senate seat, the Radical Alberto Baltra was elected with the support of Radicals, Socialists, and Communists, foreshadowing the Unidad Popular.

March 1969 The Massacre of Puerto Montt. The Grupo Movil killed 9 and injured 30 farmworkers in the southern city of Puerto Montt as they forcibly evicted I 00 peasant families who had peacefully occupied· a piece of unused land.

In the parliamentary elections the Christian Democrats lost their absolute majority. They received 29.8% of the vote. The Communists and Socialists together received 28.1%.

May 1969 Outraged by Puerto Montt Massacre, left wing members of the Christian Democrat party defected and formed MAPU, the Movement of Popular Action, later an important part of the Unidad Popular. Jacques Chonchol, who had been responsible for Frei’s agrarian reform program, was named secretary general of MAPU.

June 1969 After students at University of Concepcion battled with police and leading Miristas were arrested and tortured, MIR sent many of its militants underground. Student cadre, who were still the bulk of the organization, were sent into the countryside and the poblaciones (poor towns or camps). In the next two and one half years, MIR’s actions included expropriations from banks and supermarkets, bombings of imperialist targets like The First National Bank of New York, armed seizures of land for squatters camps, consciousness-raising and fund-raising. During this time MIR changed from a movement of students and intellectuals to the beginning of a mass-based, disciplined party.

Oct. 1969 The Tacnazo. Two units of army division revolted in suburban Santiago (Tacna). The first military uprising in Chile in 37 years, the revolt was led by General Roberto Viaux, who said that his sole purpose was to gain a hearing with the president to express the grievances of army officers, such as low pay and lack of adequate equipment. Frei’s government saw the revolt as the first stage of a coup d’etat and quickly suppressed it. Viaux will be in the news again in 1970 when he is implicated in the assassination of General Rene Schneider.

Oct. 1969 Coordinating Committee of the Unidad Popular was formed, culminating months of discussions and plans to form a United Front.

Dec. 1969 The Programma Basico de Gobierno, (Basic Program of Government), the Unidad Popular’s plans for Chile, was approved by the member parties.

Jan. 1970 The Coordinating Committee of the Unidad Popular nominated Allende as UP presidential candidate. Other candidates for the UP nomination were Pablo Neruda, from the Communist Party; Alberto Baltra, from the Radical Party; Jacques Chonchol, from MAPU; and Rafael Tarud, from API.

Sept. 1970 Presidential Elections Salvador Allende won the election and Chile became the first country in the world to elect a Marxist socialist president. The results of the election were: Allende (UP), 36.2%; Tomic (Christian Democrat), 27.8%; Jorge Allesandri (Independent), 34.9%. Since Allende did not receive a majority, a special vote of the legislature was necessary to confirm him as president.

MIR’s position during the election was that voting would be only “a partial and formal expression” of the general social mobilization and-would have importance only within that context. Its strategy was to leave the electoral struggle to the “traditional left”, holding that both this struggle and their own program were not contradictory. MIR cadre in the mass organizations urged critical support for Allende’s candidacy.

Oct. 1970 Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Rene Schneider, a military leader committed to non-intervention in the political process, was shot and killed by right-wing terrorists who hoped to kidnap him and provoke a military coup the eve of the special congressional election necessary to confirm Allende as president.

Oct. 24, 1970 Congress overwhelmingly proclaimed Allende as Chile’s president.

Nov. 3, 1970 Allende was inaugurated.

— Jeanne Olivier, Manuel Valenzuela, & Ginny Pearce

PRELUDE TO A COUP: AN ANALYSIS FROM CHILE

Accompanying the following article was the letter below, dated July 18, 1973, and signed Fuente de Informacion Norteamericana Santiago, Chile.

Chile is entering a decisive stage in its history. Tensions and conflicts which have been held in check for many years are finally surfacing. This process is complex and extremely serious and, as such, warrants the understanding of the U.S. people.

As U.S. citizens who have been living in Chile since 1970-1971, and who, like everyone else, have been caught up in this increasingly conflictive process, we feel that the people in the U.S. probably do not fully understand the importance of recent events. Unfortunately, one of the reasons for this lack of comprehension is the way in which the U.S. press and its wire service have covered events in Chile during the past few years; the way in which they have consistently distorted and misrepresented the roots of the present conflict, the real forces involved, and the true significance of recent events.

In this brief and hurriedly prepared document, we can neither present a complete summary of recent events in Chile nor untangle all the misrepresentations and half-truths which appear in U.S. news reports. All we can hope to do is expose some of these systematic distortions and give you a general framework through which you can begin to understand the real significance of events here.

Introduction

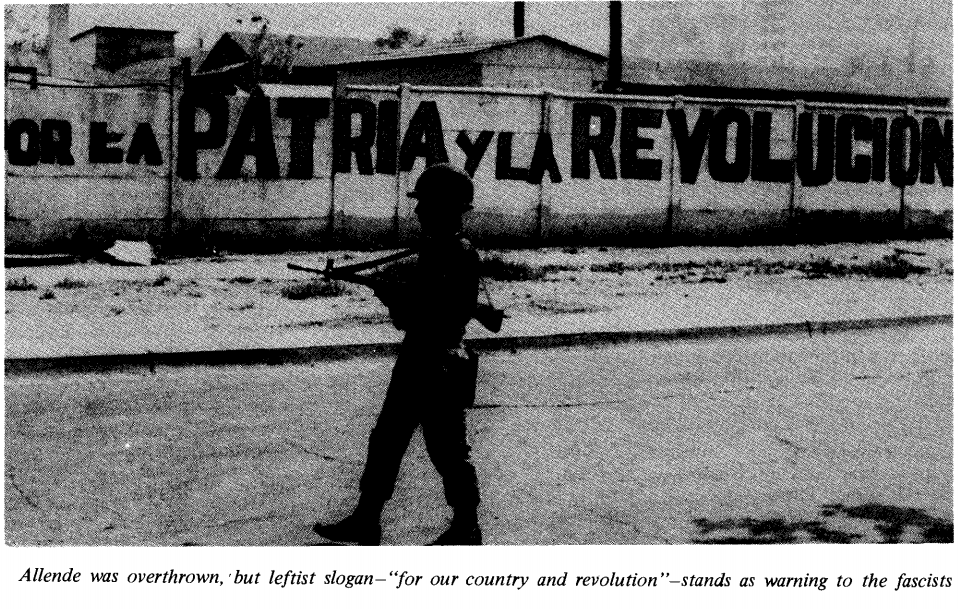

The recent attempt by sectors of the Chilean army and the fascist organization “Fatherland and Liberty” to topple the Popular Unity (UP) government by means of a military coup made it apparent to both Chileans and foreigners alike that this nation’s “peaceful road to socialism” is fast exhausting itself. The June 29th uprising, though quickly crushed by loyal troops, has ushered in a new stage in Chile’s stormy process.

In the weeks following the attempted coup hostilities have mounted dangerously. The opposition parties, the Christian Democrat (PDC) and the National Party (PN) (the latter closely linked to “Fatherland and Liberty”) have issued threats and ultimata to the government. The gist of these is that either the UP renounce its basic program of transition to socialism or “accept the responsibility for any violence which might occur”. In the past, the UP’s enemies have not balked at restricted and strategically timed use of violence. This violence has included the murder of Army Chief, General René Schneider just before Allende took office, shooting peasants in the South, burning UP party headquarters, bombing a government TV broadcast tower, and many other incidents. But now, for the first time, significant segments of the opposition advocate nothing short of a military takeover by the nation’s “constitutionalist” armed forces.

Confronted by this blatant rejection of the legal structures within which the UP set out to move towards socialism, workers throughout the country have occupied their places of work and have vowed to defend them “to the end”. In short, dialogue has all but ceased, the nation’s institution framework is tottering, and there now seems little to save Chile from open and widespread conflict.

What has brought Chile to this point? A view prevalent in the U. S. press is that the economic chaos and political instability created by the UP have broken down existing structures to a point that only drastic action by “democratic” forces can restore the peace and well-being which supposedly characterized pre-UP Chile.

The main problem with this view is what it leaves unsaid about Chile’s past.

Economic disorder, extreme social and political in stability have indeed made Chile a difficult place for anyone to live at this point. But the current turmoil is hardly an example of life under socialism. Rather, it should be clearly understood to be the chaotic and explosive state of affairs caused by the all-out efforts of a powerful minority to preserve the inherently chaotic and violent system through which it has long prospered.

Under that system Chile, a nation blessed with vast reserves of natural wealth, has been unable to provide the majority of its people with the basic necessities of life. When the UP took office, 40% of Chileans suffered from malnutrition. Shortly before this, 68% of the nation’s workers were earning less than what was officially defined as a subsistence wage; another large number of people were living slightly above what we would call the poverty level. And while allowing millions of Chileans to live under such conditions, this system permitted foreigners to drain off vast quantities of the nation’s natural wealth. In the past 60 years alone, the U. S. copper companies operating in Chile have taken home profits equivalent to half the value of ail the nation’s assets, accumulated over a period of 400 years. What little remains of the country’s wealth has traditionally been concentrated in the hands of a privileged few.

This irrational system has been marked throughout Chile’s history by a long, bitter, and often bloody class struggle. On the one hand, the nation’s peasants, miners, factory workers, manual laborers of ail kinds, the many sub and unemployed, the vast majority of the population commonly referred to as the working class, has demanded a larger share of the nation’s social wealth. On the other hand, the nation’s bourgeoisie, the large landowners, industrialists, bankers — those who own and control ail the major means of production and sources of wealth in the country, frequently as partners or representatives of foreign interests — has fought to retain its political and economic control of the society. The middle class — small and medium landowners, small and medium entrepreneurs, clerks, professionals, white collar workers, and public employees — has shifted its allegiance between these two antagonistic classes in accord with how it perceived its short-range interests.

Over the years, the Chilean working class struggle has grown in strength and size. It has evolved from sporadic, spontaneous uprisings to more organized protests and strikes, and from there it has entered the arena of parliamentary politics. As it has advanced, the national bourgeoisie and the foreign interests whose profits depend on the continued economic and political power of this bourgeoisie, have defended their threatened control. To do so they have used a variety of means. Violent repression was one. On a number of occasions it took the form of out-and-out massacres, the most brutal of which was the slaying of some 2,000 striking nitrate miners, port-workers and their families, all unarmed, in the town of Iquique in 1907.

But as the working class, organized in the Socialist and Communist parties, made its way into the realm of electoral politics, the bourgeoisie was forced to change its tactics. If the vote of the organized working class now was strong enough to elect congressmen, the bourgeoisie had to appeal to them in order to win these votes. With practice, the bourgeoisie mastered the art of promising enough to win elections, while leaving the basic structures of capitalistic society intact once they were in office.

The party which proved best at this strategy was Eduardo Frei’s Christian Democrats. In its 1964 presidential campaign, heavily financed by the U. S. and by Chilean conservatives, the Christian Democratic Party promised the electorate a “Revolution in Liberty”. This “revolution” contained many measures traditionally promised by socialism; redistribution of the national income, massive social welfare programs, agrarian reform, banking and tax reform, an end to unemployment and inflation, an attack on monopolies, increased economic independence. All to be brought about in “Liberty — that is, without class struggle.

The Christian Democrats easily won the election. They were supported by the conservative bourgeoisie, who saw the Christian Democrats as a way to keep out the socialists and communists; peasants, who were attracted to the land reform; large sectors of the middle class; and some workers, who had lost faith in capitalism but were taught to fear socialism and were convinced the Christian Democrats offered a “third way”.

In practice, however, the Christian Democrats simply didn’t deliver. Frei promised a lot; but his primary allegiance was to the Chilean upper class. Thus, he did not redistribute income, because that would mean taxing the monopolists. He did not curb inflation, because the industrialists would not voluntarily freeze prices. Instead of nationalizing copper, Frei “Chileanized” it — buying up shares of stock at rates highly favorable to the U. S. copper companies. The piecemeal reforms which actually were carried out mainly benefitted the middle classes, increasing the gap between them and the working class. The reforms, like Frei’s election were mainly funded through the U. S. Alliance for Progress, which attempted to prove that capitalism was indeed flexible enough to provide a substantially better life for the oppressed. Its main accomplishment for Chile was a huge foreign debt — some 4 billion dollars by 1970.

Shortly before his party’s term was up, one Christian Democratic congressman summarized its failure in the following words: “We have a historic responsibility and we have done very little for that 85% of the population which voted for a revolution, while we are making continual concessions to an oligarchy and a bureaucratic minority of 15%.”

By the 1970 elections, Frei’s Revolution in Liberty had been such a flop, that Christian Democratic spokesman edged closer to socialism to hold onto their worker and peasant bases. They spoke carefully of a “non-capitalist” way to development and even of “communitarian socialism”. The only party openly opposed to a sharp break with the past was the conservative National Party (PN), whose sole concern was to defend its members monopoly interests.

Together, the Christian Democrat’s near-socialist and the UP’s frankly socialist programs received 64% of the vote.

Since then, as the UP has tried to implement its program of peaceful advance towards socialism, the Christian Democratic Party has changed its position radically. From its socialist-sounding 1970 campaign platform, it shifted to support the National Party candidates in various local elections, to full alliance with the PN in the March, 1973 congressional elections, to its current position of threatening the government with a military takeover. As the Christian Democrats have shifted to the right, they have lost many of their party members who sincerely wanted change. The first splinter group formed the MAPU party; the second formed the Christian Left (IC). Both parties joined the UP coalition. The U. S. press still calls the Christian Democrats a “left center” party; but if that was ever true, it’s old history now.

The intensification of the class struggle which has split the PDC has, over the course of the past few years, divided the entire country into two camps.

In the remainder of this article we hope to show how this conflict has reached a new stage in all areas of Chilean society: governmental institutions, the economy, the mass media, the armed forces, and the working class.

In short, the rules of the game have been changed.

The Institutional Conflict

Why is there such confusion and instability? On an institutional level, the conflict is primarily the product of the 1970 elections which gave control of the executive branch of the government to the representatives of the working class, peasantry, and poor, while the legislative and judicial branches remained in the hands of the old ruling class.

The UP’s “peaceful transition to socialism” called for a legal process which would gradually turn over control of the nation’s basic sources of wealth and power, held by foreign interests and the Chilean upper class, to the workers and poor. With the unanimous consent of Congress, Allende began to nationalize the country’s natural resources. Using laws already on the books, he brought industrial monopolies and banks into the publically controlled or “social area” of the economy and broke up the large landholdings which were characteristic of the agrarian sector.

If at first the ruling class was too shocked by its electoral defeat to prevent this, it soon re-organized and fought back with all the arms at its command. One of the strongest is the Congress, where opposition parties hold a majority of both houses.

The Congress has been used against the interests of the working class in three basic ways:

I) The Congress has continually removed Cabinet ministers, preventing the government from constructing the stable administrative body which is so important in times of severe economic and political crisis. One justice minister, 2 labor ministers, 2 economy ministers, 3 interior ministers (responsible for domestic security and police), and 1 minister of mines have all been removed from their posts by the Congress on politically motivated and highly questionable charges. Any minister who acts against the will of the Congressional majority — rather than against the Constitution — is likely to lose his post.

The Congress would like to remove Allende, but impeaching a President requires a 2/3rds majority — which they don’t have. Therefore, they remove his Cabinet ministers instead — which only takes a simple majority.

II) The Congress has used its law-making and law-vetoing power to block every major government initiative, destroy the early advances of the UP, and return the economy to the pre-1970 situation. Besides blocking a government proposal to enlarge the sector of the economy in the “social area”, the PDC has proposed a constitutional amendment which would dismantle that sector, returning strategic industries to private hands. Although Allende vetoed the measure, the Congress over-rode his veto with a simple majority, rather than 2/3rds, claiming they had the right to do so, due to a Constitutional ambiguity. As of now, nobody can solve this conflict since the Constitutional Tribunal especially set up to resolve such problems has declared itself incompetent in this matter. This is not a mere legal tangle, however. There are two important issues at stake. One is the creation of a worker-controlled industry through peaceful, legal means — a prime objective of the UP program. The other is the ability of Congress to over-ride vetoes with a simple majority, rather than a 2/3rds majority.

The latter has far reaching consequences. There is no way to settle the 2/3 versus simple majority issue within the Congress and neither side recognizes the right of the same outside authority to decide the issue. Thus, the Congress has reached a virtual dead-lock in its relations to the President.

The Congress badly wants the legal precedent of overruling the President with a simple majority. From such a legal basis, the opposition could proceed as it wants: dismantling the “social area” and shortening the President’s term or impeaching him.

III) Finally, the Congress has fought against the workers and the poor by blocking government projects designed to control the unstable economic situation that the opposition itself has helped to create. For instance, the opposition parties blocked a government proposal to punish speculators and black market operators, thus giving them the full protection of law (or of the Congress) to continue their illegal acts which harm the entire population.

In addition, Congress has refused to appropriate any funds for the UP’s redistributive wage adjustment program and reduced Allende’s budget by 33%. Congressional refusal to finance government programs has forced the administration to print money. Thus, the opposition-controlled Congress is in large part responsible for the rampant inflation which severely affects all workers.

The Congress, with Eduardo Frei — the President of the Senate — as its leader, has established itself as an “anti-government”, which daily presents the government with ultimatae unless all its programs are accepted. A recent statement by the PDC, the largest party in Congress, called for a complete halt to the government’s program and concluded; “If the government does not immediately carry out these tasks, the historic responsibility of what will happen in Chile will fall on its shoulders alone.” (El Mercurio, July 7, 1973) Needless to say, a charge of that kind more resembles blackmail than a responsible action by the largest congressional party.

The Judiciary, too, is flagrantly being used as a weapon of the ruling class rather than acting independently as another “branch of the government”. Justice is dispensed discriminatorily with the interests of the rich, not the poor, always held highest.

We can cite many examples of what this sytem of “class justice” has come to mean. When Moises Huentelaf, a peasant leader, was killed by a landowner during a land takeover in the south of Chile, his murderer was allowed to go free. The 21 peasants involved in the takeover with Huentelaf, on the other hand, were kept in jail for six months. On another occasion, landowners whose land had already been expropriated came back to their former holdings one morning and attempted to rob the machinery which now belonged to the peasants. When the peasants peacefully opposed this, the ex-landowners shot and killed four of them. Again, the murderers were allowed to go free and no charges were pressed against them.

One of the most spectacular cases of “class justice” was that of Robert Viaux, tried and found guilty of planning the kidnap operation which took the life of General René Schneider, Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army, just before Allende took office. The commando operation was planned to create a state of political chaos which would have prevented the peaceful transferral of power to Allende. Viaux first received a 20-year sentence, but this was later reduced to 2 years by a higher court. This term is less than peasants regularly receive for stealing chickens.

In addition to the traditional three branches of government, there is a fourth institutional power in Chile, the office of the Contraloria or Comptroller, which oversees the financing of all government projects. The present Comptroller was appointed to his 12 year term before 1970 when the UP took office. He has greatly amplified the powers of his office, pronouncing on the legality of projects as if he were a Supreme Court.

Thus, whenever industries are brought into the “social area”, the Comptroller declares the move illegal. This means that all funds for these industries are frozen, curtailing plans and destroying production. To override him, Allende must obtain an “insistence decree”, signed by all government ministers. The last time he did this, the National Party initiated Congressional action designed to remove all of Allende’s ministers from their posts.

The UP’s attempt to advance towards socialism by legal means, to use the existing legal system to create new laws benefitting the working class, has run up against a solid wall of opposition. However, the legally stamped documents that rush from one house of Congress to another, from the courts of Justice to the Presidential Palace and from there back to the Congress are not writing Chile’s history. Much to the outrage of the ruling class’s representatives in the Congress, the Judiciary, and the Comptroller’s office, Chile’s history is now being decided in worker-controlled factories and farms and in the community and labor organizations where Chilean men and women are struggling to create a just and non-exploitative society.

The Economy

“Dr. Salvador Allende, similar to Fidel Castro, is conducting his country rapidly to bankruptcy and ruin. ” (Statement from Barron’s magazine, reprinted in El Mercurio, April 20, 1971.)

This statement, published two years ago, is typical of numerous predictions which have been expressed about the UP government since it came into office in 1970. It was written during a year when Chile’s GNP increased by 8.5 percent (compared to an average increase of 4.4 percent during the decade of the ’60’s).

The U. S. press and the Chilean opposition have placed the blame for the presumed Chilean economic disaster squarely on the shoulders of a “socialist” economy. If the UP had not moved Chile to a socialist system — so the argument goes — the economy would still be thriving. There is no doubt that a very severe economic crisis does exist in Chile, but its roots are not to be found in a socialist economy. Rather, the crisis arose when Allende began to dismantle the structures of the capitalist economy, but the Congress and other institutional opposition forces prevented him from putting anything in their place. The opposition demands have become increasingly simple: the government should renounce its commitment to the creation of a workers’ state or suffer the consequences of the economic chaos which opposition forces will (and have) unleashed.

The government’s economic program called for: 1) nationalization of the U. S. dominated mining industry, 2) socialization of key sectors of the economy such as the banks and strategic industries, 3) expropriation of large landholdings, 4) redistribution of income in favor of the working class and the poor in general, 5) lowering of the unemployment rate, 6) reactivation of the economy after severe recession during the final years of the Frei regime, and 7) the redirection of production toward the needs of the masses rather than the upper classes.

In its first two and a half years, the Allende government has managed to accomplish most of these structural changes. The short-term goals were fulfilled through the middle of 1971 since, at the end of the Frei years, there was a good deal of unused capacity in the economy, as well as stocks of goods and raw materials and a large quantity of foreign exchange reserves. Thus, consumption of the lower classes could be increased without major investment and without threatening the high level of consumption enjoyed by the middle and upper classes. After 1971, however, these factors began to disappear. In addition, as the opposition saw its economic privileges threatened, it openly created chaos in the economy by speculating, hoarding, sabotaging production, not investing, and fostering and supporting an extensive black market system.

The United States did not stand apart from this process. While its newspapers predicted disaster in the Chilean economy, the government and U. S. private corporations took steps to produce that disaster. It is no secret that ITT favored “economically squeezing” Chile in order to bring down the UP government. The U. S. government may deny that it accepted this advice, but the facts prove differently. Loans (both bilateral and from multinational organizations in which the U. S. plays a decisive role) were quickly cut off to Chile. Spare parts and raw materials which are crucial to the Chilean economy were withheld. Public and private credits to the government were slashed.

What is actually behind the present economic crisis in Chile? Some ideas can be obtained by looking at the three most obvious symptoms—lack of foreign exchange, shortages of basic commodities, and rampant inflation. The shortage of foreign exchange stems from three economic trends. First, from 1970 until the beginning of 1973, Chile had suffered from a drastic lowering in the world price of copper which supplies over 80 percent of its foreign exchange earnings. Prices on a pound of copper fell more than 28% between 1969 and 1972. Second, the drop in copper prices occurred at the same time that the prices of Chilean imports, especially foodstuffs, went up. And, because of increased consumption of the lower class, the government was forced to import more agricultural products than usual. Even now, with high copper prices, the foreign exchange earnings of copper are not sufficient to cover the increased costs of imports. Third, the loans and foreign investment which have traditionally offset the current account deficit in the Chilean balance of payments (trade balance, shipping costs, plus repatriation of profits by multinational corporations) dropped drastically during 1971. During 1972 and 1973, however, loans from the socialist countries have partially alleviated this problem.

Various factors have created the commodity shortages, none of which has to do with the existence of a socialist economy although there is bound to be some disruption in a transition to socialism. Agricultural production probably will decline in 1973 because the October owners’ strike prevented seed and fertilizer distribution, and bad weather conditions damaged the crops. Industrial production is also down this year because of lack of investment by the private sector over the last two years, lack of raw materials and spare parts (aggravated by the foreign blockade), and sabotage in the factories. In addition to production problems, there are also distribution problems since the government controls only 30% of food distribution. A good deal of the part controlled by the private sector goes directly to the black market where prices are so high that the majority of the Chilean population cannot afford to buy through this channel. It is not uncommon, for example, to see upper class Chilean women selling chickens from the trunks of their cars in the upper class neighborhoods of Santiago for five and six times the official government price. With its still large profits, the opposition has invested in speculation rather than production. These speculators purchase everything from cigarettes to houses and sell them a few months later for two or three times their purchase price.

The third sign of economic crisis is inflation. This, too, is based on the middle and upper classes’ political opposition to Allende rather than being the natural result of a socialist economy. Major causes of the inflation are the objective lowering of production due to the factors mentioned above, a thriving black market, and the government’s liberal recourse to printing money. This latter factor is important to understand. The government has been forced to print money for one basic reason: the Congress has refused to authorize financing for many government projects including wage readjustments to make up for increases in the cost of living. Any project which is financed by increased taxes on the upper classes, e.g. taxes on corporate profits, high incomes, real estate value of second and third homes, is immediately blocked by the Congress. Opposition congressmen see themselves as egalitarian; rich and poor should be taxed equally; if the wages of the workers are raised, the salaries of the wealthy should be increased proportionally.

The opposition prefers the traditional way out of the supply and demand problem implied in the inflation: lower demand by raising prices to the point where the lower classes cannot afford to pay them. The government, however, is pledged to protect the level of consumption of the masses. Given the structure of the Chilean economy and its position within a world economic system, it is totally unrealistic to think that the economic status of the Chilean masses can be raised while the middle and upper classes maintain their same privileged level of consumption.

The left is basically agreed on the solution to these economic problems. The recent Congress of the UP made a series of recommendations: broaden government control of the economy by bringing the rest of the major production and distribution firms into the social area; finish expropriation of all landholdings over 40 hectares and include the farm machinery and livestock in the expropriation; ration essential consumer goods; restructure wage patterns to produce equal pay for equal work; increase the effectiveness of government planning; and increase the participation and control of the mass organizations in the economy. The main problem is that in order to carry out these goals, the UP must increase its political power. Resolution of Chile’s economic problems depends, to a large extent, on the prior resolution of the question of political power.

Mass Media

An important distortion which regularly appears in the U. S. news media is that the UP government is determined to destroy freedom of the press in Chile; that it is economically and politically stifling the opposition’s news media.

A quick glance at a corner newstand or brief exposure to an opposition radio station clearly indicates the contrary. There is probably no country in the world at this point in which the opposition press bombasts the government in power with such vindictiveness as in Chile. Headlines range anywhere from one declaring the country to be on the verge of total economic collapse (this only a few weeks after Allende took office) to a recent headline in the National Party’s paper, Tribuna, which demanded that those military officers responsible for putting down the attempted coup of June 29th be tried and punished.

And, if the level of insult is astonishing in the press, radios are far worse. In the first minutes of the recent coup, Radio Agricultura, owned by the national association of large landowners (SNA), proclaimed the coup to be “without doubt a definitive move to bring about the changes which the majority in this country has been waiting for.”

Cold figures also refute the contention that the voice of the opposition is being squelched in Chile. The opposition still owns the vast majority of the nation’s radio stations—as a quick run down the dial will prove—and six daily Santiago newspapers with a total weekday circulation of 541,000 copies. Pro-government groups and parties publish only 5 Santiago dailies with a circulation of 312,000. In the provinces, the opposition press is far more widely distributed than the pro-government press.

However, the publicity given to the “freedom of the press” issue serves an important purpose. In the first place, accusations that the government is infringing on this freedom are quickly picked up by the international press. A headline stating that “Opposition Parties Claim Allende is Curbing Press Freedom” misinforms millions of newspaper readers around the world. Secondly, by constantly pretending to be under attack itself, the opposition press distracts attention from the unprecedented way in which it attacks the government. Standard legal norms such as libel can no longer be applied to the opposition press without setting in motion a worldwide furor.

The ruling class has always employed its vast mass communications resources in defense of its own interests. In ordinary times, when the bourgeoisie is solidly in power, it may do so without resorting to sensationalism. The “establishment” press, in fact, cultivates a sober, polished style which in itself conveys the impression of “responsibility”. But when the interests which it represents are under serious attack, as is now the case in Chile, this stylistic veneer of “objectivity” dissolves, and the press reveals itself for what it basically is — an immensely important political weapon.

As a case in point, we can take El Mercurio, owned by the wealthy Edwards family. Agustin Edwards, the paper’s publisher, left Chile when Allende was elected and is now serving as a vice-president of Pepsi-Cola in Miami. As the ruling class came under greater pressure from the workers, Mercurio lost its traditional “calm”. With each issue it has become easier to see in whose interests the paper is written. Mercurio is a good example to pick since the New York Times (June 25, 1973) sees fit to call it a “conservative but widely respected Santiago newspaper.” Our guess is that the Times never bothered to ask a Chilean worker whether he or she “respects” El Mercurio. The answer would be “no”.

The use of the press as a political weapon is not simply a matter of the size of headlines or color of the vocabulary. Through distorted and alarmist reporting, the news media can create economic chaos and bring a-about political havoc. It moves past “reporting” the news to making the news. For example, it is enough for El Mercurio to state that there is a shortage of toothpaste one day for there to be a shortage the next. After reading such reports, people immediately rush out to purchase as much of the item as possible thus, obviously, creating a shortage which did not exist the day before. This has been done not just with toothpaste, but with bread, coffee, powdered milk, baby nipples, and other items whose lack is keenly felt by the entire population.

On June 23, the New York Times ran an article with the headline, “Court in Chile Shuts Paper Over Anti-Allende Ad.” There is a two-fold implication here — that the ad was merely a statement of opposition to Allende, and that the government has the ability (and desire) to shut down the press for such an offense. The ad, run by the National Party, in fact called on Chileans to reject the government as “illegitimate” and “unconstitutional” and, further, to disobey all measures the government might propose — nothing less than an open call to insurrection, something quite different from an “anti-Allende ad”. The government filed suit to close the paper for six days, not indefinitely as the Times implied, and the courts opened it again after just one day of closure.

Actually, this was somewhat of a victory for the government, at that. Of the approximately 50 suits it has filed against openly seditious use of the news media by the opposition, it has won almost none. The reason is simple: the courts are headed by staunch members of the opposition who guarantee the wielding of this powerful political weapon in the hands of those so desperately resisting change.

The Armed Forces

” … politicizing the military could be disastrous for Chile’s durable democratic system … ” New York Times, editorial, early 1973.

“Under the watchful eye of the traditionally non-political armed forces, Chile’s democratic system has survived … ” New York Times, editorial, April 3, 1973

On June 29th at 8:40 A.M. tanks of the Chilean Army’s Second Armored Regiment in Santiago rumbled out into the streets and set course for the Presidential Office Building. The rebel regiment fired on the “Moneda” for three hours before surrendering to Army Commander-in-Chief, General Carlos Prats. Other coups have been planned during the last three years, but this one actually reached the streets. Once again, it shattered the myth that Chile’s armed forces, traditionally, have been nonpolitical. As with all else in Chile, the deepening political and ideological crisis of the ruling class is pushing the armed forces into the center of an intensifying class struggle.

The phrase “non-political military” can mean two things: 1) a military which does not intervene in the administration of the State, or 2) a military which holds no political opinions — a “professional” force which stands above politics. It is quite possible to have a State in which the military is non-political in the first sense; it is impossible to find a State where the military is nonpolitical in the second sense. Neither case holds in Chile: the military has taken an active role in the administration of some areas of the State economy, and the vast majority of military personnel hold political opinions.

Prior to the presidential elections of 1970, the Chilean armed forces intervened in the nation’s political processes in two important ways. First, they actively intervened on behalf of the ruling class in the inter-class struggle by repressing many protest movements of the working class and poor. The bourgeoisie called in troops to put down the 1907 I qui que strike. More recently, the armed forces were used to crush protest movements in Santiago (1946: 8 killed, and 1957: 18 killed), El Salvador (1966: 8 killed, 37 wounded), and Puerto Montt (1969: 9 killed, 30 wounded).

Secondly, the armed forces have been used by various sectors of the ruling class in the intra-class struggle when all other methods of conciliation had failed. In the twentieth century alone, there were successful military coups in 1924, 1925 and 1932. Each represented an attempt of one sector of the ruling class to displace another sector from a position of power.

The picture changed fundamentally in 1970. If the pre-1970 armed forces could play the “constitutionalist” role of upholding the political system, this was no longer the case following the electoral victory of the Unidad Popular. All three branches of the government, until 1970, were controlled by the same class — all three branches protected the same interests. Now, however, with the executive branch of the government in the hands of an administration which represents the working class and the legislative and judicial branches still controlled by the old ruling class, the matter of determining just what is “constitutional” gets increasingly difficult.

The Chilean military is not a monolithic institution. It, too, is composed of the classes which make up Chilean society in general. The majority of high ranking officers, according to a recent sociological study, come from upper class or upper-middle class families. Most middle ranking officers tend to come from the middle class, and the majority of the lower ranking officers, recruits and the conscripted soldiers and sailors originate in the peasantry and industrial working class.

Furthermore, the orientation and composition of the Chilean armed forces has been heavily influenced by the United States. In 1947, the U. S. and Chile signed the “Inter-American Mutual Defense Treaty” designed to extend U. S. “protection” to Latin America in case of communist “attacks”. When the U. S. Military Assistance Program (MAP) began in 1952, Chile quickly became one of the prime recipients of U. S. military aid on the continent. Between 1950 and 1965 over 2,000 Chileans received training in the United States as part of this program, more than any other Latin American country with the exception of Brazil and Peru. Chile received the highest per-capita amount of military aid in Latin America between 1953 and 1966.

When the Unidad Popular took office in 1970, the class struggle obviously intensified, and this struggle continues to remain the dominant theme underlying present crises in all areas of Chilean life. But, the victory of the UP also aggravated the struggle for leadership among the different factions of the ruling class. The Attempted coup of June 29 demonstrated how deep the roots of the class struggle in Chile actually are: but, it also demonstrated that the Chilean ruling class is divided, for its failure called attention to the fact that the ruling class has not been able to decide when or how to use the armed forces to protect its interests.

Just as there are two dominant tactical positions in the Chilean Right, reflected in the positions of the National and Christian Democratic Parties, there are also two anti-UP trends within the military hierarchy. A minority sector believes that a military coup followed by a prolonged period of open military dictatorship is necessary if they are to regain full control of the State and protect their economic interests. This group is willing to risk open civil war and the consequent rupture of military hierarchy and institutionality. This is the faction that acted June 29th and is supported by the fascist “Fatherland and Liberty” movement and the reactionary National Party.

A majority of high ranking officers believe that some form of open political intervention is necessary, but want to do it in such a way as to preserve their institutional interests and avoid a prolonged period of outright military dictatorship and civil war. This is the so-called “constitutional Right” which reflects the Christian Democrats’ desire for a “constitutional coup” that would install a temporary caretaker government until a Christian Democratic president (presumably Eduardo Frei) could be elected.

There is also a third group of Left Constitutionalists” composed of high-ranking military officers who believe that since Salvador Allende was elected to a 6 year term of ~ffice, no movement could remove him from office before 1976 and still remain constitutional. General Prats , Commander-in-Chief of the Army, is included in this group.

Among the soldiers and sailors themselves, though, the situation is different. A trend towards the Left may well develop as workers and peasants identify with other members of their class. Shortly after the unsuccessful coup of June 29, a group of high-ranking officers in the southern city of Valdivia began preparations for a new coup to overthrow. Allende. They were opposed and finally denounced by the low-ranking officials and the soldiers. Also, one now frequently sees smiles of approval on the faces of many soldiers when the Left chants, “Friend, soldier, the people are with you!”

These experiences may influence the armed forces’ final allegiances. Clearly, though, the military in Chile can no longer be conceived as neutral; neither can they be expected to act as a unified institution.

The Workers

“Much of the labor force is striking against the government for higher pay. A prime example: the copper workers at El Teniente … ”

James Nelson Goodsell in the Christian Science Monitor, June 25, 1973“The copper strike is the first bitter confrontation between blue-collar workers and the two and one half year old government, which has championed workers,”

Jonathan Kendell in the New York Times, June 16, 1973

The accusation appears over and over again in the U. S. press: the UP — the workers’ government — has turned against the workers. The reporting on the recent El Teniente strike was important since it called into question the fundamental social basis of the government: if the workers had abandoned the government, who remained?

The roots of the Teniente strike are complex, but they deserve to be explained. Teniente is the largest underground copper mine in the world. As such, it plays a tremendous role in the Chilean economy which receives over 80% of its foreign exchange earnings from copper sales. The copper miners are well organized and have a long tradition of struggle for decent living and working conditions. Unlike most Chilean workers, they were able to win significant economic battles before the UP government took office.

Because the copper mining industry is so profitable, the U. S. companies operating the mines before 1971 were able to offer the miners higher wages and benefits and still maintain what they later admitted to be an average rate of profit over 50% a year.

Furthermore, the owners were aided in their dealings with the miners by the historic division that has existed within the Chilean working class: that between “obreros” and “empleados”, a division roughly corresponding to the blue-collar/white-collar distinction. In Chile, this division has been given a certain legal recognition and has resulted in the establishment of two different legal minimum wages, two separate sets of unions with two separate contracts and with different benefits. Politically, the “obreros” have always stood close to the Communist and Socialist Parties while the “empleados” were divided between the former and the Christian Democrats.

What, then, are the facts of the strike which didn’t appear in the U. S. press?

1) The New York Times (June 16) reported that the miners struck for a 41% raise as part of a nationwide wage increase approved by the legislature last year. In fact, the government has granted all workers 100% across the board wage increases for a cost of living compensation. Yet, the opposition argues that since the miners already had an automatic 50% readjustment for inflation written into their private contract, they were entitled to this plus the 100% increase in the government bill, i.e., 150% rather than the 100% granted to all workers. Copper miners, it should be noted, already receive at least 4 times the average industrial wage. A discriminatory wage increase in their favor would only raise this ratio higher. The government, opposed to increasing the wage differential between workers, obviously could not accept this measure. Nevertheless, the opposition argued that the mining and labor ministers were breaking the law by not granting 150%. So the Congressional opposition removed them from office. The strike came to an end when the remaining sectors of striking miners accepted the identical proposal that the mining and labor ministers had made seven weeks earlier.

2) The Christian Science Monitor (June 25) reported that “much of the labor force” was out on strike against the government; most other newspapers reported that 12,000 workers at Teniente were on strike around the same time. There are 12,750 workers at the various mines and foundries of the Teniente complex. In June, at least 70% of the total work force at Teniente was on the job and over 90% of the “obreros” were working. The strike found its strongest support in the white-collar workers, largely controlled by the PDC, and not in the blue-collar workers. There were no other major strikes involving large numbers of workers at that time.

3) Most papers reported wide backing for the strikers, implying that few people actually supported the government position. In fact, the support which the strikers did receive was so uncharacteristic that it clearly belied the opposition’s position that this was an economic, not a political, strike. Never in the long history of the working class movement in Chile has a workers’ strike received the support of the national organization of large landowners (SNA), the national organization of large industrialists (SOFOFA), the national organization of merchandise distributers, the Chilean doctors’, lawyers’ and engineers’ associations, the conservative National Party and the fascist “Fatherland and Liberty” organization. On the other hand, none of the large workers’ organizations favored the strike, and no other miners’ union, regardless of U. S. and Chilean opposition press reports, joined the walkout.

Clearly, the strike was politically, and not economically, motivated. The political motivation developed from the failure of the owners’ strike in October, 1972. During this strike, 99% of factory workers (blue and white-collar) remained on the job and many, along with students, did voluntary work to counteract effects of the strike. The opposition realized that if they were to bring the country effectively to a halt and, thereby, justifying military intervention in the government, they would have to divide the working class. That’s what they tried to do with the El Teniente strike. As one El Teniente worker said: ”Those who claim to be defenders of the workers are provoking an enormous conflict between workers. They are creating hatred between workers, and this has never existed before.” The PDC union leaders at El Teniente went to the other large copper mines to try to generate sympathy strikes, while the PDC and PN press urged all workers to strike in sympathy of the 150% wage increase for the El Teniente miners. As already pointed out, their efforts failed and the strike at El Teniente slowly petered out.

The working class remains the social base of the UP government. During the period between the elections of 1970 and the present they have led the battle to break down the old ruling class and build a socialist society in Chile. The most important advances have been in the creation of the seeds of popular power: worker control in over 300 socialized factories, peasant control of farms encompassing some 40% of farmable lands and neighborhood control of food distribution in working class districts. The process is still new and much remains to be done: but each new crisis sees the working class advancing with great determination. During these periods the workers demonstrate an ability to learn and to organize themselves that often surpasses that of the UP government.

During the owners’ strike of last October, for example, two new forms of popular power sprang up: the “Cordones Industriales” and the Communal Councils. The “Cordones” are based on the industrial workers who are concentrated in various “bands” of large factories that surround Chile’s major cities. The Communal Councils are coordinating organizations which, in addition to the representatives of factories and farms, include representatives of all community groups (women’s organizations, food distribution co0peratives, students, etc.). Both are broadbased organizations composed of elected representatives which decide basic policies from defending the factories against right-wing attacks, to pressuring the government for the socialization of new factories, to the distributing of primary necessities in their areas.

The workers are the driving force behind the UP government and they have continually demonstrated their desire and commitment to establish a socialist society in Chile. When the New York Times (editorial, June 25, 1973) recommends that Allende “stand up to the radicals in his own ranks”, it somehow forgets that the “radicals” are his ranks.

The United States and Chile

The Senate hearings on ITT’s activities in Chile showed that U. S. corporations and government officials worked to defeat the Unidad Popular in 1970 and tried to prevent Allende from taking office after he won the presidency. Since then, U. S. banks, corporations, the press and government agencies such as the CIA have sided with the Chilean upper class. They have acted in many ways to paralyze and discredit the Unidad Popular:

1) U. S. copper companies, especially Kennecott, have attempted to block Chilean shipments of copper to Europe, thus cutting off a vital source of foreign exchange to the country. Kennecott claims they have not received “just compensation” for their nationalized mines in Chile, even though since 1955 their average rate of profit on invested capital was 52.8% (Their average rate of profit in other countries where they own mines is 10%).

2) The U. S. Eximbank curtailed all loans until the question of compensation for U. S. mining and other interests has been resolved.

3) U. S. private banks also curtailed loans. By last year, only $35 million in short term credits were available from private banks as compared to about $220 million in past years.

4) Almost all suppliers cut off credit.

5) U. S. A.I.D. cut off loans to the Chilean government (although AID programs continue to train opposition labor, business and political leaders in their schools in the U. S.).

6) The World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank curtailed their loans to Chile. Both these multi-national lending agencies are dominated by the United States.

7) The United States tried to pressure European creditors (“The Paris Club”) into forcing Chile to immediately pay its foreign debts. The vast majority of these debts were contracted long before Allende took office.

8) Private U. S. corporations curtailed all credit for shipments of replacement parts to Chile, thus effectively denying the nation these items.

9) Various CIA agents acting in Chile are implicated in the activities of openly seditious groups. Keith Wheelock, for example, a CIA agent who “officially” held a post at the U. S. Embassy in Santiago shortly after Allende was elected, served as the contact with the fascist “Fatherland and Liberty” movement. Neither is U. S. Ambassador Nathaniel Davis above suspicion. Davis was previously ambassador to Guatemala during the period when U. S. diplomats and military advisors helped the dictatorship organize fascist terror groups such as “White Hand”, “New Anti-Communist Organization”, and the Anti-Communist Council of Guatemala”, which murdered thousands of Guatemalan students, workers and peasants. Davis was transferred to Chile shortly after Allende was elected to office and brought a large “political” staff with him from Guatemala.

10) U. S. dollars have supported opposition strikes, such as the October owners’ strike when truck owners were paid to stop transporting goods and offers were made to pay workers if they stopped producing. U. S. funds were also used in the 1964 and 1970 election campaigns — both times against Allende.

11) A manifestly anti-Allende press campaign has been conducted in the major U. S. newspapers and other media. The U. S. press has blamed the Unidad Popular’s “Marxist-dominated coalition” for bringing about the present crisis. As a June 25 New York Times editorial said:

” ‘Civil war must be avoided,’ declares President Salvador Allende; but his Marxist-dominated coalition perseveres with policies and tactics certain to accelerate the polarization that has pushed Chile close to the brink.”

It is true that Chile is deeply polarized. But the Times has not written editorials against the Congressional opposition which has blocked every government proposal designed to help the workers. Or against the Christian Democratic youth groups who burned Socialist and Communist Party headquarters. They have not criticized the Christian Democratic congressmen who have refused to talk with the government (even though the latter has shown itself willing) unless the UP totally discards its program. Or the leaders of the National Party, who have threatened Chileans with a civil war unless its demands are unconditionally met.

This type of coverage in the U. S. press is guided by an implicit assumption: that the Chilean upper class is justified to defend its interests by any means necessary; and that the Chilean working class and peasantry should yield graciously.

The left parties in Chile conscientiously explored a new road to social justice — the via Chilena — which was intended to provide a peaceful transition to socialism. This road was blocked by the upper class, using its congress, its courts, its economic power and, most recently, cooperative sectors of the armed forces. In President Allende’s words, “It is not the fate of the revolutionary process which hangs in the balance. Chile will inevitably continue its march towards socialism. What the fascist opposition threatens is the completion of this process in accordance with our historical tradition, without the use of generalized physical violence as an instrument.”

The U. S. people should know these facts: we should know the role of our government in the events which are currently developing in Chile. And we should oppose any and every action taken by the U. S. against the Chilean people.

QUICK COUP OR SLOW STRANGULATION

During the days immediately following the successful counter-revolutionary take over by the fascist military forces in Chile, charges and counter-charges about the involvement of the United States in the events were bitterly exchanged in the press and national media. Thus, the New York Times reported in its first article: “U.S. Not Surprised” in a headline on Sept. 12 and repeated on Sept. 14: “U.S. Expected Chile Coup But Decided Not to Act”. Most of these stories concentrated on specific events and actions in which the U.S. did or did not have a hand. But the point is not the precise way in which the U.S. is involved with particular counter-revolutionary forces, it is rather the pervasive influence of U.S. economic policies on the internal political situation in Chile and their impact on the whole of Chilean society and economy.

Direct involvment dates back at least to the beginning of this century when U.S. capital took over control of one of the largest Chilean copper mines from the Chilean government. The U.S. supported Chilean government which encouraged the growing wave of foreign investment and permitted the importation of consumer goods which transformed the country from an economy which exported food into one incapable of even producing sufficient food for its own population; by the time the UP (Popular Unity) government was elected to power in 1970, more than one-fifth of all domestically consumed consumer food stuffs had to be brought in from abroad because the high concentration of land, past agricultural policies and U.S. aid programs prevented an expansion of production in this area. In place of agricultural production, Chilean economic policy substituted an import-substitution industrialization program designed to produce light industrial consumer goods and to strengthen the budding base of heavy industrial production which was largely in foreign hands; these efforts largely benefitted the upper and middle classes who had the income to enjoy nonessential consumption goods. In spite of a large presence of U.S. private investment, however, the economy continued to experience serious bouts of inflation and economic stagnation ( prices increased by more than 25% in 13 of the 18 years prior to Allende’s election while per capita income remained virtually stagnant).