This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Actions at Imperial Science Meeting in Mexico

by The Midwest contingent of the AAAS/Mexico City Action Group

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 5, September 1973, p. 10 – 23

The following article describes Science for the People actions and activities at the recent joint meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). The article was written by part of the SESPA/Science for the People group which journeyed to Mexico to join Mexican students and workers in opposing the role of U.S. imperialist science and technology in Latin America and to work toward building an international alliance of anti-imperialist scientific and technical workers.

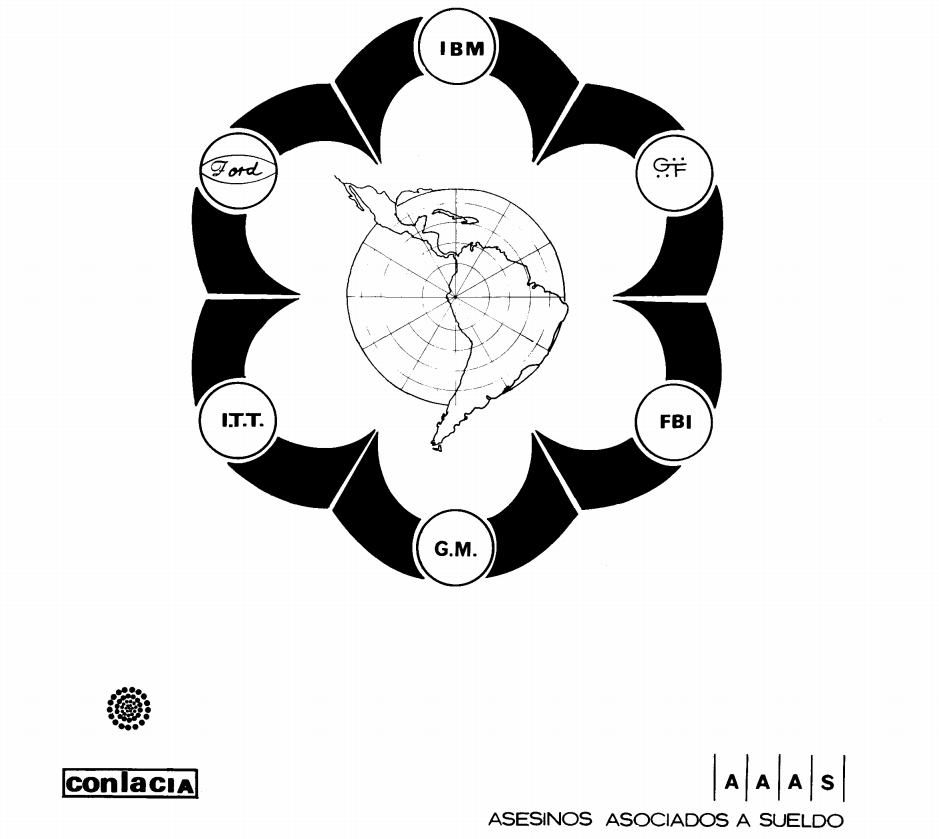

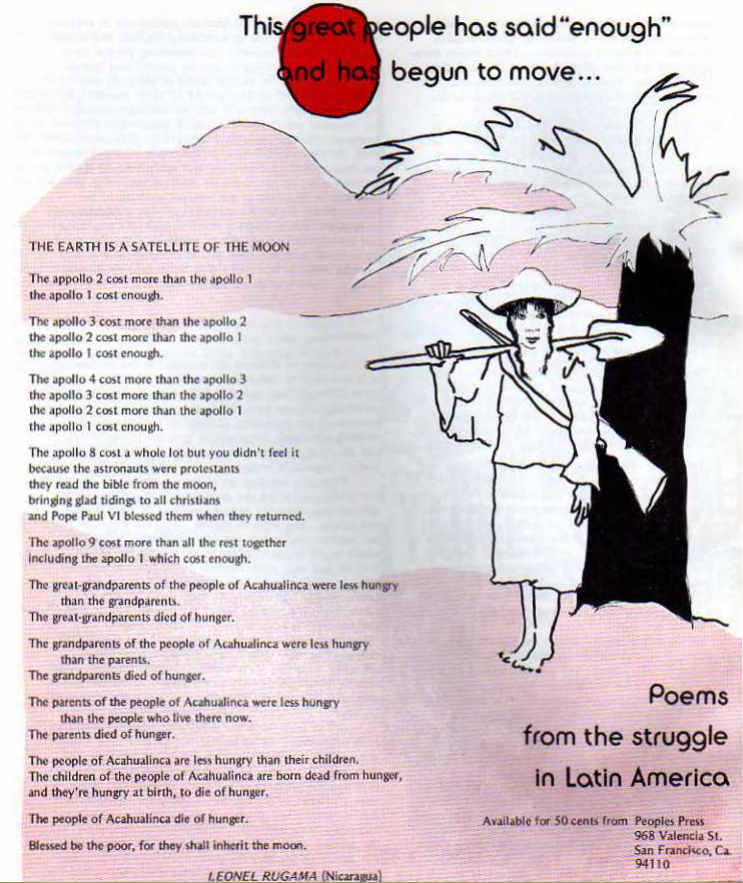

The poster on the next page, created by a group of Mexican students, is a take-off on the official AAAS/CONACYT insignia (see below). It announces an Intercontinental Meeting on Science Against (Contra) the People, substitutes CONLACIA (with the CIA) for CONACYT, and refers to the AAAS as the Association of Paid Assasins.

In Preparation

For Science for the People (SftP) it all began December, 1971 at the AAAS meeting held in Philadelphia. Some of us discovered an unpublicized symposium of Latin American and other Third World scientists. Apparently, this was to have been a preview of the Mexico meeting, but unfortunately for the AAAS, the scientists there distributed a declaration denouncing U.S. imperialism in no uncertain terms. It goes without saying that they were not invited afterwards to participate in the AAAS/CONACYT meetings of June, 1973 in Mexico City, so sexistly entitled “Science and Man in the Americas.”

SftP began to prepare for its own equally-uninvited participation in August, 1972. Our first step was to make contact with friends in Mexico. It was through some of them that we later received so much help and support. We also corresponded with numerous Latin American scientists in the hope of using the meetings to come together to create an anti-imperialist scientific community in Latin America. (The fact that very few Latin American scientists came to the Mexico meeting has delayed this plan.)

Our next step was to prepare a lengthy statement on science and technology in Latin America, entitled AAAS in Mexico: Por Que? (Why?). This was to serve both as a primer for uninformed U.S. scientists and as a vehicle for the clarification of our own position on the Mexico City Meeting. This turned out to be a tremendous effort (a 32-page booklet) that lasted from October to the December, ’72 AAAS meeting, where Por Que was distributed and where we put a major emphasis on the upcoming Mexico City Meeting.

SftP groups in Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Puerto Rico began organizing. Copies of Por Que were sent to friends in the U.S. and Latin America, correspondence was initiated with possible participants, especially with Latin American scientists and Latin American students in the U.S. We also translated Por Que into Spanish, an effort that again involved many people and which put us into debt.

The last stage of preparation took place in Mexico. Four people went to Mexico to improve their Spanish, to find accommodations and to make the practical arrangements for our meetings. More important, one of them made contact with the left, the press, and the students. Out of this came the cooperation of militant students from the Universidad Nacional Autonomo de Mexico called the UNAM: National Autonomous University of Mexico), arrangements for a T.V. program, and a press release in Punta Critico, a Mexican left monthly magazine. (A planned press release to a variety of left publications in Latin America was never followed through.) Some of the counter-Meeting sessions at the University were planned and lots of our literature was distributed before the rest of us arrived in Mexico, just as the President of Mexico, Luis A. Echeverria, was officially opening the conference with the standard speech of welcome.

How the Cry of BULLSHIT! was Heard in the Land

On the first day of the conference our attempt to distribute a leaflet on the Jason Committee1 at a physics panel was thwarted. Marcos Moshinsky, chairman of the panel and a leading Mexican physicist informed us that that was done in the U.S. but was not acceptable in Mexico. But our first face-to-face encounter with the organizers of the meeting themselves came the next day. Jim Cockcroft, economist at Rutgers, had been originally scheduled to talk at the Technology Transfer panel. When his anti-imperialist politics were understood his invitation was withdrawn. Then at the last minute he was taken on as a discussant for the same panel. But in the course of Cockcroft’s denunciation of the imperialist aims of technology transfer, the chairman of the program, a representative of Rockwell International, cut off his microphone without any warning and pretended that Jim had overrun his time. This barefaced censorship with its mere excuse for a rationale was too much for us, and a resonant cry of BULLSHIT! came out from one of our more soft-spoken comrades. This had two results. At the end of the meeting, the chairman, in an attempt to regain his image of impartiality, asked Jim if he wanted to answer any further questions. Jim’s reply was that what he wanted was to finish what had been so rudely interrupted.

Secondly, immediately after the meeting we were approached by a CONACYT (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia: National Council of Science and Technology) official. He was all amiability. CONACYT, he maintained, was not the AAAS. It wanted to avoid trouble and to guarantee our democratic rights. In fact, if truth be told, it secretly agreed with many of our political positions. He offered to provide us with a table for our literature with a room for our talks, offered to do the publicity for our sessions and to smoothe the way if any difficulties arose. But the only price for this was our good, temperate, and civilized behavior and enough discipline not to be provoked.2 With the astuteness of a confirmed bureaucrat he decided which of the members of SftP were “significant” and directed all of his conversation to these two.

FAN MAILDear Dr. Greyber [AAAS Meeting Manager] : I am glad that I had an opportunity to talk to you ant the AAAS general section session in Mexico City. My motive in attending was to find out how AAAS programs get launched and possibly add my two cents’ worth. My feeling is that, in spite of valiant and meritorious efforts, AAAS has not yet got down to the nitty-gritty of the role of science in our society. … [The AAAS] shows a dangerous resistance to criticism and new ideas. AAAS has consistently,, through reports in Science, put down radical science groups claiming that their sole purpose is disruption. I can testify from firsthand experience that this is false and I think a deliberate misrepresentation. The fact is that groups like SESPA have. a reasoned case M.G. |

The image he put forth was one of a basically good guy in a compromising position who would do his best against an array of nasty bureaucrats outside his control. The only qualification he put forth was that he was powerless against Mexican law, and we should work within the legal system. We assured him that the Mexican constitution provides us with more than enough rights. With a comradely pat on the nearest knee and a man-of-the-world smile he acknowledged the compliment, but begged us not to push it too far.

Thou Preparest a Table Before Me in the Presence of Mine Enemies

We then went on with our work. We appropriated a table in the lobby where we displayed AAAS in Mexico: Por Que? in Spanish and English, back issues of Science for the People, and leaflets written for the conference; we also announced counter-Meeting talks.

The table quickly became a center of attention and activity. Pigs came by to look themselves up in Por Que; out-of-touch radicals came by to make contact and offer greetings. People came to us to complain about the quality of the conference panels. There were inquiries about particular topics, such as science teaching. As the only focus of dissidence, we were approached by people wanting to sound off, express sympathy, or just find intelligent conversation. But mostly we met and spoke with Mexican students to whom Science for the People was new and exciting. The students had a clear, good, anti-imperialist line. Our position on the uses and aims of imperialist science led to sympathetic recognition, but what really excited them was our less-familiar analyses of class content in the internal organization and content of science. These discussions led to additional invitations to speak at various faculties of the UNAM and at other centers in Mexico City. In the end most of our speaking took place away from the Meeting. In the highly political environment of the Mexican student movement, minimum publicity with short notice still attracted up to several hundred students at a time. We always talked to large and friendly audiences.

The literature table ran into one snag. There were various attempts to stop us setting it up in the morning, and once a full-fledged attempt to stop us from selling anything at all. The building we were in, we were told, forbade any sort of selling whatever. But a quick survey discovered a Hertz rent-a-car counter, a tour agency, photograph sales, and book sales, including a AAAS booth. When our friendly CONACYT agent came by to apologetically pressure us to stop selling, we had our list ready. This stopped him in mid-cajole. With nothing to say, he said nothing, and didn’t darken our doorstep again.

People coming to the table told us they thought the literature [which included the leaflets described in box on this page] was high quality. After the first few days, however, two questions came to haunt us: “Did we have any more copies of this piece of literature?” and “Did we have any new literature?” Any fears we had of being ignored were dissipated. In response to the demand for literature, we reproduced more copies of the leaflets and also did some translating of our material. But it wasn’t enough; by the end we were virtually out of every item.

In addition, we distributed literature at the various talks we gave around the city. Especially when speaking to these groups, we consistently underestimated the demand. During one talk, we received 20 requests for Our Bodies, Our Selves3 after a mere mention of the book. We were also overwhelmed by requests for buttons. (The symbol on the button found its way onto many posters produced by the Mexican left. They pointed out that a left fist instead of a right one would have been more appropriate.)

Civil War

The counter-conference sessions organized by SftP took place in an unused room without the benefit of simultaneous translation. The sessions were bilingual, with speakers or volunteers from the audience translating the talks and discussions. The first session, entitled “The Civil War in Science”, was an introduction to Science for the People and our introduction to the Mexican political scene. We emphasized that it wasn’t we who introduced politics into science, but that science was intrinsically political. We pointed out that the politics of science are invisible only when they are establishment politics. In another session, “The Automobile, Vehicle of Technological Imperialism”, David Barkin, a radical political economist, showed that developing underdeveloped countries could not afford the wasteful investment in an auto industry, which ties up labor, material, and technology, and which imposes the obligation to develop gas stations, mechanics, highways, etc., for the benefit of the very few. A third session was “Toward a Socialist Science”, which drew on the experience of our members with the science of Cuba, Viet Nam, and China to show that what is “natural” in capitalist science is not inevitable. We challenged the notion that humanity is necessarily divided into those who create knowledge, those who transmit it, and those who use it. This session was followed by another on professionalism. The experience of the Madison SftP’s investigation of the Army Math Research Center was used to illustrate several points of professionalism: the myth of neutrality, specialization and ideas of expertise, mystification of language, and separation of scientists from the People. Professionalism was also distinguished from competency. Another session, “The Strategy of Agricultural Research”, undermined the notion of the efficiency of U.S. agriculture. It showed U.S. agriculture to be wasteful in energy consumption, soil nutrients, and resources, although narrowly efficient in terms of yield per man hour or per acre. The research of green revolution plant breeders was criticized for its narrow empiricism, lack of theoretical content, indifference not only to social consequences but also to ecology. A strategy of dispersed research as a mass phenomenon as in China was offered as an alternative to the elite international gene factories.

SUMMARIES OF LEAFLETSA leaflet produced by the Minneapolis collective and directed at a specific session of the Meeting with the same name was titled “Science and Human Values”. It pointed out that the division of labor that assigns small portions of large problems to specialists within science leaves the decision-making involving application to those in the higher echelons of government and industry and leaves human values completely outside the domain of scientists. It explained that the export of this science carries with it cultural and political values, and is completely divorced from the people’s real scientific, technological, and political needs. A second leaflet, “Supplement to the Symposium on Tropical Ecosystems: the Use of Puerto Another leaflet, prepared by a group of medical students at the UNAM, dealt with psychosurgery, in answer to the official session on behavior control. It related how psychosurgery, a technique to cut out violence (and creativity, and the capacity for reflection) through brain surgery, is being developed as a crime-fighting tool in the U.S. The leaflet pointed out that racial minorities and political prisoners are the main victims of this new program, which represents a further move toward facism by the U.S. government |

Our final session was held to make plans for continued cooperation between Mexican and U.S. scientists and to give a final overview. It dealt largely with an analysis of the nature and implications of guerrilla science [see box].

GUERRILLA SCIENCEGuerrilla science, organized around independence movements, is directly part of the people’s |

These counter-sessions at the meeting started with about 40 people and grew to about 100. Discussion and questions led from the presentations to the problems and experiences of the audience. For example, there was lively controversy about the medical curriculum. In a counterposing of quantity and quality, some felt that a shorter course of study would produce more but less qualified doctors, while others argued for maintenance of the quality while increasing the numbers of medical students. Some questioned whether the insistence on quality while there was no medical care available for so many was not an elitist luxury. We learned that much of the medical curriculum consists of the transmission of the kinds of U.S. pharmaceuticals prescribed for the familiar illnesses of the affluent. The upshot was the recognition that you could not solve the contradiction between specialized and mass medicine in the individualistic context of contemporary medicine. The discussion ended in a deadlock that reflected the real incompatibility between high quality medical training and large-scale public health service within capitalism.

Go Forth from This Conference

We obtained a number of speaking invitations from our preliminary contacts and from new contacts we made at the AAAS/CONACYT meeting. These invitations came mostly from radical student groups, but in a few cases we received requests to speak before workers’ groups and high school students.

Initially, the speaking duties landed on the person who was fluent in Spanish. Later, with more offers than we could handle and with a new sense of confidence that we might have something to say and that our Spanish might be passable, other people shared the work.

At the UNAM we spoke before groups as large as 200 to 300 people. UNAM has 125,000 students, is public, and generally the students there are on scholarships. It is divided into strict divisions, such as engineering, physics, etc.

Most of the different divisions had a Struggle Committee (Comite de Lucha), a radical organization of students. The different committees, although they shared the same name even at different universities, were autonomous from one another and, while some groups worked with others, in some cases we could not combine meetings with different groups because of political differences between them. Some struggle committees have more support within their specific schools; some are aligned with specific political parties outside the university. They work at a variety of levels inside and outside the university. Our talks were generally sponsored by these committees.

We generally spoke about who we were, and what we were doing. We were asked how we intended to develop a people’s science, what projects we had toward this end, and what we were doing to expose and combat imperialism and imperialist science.

At a meeting with students from biology, math, and physics, we were asked to talk about how people from different fields could work on projects together. in response, we gave the example of industrial health projects where people with training in chemistry, medicine, physics,engineering and biology can work together with workers who have detailed knowledge of the production process. To illustrate that expertise was not required to work on scientific problems we cited the examples of our research into military weather modification done by the Chicago group where no one had any prior knowledge of meteorology, and the Madison Science for Vietnam project which evaluated new drugs used in the treatment of TB where most people working on the project had no knowledge of medicine.

During another meeting, before some psychology students, we were asked how psychology could be used for the people. We mentioned, as one example, how some of the literature of the women’s movement, like Our Bodies, Our Selves, had helped break down the physiological and psychological myths of women’s inferiority. The mention of this book evoked a great deal of interest.

In addition to speaking at the UNAM, we also spoke to different groups at the Politechnic Institute, a large school devoted mostly to applied sciences.

In addition to the universities, we had an opportunity to speak with some high school students. At a high school, one speaker discovered that half of what he was going to say had already been written on the walls of the school. And while he didn’t find the class that had invited him, another class commandeered him to speak. Our talks to workers’ groups unfortunately fell through. However, at almost any radical student headquarters at UNAM we had the opportunity to see and talk to students and workers. There was one joint student-worker demonstration at the UNAM while we were there.

Our own participation was only a part of what students were doing themselves on the subject of science for the people. At the chemistry school we showed the film Struggle for Life4 as the first part of a series of ongoing programs. Other topics included: The Role of the Scientist in Society, Teaching in the Critical University, Self-Education, Methods of Science Teaching, Science and Social Structure, and a Round Table. The talks spanned a two-week period.

The radical students we met were very well versed in political theory. (Small bookstalls around UNAM sell copies of Marx, Lenin, the Peking Review and the latest from the Moscow press.) They have a clear idea of the class struggle and support the struggles of workers. They understand the nature of imperialism and imperialist science.

The radical students we met were very well versed in political theory. (Small bookstalls around UNAM sell copies of Marx, Lenin, the Peking Review and the latest from the Moscow press.) They have a clear idea of the class struggle and support the struggles of workers. They understand the nature of imperialism and imperialist science.

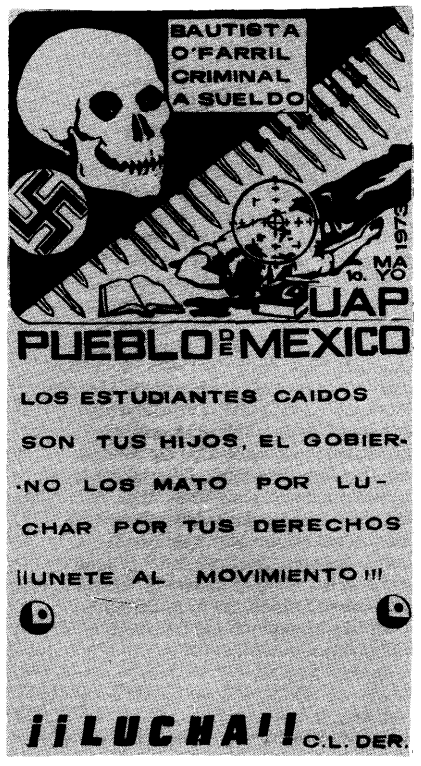

Their political situation differs from ours in a number of respects. The students have to deal with repression on a day-to-day basis. (A few weeks ago fourteen students were arrested as they prepared to attend a demonstration in Puebla in support of a worker’s struggle. There are hundreds of political prisoners in jail; many people have been killed for their political activities.)

The radical students feel the importance of having a revolutionary party which has a clear direction. Other issues are secondary, except as they support the party, as we found out trying to discuss women’s liberation. They view the revolution as international and are interested in the struggles of the Third World people in the U.S. They asked for more information about blacks, chichicanos, and Puerto Ricans. They also asked for information on U.S. corporate and scientific involvement in Mexico. Also, the struggle committees are in touch with revolutionary movements around the world.

Even among those Mexican students who were not politically active, almost all that we met understood U.S. imperialism. They also had a very clear analysis of the class structure in Mexico, something perhaps unusual only from the U.S. perspective.

Our contact with the politicized students of Mexico left us with the feeling that we are kindergarten Marxists at best. In contrast, they had not explored their sciences and the possibilities for study and struggle within the sciences themselves, nor had they analyzed the role of professionalism. The learning was mutual. In Mexico City today we fancy that there is Ciencia para el Pueblo (Science for the People) thinking going on. But what about ourselves? Are we ready to study and better educate ourselves for ideological struggle? There is an immense literature that we must explore. And the Mexico meeting left us with a sense of the urgency of that exploration.

We observed another difference between the Mexican academic left scene and our own. There is a great gap—nearly a chasm—between the politicized professor and the politicized students. They go their separate ways and interact minimally. In the current struggle for university self-government by students, staff, and faculty they work together but more as allied blocs rather than as an integrated movement.

Also, we met some passive and some “friendly” active resistance to an attempt by two of our women to meet with a group of women students (“Why only women?”). Unfortunately, this was late in our stay, so we didn’t have the time we needed to talk through the impediments and explore the questions we had about the life and oppression of women on all levels of Mexican society.

The patterns of repression in Mexico are different from our own and therefore confusing. In an atmosphere that seemed permissive in the extreme to us, with Marxist ideology talked about and taught openly, where walls were plastered with radical slogans and wall newspapers, where anti-imperialist analysis seemed the stuff of everyday life, there were also the arbitrary powers of detention, the wanton attacks on public meetings from the servants of a government self-labeled as the living continuation of the Mexican Revolution.

Nearly Banished

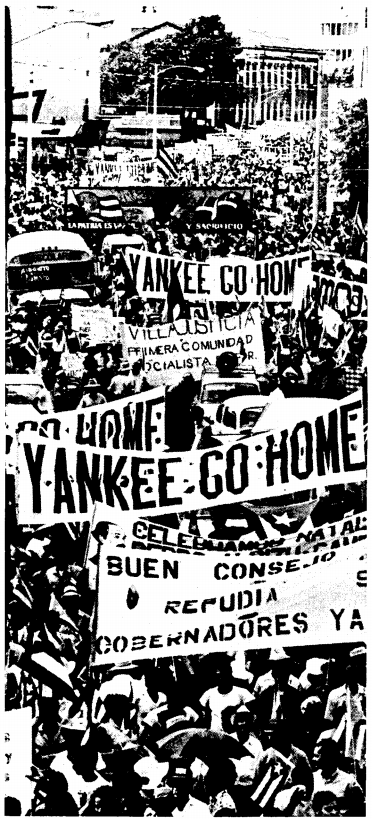

We, ourselves, became victims of this repression. Five of us and one Mexican student were arrested when we attempted to hand out a declaration entitled “Toward an Anti-Imperialist Science” [see pg. 18]. The production of this declaration brought many of us our first culture shock as we discovered that it was possible to write a joint leaflet with 8 people, then have it debated by 40 people, and to do all this smoothly and without any pain. The second came when we discovered that 20,000 copies of the leaflet were going to be produced, and that for only one campus. The leaflet was written jointly by Mexican students and people from the US., and was signed by 23 different university and high school student groups, a university workers’ group, and SftP.

We distributed the leaflet together, both Mexicans and North Americans, at the conference building on the 28th of July. After distributing it for fifteen minutes, some men, assumed to be either employees of the CONACYT or of the Meeting Hall stopped us from distributing the leaflet inside the buildings. This sent some of us outside the hall while a few wiser, more intrepid souls went further inside the building. (It was a mistake to go outside. We should have demanded ID’s from the men and insisted on our right to distribute literature as guaranteed by the CONACYT officials.)

Outside leafletting went on peacefully, if a little moistly, in the soft rain until, a distance away from the door, we saw burley plain-clothesmen hustling off one of the Science for the People women and a Mexican student. Four of us converged on this group, the men tried to shoo us away, they were “only going to ask a few questions, nothing more.” Six of us, five North Americans and the one Mexican, ended up in the nearby office of the Ministerio de Gubemacion, which is equivalent to the F.B.I. Aside from asking our names and nationalities, they did nothing more than walk in and out of their office looking busy and important. After two hours we were taken to what we thought was dinner. Outside, our friends and newspaper reporters had been mobilized, and they demanded and received our true destination: the office of immigration.

We were brought in through the back door, and put in a small room with two North Americans and one Colombian awaiting deportation. There we sat down to wait. The Mexican student was taken away, questioned, photographed, and released (he had only a tenuous connection with our leafletting). Although we were all asked to write our names innumerable times, only two of us were questioned. One of us was harassed and insulted by the big “Chief’, was designated our leader, and isolated from the rest of us. From this vantage point our comrade could see friends and reporters out the front door whenever it opened, and out the window in the other direction.

| PRESS RELATIONS

Concerning the press, our relations were, as usual, a mixed lot. Preparations had been made We also appeared on educational T.V. A journalist from Excelsior who also runs a panel show Our overall strategy with the press was that we welcomed coverage, but that our task was reaching the Mexican students through other means. We also resisted the press assumption that stories must be organized around “human interest”, and that this meant details about supposed leaders. We explained many times why we declined to give personal information: because some people were more vulnerable than others to reprisals, and more importantly because of our view of collective work and rejection of media-made leaders. We were aware, |

The long hours during which we calmly awaited the possibility of deportation were harried and busy for others. The high drama was taking place elsewhere. As we reconstruct it, the relative merits of deportation or release were being debated among the CONACYT, the AAAS, the political police, the U.S. embassy, and at least the perifery of the Mexican cabinet. The authorities decided that it was less trouble to release us than to deport us. The Mexican government had spent a quarter of a million dollars on its image and didn’t mean to tarnish it. The result was plain from the benevolent guise of the formerly blustering chief. We could go if we refrained from distributing literature outside the Meeting. We were let out the back door and we spread out to locate our faithful friends in and around the building.

We discovered the next day by reading Excelsior, a Mexican daily newspaper, that our release was retroactive: Mendoza, the information director of the office of immigration, “denied categorically that a group of North Americans who formed Science for the People were detained or presented before the Immigration Authorities.” (Shades of Ron Ziegler.) Not even Science, the AAAS magazine, took this seriously. In the condescending and studiedly non-political accounting of our activities in Mexico, they described our arrests.5 The day after our arrests people stopped by the literature table to find out about the incident. The students shook our hands in solidarity and looked on knowingly, perhaps not believing that we had gotten off so easily.

Extravaganza with Light and Sound

In general, the international meeting “Science and Man in the Americas” turned out to be more or less as we expected: not a serious scientific event, but rather a public relations extravaganza with light and sound. Our own observations were confirmed also by the many reports brought to us by friendly people who would come to our table fresh from the frustration or boredom of the symposia and eager to sound off.

In general, the international meeting “Science and Man in the Americas” turned out to be more or less as we expected: not a serious scientific event, but rather a public relations extravaganza with light and sound. Our own observations were confirmed also by the many reports brought to us by friendly people who would come to our table fresh from the frustration or boredom of the symposia and eager to sound off.

- The composition of the Meeting: There was a striking absence of working scientists and a preponderance of administrators, directors of institutes, heads of programs, and politicians of science on the one hand, and of students on the other. But active researchers and teachers both from Mexico and from the rest of Latin America were conspicuously absent.

- Both the quality of the presentations and the degree of control by the organizers of the Meeting varied greatly from session to session. But we could distinguish 4 kinds of topics:

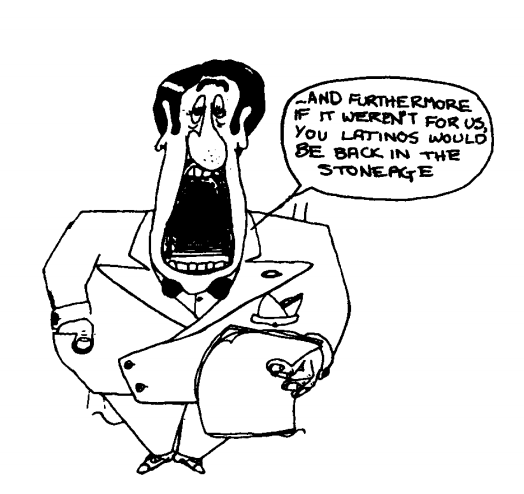

- The themes which were central to the objectives of the organizers were those which dealt with technology transfer, organization of resource exploitation, social control, and population control. Here the quality was miserable. With few exceptions we were offered neither new information nor any new insights. Rather, we visualize the speakers grabbing any old paper from a desk drawer before catching the plane. The content was limited to reaffirming the basic myth of the Conference: the science and technology of different countries differ only in the degree of development; therefore, “backward” countries aspire to follow the steps of “advanced” countries, and these only wish to help them; that once modern technology enters in search of profit, some hidden hand, a la Adam Smith, takes care of social questions.In these symposia the control was most rigid. The session organized by Rudolpho Stavenhagen was cancelled when it was realized there would be radical content in his session. As noted earlier, Jim Cockcroft was first demoted from speaker to commentator, and then the chairman cut off his microphone when he commented; all the suggestions and volunteer participants from a group of women who had been preparing for the session on family planning were turned down; questions to speakers had to be submitted in writing, and these were censored.

- Technical topics related to resource exploitation and control technique. Here some of the papers were quite competent in the narrow technical sense, some chillingly competent in their indifference to human consequences. For instance, one paper discussed behavior control, and made passing reference to the use of lithium on prison inmates as a hint of areas of application. Other papers were illustrated self-praise by such institutions as Scripps, U.S. Hurricane Research Center, and Rockwell International, resplendent with color slides and movies.

- Decorative themes, such as symmetry, archeoastronomy, and mathematical biology, that had nothing to do with the basic aims of the Meeting, but which succeeded in recruiting some distinguished scientists. Here irrelevance guaranteed freedom of discussion.

- Themes of decidedly secondary importance to meeting officials, such as Tropical Ecosystems or The Woman in Science (a topic which was added to the program at the last minute). Here the Meeting organizers authorized the symposium, selected the coordinators, and exercised little or no further control. These sessions allowed an open microphone and broader discussion.

- We observed a systematic difference between the U.S. and Mexican presentations of the general topics. The Americans emphasized narrowly technical considerations and showed a naive faith in the enterprise called free, while even those Mexicans who accepted the official line showed greater concern for the broader picture.

The central organizing principle of the Meeting was the contradiction between the needs for tight control of the ideological content and for credibility, which undermined that control and created space for dissenters. Among the least controlled of the sessions of the Meeting was the symposium on tropical ecosystems. When a vacancy appeared at the last minute, Science for the People was invited to present a paper and participate in a general round table discussion in order to have a critical viewpoint heard. The invitation was extended to the group, not to any individual member, on the afternoon of our arrest.

Our paper for the symposium on tropical ecosystems was organized around the interactions of military, corporate, academic, civil service, and guerrilla science in the tropics. It was shown that the military and corporate science rips off the tropical environment for anti-human purposes, that those who study the tropics in order to exploit it and those who study to defend it are not colleagues but enemies. Also, the military and corporate research are bad science, narrowly empiricist, anti-theoretical, and over-specialized, with an exaggerated faith in equipment and scorn for thought. Insofar as they dominate research they serve as a model for science which leads to its internal debasement as well. Our paper contrasted this kind of science with the richer and more progressive guerrilla science [see description in box on page 14 called Guerrilla Science] .

At the round table we had the support of several other North American and Mexican participants in challenging the current patterns of education, research, and exploitation of tropical resources. An interesting pattern developed in which we served to express directly and bluntly what some of the others had hinted at obliquely; our points were picked up and quoted by other panelists; or they opened up a topic and then we followed through. For instance, one biologist expressed dismay that Latin American scientists often read in the U.S. journals about work the yanquis had done in their own countries without their knowledge. We took this up to demand that a complete set of all specimens collected by foreign expeditions be deposited in the national museum of the country where the work was done; that only duplicates may be removed; that a research report appear in a journal of that country and be presented verbally in a seminar at the national university; and that field expeditions require a special research visa rather than be allowed to enter as tourists. There was an enthusiastic response.

Evaluation

In order to evaluate our activities at the conference, it is necessary to understand that this conference was quite different from any that SftP had participated in previously. It was very different in terms of the composition of the attendants (notably in the absence of working scientists), the scientific content (almost none), and the local political environment. Also, it was an important imperialist event.

When the meetings were first announced we saw as our primary objective the development of anti-imperialist international solidarity around questions of science and technology. The work of expose, literature distribution, and counter-conferences was all subordinate to this goal, which would necessarily take us outside of the Meeting. Yet, we had only vague notions of the political environment in which we would be working and only a few prior contacts. Therefore, we spent a lot of time and effort, beginning months before the meeting, to develop contacts with radicals in Mexico. These contacts were extremely important to us. They provided a friendly environment in what otherwise would have been a very alienating situation; they provided material support, typewriters, mimeograph, etc.; they arranged opportunities for talks and discussions, and bolstered our political strength far beyond the small numbers of the SftP group.

But in some ways we failed to develop these contacts sufficiently. Often we did not succeed in involving Mexican friends directly in our activities. Some exceptions were the writing of the denunciation of the conference and the preparation for the T.V. program. There were a number of reasons for our failure to work more directly with other people: first, the Mexican movement had many other activities and priorities; second, there was the problem of the language; and third, the very repressive nature of the Mexican government meant that public planning meetings would not have succeeded.

The Mexican movement saw the AAAS meeting as one of many instances of imperialist intervention, but not as an event that itself required a major organizing effort. In the context of a very active movement, deeply engaged in local struggles, this view of the meeting was quite correct. The Mexican student movement was already working closely with peasant, worker, and communtiy groups, providing medical, legal, and technical aid. Although they didn’t call their work “science for the people”, they were already doing it within a developing revolutionary struggle. Understandably, our pre-conference efforts to pull together a local support group met with a lot of frustration; people just had too many other ondas [trips]. At the very beginning of the conference, a group finally met to plan activities. The group decided to write a general denunciation of the conference rather than attempt criticisms or activities around specific sessions.

Our own activities as well did not center around the specific content of the AAAS conference, but rather around talks and discussions of science for the people. In many of the counter-discussions we found ourselves in the role of “experts” giving our line on science for the people. We continually attempted to break out of this role by being as informal as possible, by encouraging open discussion rather than simply questions and answers, and by asking people present to help out with translations. These efforts, however, were only partly successful; it seemed that often we were presenting our ideas and answering questions but other people were not presenting their own ideas and examples for discussion. This problem could have been handled better if we had worked more closely with the Mexicans in planning the counter-sessions and had structured the sessions so that both Mexicans and North Americans were giving the introductory raps. The general interest and enthusiasm for the counter-sessions suggests that there would have been people willing to participate more directly.6

One serious difficulty in working closely with the Mexican movement was that the majority of o1u group did not speak Spanish sufficiently well, in spite of the fact that four of us had spent three or four weeks each studying in Mexico to improve our Spanish. This problem could have been overcome had we made a deliberate effort to seek the assistance of bilingual people. This would have made it possible to work more closely with Spanish-speakers and would have allowed fuller participation of those of us who spoke little or no Spanish. The differences in language ability in our group contributed also to a more extreme division of labor than was necessary or healthy. One person did too much public speaking, one was continually making contacts and organizing, another typing and running off leaflets, some spent long and alienating hours at the literature table, while others generally had difficulty participating. Also, the member of the group who was most fluent in Spanish, because he did more speaking and oral translating than anyone else, was immediately defined as the “leader” in the eyes of many people.

We learned only late in the conference that problems stemming from language difficulties could be overcome with the help of people outside our group who could translate. Toward the end of the conference, more people in the group were speaking publicly, which gave us a more collective presence and helped more people in the group to develop and present their ideas. We observed an important phenomenon—that those of us who had to speak and answer questions were forced to develop our theoretical conception of science for the people in more specific and concrete forms.

As a group, SftP functioned very well. We had broad general agreement oil most issues. There were very few disagreements and hassles, and decisions were made easily. The cohesiveness of the group probably stemmed from the fact that all of us had worked in SftP and everyone had known at least a few other members of the group before the meeting. But of course, there is a real contradiction between working as a cohesive political group and opening the group to allow new people to enter, participate, and grow.

Besides our general self-criticisms, there are a number of specific ways we could have functioned better. For example, we did not know enough about Mexican politics (we should have asked the students to give us a political orientation on Mexico). We were not adequately prepared to deal with the question of women’s liberation in the Mexican context, and the attempted women’s meeting was planned for too late. We should have prepared more leaflets and generally had a higher profile at the conference. Also, our planning meetings were held late at night when people were tired, with the result that plans were made for the next day, but little more. After a few days at the conference, we knew there were times during the day when there were lulls in activity. Those times could have been used for more thorough discussions and evaluations. Our self-criticisms, however, should not be read to imply that we think our efforts were unsuccessful; on the contrary, we believe it was one of the most successful SESPA actions and certainly the most thoroughly prepared in advance. The criticisms were presented so that we can collectively learn from them and do better in the future.

We feel very positive about our activity in Mexico City. The experience convinced us that there is a ripeness for international cooperation in developing an anti-imperialist movement in science, a movement which recognizes the inherently political nature of science, not only in its use, but also in its internal organization and content. We found that we and our Mexican comrades were in complete accord, that as the class struggle is developing as a whole, a guerrilla struggle must be waged in science. That struggle is now being born.

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 5 <<

Notes

- The Jason Committee is the group of elite scientists that advises the Pentagon on advanced war strategy. See Science Against the People, Berkeley SESPA, 1972.

- Remember that this official had been at the Washington, D.C. AAAS Meeting, where we fought for our right to a literature table, and further, that CONACYT had read Por Que and had it translated for their own use last December.

- Our Bodies, Our Selves, Boston Women’s Health Collective. A book about women by women.

- film about struggle of Vietnamese medical workers in the Indochina War zones.

- Almost 1/3 of Science’s meeting report was about what SftP did not do at the meeting!

- One of the criticisms leveled at us by Mexican students was that they thought we came here just to learn what we could learn, and they didn’t really see how we could keep up contact. We weren’t sure ourselves how to do this other than through sending literature and letters. We didn’t expect to become comrades in two short weeks. Comradeship, we were reminded, would come out of time by testing out each other’s willingness to help, etc.