This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

AAAS Critiques

by Gar Allen, Bob Yaes, Frank Rosenthal, Howard J. Ehrlich, & Northside Chicago Science for the People

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 2, March 1973, p. 20 – 26

ST. LOUIS

Below is my accounting on only a couple of points.

I am assuming that we think SESPA activities at large meetings such as the AAAS, ACS, APS, NSTA, etc., are valuable and that we should continue to make our presence felt. For me, involvement with SESPA at the AAAS meetings (I haven’t been to others) has come to serve two purposes: (1) It gives me a chance to exchange ideas and experiences with other SESPA people—i.e., to learn a lot and to make or renew friendships; (2) It also provides a chance to raise issues in the “established ” science context that must be faced by all scientific workers if we are to ever make science a beneficial force. The problem is that it is difficult to do both of these things in the course of four short, action-packed days and nights. In the past, we have used those four days both to build a temporary organization that could carry out certain actions, and to plan and carry out the battle simultaneously. I have come to feel that some more effective organization, to direct the SESPA actions at the AAAS meeting, should be built prior to the start of the actual convention. This past year something along this line was tried, with a planning session Thanksgiving weekend. But the group assembled in Washington proceeded as if such a planning session had never existed. I’m not sure what the reasons for this were, but I feel we lost a lot of valuable time, and may, as a result, have been less effective than we might have.

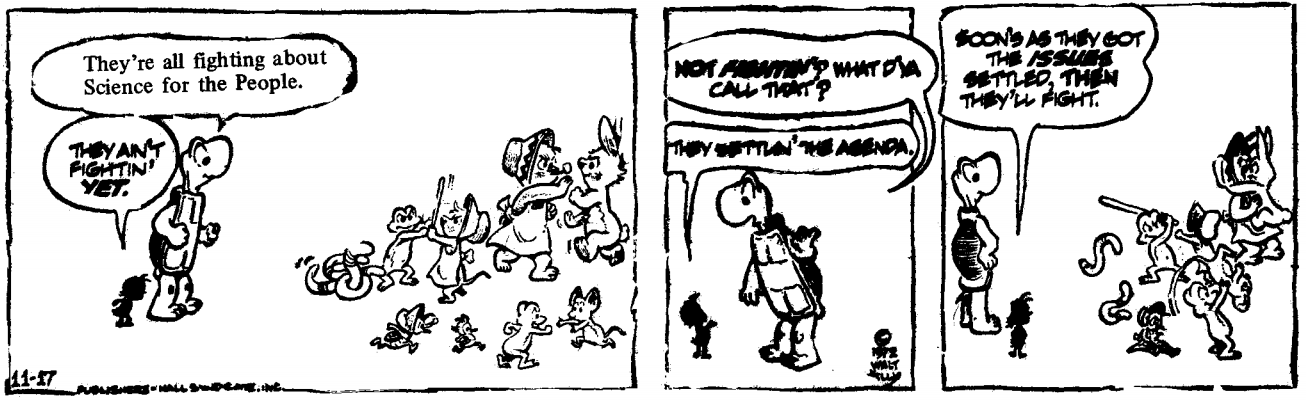

I am not enamoured of tight, highly centralized organizations. But it is obvious that we could have used something tighter at the recent meetings. Since we did not know each other, and had never worked together before, and since we tried to proceed ultra-democratically, we rarely got through with our doctrinal discussions and disputed until midnight. That is really too late to start planning in any serious way, detailed actions for the next day (such as what sessions to attend, what issues to raise in those sessions, etc.). We could have attended more sessions, raised better points, and engaged more rank-and-file AAAS members to attend our evening SESPA meetings if we had had more semblance of organization and direction. Few outsiders (outside of SESPA), and in fact few loyal SESPA members, wanted to sit through three and four hour meetings. Thus, I’d suggest something like the following: A planning session, open to all who want to come should be held Thanksgiving weekend, or some other time prior to the AAAS convention (with a new AAAS convention time appropriate advance dates will have to be selected). That group will constitute a central planning committee for the AAAS meetings. The planning committee will have responsibility for (a) making advance plans, including earmarking sessions that definitely ought to be attended, thus giving people time to do some homework and prepare themselves, and setting some general policies; and (b) running the actual activities at the AAAS meeting. The latter would involve someone from the committee chairing each evening meeting and presenting an agenda, as well as directing daily activities outside the evening planning meetings (including making sure the literature table was staffed, etc.). The Central planning committee could have other members added to it from among those attending the AAAS meeting, if that seemed desirable. Those SESPA members or others who wanted to work with SESPA could have input into decisions at the evening meetings, but overall policy issues should form a less central part of the discussions held during the AAAS. Those evening meetings should deal first and foremost with organizing activities for ensuing days and discussing situations which come up at the spur of the moment (such as whether to support a rally, etc.) The major policy would have been drawn up at the prior planning sessions and should not be argued out every night. All this requires that individual SESPA members (and others who join us) accept a little bit of discipline—but I think we can communicate our ideas more effectively, and make our presence more generally felt if we have first organized ourselves a little bit. I’m afraid we might have turned off some potential SESPA workers by our endless and meandering meetings.

Of the actual tactics we tried, two seemed to me particularly successful. One was attendance at various sessions where SESPA people raised issues which otherwise might not have been raised from the audience. I heard some good reports about general audience reaction to this tactic. The other was preparing short leaflets, distributed before a particular session, giving some facts about the person or persons speaking, or about the topic to be discussed. Both of these activities are good examples of what I think our main function at such meetings to be: education to a new point of view. As long as we choose the arena of a scientific meeting, that is the most positive thing we can do. There are lots of ways to educate, and sometimes restructuring a meeting, or actually disrupting it, can serve that purpose as well or better than the more “restrained and academic” approach. But we should never forget that once we begin turning off the average AAAS member in the audience, we have started to defeat our purpose in being there. Thus, I think our restraint, our willingness to be non-arrogant, at the past meetings helped win us more general support. It became clear, however, to many of us who attended one or another session to raise points and provoke discussion, that we should have been better prepared. The average AAAS member at those meetings will respond much more favorably to facts than to simply generalized viewpoints, or especially rhetoric. Again, the need to plan ahead is especially important for us to serve our most effective educational role.

Hope this gives some food for thought.

In peace and struggle,

Gar Allen

St. Louis SftP

NEWFOUNDLAND

SESPA people don’t seem to be very into organizing scientists around their own oppression. It should be obvious that people are more dedicated to the struggle if they are fighting for themselves rather than doing somebody else a favor, out of compassion for those “porr blacks” or “poor Vietnamese”. This means dealing with such question as working conditions and job security for scientists, which might seem like a wishy-washy liberal issue, but which, nevertheless, is an immediate concern to many of the scientific workers present at the meeting. It also means pointing out the power relations that exist in science, namely that there is a small closed clique of self-annointed elite who themselves do no scientific work (research) but nevertheless seem to be in complete control of the institutions of science (the AAAS, APS, NAS, High Energy Advisory Committee to the AEC, etc.) These people are not only the ones primarily responsible for screwing their colleagues by throwing them out of work, but also have the closest ties to the government and are most willing to cooperate with the DoD, AEC, CIA, etc.

— Bob Yaes

CORNELL

SESPA has conscientiously avoided both organization and program in its structure. This is fine if its aim is to be merely a clearing house and information center for “radical” science activities. As such it does not even have the political structure of a united front organization. It cannot endorse national programs like “Sign the October 26 Agreements Now!” or even “Stop Jason!” It cannot join coalitions. It cannot call a press conference. Etc. A clearinghouse is a movement resource but not a political force. Many SESPA members want SESPA to be more than a clearinghouse and this results in certain contradictions. Even the idea of going to a AAAS convention for “radical agitation” and “organizing” contradicts the idea of a clearinghouse. A clearinghouse (usually) doesn’t get arrested handing out literature. Neither does it organize meetings for “radical actions” or call demonstrations. When it does so, it is not really acting as a clearinghouse.

To some extent there is a “hidden program” in SESPA as far as U. S. imperialism, racism, and the role of the scientific establishment are concerned but it is so well hidden that even the “hard core” SESPA members who originated it don’t know where it begins and ends. In the weeks before the AAAS convention in Washington, there was little discussion, let alone collective agreement, as to the purpose and objectives of SESPA’s attendance at the AAAS convention. At the SESPA meetings during the convention objections or endorsements of specific tactics came from a dozen different (and sometimes contradictory) reasons rather than out of a political context. An example is the meeting where we decided whether or not to enter a AAAS presidential address and read a brief statement. The action could have had tremendous significance. But the discussion, postponed to a few hours before the address, contained a jumble of tactical and political considerations, and with clarity of purpose lacking, the action was sensibly abandoned.

At the AAAS convention, SESPA was forced to operate as a committee of the whole at all times, made up of whoever happened to be there at the time, making decisions for no more than a day (sometimes a few hours) at a time. When eight people got arrested the organization was incapable of responding. SESPA’s militancy was dangerously ahead of its organizational and defensive capabilities. One must also look critically at the politics of mobilizing others to militancy in such a situation.

Eliminating all structure was the only way we could assure ourselves that a genuinely democratic process was at work. In fact, it resulted in a most undemocratic process. It ts not democratic to make decisions on the basis of who is left after a four hour meeting. Or to make the decisions that satisfy all objections (i.e. the lowest common denominator). In times of crisis or when quick decisions are needed, some decisions are in fact made. (For example the decision to not have our own press conference after’ the arrests but to join with the Fieffer-Westing press conference.) These decisions are made by individuals who are most closely identified with the organization by outsiders or who are most closely in touch with information, finances, etc. Such decisions and individuals are never held accountable to the “membership” and in fact most people don’t have much idea where they come from. The situation is not excused or ameliorated by the fact that decisions are never made until absolutely necessary (i.e. a crisis). All this means is that planning is impossible. The tolerance of structurelessness is repressive. It prevents unity and collective feelings of a group from being struggled out and expressed. It further precludes channels of responsibility, individual and collective. An example is the lack of clear responsibility for deleting a paper written by the Chicago chapter from the SESPA booklet for the AAAS convention.

SESPA’s organization is very confusing to outsiders. This combined with general ineptness (e.g. putting May, 1973 on December’s issue) and the “counter-culture” image of SESPA were at least as responsible (probably more) for turning people off at the AAAS convention than the fact that our politics was “too radical.”

These are more than tactical considerations. People’s hesitancy to join SESPA is in some sense rational. Some are reluctant to join forces with a group that does not have explicit politics and organization and in some cases does not take itself seriously. Of course people who see themselves as “activists” may join in the hope of changing things. But if SESPA is to be more than a clearing-house it must be a political organization. It can’t be an activist club in between.

Uncertainties of program and organization led to two important kinds of problems during the AAAS convention that were also somewhat evident before the convention and now too: communications to the public (press, etc.) and relations with other organizations. Press relations, for example, were handled by people with little previous SESPA experience. Relations with other organizations were basically not handled at all. Because of this our relations with Medical Aid to Indochina and to the Wald-Feiffer-Westing group were at best confused. Even our internal communications (such as with our New York and Chicago chapters) were very strained. Also many contacts with other groups were not made which could have been.

Our “purism,” especially in the absence of a clear political program, tended to isolate us at the AAAS convention. It was wrong and elitist not to respond directly to the arrests of our members at the AAAS conference. In some ways the actions of the AAAS, decided at the level of the Board of Directors sharpened some of the very contradictions we had come to expose. Only a week before the chairman of that board had written an editorial in Science magazine committing the AAAS to the “free exchange of ideas.” Many who knew about the arrests were interested and sympathetic. Many more left the conference never knowing that it had happened. We took a purist outlook, thinking that it would dilute our politics if we talked about repression. In the same way we refused to deal with the AAAS, thinking that it would pollute us if we made demands upon it. Don’t we make demands upon the U. S. government! At times we also took a purist attitude toward the press, shying away from setting up some kind of consistent relations or contact with them. These attitudes did nothing to make our politics more radical or progressive. They only served to isolate us.

Frank Rosenthal

Milton Team

MADISON

Considering the geographical separations we all suffer from, the preparation for the meetings was well done. We received information in Madison good and early and were sorry that none of us could attend the Thanksgiving planning session, the results of which were sent to us by mail. The booklets made especially for the conference hit their mark; for example, the “AAAS in Mexico” pamphlet had conference editor Walter Berl shaking in his shoes and urging us to show restraint. I hope SESPA members who haven’t taken part in these preparations, and in the convention itself, will make the sacrifice next time. It is the only sort of action which we take as a national group, and the experience helps to unify us all as well as showing us who and where our friends are.

At the conference we faced decisions which we were not quite ready to make with political certainty: how to restructure the sessions and why; whether to put resolutions before the AAAS board; how to work with Pfeiffer, Westing & Co., and so on. In discussions with AAAS members we could not always bring home the connection between the subject matter of our booklets and the political role of the AAAS as an institution. The “interlocking dictatorships” approach and its derivative of “guilt by association” are good analytical methods, but can be too general for tactical use in the enemy’s back yard. For our own sake we might discuss among ourselves the specific political differences between SESPA and the various professional societies. After all, SESPA was founded four years ago on the realization that the American Physical Society, a microcosm of the AAAS, was an improper institution to work through. Getting this issue straight can help guide our oppositional efforts in the future, and help educate those, such as the press, who still don’t understand why we refuse to become part of the standard AAAS format.

The question of political control remained unclear. If our goal was complete control over a few sessions, then of course we now have much reason for self-reproach. But the duel over ultimate control was a myth from the start behind each session chairperson were the hotel security guards, Scribner, and eventually the metropolitan police under AAAS direction. Any control we might have seized would have been under some degree of AAAS benevolence and restraint. The political control problem should be faced by all SESPA groups in their home cities, where they have the time and numbers to challenge oppressive institutions fundamentally. At the AAAS conference about 50 of us came together briefly and with relatively little acquaintance to oppose a large, well-organized association. In such a situation we must use the powers we actually have-to convey our politics, to expose the political realities behind the conference, and to win supporters over to our struggle. If we can protect our right to do this without joining up with the AAAS management, that is a political victory. We succeed each time we restructure a session well enough to get our point across to those attending. The AAAS management is afraid of our ideas, and they will provide the confrontations by their repressive acts. In Washington we were physically brutalized by the city police and constantly harassed for merely handing out leaflets. AAAS press officials like Thelma Heatwole purposely tried to shut us off from the press, and five boxes of our literature were “mysteriously” stolen. Such facts should be placed before all the people as evidence of real political oppression. At national events like the AAAS conference our power lies in our ideas and in our spirit, not just in our numbers or brute strength.

At best the establishment U.S. press sees us as sensational news; in Washington they ignored the political issues we represented, waited around for a police bust, and then portrayed us as violent disruptors. Ultimately we must rely on our ability to reach others through discussion and circulation of our literature. But a more consistent press policy will help nonetheless. In addition to one well prepared press conference we should have two or three people in charge of press contacts throughout any convention. They could arrange informal, in-depth interviews and be ready to respond to emergency situations like the bust. This might have saved us from the embarrassment of having issued two different press releases simultaneously and still having failed to meet press deadlines with our side of the arrest story.

Our “anti-leadership” organizational difficulties are great—we risk all the dangers described by Joreen in “The Tyranny of Structurelessness”. In Washington we were smart to plan more discussion on this matter, and I hope an “organizational” conference will take place in some form.

Above all, I hope we keep the spirit of cooperation and patience which brought us through that week of pressure and little sleep.

for Madison SESPA,

Doug Hanson

BALTIMORE

Great Atlantic Radio Conspiracy

Some people were clearly dissatisfied with the activities of Science for the People at the 1972 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. At one of the radical caucuses, it was decided that we should submit the grounds for our dissatisfaction for distribution to the membership.

To provide an effective radical presence at the meetings of scientific and professional societies, I think that the following conditions will have to be met. They were generally absent from the AAAS meetings.

- There should be a central, public, easily accessible room where radical scientists can regularly meet.

- At formal meetings, radicals should not be embarrassed at having meetings that start and end at a designated time. Further, it is not elitist to withhold the right to participate from passersby or the curious who just wandered into the meeting room. Nor is it elitist (at an annual national meeting) to insist that chairpersons be capable, and speakers be relevant and concise (Local chapters and organizations should be the place for training.)

- There should be some formal meetings where people from different cities could exchange information on what they are doing—their current programs, ideas, problems, actions, doubts, etc.

- There should be workshops for radical scientists and for outreach to liberal or alienated professionals.

- There should be some registration procedure for radicals in attendance as well as some systematic efforts at collecting the names and addresses of the interested or the curious. Without this, there can be no formal follow-up.

- Some persons should serve as press officers; a simple press packet should be prepared; and when unusual events are planned, or occur, press contact should be arranged to help reporters understand what took place.

- Persons attending regular sessions in order to provide a radical critique must do their homework. A tightly-reasoned, well-written, coherent paper presented by an articulate and poised speaker is not going to shatter simply because a group of radical antagonists give spontaneous expression to their outrage. While to those of us who share a radical conciousness, the anti-human implications of a given paper may be obvious, most persons in the audience will either be unaware of those implications or they will share the values of the speaker. I think the purpose of a radical presence is to make those implications explicit, to present a critique, and perhaps an alternative. I think that this takes considerable preparation.

- Formal attempts at evaluating the outcome of a radical presence at scientific meetings should be made. What did “straight” people think of it? How did radical participants evaluate their own effectiveness? Did anyone learn anything?

Now all of these conditions may require more people power, time, money, or other resources than are available at any given time. At the least, there should be a literature table and a large, central, easily accessible place to hang out.

Any assemblage of radicals these days can be quite confusing without a program. I had the impression that some meetings were dominated by persons who had very little investment in the development of a science for the people or for the organization, Science for the People. I think that this is potentially disasterous. I myself participated as a radical scientists, but not as a member of SftP.

As one of the organizers of the Union of Radical Sociologists, I think we failed in part because we could never decide how to organize ourselves at sociology conventions and, in part, because we had too many people involved who were uninterested in radical sociology and/or in building a permanent organization of radical sociologists.

As a sociologist, I think I can demonstrate that the constituency of the left is larger than ever before. At the same time we are organizationally weaker. Unless we develop viable organizational forms, we shall lose that constituency. I think that a national organization of radical scientists operating out of autonomous local groups will be difficult to maintain. But it needs to survive, because it is an important strategy for revolutionary organizing in this country.

Howard J. Ehrlich

Research Group One

2743 Maryland Ave.

Baltimore, Md. 21218

NORTHSIDE CHICAGO

We were disappointed in our failure, as a chapter, to carry through with the AAAS projects which we had planned before the conference began. This caused us to reevaluate the “collective” nature of our work. We decided that despite the apparent consensus of our planning sessions a lack of hard planning diffused the sense of individual responsibility, so that each of us did little while each expected the group to pull us together. This was our own problem, and we have since worked to overcome it by clearly spelling out individual responsibilities within our group projects. In particular, “the one who knows most” about a particular project will not be allowed to dominate the project, because this encourages passivity in the rest of us and makes projects become, de facto, the work of individuals rather than of the group.

Not being as cohesive a unit as we might have been, we were drawn into the excitement of the convention as individuals—and receiving no “institutional” support or encouragement for the activities we had planned from SESPA as a whole, we failed to accomplish any of the important positive goals which we and SESPA had set for ourselves at the Thanksgiving planning session.

SESPA’s role at AAAS was primarily reactive-directed towards trashing establishment science rather than developing real alternatives. We believe that AAAS and its superstars are straw-men. They are no more worth our energies than is Richard Nixon. Our primary audience consists of disaffected scientists who are unhappy with their options within the present system. Mostly they are not radical (but can become radicalized through alternate work options), but many are willing to relate to our analysis if we can give them support and activities they can participate in.

Our getting busted brought sympathy and interest. It was an opportune moment to reach people with our message, but we flubbed it, because it was more fun to do anti-people science than science for the people. We’ve got to start relating to people as working scientists rather than as kids, outsiders, hecklers. Let’s face it, 250 people at an anti-war demonstration at a moment of overwhelming antiwar sentiment shows that we’re not reaching the people we go to AAAS for.

We have lost faith in the integrity of the organization to abide by democratic rule. Functional anarchy pertains in matters of the deepest import. We supported one of our members to go to the planning session in Washington, and three of us made special efforts to be at the AAAS conference on Monday night. Yet the history of our paper on “Science for Survival” shows that the one who has the last hand on the mimeo machine has absolute control over politics and content, instead of mere editorial responsibilities; and the fate of the 9 or 10 workshops planned at these sessions shows that SESPA doesn’t take seriously its organizational commitment to support the activities which it plans.

Every meeting rediscussed the issues of previous meetings—no decision was ever final. Thus, the meetings were endless and largely pointless. They drew our energies away from the tasks of recruitment and of preparing critical analyses of sessions. No planning meeting included the setting up of groups to plan positive activities such as workshops or recruitment efforts (in contrast to the committees on press releases, the literature table, etc.).

To stimulate discussion of concrete suggestions for SESPA reorganization, the North-Side Chicago chapter would like to submit these proposals, tentative as they may be; we are fully aware that they contain many liabilities. Instead of seeking specific criticisms of these proposals, we would like to see people make better proposals for achieving some of the advantages of more evenly dispersed powers and duties.

A Proposal for SESPA Reorganization

I. Introduction

Here are some suggestions in outline form for a possible reorganization of SESPA that would have the following advantages:

(1) a fairer distribution and rotation of duties among the chapters;

(2) a fairer distribution and rotation of power and, in particular, access to the means of production among the chapters;

(3) a fairer sharing of the financial cost of maintaining the organization.

The overall structure would have three components:

(1) autonomous local chapters;

(2) membership at large;

(3) a national office with a paid staff to carry out administrative work (channeling correspondence, arranging production of Science for the People, and so on), but not policy decisions.

II. Chapters

A group wishing to be considered a local chapter must provide:

(1) a list of x SESPA members (x must be greater than, or equal to 3), including one willing to be the local chapter contact;

(2) a statement of the focus of the group; this would include some statement of projects and general orientation;

(3) some contribution from each chapter toward the costs of Science for the People production, administrative costs and so on. Specifically, this means that a clearer statement of costs should be circulated to the membership. Such a better understanding of and support for the costs of the organization would assure more continuity in funding and less dependence on the salaries and grants of individuals;

(4) promotion of the magazine in its area by distributing it at schools, libraries, local professional society meetings;

(5) ability to function as an editorial collective when its tum comes up;

(6) filing of at least one annual chapter report.

III. Members-at-large are defined as persons who are not able to affiliate with a chapter.

They pay a suggested $10/year (less for students, unemployed, underemployed, etc.), which also entitles them to a subscription to the magazine.

All members, whether members-at-large or members affiliated with a chapter, are eligible to be delegates at regional meetings, which can be called by a chapter by a notice in Science for the People. The regional meetings will deal with coordination, policy statements, election of delegates to national meetings, etc. National meetings might be called to plan for AAAS meetings, to decide on policies of support for or cooperation with another movement group, and so on. All meetings, at all levels, should be open to all members.

— Northside Chicago

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 2 <<