This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Controlling Aggressive Behavior (or Stopping War Research)

by A Group of Students and Faculty of SUNY at Stony Brook

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 1, January 1973, p. 21 – 23, 26 – 27

INTRODUCTION

This article was written by a group of students and faculty of SUNY at Stony Brook, where Department of Defense (DoD)-sponsored research has been a campus issue for at least three years. Although this case history and analysis grew out of a struggle in a university community, we believe that it is equally relevant to other work places where the DoD attempts to channel research toward antipeople goals through grants and contracts.

We have tried to sum up our experience and provide solid information and analysis of the most important what’s and why’s, arguments and counter-arguments. In addition to presenting crucial factual data, we have made an effort to place the issue of banning DoD research in an historical and political context. We believe that this broader perspective is essential to a proper understanding of what is at stake and why and how we must act. We intend this statement to be useful as an organizing tool to anyone concerned with the elimination of DoD research. We also hope that it will generate debate about what is involved in confronting the university’s support of the American military. Comments and criticisms are invited.

THE FIGHT AGAINST DEFENSE RESEARCH AT STONY BROOK

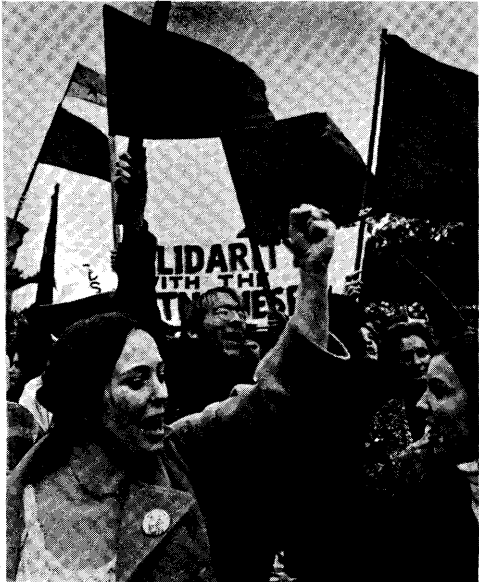

The war in Indochina has generated increasing awareness that the military depends upon universities to meet critical manpower and research requirements. At Stony Brook this understanding was first expressed in protests against military recruiters on campus. Demonstrations soon followed against personnel recruiting by industrial interests which were profiting from the war.

In March 1969, a demonstration against a Dow Chemical Corporation (napalm manufacturers) recruiter led to a demand for access to the university’s research files in an effort to expose suspected direct involvement of the university with the military. A group of over 100 demonstrators entered the graduate school offices where the records were housed. Acting under Stony Brook President Toll’s orders, the police attempted to evict the protestors. These attacks were repulsed and the files were successfully photographed and xeroxed.

As expected, the files revealed several active research grants funded by the military. Among these were grants directly related to such high-priority military projects as aerial reconnaiscence photography and chemical warfare. A few days after this information became available, 500 students sat in at the administration offices. One of their key demands was the termination of military-related research at Stony Brook. President Toll denied its existence, but in an effort to get the demonstrators to leave, he promised to open the research files.

He later allowed people to see only abstracts of the proposals, making it impossible to understand the actual applications of the research.

During the next two months it became known that the university was also applying for Project Themis funding. Project Themis was aimed at small but developing universities such as Stony Brook; it attempted to channel research into areas of immediate interest to the military. The Stony Brook Themis proposal included research on the technology used in missile guidance systems.

The movement directed all its efforts towards preventing Project Themis from becoming established on campus. This may have played some role in the Defense Department’s subsequent decision to turn down the university’s Themis proposal.

The limited victory over Project Themis temporarily forestalled the growing protest against all Defense Department research at Stony Brook. It was not renewed until the Spring of 1970, when the invasion of Cambodia and the killings at Jackson State, Kent State and Augusta led to a campus-wide strike. Once again an end to military research at Stony Brook was a key demand.

The faculty was finally moved to act. After a debate which extended over several days, the Faculty Senate voted to terminate DoD funding by a vote of 105 to 66. Toll, revealing once again whose interests he serves, sought to undermine the faculty vote.

In the Fall, the Graduate Council and President Toll engineered a reversal of the Spring vote. At a Senate meeting in which no debate took place, a mail ballot was called for, but the mailing contained no examination of the issues. Furthermore, at the meeting, Vice President Pond made it clear that the administration would not consider a faculty vote against DoD binding.

In the spring of 1972, students responded to the mining of North Vietnamese ports and the resumption of large-scale bombing attacks above the Demilitarized Zone. Again the computer center was attacked. Again police were called in. Again there was a student strike. And again the Faculty Senate voted to do away with DoD funding by more than two to one (75—31).

This time, students and faculty decided to press the demand that Toll abide by the will of the university community. In order to close off the argument that too few faculty had participated in the Senate vote for it to be representative, a petition was circulated demanding that Toll honor the resolution. A representative group carried the petitions to Toll, who responded with a note taped to his locked door. When he finally consented to meet with representatives of the petitioners, he admitted that no vote against DoD by any of these groups would bind him.

Over the summer, DoD opponents tried to keep the issue alive so that Toll could not easily flout the faculty resolution. They circulated further petitions, issued informational leaflets, and kept a watch on new grant applications. Scrutiny of the new applications revealed that faculty and student demands had been ignored once again: three new DoD grant applications had been signed. One application, submitted by Franco Jona of Material Sciences, asked for over a million dollars for a three-year study on “the structure of solid surfaces”. Although this title has the ring of “pure research”, the application went to the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the Department of Defense. ARPA provides “centralized management of selected high-priority projects”—which suggests immediate military application. Other ARPA research projects have included the cloud-seeding and attempted firestorm bombing used in Vietnam as well as a great many other counter-insurgency projects.

Faculty and students have begun to plan for a continued and persistent campaign against Defense Department research. Toll’s prediction that there would be “some opposition” to his decision will surely be the understatement of the year.

DoD RESEARCH AND ITS DEFENDERS

Most students and faculty oppose American foreign policy, and are uncomfortable with the knowledge that the university helps to prop up that policy through defense research. At the same time, many people, particularly faculty, are also uncomfortable with the notion of banning DoD research, for variety of reasons.

THE PROBLEM OF “BASIC” RESEARCH

The first is the rationale that a great portion of DoD research is “pure or basic research”. The Department of Defense has firm opinions about the nature of the research it funds. Army Regulation No. 70-5, Section 1, paragraph 1 states that the purpose of awarding DoD grants is “support of basic scientific research in furtherance of the objectives of the Department of the Army.” The mission of research funding is “increasing knowledge and understanding directly related to explicitly stated long-term national security needs … for the solution of identified military problems. DoD itself, in other words, is publicly committed to fUnding only research which has foreseeable military application.

DoD takes steps to insure that its funding does in fact produce results. Proposals submitted to the Department must first receive the approval of a screening panel of military experts before they are submitted to the usual review procedures by scientific referees selected by the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council. The dental research recently carried on at Stony Brook was discontinued precisely because it was not providing knowledge useful to the military. A letter from the U.S. Medical Research and Development Command to the SUNY Research Foundation stated:

As you know, projects undertaken by the command can only be justified based on military relevancy.

A careful review of the goals and objectives of this project, as well as the current operation requirements of the potential user indicates there is no longer a military requirement for such a mass screening capability.

Given the large amount of funds involved, and the large percentage of all engineering research these funds account for, the DoD plays a powerful role in shaping the profile of engineering research at many universities.

Individual DoD-supported researchers often have no idea of the military significance of the work they do. Undoubtedly, many scientists whose laser research was supported by DoD would be dismayed to learn how the technology they helped to develop was indispensable for the production of “smart bombs”now victimizing the people of Indochina (though, of course, laser research has nonmilitary applications).

DoD funds research only for a sufficient military reason; it is important to recognize that there is, in turn, a reason for DoD. Defense research is essential to the government’s use of or threat to use, military force, and military force is an increasingly indispensable element of American foreign policy. The Defense Department is not a collection of crackpots with a penchant for creating bigger and better bombs; it serves a vital role in the attempt to continue American political, economic, and cultural domination of a major portion of the world. The seemingly limited question of what an individual researcher does in a particular laboratory is inescapably tied up with the fundamental issue of what America does with—and to—the rest of the world.

DoD funds research only for a sufficient military reason; it is important to recognize that there is, in turn, a reason for DoD. Defense research is essential to the government’s use of or threat to use, military force, and military force is an increasingly indispensable element of American foreign policy. The Defense Department is not a collection of crackpots with a penchant for creating bigger and better bombs; it serves a vital role in the attempt to continue American political, economic, and cultural domination of a major portion of the world. The seemingly limited question of what an individual researcher does in a particular laboratory is inescapably tied up with the fundamental issue of what America does with—and to—the rest of the world.

THE SPIN-OFF EFFECT

A second rationale for DoD research is that the development of military technology yields information, techniques, and hardware with highly beneficial civilian applications. However, those benefits are purely incidental to its primary goals. The single-minded concentration on military utility makes defense research at best an inefficient generator of civilian technology; at worst, DoD’s channeling of scientific inquiry is an actual impediment to socially useful research. DoD’s swollen budget and narrowly restricted goals must be scrapped in order to facilitate research which might have a chance at contributing to the improvement of civilian life.

IS FIGHTING DoD FUTILE?

It has been argued that if an individual university such as Stony Brook stopped DoD research, it would simply be carried out somewhere else. We would lose money (which pays for faculty, graduate students, laboratory equipment, etc.) and the DoD would lose nothing. Both arguments contain some truth, yet both are dangerously wrong, because both are arguments of impotence—they imply that change is impossible. However, the antiwar movement was successful in discrediting and removing ROTC at many campuses; resistance to military service, both in and outside the army, has led to the current dismantling of the draft system. It is also important to remember that Stony Brook is not the only campus which has been fighting DoD; defense work has been and is being challenged at Harvard, Stanford, Johns Hopkins, and several other places. No one has ever suggested that stopping DoD research here would be a complete victory; we are suggesting, however, that a strong campaign against DoD here would be an important stimulus to a crucial nation-wide fight. The difficulties involved in banning DoD should not be minimized, but neither should we minimize the potential of an organized, coordinated struggle against university complicity in the murderous American war machine.

DoD AND ACADEMIC FREEDOM

Many people who honestly oppose the war in Vietnam don’t want to ban DoD research because they feel that to do so would be a violation of academic freedom. However, a close look at this issue reveals that it simply does not apply to the DoD controversy. No one argues that academic freedom means that anyone can do anything. The entire academic community was outraged by the recent revelation that “researchers” deliberately infected mentally retarded children at Willowbrook Hospital with hepatitis, and a national scandal has surrounded the discovery that “researchers” in Alabama refused to treat syphilis patients for 30 years because they wanted to follow the development of the disease. Restrictions on research, which extend from methodology to subject matter to audience, indicate that academic freedom is not the fundamental guiding principle for research at the university. Banning Defense research is not a violation of academic freedom, which doesn’t exist. Banning Defense research is making a social judgment about the substance of research, the interests which it serves, and the uses to which it will be put.

DoD AND UNIVERSITY POLITICS

Still another argument—that we must resist the politicization of the university—is the most recent one to be raised at Stony Brook, and it is, hands down, the most absurd. Universities are political arenas, always have been, and always will be; opponents of DoD research are not setting some dangerous new precedent. Continuing to do DoD research is entirely political—it specifically supports the brutal international and domestic policies of the American government. Toll’s record of harassing and attempting to remove campus activists is political, as is his readiness to make university facilities available to military and defense recruiters. The question of whether this university is going to operate politically has already been answered in the affirmative. The remaining question facing us is much more specific: what politics are to prevail?

THE POLITICS OF FIGHTING DoD RESEARCH

The issue of Defense Department research has been raised many times, but a concerted and long-term effort to ban it has never fully developed. Such an effort holds out the prospect of a truly effective protest against science for imperialism and war.

The role of the military in Vietnam is only part of the broader foreign policy of the United States and is connected significantly to domestic politics. The same military and the same advanced weaponry which operates in Vietnam has left its indelible imprint in Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand; it has backed up, with advice and resources, brutal regimes in Burma, Bolivia, Greece, Spain, South Africa, Portugal, and much of the rest of the “Free” World.

In the U.S., “counterinsurgency” methods are applied by the Army and the police to suppress ghetto rebellions. The government adopts military solutions, by means of the police and the National Guard, in its efforts to suppress strikes and student revolts. It is worth remembering that the National Guard units at Kent State arrived there fresh from crushing a Teamsters’ strike in Cleveland. The resort to military force permeates government policy at home as well as abroad; in some cases, the technology the U.S. uses around the world returns here rather directly. A pair of spectacular examples are nighttime television surveillance of ghetto streets in Mount Vernon, N.Y., and a plan to implant electronic transmitting beacons in ex-convicts to monitor their movements! At Stony Brook, the Rand Corporation has worked in conjunction with the Urban Sciences Department on police deployment in the ghetto and other problems bearing on domestic counterinsurgency.

Such activities are not the accidental result of mistaken decisions, nor are they the insane maneuverings of crazed military chieftains. They are part of the maintenance of a particular kind of American power. These policies have the common effect of allowing American “free enterprise” to enter and maintain itself in foreign countries, and to keep its profits high and its position stable in the United States. Among other things, American companies are interested in the resources and extremely low wage standards in Southeast Asia, including the $1.40 per day maximum wage in South Vietnam. The military acts to defend tremendous investments in Latin America and helps Chase Manhattan Bank protect its highly profitable and highly political loans to the South African government. At home, the military uses its technology and force to quell ghetto rebellions and hence to defend the investments of slumlords and ghetto merchants. The suppression of strikes enforces the wage freeze and guarantees profits. Action against militant students not only defends profitable policies (like the War), but also guarantees that universities will remain safe repositories for defense research and for the production of compliant, “well-trained” technicians.

The DoD requires the most creative minds and the most advanced scientific insight to help maintain and improve old weapons, and to develop new and more effective ones for whatever new situations may arise. That is why the Defense Department so actively seeks research contact with universities. In addition

- If scientists and universities devote their energies and resources to DoD research, dependencies are created. At Johns Hopkins, for example, efforts to ban the ROTC program on campus were countered by the threat to end DoD funding; the dependence on that funding exercised leverage on other university issues.

- DoD research contributes to defining research interests and career options for graduate students. Given the large amount of funds involved, and the large percentage of all engineering research these funds account for, the DoD plays a powerful role in shaping the profile of engineering research at many universities.

- By its association with universities, DoD manages to improve its image. The scientific community, and academic researchers generally, have a reputation for serious, objective, useful activity; DoD research on campus, by making this association, lends an air of respectability to its operation.

The military has all of these reasons for wanting to fund research here and elsewhere. We should prevent DoD from associating itself with the university. We should not allow our resources—intellectual and physical—to be channeled into defense work, nor should our students continue to be fed into defense-related fields. Certainly we do not want our research efforts to aid a racist program of substituting Vietnamese deaths for American deaths. Our efforts must be to stop the killing, and our research and resources must be devoted to work which serves mankind. The only clear way in which we can accomplish this is to deprive DoD of some of its scientific resources.

Naturally, the elimination of DoD research at Stony Brook alone will not accomplish this, but it could be important to a national movement. The faculty resolution last spring was reported in Science magazine; an anti-DoD resolution was brought before the American Chemical Society; a great many students and faculty at other schools are interested in beginning anti-DoD fights. This campaign has the real potential of reaching enough campuses to seriously hamper DoD research activity.

When Dartmouth students began an anti-ROTC campaign in 1968, it may have seemed rather insignificant. In the next two years the fight spread to dozens of schools—the events at Kent State were part of an anti-ROTC fight—and resulted in a one-third reduction in the number of new officers. This shortage actually affected the Army’s ability to train and lead men in Vietnam; it probably had something to do with the reduction of combat troops. Resistance within the Army, which at first glance might seem impossible, has grown in size and intensity to the point where high military officials are beginning to doubt the efficacy of fielding ground troops anywhere. Fighting to ban DoD research at Stony Brook may seem insignificant in relation to the overall strength of the American military effort, but this, too, has the potential for a serious challenge to the conduct of American policy. Our analysis of DoD research has two conclusions: DoD research must be stopped, and it can be stopped.

HOW TO WIN THE DoD CAMPAIGN

In the history and analysis just presented we can see the weaknesses of past efforts to ban DoD research and also find the basis for a stronger, ultimately successful movement.

The central feature of past action has been its sporadic character. There have been strikes, sit-ins, petitions, arrests, votes and jail terms, spread over three years, but for all the energy, there has been no self-sustained movement. Student activity and faculty activity have been planned and conducted in separate and largely uncoordinated ways. This lack of unity has meant that neither the faculty nor the student elements of the past campaign have been able to build a focused, sustained and expanding movement.

Our local disunity is reflected on a larger scale in our isolation from groups elsewhere who are fighting against Defense Department activity and whose interests we share. This isolation keeps us from learning from the experiences of others. It makes us feel that our local activities are somehow worthless or trivial, the isolation pushes out of our attention the real and world-wide interests involved in DoD research.

The third major shortcoming of past work has been the low level of theoretical understanding of the issues involved. The foundation of any successful movement must be a proper understanding of the issues and forces involved. In the case of defense department research, the issue is not really one of academic freedom or university governance or research per se. The matter resolves itself to the role of the U.S. military and the interests of those who are protected or attacked by that military. The question of banning DoD research is not one of the politicization of the University. In the conflict between those protected by the U.S. military and those who fight back against it, the University necessarily plays some role. We must consciously choose the role for ourselves, with respect to DoD research and a host of other matters about the university. To do that, we must deepen our understanding of those basic conflicts in which the military and the university find themselves embroiled. The same university which supports DoD will not adequately support day care.

The same university which is among the largest employers in Suffolk County does nothing for the Eastern Farm Workers Association. More broadly, we must seek unity with groups elsewhere who share our desire to stop American military power in Asia and around the world. In this country there are a number of groups working on DoD research and on other aspects of military and corporate power. Everyone involved in the DoD campaign here would be helped by studying critically the efforts of others engaged in fighting the same enemy, just as all those other groups would be aided by studying the work we do here at Stony Brook. Only on the basis of unity on campus, and unity with allies everywhere, will we be able to build a coordinated, effective movement which has a chance of having a real impact.

In preparing this pamphlet, there was a lot of discussion about specific things to do. We do not present a detailed tactical program for ending DoD research because that should come from a much larger group of people engaged in unified effort to understand what to do. Successful movements on this campus and elsewhere in the past have involved a wide variety of actions, from petitions to demonstrations to violent confrontation. No campaign on the order of opposing DoD research has ever been won without massive militant action. From the anti-draft movement to the ROTC campaign to the war itself, massive united militance was essential at some point. In each case, the campaign was long. But victory came from understanding, unity and coordinated action of all sorts in a manner which successfully strengthened the movement and weakened the enemy. We think that this pattern can be repeated concerning DoD research, and it is in that spirit that we have written this article.

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 1 <<