This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Biological Science in China

by Ethan Signer

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 3, No. 4, September 1971, p. 3 – 5 & 15 – 19

Last May, Arthur Galston and I spent two weeks in the Peoples Republic of China, visiting various scientific establishments, talking with Chinese scientists and seeing the country in general. We obtained visas to visit China at the Chinese embassy in Hanoi, where we had gone to exchange information with North Vietnamese scientists and give several lectures. Like others who have done so (see Ptashne’s article in Science for the People, May 1971), we found the Viet-Namese to be quite aware of and interested in foreign scientific developments and to have a very deep and serious commitment to scientific research, much more so than one might have expected possible in the present conditions. We were particularly impressed with the effort they were able to spare from their obvious preoccupation with military affairs to build up their society, both in science and in such fundamental areas as education and public health.

We found that, under the impetus of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese are experimenting with new ways of organizing science and medicine. They seemed to be trying to integrate scientific research more closely with the immediate needs of industry and agriculture; to broaden the scope of medical care so that it reaches as much of the population as possible; and to do away with institutional and social customs that made intellectuals and professionals elite classes culturally distinct from ordinary people.

Begun in late 1965, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution seems to have been a struggle, not only for power between Chairman Mao Tze-tung and former Chief of State Liu Shao-chi, but also for the control of the development of Chinese society, between two conflicting ideologies. Mao’s philosophy stresses development of self-reliance among the Chinese people; striving for ambitious goals, as in the (largely unsuccessful) Great Leap Forward in 1958; egalitarianism and reliance on ordinary people; and moral incentives for labor. In contrast, Liu’s philosophy September 1971 (“the revisionist Soviet line”), now discredited, is said to have stressed the use of foreign technology where possible (“being foreign slaves”); cautious setting of goals within reach (“advancing at a snail’s pace”)· establishment of privileged intellectual and expert elite classes (“divorced from the masses”); and material incentives for labor(“following the capitalist road”).

The defeat of the Liu forces about 1967; and the subsequent struggles between moderate and extreme factions of the victorious Mao forces, were apparently very bitter and involved numerous excesses. But the climate now seemed quite calm. The moderate faction, now in control, denounces past excesses and blames them on “bad elements” in the extremist faction, although, whereas the Liu forces are considered revisionist class enemies, the former extremists are treated as temporarily misguided comrades. The Cultural Revolution is still in progress, say the Chinese, but now the final phase of transformation is following the earlier phases of struggle and criticism.

The main result of the Cultural Revolution seems to be the firm establishment of Mao’s philosophy as the dominant ideology in China. This seems to have led in tum to many profound changes, particularly is social values, ostensibly to rectify errors of the revisionists. It was in this context that we were shown Chungsan University (Canton), Peking University, and Futan University (Shanghai); the Academia Sinica research Institutes of Botany and Microbiology in Peking, and Biochemistry and Botany in Shanghai; an Affiliated Hospital of Peking Medical College; factories, a commune, the Forbidden City, and so on.

Scientific Research

In 1965, scientists at the Biochemical Institute in Shanghai announced the total chemical synthesis of biologically active insulin, a protein hormone, slightly ahead of West German and American groups. When I asked Hu Shi-chuan, in charge of research, what made the group decide to undertake this project, he replied, “Our great leader Engels said that protein is a form of life. By synthesizing it from simple chemicals we proved the correctness of materialism and discredited idealism, which holds that biological substances can only be obtained from living matter.” (A rather unexpected answer, but on the other hand, one that shares much of the attitude of American scientists who have recently synthesized biologically active nucleic acid molecules.) “Also, “he continued, “we wanted ultimately to be able to synthesize insulins with amino acid substitutions in order to study the relationship of protein structure and function:’ His answer was typical of many we received, both in science and elsewhere, in giving a practical reason together with an ideological framework and justification.

But when I asked if they were still working on insulin, he said there was really no urgent need, and instead they are now developing similar methodology to synthesize industrially the small peptide hormones oxytocin and angiotensin for medical uses. In this way they have essentially reoriented their work from basic to applied research. Likewise, all the other groups we saw who were formerly doing basic research are now participating in production. Fossil and evolutionary botanists are now working on the geobotany of pollen grains, useful in petroleum prospecting; taxonomists are now concentrating on industrially useful bacterial and medically useful plant strains; bacterial geneticists formerly doing pure research are now developing new strains with better growth characteristics and higher yield for industry; entomologists have switched from formal entomology to combating plant pests; and botanists who were studying plant physiology are now trying to increase agricultural production.

This shift from basic to applied research often involves working closely with a specific factory or agricultural commune. Thus the insulin group began their shift by first going to the factory that was to synthesize the peptide hormones in order to coordinate the joint effort, and have maintained the contact since. Groups at the Microbiological Institute in Peking studying microbial synthesis of glutamic acid (from Corynebacterium glutamicum) for production of monosodium glutamate (MSG), and enzymic conversion of corn starch to glucose for intravenous feeding, also work closely with the appropriate factories, and scientists at the Botanical Institute in Peking purifying a novel growth hormone from water chestnuts cooperate with an agricultural commune where it will hopefully be used to increase grain yield. Entomologists at Chungsan University, having developed a way way of fighting a lychee wasp (Tessaritoma spp.) with insect parasites (Anastatus spp.), are raising the parasites at 40 different communes. And a group at the Botanical Institute in Shanghai, formerly studying the mechanism of action of the hormone giberellin, has moved to a commune outside the city to develop the agricultural use of the hormone.

Conversely, factory workers and peasants have begun spending a few weeks or months in the appropriate research laboratory to learn techniques. At the Department of Biology in Chungsan University, we met the head of a 10 man factory team that has come to study extraction of pharmacologically active substances from medicinal plants. After research and development at the University, they plan to return to the factory to begin large scale production. In another laboratory, workers from an iron refinery were collaborating with micro biologists in studying the use of sulfur metabolizing bacteria (Thiobacillus mixoxidans) to remove sulfur from low grade iron ore.

Workers and peasants, particularly in agricultural communes, are being encouraged to set up their own simple laboratory facilities. At the 27,500 member Malu People’s Commune in Shanghai, a small factory was turning out a crude water extract preparation of the hormone giberellin from fungal mycelia. The fungus was grown on agricultural waste (wheat bran and rice chaff, with corn flour added), and nearly all the equipment was primitive and homemade — the constant temperature room for growing the fungus, for example, was heated by a hot plate nailed up in each corner of the ceiling. Next door was a thatch roofed hut containing a white tiled laboratory for microbiological work and for quality testing of sodium sulfite, made for sale by the commune from sodium carbonate and flowers of sulfur bought outside. And in the back room of the pharmacy at the small clinic in the housing project of the Number Three Cotton Textile Mill in Peking, we were surprised to find, among the stocks of traditional and Western medicines, a large ion exchange column being used to purify the anesthetic procaine.

The Chinese drive for self reliance was reflected in the abundant jars of chemicals, all Chinese manufacture, lining the shelves of all the laboratories. The biochemistry group in Shanghai, having decided to synthesize insulin, said they chose first to start a new factory for chemically synthesizing the component amino acids rather than buying them from abroad. And although we saw some foreign items (dating mostly from before 1949), most of the equipment — pH meters, photometers, electron and light microscopes, clinical and refrigerated centrifuges, and electrophoresis apparatus, microbiological incubators, and all the hospital operating room equipment — was made in China, and appeared to be of high quality. The laboratories themselves, scrupulously clean and neat, were furnished modestly, and resembled very much photographs of biology and chemistry laboratories in the U.S. in the 1920’s and 30’s — even the laboratory where insulin was synthesized.

Much of the Chinese taxonomy is apparently being done according to their own system rather than foreign ones, and their industrial plant species and microorganisms are local strains as far as possible. Self reliance, we were told, also means that, although the Chinese are prepared to learn from foreigners, since the Cultural Revolution few, if any, Chinese scientists have gone abroad for training. The ones who had previously done so — at the Microbiological Institute in Peking about 20 out of 300, both group leaders and ordinary scientists — had generally gone to the U.S. and Europe before 1949, but after 1949 to the Soviet Union. In response to our question, we were told that the Chinese are prepared to participate in international scientific meetings, but not if scientists from Taiwan are also present.

Libraries seemed extensive in the institutions we visited, with many foreign books in English, French, Russian, and German. The joint library of the Biochemical and Botanical Institutes in Shanghai was particularly impressive, with a very large number of books and literally every journal we could think of complete to early 1971 — and also a special reading room for studying the works of Chairman Mao — and the University libraries seemed fairly well stocked, too. Individual laboratories all had a number of Chinese books and usually also several foreign texts, often quite up to date, interspersed with copies of the red book of quotations from Chairman Mao.

During the early part of the Cultural Revolution publication of Chinese journals apparently dwindled and then stopped altogether1, but we were told it would soon resume. Research seminars and discussion of the literature are said still to be held, often with the invited participation of production workers, although not quite so regularly since the Cultural Revolution started. There is also communication among the different research institutes, such as the Botanical Institutes in. Shanghai and Peking.

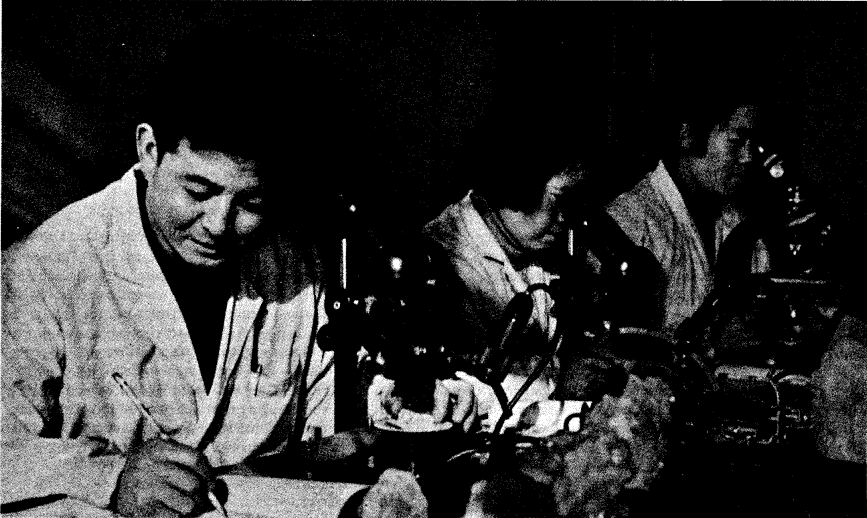

Our offer to lecture on our specialties was taken up in, of all places, small reception rooms on the sixth floor of the Peking Hotel, just off the Tien An Men square where all the large public demonstrations are held. Before a large picture of Chairman Mao on the wall and a miniscule black painted board propped on a cloth covered table, with the late afternoon sun slanting in through the windows and a panorama of Peking outside, I spoke for about an hour and a half on bacteriophage genetics to about 75 scientists and students, mostly from the Microbiological Institute. The interpreter, Prof. S. I. Lu, who learned his excellent English while study ing in the U.S. during the thirties, surprised me by using Chinese words for even the most abstruse technical terms — ‘ribosome’, or ‘aneuploid’, or ‘heterozygote’ — presumably another instance of self reliance. The older scientists seemed somewhat bemused by the rather unfamiliar subject, but the younger ones were quite attentive and seemed to be following closely.

After a short break the chairman of the session, Prof. Fang Sin-fang, opened the question period: “Chairman Mao has said, ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought dispute.’ Presentation of different opinions is the only way to discover truth. I answered some questions about bacteriophage genetics which indicated a broad familiarity on the part of most, and more detailed knowledge on the part of the few specialists. I was also asked about progress in cancer research and in molecular biology in general, recent achievements such as the chemical synthesis of a gene and discovery of transcription of RNA into DNA, and — somewhat embarrassing for me — progress in the application of microbiology to agriculture and industry. The discussion was forthright and lively.

Medical Care

In June 1965, Chairman Mao issued a rather surprising statement for a head of government: ” … the Ministry of People’s Health …. is serving 15 percent of this country’s population … the upper class. The broad masses in the countryside are receiving no medical care at all. The Ministry … should be renamed the Ministry of Urban Health, of Upper Class Health, or the Health of City Gentlemen. Medical training must be reformed.2 In response, many doctors have moved to the countryside, where more than 80 percent of the people live. At the Number 3 Affiliated Hospital of Peking Medical College, Kuo Fa shang, head of the Revolutionary Committee, told us that one third of the staff has now moved permanently to the countryside to care for the peasants and train ‘barefoot doctors’. The latter are largely uneducated peasants given a three month course in first aid setting broken bones, superficial surgery, and traditional remedies such as acupuncture and herbal medicines. The remaining two thirds of the staff, besides picking up the slack at the Hospital, are also organized in mobile teams that occasionally go to the neighboring districts and countryside to give medical care and lessons in preventive medicine. Mao’s instructions, “In medicine, put stress on the rural areas ” is apparently being taken to heart.

The Hospital, now controlled by the city rather than the Ministry, is one of more than 80 large hospitals in Peking, of which one dental and three medical hospitals are affiliated with the Medical College. Founded in 1958 as a polyclinic, it has departments of medicine, surgery, obstetrics, pediatrics, neurology, otorhinolaryngology, and ophthalmology. There are 700 staff, of whom 160 are doctors and 260 are nurses, for the 606 beds. Including barefoot doctors, medical personnel in this district of the city total 1.1 percent of the population.

Medical care for workers and peasants is either free or covered by cooperative medical plans costing very little (a few tenths of a percent of an average salary), although dependents must pay half the medical costs. It is generally organized through the factory or agricultural commune. At the Number 3 Peking Cotton Textile Mill, we saw a small hospital with a staff of 60 (including 20 doctors) for the 6000 workers. It includes outpatient clinics and wards, operating and delivery rooms, diagnostic and X-ray laboratories, and a pharmacy well stocked with both Western and traditional medicines.

Traditional medicines appear to be taken very seriously in China, following Mao’s instruction: “chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house. Efforts should be made to exploit them and elevate them to a high level.” The Chinese are teaching peasants to recognize, grow, and handle medicinal herbs, and, since the Cultural Revolution began, the taxonomists at the Botanical Institutes and in the University Departments of Biology have been preparing manuals to help identify them. Scientists are trying to extract the active principles from many of these, as at Chungsan University where we saw students testing oil extract preparations of Collicarpa spp. used to stop bleeding. And Western-trained doctors are encouraged to study traditional medicine and combine the two systems.

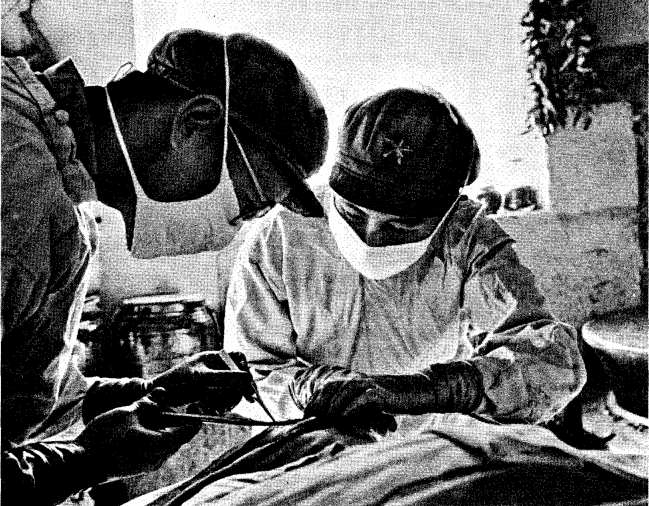

The Chinese are also finding new uses for acupuncture the traditional technique of piercing the body with long, fine needles, used for hundreds of years to cure aches and pains, insomnia and other minor ailments. By experimenting with new points of application, and varying the length and number of needles, they have developed the use of acupuncture as a local anesthetic for major operations. We saw four operations at the Affiliated Hospital in Peking — removal of part of the stomach, hernia, removal of a thyroid tumor, and removal of an ovarian cyst — with acupuncture as the only anesthetic, and other Western observers have reported seeing open heart surgery.

As we watched, four to six needles were thrust into each patient’s body at specified points at different places in the legs for the three abdominal operations, with an additional pair near the incision for the hernia, and in the neck and wrists for the thyroid tumor. A report of numbness by the patient in each case indicated successful placement. Although needles are traditionally rotated by hand after being set, here they were vibrated electrically with a mild current, which might also have played some role in the anesthesia. Anesthesia was established after about 20 minutes, and we were told it may last as long as nine hours. Over 3000 operations have been done with acupuncture at this hospital, including removal of eyeball, lung and spleen, and amputation of limbs. The four surgical teams seemed fast and competent. The patients all were conscious during the entire operation — the ovarian cyst patient’s pulse was constant at 88, and blood pressure at 110/80, throughout — and seemed quite calm, chatting with the doctors. The exception was the hernia patient, who was extremely nervous throughout the entire operation and clutched the red book of quotations from Chairman Mao to his breast for comfort.

Another new use for acupuncture is in curing deafness. At a school for deaf mute children in Peking, we saw a class of ten to twelve year olds read as best they could from the blackboard Mao’s precept, ‘We must not fear hardship or death.” Those whose tum it was for treatment (every ten days) then had needles inserted in the temples and the backs of the wrists, rotated briefly and removed. Modest results are claimed: 90 percent of the children have had some hearing improvement since treatment started in 1968, but only 6 of the 238 children have improved to the point of being able to transfer to an ordinary school.

The acupuncture method is entirely empirical. Although the Chinese have been trying to find a physiological basis for it they have not yet succeeded in doing so.

Traditional medicines are also combined with modem ones in psychiatry. Depending on the symptoms, acupuncture and herbal medicines may be combined with vitamins and insulin therapy, or electric shock treatment (discontinued at the Affiliated Hospital). But the main treatment is discussion therapy not based on Freud or other idealistic Western theories, but rather on dialectical materialism and the philosophy of Chairman Mao.

Social Structure of Science

One of the most profound changes instituted during the Cultural Revolution is the attempt to disestablish intellectuals and technical experts as a privileged, elite social class. This is being done partly through political education that stresses the virtues of workers and peasants. In the early days of the Cultural Revolution, extensive reorientation classes for intellectuals were apparently quite common. Many still spend several months at the May 7 Cadre Schools, named after the date of the letter from Mao to Lin Piao in which they were proposed. There they learn to serve the people by accustoming themselves to manual labor, learning peasant skills such as farming and building huts, and studying Mao’s ideology. “Serving the people “is expected in ordinary jobs, too, where those in positions of authority still take turns doing the necessary menial work3, and everyone is expected to spend time studying and discussing Mao’s Science for the People precepts — as at Chungsan University where the professors meet to do so for an hour a day. At Peking University faculty duties are said to include research, teaching, and manual labor in agriculture or industry, and faculty are expected to spend several months to a year alternately in each occupation.

Factory workers and peasants are apparently being brought into the decision making process. Instead of traditional management personnel (cadres) only, all institutions are now run by elected Revolutionary Committees constituted according to the “three in one” principle: cadres, ordinary workers or peasants, and army or militia. The army does not seem to be included as a military presence, but rather because of its political loyalty to Mao — the army was in fact Mao’s principal agent in making the Cultural Revolution. Thus the net effect on management is to increase participation of and answerability to ordinary people, and at the same time to control political direction. At Peking University, with over 2000 faculty and a student body expected to approach IO,OOO, the Revolutionary Committee has 39 members: 9 teachers, 7 students, 6 cadres, 7 army members, 6 workers, 3 more workers from University-run factories, and I representative of faculty and staff families. At the Affiliated Hospital, with a staff of 700, the Revolutionary Committee includes 3 doctors, 2 workers, I technician, 2 nurses, 4 cadres, and 3 army members. Although we had little chance to observe the interplay of central and local planning, I had the impression of some flexibility and independence at the local level within broad guidelines set by the government.

The practice of having scientists do part of their research work at factories and communes, and workers and peasants spend time in research laboratories, also helps break down elitism. Intellectuals are officially encouraged to pay close attention to suggestions from ordinary, untrained people, and several scientists offered us unsolicited instances from their own experiences. At the Microbiological Institute in Peking, it was a visiting worker who suggested correctly that the efficiency of the industrial process converting starch to glucose (with the enzyme alpha glucamylase from Aspergillus) could be improved by making the enzyme insoluble. Other scientists working there on contamination of industrial bacterial cultures with several viruses were having trouble obtaining multiply resistant strains, but at the suggestion of a factory worker seemed to have success using instead mixed cultures of singly resistant strains. In Shanghai Dr. Loo Shi-wei, trained at Caltech and now at the Botanical Institute, knew (as do U.S. scientists) that the hormone giberellin normally increases plant growth rate but not final yield; however, he was able to increase yield by 20% by applying it at the flowering stage rather than the orthodox seedling stage, at the suggestion of a peasant at the Malu Commune where he has lately been working. And when scientists began going to factories to find out about production problems, we were told, the experienced workers took pains to help them learn. These examples were quoted, not to pretend that peasants and workers are automatically always correct, or that uneducated people are necessarily smarter than educated ones. Rather, they were to emphasize the current notion that suggestions should be evaluated only on their merits, and that even uneducated people can make valuable common sense suggestions-in contrast with the situation before the Cultural Revolution when, it was said, experts and intellectuals would not deign to accept advice from uneducated people.

A similar leveling process is said to be occurring within the research groups. At the Microbiological Institute in Peking the title of professor has officially been abolished (although it seems still to be used deferentially for older scientists), and all the scientists are considered research workers at the same level. There are still heads of research groups, but whereas they used to make all decisions, now “bright young persons can insist on the truth, which is sometimes in the hands of the minority”. Thus anyone, including workers, can suggest a research project to the group for discussion, although the final decision on adoption rests with the Revolutionary Committee of the Institute or even a higher authority.

We were quite aware of the absence of one kind of elitism during our tours of institutes and unviersities and the formal interviews that alway preceded them. Although those in authority were very clearly treated with respect and deference, people who were obviously rank and file seemed to show no hesitation or self-consciousness in interrupting in the conversation or contradicting their superiors when they had something to say, nor did these contributions seem to be taken amiss. We had a similar impression at the numerous formal banquets arranged for us, where the waiters often contributed to the conversation in a very natural way.

Science Education

The reduction in emphasis on intellectuals is also changing the character of higher education. Last fall, the Universities accepted their first classes since the Cultural Revolution began in I966, but the students are no longer chosen directly from secondary school on the basis of competitive examinations. Instead they are primarily workers, soldiers and peasants who must have spent at least a few years (and often longer) working in production, before they may be recommended to the University by their factory or commune (or apply themselves with factory or commune approval). Most are expected to have finished secondary school, but private study apparently may do instead. The competitive examinations seem to have been replaced by a more informal assessment of educational, political and social qualifications. Quotas for the different departments are established by the government, but the University allocates the individual students, respecting preferences where possible.

Although a University placement committee assigns jobs where necessary, most of the students say they will return to their old jobs after two to three years at the University. (When asked directly what they expected to do after graduating, almost all the University students we talked to answered at first, whatever the country needs.) Thus most science education is geared directly to industrial or agricultural production. A few of the science students will go on to further study and careers in research. But although the number for any subject is fixed by the government for each University, it is the students and faculty who are said to select the individuals by discussion of both professional and political qualifications, with final approval by the University Revolutionary Committee.

The University curriculum, too, is being altered to suit production. At Chungsan University the Biology Department used to include Zoology and Botany sections, but since the Cultural Revolution it has been divided into Industrial Biology, Agricultural Biology and Traditional Herbs. In order to combine research, teaching and production, the University now has a small pilot plant producing the antibiotic tetracycline on the campus — built by students, faculty and staff — and is carrying out several collaborative projects with outside factories and agricultural communes. And the educational base has been broadened with the institution of two to six month courses in agricultural and industrial technology held in the countryside by faculty and students. Thus far nearly fifty teams from Chungsan have trained 443 people in 20 counties.

The new experimental curriculum at Peking Medical College has been shortened from six to three years and streamlined, according to the principle of fewer and more efficient. The first ten months include courses in anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pathology, histology, embryology, microbiology, pharmacology, parasitology, epidemiology and preventive medicine. Next follow six to eight months of clinical training in affiliated hospitals, and the students are then sent to the factory or the countryside with their teachers for eight months more of practical training. Finally, they return to the hospital for advanced clinical and theoretical training. Doctors are expected to be proficient in diagnosis and treatment of common diseases, routine major surgery, obstetrics, and diagnostic bacteriology and parasitology. Some of them may later go on to specialize, if the people in their departments feel they need it.

The College and its four hospitals can accomodate 2800 students, and as elsewhere the present class of 750 is the first since the Cultural Revolution began. Although secondary education is the customary requirement, many of these students have apparently substituted training as barefoot doctors, and practical experience.

General Comments

A visit as short as ours raises more questions than it can answer. Besides lacking the time to see many things, we had to generalize from a very small number of examples, and accept many facts at second hand. Furthermore, we were observing a frankly experimental shift in policy that is still in its early stages, and it seems far too soon to tell how permanent or successful will be the changes instituted as part of the Cultural Revolution. Nevertheless, certain general trends were quite evident, and we often learned much about the Chinese from the way they chose to express themselves.

The quality of most of the scientific research we saw was modest. This is perhaps not surprising considering that, when China emerged from feudalism as recently as 1949, there were only 125,000 college-trained people in the entire country (there are now said to be over two million4, and in that sense progress has been quite significant. On the other hand, there were significant exceptions such as the synthesis of insulin, the production of a birth control pill, and the use of giberellin to increase plant yield, and the Chinese have made great strides in the physical sciences5.

The social upheavals of the early years of the Cultural Revolution largely halted scientific research6, like many other aspects of Chinese life. The extent to which it has been restored is difficult to judge; the laboratories we visited appeared fully staffed and running at a normal level. China has obviously suffered a short term loss in scientific productivity, but in the long term this will have to be evaluated in the light of any gains that may ultimately result from the reorganization of research under the Cultural Revolution. For example, although basic science is now de-emphasized, most of the basic research that was described to us by scientists who have now shifted to applied work was not terribly impressive and often duplicated Western work; putting those resources into applied research and depending on foreign basic research instead might prove to be more profitable to the Chinese.

It is clear that Chinese science will strongly emphasize applied research for some time to come. The Chinese maintain they are not against theoretical research, but that industrial and agricultural production should be the source of knowledge used to construct theories. Even very long-term, exploratory research is acceptable, they say, although “we must still handle correctly its relationship to production”7. Presumably this means some basic research is still supported, even though all the scientists we met who had formerly done basic research are now doing applied work. The shift to applied science is complemented in scientific education by the emphasis on workers and peasants, and the fairly direct connection with agricultural and industrial production. It is also reinforced by the development, in parallel with large scale science in research institutes, of science on a small scale in factories and communes — part of Mao’s general policy of “walk on two legs.”

At the same time, the emphasis on workers and peasants — as in health care, for instance — and on practical, common sense knowledge, and the efforts to combat elitism and serve the people are already affecting the priorities and attitudes of scientists. The attitudes of ordinary people towards intellectuals will probably be a long time in changing — one of our guides commented that the fact of my speaking French indicated that scientists are more intelligent than ordinary people. Also, it is likely that there was a good deal of opposition among Science for the People intellectuals to their loss of class privileges and deference, and of course we did not expect to be introduced to opponents of the policy. However, most of the scientists we met seemed remarkably sympathetic with this sort of egalitarianism. Doctor Shen Shu-chin, trained in the 1940’s at the Pennsylvania Medical College for Women, used to practice at a hospital in Peking, but has spent the last 18 months in a distant province training “barefoot doctors” When the Cultural Revolution started, she assumed at first it didn’t apply to her, and it was only political reeducation and study that changed her mind. “I really thought I was leading a useful life,” she said, “but I see now that I was living only for my personal satisfaction, and I’m much happier now that I can serve the people directly.” This might sound forced to Americans, but she seemed quite genuine and sincere, and she was already looking forward to returning to the countryside after a month or two with her family. If this trend continues, Chinese scientists and intellectuals may come to see themselves, and be seen, as simply useful members of society rather than an elite class of mandarins.

The policy of self-reliance and independence from foreign influence is obviously very important to the Chinese self-image. It may be quite practical as well, considering the past hostility of the two superpowers, the United States since 1949 and the Soviet Union since 1960. Despite their professed preference for things domestic, however, the Chinese will presumably offset their own emphasis on applied science by relying to some extent on foreign basic science, which seems sensible in view of the extent to which this has been developed in the West. Nevertheless, the traditional Chinese lack of interest in things foreign does not seem to have changed much. The scientists seemed aware of the general outlines of recent Western scientific progress, if not the details. But although they seemed politely curious about us as Americans and about American science, and those who had studies in America sometimes asked after their former institutions and friends, we definitely did not have the impression that they felt cut off from the West or were thirsting for knowledge of it, but rather that they were simply preoccupied with their own concerns. As Dr. Shen said, explaining why she had gradually stopped corresponding with former acquaintances in the U. S., “We don’t seem to have very much in common.”

>> Back to Vol. 3, No. 4 <<

Footnotes

- Sigurdson, Jon. Natural Science and Technology in China. Report No. 154., Stockholm, Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1968.

- Ch’en, Jerome. Mao Papers. Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Horn, Joshua. Away With All Pests. New York, Monthly Review Press, 1971

- Sigurdson, Jon. Natural Science and Technology in China. Report No. 154., Stockholm, Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1968.

- Macioti Manfredo. “Hands of the Chinese.” New Scientist and Science Journal, June 10, 1971, 636-639.

- Sigurdson, Jon. Natural Science and Technology in China. Report No. 154., Stockholm, Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1968.

- “Integration of Research and Practice.” BBC World Summary Broadcast, Far East, FE/3586/B/5. From Peking Home Service, January 6, 1971, translation of broadcast by Chinese Academy of Sciences (Academia Sinica).