This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Women Fight Back: The Politics of Female Genital Mutilation

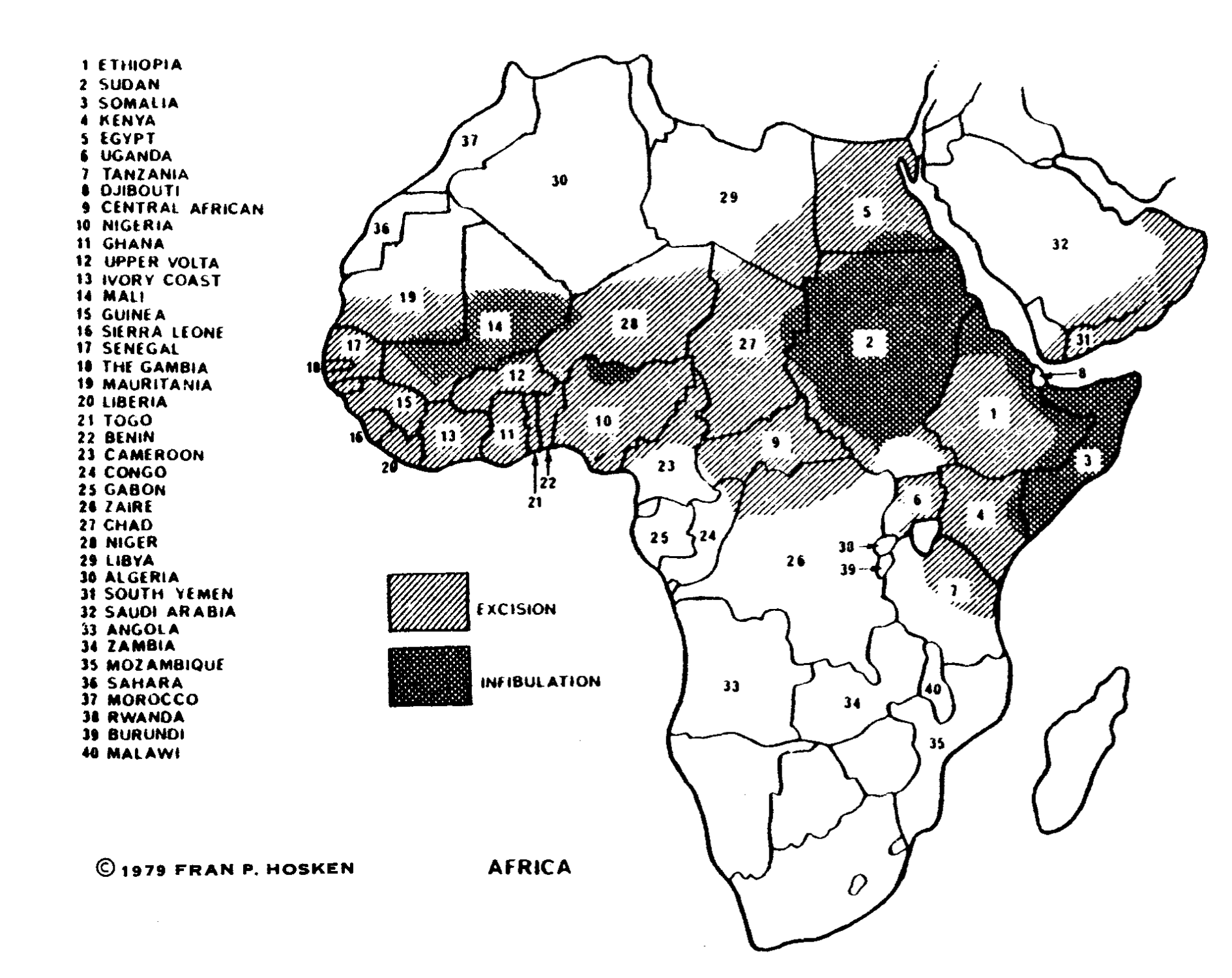

by Fran Hosken

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 6, November-December 1980, p. 12 – 16

Fran Hosken is the Editor of the Women’s International Network News. She is an architect planner concerned with modernization and urbanization worldwide.

Seminar on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children

“Traditonal Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children” was the title of an international, five-day seminar held in Khartoum, Sudan in February, 1979. The seminar, which was sponsored by the World Health Organization, marks the first time that genital and sexual mutilation, practices that blight the lives and destroy the health of millions of women and girls in Africa and the Middle East, have been addressed in an international forum. Participants included health department delegations from Sudan, Egypt, Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Oman, Southern Yemen and Nigeria. Upper Volta sent the president of the National Women’s Organization as an observer. The meeting was also attended by representatives from international nongovernmental organizations, and by the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID).

Physicians, midwives and other health professionals described the ways that external genitalia, including the clitoris, of tens of millions of female children are cut off or mutilated. The most frequently practiced operation, clitoridectomy or excision, involves cutting out, without anesthetic, most or all of the external genitalia of female children, at any age from birth to puberty. The most dangerous operation, infibulation or pharaonic circumcision, involves removing the exterior genital organs of the child and closing the vagina by sewing or scarification. The legs of the child are tied together for several weeks until the wound is healed; only a small opening, created by inserting a splinter of wood into the wound, is left for elimination.

These operations often have serious medical consequences including: hemorrhage, which may be fatal; dangerous infections, including tetanus; terrible scarring, which results in difficult childbirth and even infertility; menstrual problems; fistulas (rupture of the vaginal walls); incontinence and other permanent disabilities. The operations can result in life long frigidity and painful intercourse; chronic inflammations; and infections of the internal genitalia may finally cause infertility.1 The mental problems which result have never been systematically studied.

The Egyptian Country Report presented at the WHO Seminar, showed that excision continues to be widely practiced all over Egypt by a majority of families, except the western-educated upper class. The operations continue despite a 1959 statute (which was further strengthened in 1978) that states that the operations are forbidden “for scientific and health reasons … “. According to all estimates, more than half of Egyptian female children under the age of eight continue to be mutilated. The results of a survey conducted at a Family Planning Clinic in Cairo, showed that 90% of the women attending the clinic were mutilated, 46% of their daughters were already excised, and 34% more intended to do so. Moreover, the survey revealed that female clinic personnel not only were excised themselves, but the majority already had or were planning to have their own daughters excised. These women are trained with the assistance of Western-devised programs, including training programs financed and designed by U.S./AID, to teach family planning and health.

SOMALIAN WOMAN DESCRIBES OPERATIONSEdna Adan Ismail from Somalia, a midwife and head of the training division of the Somalian Health Department, described the operations practiced in her country2:

Edna Adan Ismail also describes from her own experience some of the mental complications that affect the female child from an early age, that “remain with her throughout her life”:

*From WIN News, Spring 1979, Vol. 6 No.2, pp. 30-31. Edna Adan Ismail made these remarks at a Regional Conference in Lusaka, Zambia. |

WHO Seminar Recommendations

Four recommendations on “Female Circumcision”, the traditional term still used all over Africa (though medically incorrect), were unanimously adopted by the delegations. They read:

- Adoption of clear national policies for the abolishment of female circumcision.

- Establishment of national commissions to coordinate the activities of the bodies, including where appropriate, the enactment of legislation prohibiting female circumcision.

- Intensification of general public education, including health education, on the dangers and the undesirability of female circumcision.

- Intensification of education programs for traditional birth attendants, midwives, healers and other practitioners of traditional medicine, showing the harmful effects of female circumcision, with a view to enlist their support in general efforts to abolish these practices.

Action on the International Level

Since the Khartoum Resolutions, very little action has taken place despite WHO’s call for “collaborative action at the international level … ” The proceedings of the Seminar were published in 1980, as well as an article in May 1979 in the international journal, World Health.3 Aside from this, there has been mostly silence on the part of the international community, with a few exceptions.

UNICEF, which until last year refused to acknowledge the operations, has drastically reversed its position. This has not happened easily: it took concerted political effort, led by WIN NEWS to make the facts about the operations known. Then, UNICEF had to be urged – especially by women contributors – to address the issues. As the foremost agency concerned with maternal and child health it is their responsibility to speak out against genital mutilation.

In March, 1980, UNICEF finally joined WHO in a “joint action program of research, education and training designed to support governments in their approach to female circumcision and its health hazards.” At the United Nations Mid-Decade Conference on Women, held in Copenhagen during July 1980, UNICEF announced its support of the Khartoum Seminar recommendations. The UNICEF program included “encouragement of community initiated activities,” provision of “information to media to address the issue,” integration of the “discussion of female excision into all educational and training programmes – including the development and preparation of training materials,” and “the direction of strong advocacy efforts towards national policy and decision-makers, as well as health workers and the general public in affected area.”

In Copenhagen, aside from WHO and UNICEF, the only delegation that addressed the issue was Sweden. Karin Anderssom, Swedish Cabinet Minister for Equality, delivered the following statement:

We, too, share the widespread concern over the practice of female circumcision. The serious medical and social consequences of this practice are of concern to women in many countries. We welcome recent initiatives by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to take up this issue. My government stands ready to support all health programmes which include measures designed to abolish female circumcision …

All other governments working in affected areas of Africa and the Middle East have been silent. In addition, private organizations including charitable and church groups have not taken a position against the operations. Christian converts all over Africa mutilate their female children. This is condoned and tolerated by international Christian organizations, although local Protestant ministers have tried to stop the mutilations, especially in Kenya. The Catholic authorities have never opposed them. The Pope in the 18th century sent a medical mission to Ethiopia who determined that the operations were necessary on medical grounds. Rome has ever since provided approval by silence.

POLITICS OF ERADICATING GENITAL MUTILATION

African women express a range of feelings about genital mutilation, and are often divided about whether or not to stop the practices, and if so, how. Within Africa, many women are unaware of the practices, or unaware that it is not universal. Many of them resent strongly the anti-mutilation activities of Western women, feeling that it is an African women’s problem and must be dealt with by them alone. Others feel that, while they want to be consulted and involved, African women need the sensitive help and active support of women from the West. Indeed, even though it will take a long time to eradicate genital mutilation, many are convinced that eradication cannot come about without outside help. |

U.S. Agencies are Silent

AID, despite the Khartoum Seminar recommendations and the recent changes in UNICEF’s policy, remains silent. Yet, AID collaborates in health and family planning programs all over affected areas of Africa. AID is involved in a $14,000,000 Rural Health Delivery Program in Somalia; a $4,000,000 Rural Health Program in Mali and an $8,000,000 Sudanese Primary Health Care Project. Excision is not included among the health hazards named in any of these projects, although most female children in these countries are excised; in Somalia and Sudan, the prevailing operation is infibulation, the most dangerous of the operations.

There are many people in those countries, including in the Health Ministries, who are actively trying to abolish the operations. In Somalia, a National Commission for abolishment of the operations was formed in 1978, with the Ministries of Health and Education represented, and the Somali Women’s Democratic Organization as executor. In the Sudan, the Fifth OB/GYN Congress voted unanimously for abolishment as their official position.

At the present time, genital mutilations are being introduced into modern medical practice and hospitals. In urban areas of Africa, the operations are often performed on newborn babies, as sexual castrations and stripped of all traditional rites. This is a gross abuse of modern medicine and medical ethics. Increasingly, health equipment and training contributed by AID and other western donors is used to mutilate female children in affected countries.

AID has been repeatedly informed about this situation, but no action has been initiated to prevent such abuse and no preventive education has been included in any of their training programs. The official AID position remains, “We cannot interfere with tradition practices.”

In a meeting in early summer, 1980, with the Health Coordinator of AID, Dr. Stephen Joseph, Deputy Assistant Administrator, preventive measures were discussed, specifically childbirth education materials and programs to teach positive, reproductive health. Several months later AID still had taken no action. AID’s only action to date is to initiate the development of a bibliography via a library computer search: this despite the fact that a bibliography was provided to AID by WIN News some time ago. AID has appointed a coordinator to address the issue of genital mutilation, but she has yet to integrate programs to eliminate genital mutilation into some of the major AID health programs.

Recently, testimony about AID’s failure to act and take preventive measures was presented before the Subcommittee on Foreign Operations of the Committee on Appropriations. AID’s response to a request by the committee for an explanation produced no fact nor any proposals for preventive measures. Preventive education is now especially important as the operations are performed on even younger children who have no choice. As a result of population growth, more children are mutilated today than ever before.

It is intolerable that AID, whose programs are financed by tax dollars, has continued to ignore the wishes expressed by African and Middle Eastern Health Departments, and that they have refused to collaborate in international actions sponsored by WHO and UNICEF. The unwillingness of AID and other national and international agencies to stop genital mutilation reveals the politics of deliberate neglect and obfuscation which are fatal to many children in Africa and the Middle East.

Update

To support preventive actions, write to Senator Daniel K. Inouye, the Chairperson of the Foreign Affairs/Foreign Relations Committees (Committee on Foreign Affairs, The Congress, Washington, D.C. 20515); and to AID Administrator, Mr. Douglas Bennett (U.S. Agency for International Development, Department of State, Washington, D.C. 20523).

For further information write to WIN News, 187 Grant Street, Lexington, MA 02173. WIN News has published many reports on Genital Mutilation, including The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females and Female Sexual Mutilations: The Facts and Proposals for Action.

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 6 <<

References

- *One clinical study of the medical effects of genital mutilation is by Dr. Abu el Futuh Shandall, “Circumcision and Infibulation of Females: A General Consideration of the Problem and a Clinical Study of the Complications in Sudanese Women”, published in the Sudan Medical Journal, 1967.

- *From WIN News, Spring 1979, Vol. 6 No.2, pp. 30-31. Edna Adan Ismail made these remarks at a Regional Conference in Lusaka. Zambia.

- *The proceedings are available from The World Health Organization’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, P.O. Box 1517, Alexandria, Egypt. World Health is published in many languages, and is available from WHO, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.