This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Black Hills Gathering: People Unite for Survival

Compiled by the Boston Editorial Committee

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 6, Month 1980, p. 17-26

This article was compiled from a variety of sources by the Boston Editorial Committee. The quote by Ellen Shub recently appeared in Sojourner, a Boston area feminist journal. Ellen Shub is a Boston area free-lance photographer. She is active in feminist and anti-nuclear organizations. The section called. “The Gathering- An Overview” is excerpted from Liberation News Service, copyright 1980; and part of the section called, “Plans for Action” was excerpted from Paha Sapa Reports, August/September, 1980. Other sources of information include, leaflets and reports by Women of All Red Nations. The Black Hills Alliance, Miners for Safe Energy and Pacific News Service.

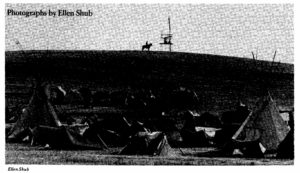

For 10 days, from July 18 to 27, a community of over 10,000 people from over forty countries convened in the rolling hills of South Dakota for the 1980 Black Hills Alliance International Survival Gathering. What marked this unique and historic event was the diversity of the participants — anti-nuclear activists, farmers, Native Americans, city dwellers, alternative technology activists, natural healers — all came together to work toward a common goal, survival. Participants developed a larger understanding of the problems which threaten human survival in this nuclear and technological age. People left the gathering prepared to attack these problems locally.

People got an education and deeper appreciation of how important it is to be unified. And that means understanding the more subtle aspects of racism. It takes education about other cultures to be really unified.1

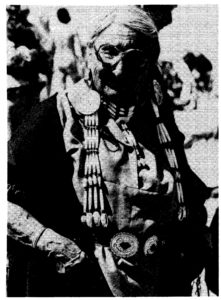

Participants returned excited by the different people, nations, and walks of life represented at the conference, moved by the dangers of radiation, and determined to work in a united way. Ellen Shub, who contributed the photographs in this article, summarized her feelings about the conference, “My family has become larger, with the people from other states and countries that I met there.” She has brought the work of the Gathering back to Boston — sharing her tapes, photographs and literature and supporting the legal defense of Rita Silk Nauni.

In a recent article, published in Sojourner, a Boston women’s journal, Shub described her experience:

I go to workshops daily between 9 and 7. I learn about Indian genocide and the planned extinction of the family farm; radiation and the contamination of all living things; health and education for suvival; appropriate technology and land use; and the multinational corporations and organizations who are at fault: Union Carbide, United Nuclear, Kerr-McGee, Exxon, the Export-Import Bank, the Trilateral Commission, the Council of Energy Resource Tribes, the TVA, and the DOE.

I visit Edgemont, South Dakota, where the Tennessee Valley Authority mills uranium. By a dirt pile near the Cheyenne River, the “Nuke Buster” geiger counter jumps off scale and wildly beeps. The background radiation level registers 50 times “acceptable.” In nearby, pristine Craven Canyon, as eagles soar above and archeologists examine petroliths, a spokesman from Union Carbide assures the media that mining will not disturb the natural environment, while an attorney from the Black Hills Alliance refutes his claim. We visit the Braffords. Their six year old son tells me radiation causes cancer and you die from it. Their house, like others in Churchrock, New Mexico, and Grand Junction, Colorado, has been built with radioactive tailings by a contractor saving money. The government has known for years that the radon gas readings were excessive, but they failed to inform the Braffords, who lived there with their three children, now aged 6, 3, and 6 months (see box). A woman from Washington tells them how to be in touch with people from Love Canal, New York. There is a victim’s support network. Ironically, the Edgemont Atomic Drive-In Theatre is playing “American Gigolo.” I swim in chilled waters to wash off the days radiation: I cry, and eat miso.

It is daybreak, 5 a.m. I go with a Belgian woman from Radio France, a California reporter, and a former member of the Karen Silkwood Defense Committee to a sacred sunrise ceremony. A circle of prayer and respect with people of all colors and nations conducted by the Grandson of Black Elk, Wallace Black Elk, his wife and partner Grace, and the women Elders of the Big Mountain of the Dine Nation. As an Anglo, a cultural imperialist, myself a colonized person in a racist culture, I learn something of traditional spiritual life of the Red Nations of the Lakota, the Hopi, and the Dine. As a city dweller, I relearn a sense of connection to the earth and elements, the sacredness of natural existence and my relatedness to all creatures and spiritual powers. And to honor and respect ceremonies to the Mother Earth, the Great Spirit and to all our relations still present with us. I relearn the principle expressed so simply by Crazy Horse, 19th century Lakota Sioux — ‘One does not sell the land on which people walk.’ One does not allow energy corporations to mine the sacred Black Hills (the Paha Sapa) in violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

The Gathering — An Overview

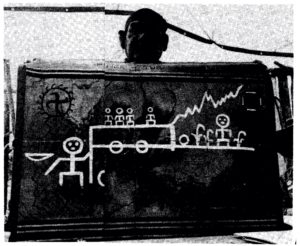

The Gathering stressed the threats posed by corporate and governmental energy development policies and the need to develop tools and knowledge to overcome those threats. To that end, the Gathering divided into five major work areas: The Citizens’ Review Commission on Energy Developing Corporations; the Forum on Indian Genocide and the Planned Extinction of the Family Farm; Appropriate Technology/Land Self-Sufficiency; Health for Survival; and Education for for Survival.

The Citizens’ Review Commission, through panel sessions and workshops, examined the multinational corporations and their activities throughout the world. Union Carbide, Rio Tinto Zinc, Kerr-McGee and other firms were identified as directly involved in the uranium and energy resource exploitation now going on in the Black Hills. The story that emerged from these sessions was one of greed, lack of concern for the environment, and domination of people throughout the world. Steven Beckerman, a researcher examining the corporations involved with the destruction of the Hills, testified about the difficulty of learning who actually owns and controls these firms. Beckerman reported that only 30 per cent of the stock in any one of these firms can be accounted for; even the U.S. Congress cannot force corporations to disclose the identities of their stockholders. Of the stockholders revealed, certain names, such as Morgan Guaranty Trust, Lord Abott and Company, and William Acheson appeared repeatedly.

Another focus of the corporate review was the Trilaterial Commission. Researcher Holly Sklar presented information demonstrating the mentality of this international economic cartel. The Commission places profits above all else — it supports the use of military intervention to protect profits, and advocates limiting civil rights to insure the security of large corporations. Originally formed by David Rockefeller, president of the Chase Manhattan Bank, the Trilaterial Commission includes Henry Kissinger, John Anderson, and its members are found in firms such as Time-Life, Levi Strauss, 3M and Walt Disney. Jimmy Carter is one of its alumni.

Fighting Indian Genocide

As part of a joint session of the Review Commission and the Forum on Indian Genocide and the Planned Extinction of the Family Farm, Bill Means of the American Indian Movement presented a history of the treaties and struggles by Native Americans since the 1820’s. In particular he emphasized the history of the Lakota Nation. Originally bordered by the Wisconsin Delta on the east, the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming in the west, on the south by the Republican River of Kansas, and extending into southern Canada on the north, the Lakota Nation was gradually whittled away over fifty years by various wars and treaties. In 1868, the Fort Laramie Treaty was signed, which gave the Lakota an area of land in South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska for eternity. But much of this land was taken from them in 1877 when gold was discovered in the Black Hills (see box). “The Black Hills of South Dakota represent to our nation what Jerusalem represents to the religions of the Middle East,” Means explained. He went on to ask if Catholics would consider selling the Vatican.

The Black Hills contain about 8 million tons of usable uranium. They are by no means the only Indian lands coveted by energy multinationals. Fully two-thirds of the U.S. uranium reserves and one-third of the low sulphur coal reserves needed for fuel production under President Carter’s energy development plans lie on Indian lands. Uranium mining, near and on Native American reservations, has been correlated with serious health problems. A report presented by Women of All Red Nations (WARN)2 documented radioactive contamination of surface and ground water on the Pine Ridge Reservation. This reservation was the site of extensive uranium mining and milling from the 1940’s through the 1970’s. This study reports increased incidences of cancer on the reservation. Reports presented by other Native American groups outlined similar problems in other regions. What the Gathering hoped to accomplish, as one of its top priorities, was to guarantee that Indian people will not fight alone against this genocide.

Appropriate Technology, Health and Education

Appropriate Technology/Land Self-Sufficiency was a collection of practical and informative workshops on as many different energy and ecologically sound devices, processes and philosophies as one could possibly imagine. The workshop on distilling alcohol for fuel covered the process from start to finish, simply and comprehensively. Other workshops presented information on solar cookers, french intensive gardening and bio-mass methane generation; others dealt with the social implications of appropriate technology and energy planning. Solar-heated showers and photovoltaic-powered public address systems and radios were used to meet the needs of the Gathering.

Health for Survival divided its work into four areas: radiation and chemical contamination; women’s health; holistic health; and midwifery. Each was a cornucopia of workshops on topics such as the nuclear fuel cycle, subtle body healing, low level radiation, and massage. The midwifery classes were three days of intensive study aimed toward teaching the skills needed to assist in birthing.

Education for Survival concerned itself with teaching children the skills needed for survival and with giving educators the materials and background to carry out this work.

Declarations

What comes of a mix of thousands of activists, with nine days of workshops, seminars, jet aircraft, dust and scorching sun? That is a hard question to answer. Certainly not all of the results of the Gathering have been realized or are as tangible as the two specific statements that were drafted.

The Declaration of Dependence on the Land was drafted by the Forum on Indian Genocide and the Planned Extinction of the Family Farm. It concluded:

We are people of the land. We believe that the land is not to be owned but to be shared. We believe that we are the guardians of the land. The future of our children, and of all generations to come, will depend on our efforts today to prevent corporate seizure and abuse of the land. We challenge our concerned sisters and brothers throughout the world to unite with us in the struggle to liberate the land and all people from the economic and political domination of the transnational corporations and the governments that serve them.

Perhaps this view, which was the basis for the Gathering, was best summarized by Marvin Kammerer, the rancher who donated his land for the event, “If I live to be 100, I will never own the land. The land owns me.”

The second statement, the Declaration of Non-Indian People’s Defense of Indian Sovereignty, recognizes the rights of American Indians to the lands ceded to them by the Treaty of 1868. It warns that our “survival demands that we understand the solidarity with native cultures is necessary before we can produce any real change.”

Plans for Action

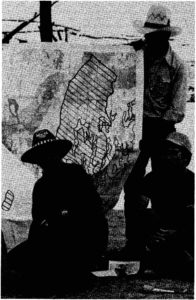

Plans for action were developed at regional and international workshops held on the next-to-the-last day of the Gathering. The workshops addressed the need to develop strategies for survival adapted to the problems encountered in each region. People came away from the Gathering with a new appreciation of the importance of building a united front of opposition to all threats to human survival.

While some regions represented urban areas and others rural areas, each committee agreed that we are all dependent on the land. The direct threats in our neighborhoods and regions differ from one state to the next, but common ground was found by recognizing that without a healthy land base to grow food, support wildlife, retain religious heritage, and provide outdoor recreation, none of us can survive. This is best summarized by the slogan from southern Minnesota, “If you kill our farms, our cities will die.”

Most people in the workshops agreed — whether from the city or the country — that getting the information into the hands of the public was an important problem. Some suggestions on how to solve this problem were: I) establish community newsletters and encourage others to do the same; 2) establish phone trees and other direct, local communication systems; 3) contact all potentially concerned organizations: including labor unions, food coops, schools, religious groups, 4-H clubs, environmental groups, civic clubs, and more; 4) involve the established media by writing letters to the editor, issuing press releases, and holding press conferences; 5) establish information centers and hold regional gatherings; 6) get involved in Parent-Teacher Associations in order to provide our children with a more realistic education. There are more ways for people to network and communicate in their regions. These are just a few of the most general strategies.

There were many suggestions for direct action that can be taken right away. Many areas of the country, including the Black Hills, Harrisburg, and southwestern Minnesota have taken corporations, utilities, and state agencies into court, hoping to force recognition of environmental and health concerns. Some communities, especially large cities, have been holding mass demonstrations and rallies to draw attention to issues and educate those around them. Other people including Indians in the Southwest, farmers in the Midwest, and urban people in the Northeast, have been using civil disobedience, both to prevent destructive actions (such as mining and powerline and power plant construction) and to alert their communities to the dangers. Still other groups are pushing for nuclear moratoriums in their counties and states.

And finally, participants recognized the importance of Indian treaties and Native American sovereignty. There was a commitment from all regions to raise awareness of Indian people’s needs and history, and the current importance of violated treaties.

Energy Development and Native American Land

The U.S. comprises 8% of the world’s population yet consumes 40% of its natural resources. This country has depended largely on foreign nations for energy sources, especially the Middle East. Now with increased nationalization of mining and oil production in Third World countries, the U.S. corporations are coming back to North America because it offers the most politically receptive setting for energy resource exploitation. The United States now leads the world in uranium export; much of it, along with other energy sources, is sold to Third World countries, the so-called “export zones”.

Corporations such as Kerr-McKee, Union Carbide, Rockwell, Gulf, and Exxon are operating or planning uranium mining and milling in the West and Southwest, including the Black Hills. The federal government is also involved in uranium development: for example the Tennessee Valley Authority is involved in all stages of uranium processing and nuclear power generation. Private companies are aided in their explorations by the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Uranium Resources Evaluation Program and several satellites of NASA.

Uranium was first mined in southwestern counties of South Dakota in the 1950’s, then discontinued as government price supports were withdrawn and the price fell to $6 per pound. When the price rose to $40 per pound (down now to $30 per pound), uranium mining became profitable again, for use in power plants and weapons.

One hundred percent of all federally controlled uranium production comes from Indian reservations. One third of the U.S. coal reserves are also on Indian lands. If U.S. Indian nations were considered one nation, it would be the fifth largest producer of uranium in the world; U.S. and Canadian Indian uranium resources added together would comprise the third or fourth largest producer worldwide. The world’s largest uranium strip mine is on the Laguna Pueblo reservation; it has been operated for 25 years by Anaconda, a fully owned subsidiary of Arco Oil Company. Exploitation of other energy resources including coal and oil and related operations such as coal slurry pipelines, high-voltage powerline transmission, and coal gasification processing — some in operation and some in development stages — affect Native Americans in crucial ways.

In some areas, uranium mining is a major employer of Native Americans. One out of five workers on Laguna Pueblo is employed at the mine. On the Spokane reservation in Washington State, one out of four laborers is employed by a uranium mine. The 7 million acre resource-rich Navajo nation, located at Four Corners, where Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona meet, is a prime source of energy for the U.S. The Dine Navajo are the largest Native American population in the U.S. Until the 1970’s, Kerr-McGee, a major uranium producer operated a number of uranium mines and a uranium mill in the Navajo nation.

The people who most directly feel the effects of uranium development are the miners and other uranium processing workers. The most serious health hazard is exposure to radioactivity. Radon gas, released when uranium is mined and processed, breaks down into highly radioactive elements which cause lung cancer and leukemia. Radon gas, which also spreads to people in areas near mining sites, is inhaled by mine workers in very high concentrations. The lung cancer rate for uranium miners is four times higher than the rate for the general population. As of 1978, 25 of 100 Navajos employed at the mines had died of and 20 more were ill with uranium-induced lung cancer. Although uranium mining brings relatively high-paying jobs, the miners become victims of corporate quest for profits.

In 1975, 25 tribal chairpersons of western Indian reservations, supported by an organizational structure of economic and technical advisors from the U.S. and other countries, formed the Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT). Most of the CERT-represented reservations have been the site of active energy development for over 50 years, primarily oil, and more recently uranium. CERT recently received some Federal money to study and implement energy resource development projects for the joint benefit of Native Americans, corporations and the government.

Indian energy resources have always been appropriated with ease. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of Interior approved leases which gave corporations coal for 15 cents a ton when the market price was $20 a ton. Uranium royalties for Indians have been 60 cents a pound when the market value increased from $15 to $50 per pound. These agreements were designed to be in effect for “as long as the ore is producing in payable quantities.” This situation has exploited tribes and their land. The aim of CERT is to get Native Americans a fair price for the resources from their lands, and to make sure that these resources are developed with the environmental and cultural needs of the tribes in mind.

So far only a few of the Native American resource leases have been negotiated. The tribal chairperson of CERT does not always represent the interests of all their people. For example, the Navaho chairperson, Peter MacDonald, who along with LaDonna Harris is one of the leaders of CERT, at first supported development of a coal gasification project on Navajo land, citing the jobs and revenue it would bring. However, many Navajos opposed the project because of the environmental and social hazards it would present, and got MacDonald to withdraw his support of the project. CERT has been criticized for not including poor and traditional people in its meetings and organization; therefore some groups feel it does not represent them.

Nuclear Weapons and the People of the Southwest

People at the Survival Gathering could not fail to consider the encroachment of the military on their lives. B-52 bombers from the Ellsworth Air Force Base were rumbling overhead as they met. Ellsworth houses 150 Minutemen and 11 ICBM’s (each carries 1.5 megaton nuclear warheads), as well as thirty strategic bombers.

The trend in the nuclear arms race for both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. is toward “counterforce” weapons, weapons specifically designed to attack the nuclear forces of the opposing side. The Pentagon estimates that over 300 nuclear bombs might be set off at Ellsworth during a first strike counterforce attack. The ability to attack nuclear forces, as well as cities and conventional forces, has made nuclear war appear less suicidal in some people’s opinion. This attitude greatly increases the chance of nuclear attack, either by design or by accident.

For the people living in Nevada and Utah, there is a new nuclear weapons threat to contend with. Construction of the MX missile system, designed to have missiles moving from silo to silo, is slated to begin soon. The U.S. Defense Department is willing to sacrifice the land and its inhabitants to the cause of their nuclear “shell game”. And if nuclear war should occur, an Air Force general once described the MX deployment area as a giant nuclear “sponge”.

The MX will require 10,000 miles of extra-strong roadway, 2,000 miles of special railroad, 4,600 missile shelters, two missile assembly complexes, at least one military base, and numerous support centers and security alert sites. The environmental impact of this system would be devastating.

The energy and nonrenewable resources required for the MX project are staggering. The Air Force states that the demand for electricity “may require development of local or imported sources such as oil, gas, coal, uranium, and geothermal waters”, and “it is the Air Force’s intention to permit mining exploration and exploitation to the maximum extent possible … “. The government is planning to build the world’s largest nuclear power plant in Nevada for MX related consumption. The plant would need huge amounts of precious water for cooling, and it would present all the risks associated with any nuclear power facility.

The Air Force estimates that during the MX construction period elevated water demands will arise from population increases, cement requirements and dust suppression. The MX will use about 12% of Nevada’s and Utah’s scarce water supplies during construction, and comparable amounts when in operation. Legally, Indian water rights take precedence over all other water rights; the Air Force plans to negotiate these rights with the particular affected tribe. Jerry Millett, chairperson of the Duckwater Shoshone reservation, says, “The Duckwater tribe’s water is not a negotiable or compensable item.”

At least seven bands of Southern Paiute in Utah and seven bands of the Western Shoshone Nation in Nevada would be directly impacted by the proposed MX. Construction of the MX will destroy tribal grazing lands, hunting areas, food, and medicinal-plant-gathering sites. Water, already a scarce commodity, would be depleted. Many native people would be displaced.

The Indian Claims Commission has awarded the Western Shoshone people $26 million for 24 million acres of aboriginal land allegedly taken in 1872 by white settlers in Shoshone territory. However, Western Shoshones are fighting the ICC proceedings and trying to secure a land title based on the claim that their treaty rights were never extinguished. It was revealed recently that negotiations had been in progress between the Western Shoshone and the Dept. of Interior which would have secured about half of the original Great Basin landbase as a permanent Shoshone reservation. Early in 1979, however, the Dept. of Interior suddenly cut off negotiations, and shortly thereafter the President revealed government plans to construct the MX system in the Great Basin.

John Redhouse, of the American Indian Environmental Council observed, “It is ironic that the U.S. government is violating a treaty with one nation (Shoshone) to secure passage of a treaty with another nation (Soviet Union)”.

| HISTORY OF NATIVE AMERICAN TREATIES

The stakes in the Paha Sapa go well beyond $122 million. The plans for industrializing the Black Hills region are staggering. They include a gigantic energy park featuring more than a score of 10,000 megawatt coal-fired plants, a dozen nuclear reactors, huge coal slurry pipelines designed to use millions of gallons of water to move crushed coal thousands of miles and at least 14 major uranium mines. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty will be a valuable ally to those who want to prevent further uranium mining in the Black Hills. Unlike the battles which forced Indians out of their ancestral lands a century ago, this one is no longer being fought alone. The significance of the Black Hills Alliance — and the issues which generated it — lies in its bridging the gap between Indians and whites, between Americans and the rest of the world, between the menace of land expropriation and the more general dangers posed by hasty exploitation of the land’s resources. In that sense, the effort to preserve Native American culture has much broader repercussions, and its import may eventually close divisions between the Indians themselves. “The destruction of the Hills would constitute a direct assault on the spirit of everything native culture stands for,” said Winona Laduke. “Ths really is the last battle.” Just over 100 years ago, an expedition led by General George Armstrong Custer publicized the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, setting the stage for the 19th century struggle for control of Native American land. The more recent discovery of uranium deposits gives Indian land claims momentous new importance. The continuing Native American conflict with modern technology and resource development ties in with a world-wide movement. As Madonna Thunderhawk, an organizer of the Gathering points out, ” … (We) … want people to focus on the issue of survival in general. It won’t do us any good to have the Paha Sapa if the rest of the planet falls to pieces.” The current struggle centers around renewed efforts by the Lakota Nation to recover treaty lands illegally seized by the federal government in 1877. According to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, the Hills were guaranteed in perpetuity to the Lakota Nation. Article XII of the treaty states that no agreement by the Lakota to give up any of their reserved lands “shall be of any validity or force” unless it is signed by at least three fourths of all adult male Indians occupying or interested in the same.” But, in 1877, shortly after Custer’s Last Stand, Congress passed an act which transferred the Black Hills to the federal government without Indian consent. No compensation was offered at the time. On June 30, 1980, 59 years after United States vs. the Sioux Nation entered the courts, the Supreme Court ruled that the Black Hills region had been illegally taken from the Lakota Nation by the 1877 Congressional Act. The Court also ruled that the government owed the Lakota Nation $122 million, representing a purchase price of $17 million (the official estimate for the 1877 worth of the land) plus 103 years of interest. There is no real unity among the Lakota on whether or not to accept the federal payment. Some traditionalists, opposing arrangements to allow uranium mining in the sacred lands, have joined young activists in protesting industrialization of the Hills. Others are not completely opposed to mining, but feel they can get a better deal. After 10 percent is deducted for lawyers, it is estimated that each Lakota would receive between $300 and $2000. As Wally Feather, a Black Hills Alliance organizer, points out: “The government is already cutting way back on subsidy and employment programs on which the reservations have been dependent. They obviously mean to make it real hard on people and to try to substitute this payoff for the regular programs. It’s a strong blackmail but I don’t think it will work.” Indeed, a strong movement has developed among the Lakota to reject the offer of payment outright and, instead, to use the decision as official confirmation that title to the Hills remains with its original owners. “The U.S. government has determined that the Sioux Nation does own the Black Hills, says Reginald Cedar Face. I think we all agree that the Black Hills are not for sale.” Within 10 days of the Supreme Court decision, the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council asked the Court to declare a mistrial. According to Tribal attorney Mario Gonzalez, the Washington-based lawyers who brought the case to the Supreme Court had no contract with the Lakota Nation and were acting illegally. A second lawsuit has been filed, asking $11 billion in damages to compensate for the suffering endured by the Lakota due to the loss of the Hills and for the vast mineral and other resources taken from them in the last 103 years. The suit also asks for the return of federally held land and a halt to all mining in the area. |

The Work of the Gathering Is Now Beginning

After 10 days at the Gathering, people felt a great deal had been accomplished; they had shared impressive amounts of information, formed and strengthened alliances and reaffirmed their commitment to the common struggle for survival. As Black Hill Alliance activist Evelyn Lifskey remarked, “The Gathering is over; the work is just beginning.”

For further information on the following topics contact:

NUCLEAR WEAPONS

Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies

251 Harvard St.

Brookline, MA 02146

National Action Research on the Military-Industrial Complex

1501 Chefry St.

Philadelphia, PA 19102

JOBS AND ENERGY

Environmentalists for Full Employment

1536 16th N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036

Miners for Safe Energy

Box 247

Leads, S.D. 57754

URANIUM MINING AND NATIVE LANDS

Black Hills Alliance and WARN

P.O. Box 2508

Rapid City, S.D. 57709

American Indian Environmental Center

P.O. Box 2508

Rapid City, S.D. 57709

International Treaty Council

777 United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017