This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Fight for Safe Workplace: Epoxy Boycott in Denmark

by Janine Morgall

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 5, September-October 1980, p. 23-26

Janine Morgall is a member of Aktionsgruppen Arbejdene Akademikene (Action Group: Works-Academics) in Copenhagen, Denmark. The group was active in the epoxy boycott and continues to be active in health and safety problems in the work environment.

In June 1978 at a meeting of Byggefagenes Samvirke (BS), a federation of construction workers’ unions, the results of a research project from The Royal Danish School of Pharmacy were made public 1. The report concluded that aromatic epoxy resins (used extensively in the building and ship building industry) correlate highly with carcinomas. Experience at the workplace also identified epoxy as the cause of eczema and allergies.

On the basis of this report BS advised its members to boycott on the job all products containing epoxy resins. Workers went out on strike. The Minister of Labor was asked to take epoxy products off the market, and there was a call for a registration and screening system for all new chemicals coming out on the market.

The boycott received support from the local unions but not from the national union, which felt that the government regulations were sufficient. It considered the boycott too militant and felt the problems should be resolved in a more cooperative manner. Nonetheless, for over a year workers at a county-owned sewage treatment plant (which was under construction) successfully boycotted epoxy products. During the last three months a physical blockade was formed. The blockade was eventually removed by police force.

Although the Danish Labour Inspection Service set up government regulations limiting the use of epoxy, over 30 dispensations were granted to industry (mainly on economic grounds). As a result workers who refuse to work with epoxy products have breached their collective bargaining contract and are subject to a fine by the industrial tribune.

Epoxy: Help or Hazard

Epoxy resins were first synthesized in the 1930s and are the most important of the epoxy compounds. Epoxy consists of two parts — a resin and a hardener — which are mixed together shortly before use. Epoxy resins have many uses and functions: as surface coatings and adhesives, especially for metals, and as a component of paints, lacquers, and glues. They are used in more than 16 thousand different products. Used extensively since the mid-1950s as surface coatings, they have been acclaimed because of their ability to produce a smooth and resistant surface. Dissolved in paints, they are used to seal off and smooth out cement surfaces in buildings. They are used to repair cracks in cement, to prevent corrosion of metal and the cement surrounding it, and in the production of many of the products we buy for our homes. In Denmark they are used primarily in the building industry, including ship building.

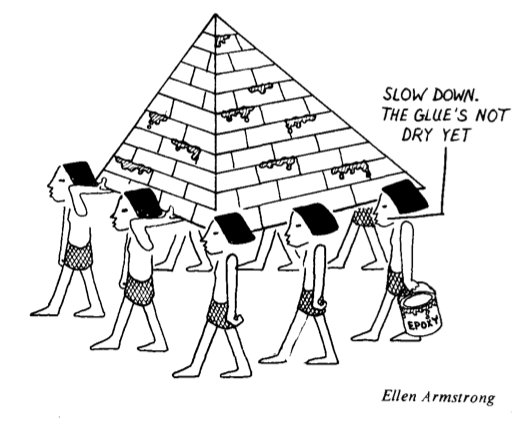

Besides being so versatile, epoxy resins are very effective. Some people claim that there are no adequate substitutes for them. They have a low degree of shrinkage, are highly adhesive and have an almost unlimited shelf-life. Epoxy was used in Egypt to glue the pyramids together when they were moved.

The economic advantages of epoxy resins are illustrated by the following two examples. The foreman of the Master Builder’s Association in Denmark told a news reporter that if he had to put 100,000 square meters of tile and he could not use any epoxy products, it would cost approximately 30-40 million kroner (about 6-7 million dollars) in repairs because the tiles would keep falling down. Similarly, the maintenance of a water tank protected by epoxy need only be done every 15 years, whereas a water tank not protected by epoxy requires maintenance once every three years. Versatility, effectiveness, and good economics — three good reasons for using epoxy. There seems to be only one reason to support the boycott of these products — they are a health hazard.

Unfortunately, the resins are extremely irritating, and contact with fumes of the epoxy resins has caused dermatitis of the face, eyelids, and neck. Inhalation of vapors or aerosols can lead to acute pulmonary edema, or fluid in the lungs. The reported incidence of dermatitis among those having prolonged or unusual contact runs from 10 to 60 percent. Sensitization is not uncommon and may run as high as 2 percent of the exposed population. 2

Then there is the research done at the Royal Danish School of Pharmacy which used the “Ames Test” (see box) and concludes:

To prevent cancer and genetic damage in humans it is necessary to minimize the exposure to substances such as aromatic epoxy resins which have been shown to be mutagenic in bacteria, and thus must be considered as potential mutagens and carcinogens in human beings. 3

These results were supported, almost two years later, by a study that appeared in Cancer Research 4 which concluded that epoxy resins were carcinogenic in mice skin.

THE AMES TESTThe Ames Test, developed by Professor Bruce Ames and his colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, is a fast inexpensive way to screen for potentially carcinogenic (cancer-causing) chemicals. The test does not directly examine the ability of chemicals to cause cancer in animals, but rather it examines the ability of chemicals to mutate (cause change in) the DNA of bacteria. The test has demonstrated that 90% of the chemicals known to be carcinogenic in animals are also mutagenic in bacteria, suggesting that any chemical which is positive in the Ames Test is possibly a carcinogen. The test uses strains of bacteria which are unable to grow unless they are supplied with the amino acid histidine. When the chemical being studied and the bacteria are placed together on solid growth medium without histidine, none of the bacteria can grow unless the chemical is a mutagen. If it is, a few bacteria will mutate so that they will be able to make their own histidine, and grow on the plate. The World Health Organization estimates that environmental factors, including chemicals, are responsible for 75-85% of all cancers. A thorough animal test of a single chemical costs over $100,000 and takes 1-3 years. Not enough scientists and facilities exist to perform animal tests on the over 60,000 chemicals now in use, much less the almost 100 new ones introduced each year. Moreover, the few chemicals that are carcinogenic are usually not discovered until many people have been exposed to them. The Ames Test takes only a few days and costs less than $1000 per chemical, which makes it possible to test more chemicals in less time, and screen chemicals before they are introduced. |

The Unions Respond

In recent years labor unions have become more and more interested in problems in the work environment. In Denmark unions have initiated research into social and medical problems related to work. Their goal has been to make the workplace safe for their members and to track down work-related health hazards and illness. There are over 10,000 uncontrolled chemical products on the Danish market. Epoxy has been singled out as one of these chemicals which is known to cause health problems and which now is suspected of being carcinogenic.

Besides wanting epoxy products banned in Denmark the epoxy campaign had other goals. One was to develop a system independent of the employer and the manufacturer whereby all chemicals would be tested and approved before they came out on the market. A long-range goal was to demonstrate the need for changing the law regarding toxic substances to insure an effective screening of all chemicals before they come out on the market. Another concern of the unions was the laws forbidding persons with tendencies toward eczema and allergies from working with epoxy products. Intended to protect the workers, in fact these regulations cut 10-15 percent of them off from their profession. This sorts out the work force rather than the chemicals. It also gives employers grounds for firing anyone with tendencies towards eczema or asthma. The result is two labor markets, one for the healthy and one for the unhealthy.

Lastly the unions questioned a system which makes workers choose between consideration for their health and consideration for their employment! Should the ability to compete on the labor market be based on more or less unhealthy working conditions?

The Workers

It is estimated by the National Trades Unions Organization (LO) and the Employer’s Confederation (Dansk Arbejdsgiverforening) that 15,000 Danish workers come into daily contact with epoxy and that due to the versatility and effectiveness of epoxy resins that number is rising every day.

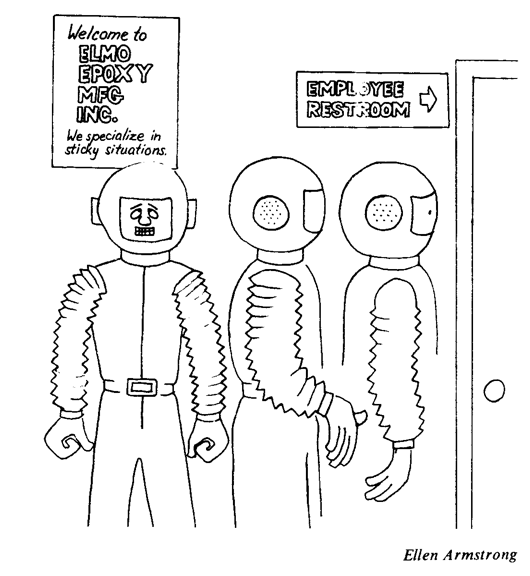

In their statements to the media, workers have been clear that they want dangerous and harmful chemicals banned. They do not agree that it is just a question of more and more protection. Some substances are so harmful (epoxy is one of them) that they are forced to wear what resembles a “space suit” in order to be properly protected. These suits are uncomfortable and cut down the worker’s productivity. Several studies have shown that these suits still do not protect them from dangerous vapors. Workers who must wear special suits are tired of the creams, gloves and masks they are forced to wear. They want to be able to dress like normal construction workers, in normal work clothes.

The Employers

Many employers expressed bewilderment over the epoxy boycott. One told the newspapers that epoxy products had been used for years and that it was only recently that this claim about epoxy being carcinogenic had come up and that he simply did not know what to do about the situation.

An engineer at Lynetten, a county-owned sewage treatment plant, says that officially they must hold themselves to what the Ministry of Labour says but that in reality they can’t force the workers to work with epoxy. When all is said and done, the problem will be left with the entrepreneurs, many of whom work exclusively with epoxy products.

There is of course a very real economic threat. Many claim that there are no substitutes for epoxy when it comes to efficiency and economy. If Denmark were to ban epoxy products it would be the only country in the world to do so; this means that Danish companies could not, quality-wise or economically, compete on the world market. Some claim that were there restrictions against epoxy products it would cause big economic problems and most likely add to the already high rate of unemployment.

The Danish Labour Inspection Services (Arbejdstilsynet)

When the campaign to boycott epoxy began, the Danish Labor Inspection Services told newspapers that they did not doubt that the Ames test was positive for the three epoxy resins tested. They also agreed that the Ames test was the best short-term test available for the screening of possible carcinogens. However, they did not agree with the interpretation of the results by the research group from the Royal Danish School of Pharmacy, and they did not ban epoxy from the market. A representative is quoted in a report from the School of Pharmacy as saying:

Epoxy is a dangerous substance which should be treated with respect, but there are no reasonable grounds to introduce a general ban of epoxy products due to the results of this report. (authors translation)

The Danish Labour Inspection Service issued a pamphlet containing guidelines, agreed to by the National Labour Organization and the Danish Employer’s Confederation, for protecting workers when they work with epoxy products. In October 1978 they also issued government regulations with rules for limiting the use of epoxy. The government regulations did not ban epoxy; instead they contained stricter rules which can be outlined as follows:

(1) Epoxy suppliers must be registered with the Labour Inspection Service who will then give their approval that the material may be used and that the ingredients and instructions are acceptable. The Labour Inspection Service’s approval is based solely on information from the supplier.

(2) Epoxy may be used only if another, less dangerous, product has been tested and gives unsatisfactory results. It is the employer who decides to what extent another material is unsatisfactory.

(3) Spraying epoxy outside of closed system, i.e. cabin or box used for spraying, is forbidden.

(4) Workers must wear protective clothing, gloves, etc. to avoid epoxy contacting the skin.

(5) Workers with allergies or very sweaty hands are forbidden to work with epoxy.

(6) Workers who work with epoxy must complete a special course on precautionary measures for working with epoxy.

(7) The workplace must have adequate washing facilities. These facilities must be placed so that other workers do not come in contact with epoxy. 5

The Danish Labour Inspections Service, the National Labour Organization and the Employer’s Confederation have agreed that the health and safety of workers using epoxy are not in danger so long as the government regulations are observed. Legally this means that a worker cannot refuse to work with epoxy by claiming that it is a threat to “life, honor and welfare.” It is a breach of collective bargaining for a worker to refuse to work with epoxy if an employer follows the government regulations.

This situation raises many questions: Do the government regulations protect workers against allergies and the risk of cancer? How can we be sure? Are there any guarantees that nothing will happen?

Despite the government regulations, B.S. continued its boycott of epoxy. It argued that in practice skin contact cannot be avoided when working with epoxy. Furthermore, B.S. maintained it was degrading and stressfull for its members to work with material that require them to be dressed like astronauts in order to be safe. At Lynnetten workers hindered the use of epoxy for over a year. B.S. held a large solidarity march outside the workplace in which 5,000 construction workers participated. In the last two to three months of the boycott, trade union leaders and union members formed a physical blockade to keep out the boycott-breakers. The blockade was eventually removed by the use of police force, and the boycott was called off.

AKTIONSGRUPPENARBEJDEREAKADEMIKENEThe goal of Aktionsgruppen Arbejdere Akademikere (Action Group: Workers-Academics) is to support trade union and workplace activities that deal with health and safety problems in the work environment. This is achieved by disseminating knowledge and establishing contacts among workers, safety representatives and trade unionists, as well as by developing advice and counseling services. A basic principle of Aktionsgruppen is that the workers decide how these resources are used. Aktionsgruppen issues pamphlets on different topics relevant to the work environment such as Danish laws on the work environment, industrial health services and workers compensation. These pamphlets are meant as discussion papers and aides to debate. They are therefore written in a form which makes them adaptable as background material for courses, professional conferences, study groups and meetings. Members of Aktionsgruppen include: workers, safety representatives, trade unionists, doctors, engineers, nurses, sociologists, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and pharmacists. There are also 20 trade unions and 20 clubs that have joined. Aktionsgruppen was active in the epoxy boycott and continues to be involved in health and safety problems in the work environment. Anyone interested in working in agreement with Aktionsgruppen’s goals can become a member. Contact Address: Benny Christensen Arnesvej 44 2700 Bronoshoj DENMARK |

The Government Regulations — One Year Later

The government regulations have been in force for over a year. What are the effects?

First of all, no studies have been done to determine the extent to which the regulations have protected the workers in practice or even how many employers actually followed the regulations. More than 2,000 epoxy products have been reported to the Danish Labour Inspection Service, and 600 have been approved.

With regard to the rule forbidding spraying of epoxy outside of a closed system — 30 dispensations have been granted. The entire ship building industry has been given dispensation. To get dispensation a firm approaches the Danish Labor Inspection Service (Arbejdstilsynet) which then consults the National Trades Unions Organization (L.O.) and the Employer’s Confederation (Dansk Arbejdsgiverforening). If there is agreement between these two, dispensation is granted. It is the impression of the workers that L.O. has consistantly prioritized the workplace higher than the working environment.

There are still no standards to define what appropriate protective equipment is nor has there been any systematic checks on work sites to determine whether the protective equipment being used is sufficient.

No action has been taken to help workers who are allergic to epoxy (and are “protected” by the regulations) to find other work. There is now a special course on precautionary measures for working with epoxy, which consists of 16 hours of instruction in the use of epoxy. The course is based on the assumption that if used properly epoxy is not at all dangerous. Many feel that the course is run like a “sales promotion” and ignores the basic and fundamental danger of this product.

Conclusion

Epoxy products have not been banned from the Danish market. In response to the government regulations issued in 1978 restricting the use of epoxy products, many firms have applied for and received dispensations. This means that workers who refuse to work with epoxy products can be brought before the industrial tribune. There have been cases of this and workers have been fined as a result.

Despite the fact that B.S. was forced to call off its boycott, due to intervention by the Danish police, the action has had far-reaching consequences. It has shown the various methods which are necessary in order for workers to protect their own health. It has made the public aware of the danger of chemicals at the workplace. It has proved that the Danish Labour Inspection Service does not protect the health interests of the workers when it really counts. And finally it has started people thinking: When do considerations of efficiency and economy take precedence over health hazards? Who should decide?

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 5 <<

REFERENCES

Berlingske Tidende, July 1 and 9, Aug. 5, 7 and 8, 1978, Jan. 8, 1979.

B.T., June 9, 1978.

The Economist, Nov. 25, 1978.

Patrick Kinnersly, The Hazards of Work: How to Fight Them, London: Pluto Press, 1973.

Politiken, June 6, 9, 22, 25, and 29, 1978 March 27, 1979.

Solidaritet (Tillaeg Til V.S. Bulletin 188), Special Number: Epoxy Boykotten (The Epoxy Boycott, November 1978).

Weekendavisen, June 30, 1978.

- Andersen, Kiel, Larsen, Larsen and Jette, “Mutagenic Action of Aromatic Epoxy Resins, Nature, vol. 276, Nov. 23, 1978, pp. 391-392.

- Page and Mary-Winn, Bitter Wages: Ralph Nader’s Study Group on Disease and Injury on the Job, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1973.

- Andersen, Kiel, Larsen, Larsen and Jette, “Mutagenic Action of Aromatic Epoxy Resins, Nature, vol. 276, Nov. 23, 1978, pp. 391-392.

- Holland, Gosiee and Williams, Cancer Research, no. 39, March 1979, pp. 1718-1725.

- Lars Iversen, Argument, vol. 1, March 1980.