This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Exporting Toxic Wastes: Dumping for Dollars

by Christopher McLeod

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 5, September-October 1980, p. 27-28

Christopher McLeod is a correspondent for Pacific News Service. He has written on the chemical industry for Mother Jones magazine and other national periodicals. Copyright, 1980 Pacific News Service.

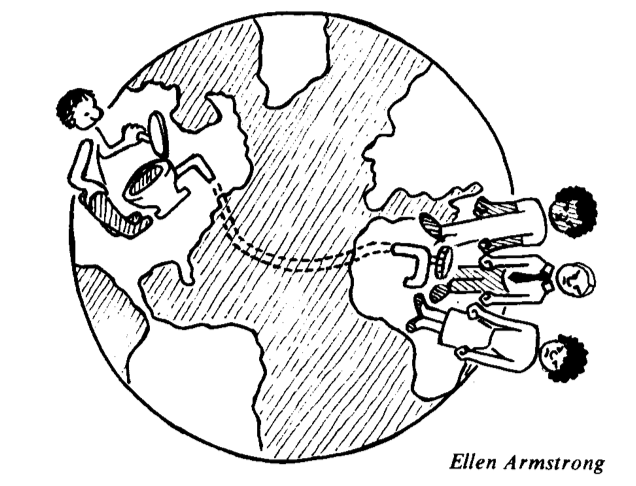

With stiff new federal regulations on the domestic disposal of hazardous wastes scheduled to go into effect this November, an unusual breed of American entrepreneur has begun making the rounds of Third World nations from Africa to the South Pacific.

The business is neither selling nor buying anything. It is finding new dump sites for part of more than 100 billion pounds of toxic chemicals and nuclear wastes discarded annually in the U.S.

The prospect that these materials may wind up abroad has federal officials worried that our toxic wastes will poison U.S. foreign relations along with the environments of developing countries around the globe. But government efforts to prevent their export are being hampered by a rift between the State Department and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) over the way the matter should be handled.

In the last year, American waste disposal companies have approached 11 countries in Africa and Latin America. Philadelphia landfill operator David Ehrlich of the Gloucester Environmental Management Services, says he has only “to work out some technical details” before he will begin shipping chemical wastes from the East Coast of the United States, as well as Europe, to a West African nation which he refuses to name.

But ever since last December, when Washington was notified that chemical industry representatives were offering multi-million dollar deals to Third World leaders in exchange for guaranteed dumping sites, an ad hoc committee of representatives from the State Department, the EPA, and the Council on Environmental Quality has been moving to stop such exports.

A classified State Department cable to Sierra Leone warned that this new export would lead Africans to “condemn the United States for dumping its wastes in the black man’s backyard.” The cable was prompted by a proposal from Nedlog Technology Group of Arcada Co., to ship 1 million tons of toxic chemical wastes to Sierra Leone per year.

When the cable was leaked to the press, the President of Liberia, which borders Sierra Leone, flew to the capital city of Freetown to urge President Shiaka Stevens to reject the American offer, and student demonstrations were organized at Njala University in Freetown, and at the Sierra Leone Embassy in Washington. Eventually, Stevens went on national TV to deny that his government had entered into any agreement to import toxic wastes, but he did not rule out such an agreement in the future.

Dumping for Dollars

Nedlog vice-president James Wolfe, who had tried to set up the waste site in Sierra Leone, predicts that the new EPA regulations on chemical waste disposal will increase the cost of waste disposal, creating a mountain of paperwork and “an incredible logjam” of dangerous chemicals awaiting disposal. “That’s why we were looking overseas to find countries that need foreign exchange and jobs, and have plant sites,” says Wolfe, who has dropped the plan because of the adverse publicity. But, he says, “We’re being a little paternalistic in telling the Africans what they can and can’t do. If I was Sierra Leone I’d be pissed as hell.”

Meanwhile, David Ehrlich is going ahead with plans for a treatment plant and landfill in another west African nation. Though Ehrlich doesn’t know exactly what chemicals he will ship, he says, “There is so much waste out there that I have people coming to me constantly. They’ll be standing in line. We have insufficient waste facilities here, and this stuff has to go somewhere.”

Ehrilich says the wastes will be disposed of in “an environmentally sound manner,” using state-of-the-art technology. “The people I’m dealing with are university-trained. It’s not one of your more backward countries. Technically they know what they’re doing. They have pride in their environment. Maybe even more than we do.”

But a look at the chemical dumping record in the United States casts serious doubt on industry assurances. According to the EPA, 90% of this country’s hazardous chemical wastes have been disposed of in an “environmentally unsound manner.” The EPA has identified 2,000 waste sites in the U.S. which may “pose imminent hazard” to public health and the environment. This year, 100 billion pounds of toxic chemical waste will be generated by American industry, and according to Senator Carl Levin’s Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, a full 65 percent of it will go unregulated under the new regulations.

The EPA and the State Department Disagree

On the issue of exporting the toxic wastes, the split between the EPA and the State Department reflects EPA’s primary concern with the U.S. environment and the State Department’s concern with U.S. foreign relations. Under the terms of the new Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the EPA simply requires the exporter to notify it four weeks prior to shipment of the hazardous waste, so that the EPA can inform the receiving country of the shipment and later verify its arrival. But actually, says an EPA official who asked not to be named, “The EPA’s attitude is one of indifference. They’d like to see the waste go overseas. They’re not going to go very far out of their way to worry about it.”

Back at the State Department, however, policymakers have decided that the notification requirement is inadequate. According to Dr. Jack Blanchard, of the State Department Office of Environment and Health, the State Department will move soon, with the support of the Commerce Department and the Department of Justice, to place any EPA-designated “hazardous chemical waste” onto the “Commodity Control List,” which under the Export Administration Act, gives the executive branch the power to require licensing of exports which might adversely affect U.S. foreign policy. Such licensing will serve to discourage dumping by requiring public hearings on proposed exports, as well as a written State Department opinion on the potential impact on U.S. foreign policy. Says Blanchard, “We anticipate that the situation will come up again in the future, and we want to have a mechanism in place ready to deal with it.”

It’s Getting Worse

It will come up again, and soon. David Ehrlich says he plans to start shipping toxic wastes within the next six months, and if the U.S. government moves to stop him he says he will ship wastes from Europe to the west African dumping site. Meanwhile in New Jersey, the Newark Star Ledger has reported a “still confidential plan” by local interests to establish a hazardous waste dumping site on the western shore of Haiti. And EPA documents reveal that in the last six months, three Texas companies — Diamond Shamrock, Quanex, and the Arbuckle Electrical Machinery Co. — have exported shipments of PCBs (a well-known carcinogen) for disposal in Mexico, South Africa, and the Dominican Republic.

Voices of Protest

The voice of protest from Third World nations is growing. Angry Mexican officials requested a closed door session with U.S. governors at the first international conference of border states in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, this month to discuss dumping. And the UN environmental program adopted a resolution at its annual meeting in Nairobi calling on government to control the international transfer of toxic chemicals and insure adequate measures for handling and disposing of such wastes.

All of this may be simply a prelude to a much bigger controversy over the possible export of nuclear waste materials. Boeing has contracted International Energy Assoc. Ltd. (IEAL) — a Washington, D.C. consultant firm — to do “a very large and elaborate study” entitled “The Pacific Basin Storage Study,” which, according to Daniel Lipman of lEAL, will assess “the potential market” for Boeing to construct facilities for the “storage of spent nuclear fuel in the Pacific region — not just from the United States, but also from Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and the Philippines.” The rationale for storage in the Pacific, says Lipman, is primarily to prevent reprocessing and creation of weapons grade plutonium, and secondly to give Asia’s nuclear reactors an outlet for an ever-growing quantity of spent fuel rods. Potential sites considered in recent years include northern Indonesia, Malasia, Australia, the Marshall Islands, the Caroline Islands, Wake Island, Palymyra, Guam, and possible seabed disposal in the Mariana trench and the Philippines trench.

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 5 <<