This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The Work of Raymond Pearl: From Eugenics to Population Control

by Gar Allen

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 4, July-August 1980, p. 22-28

Gar Allen teaches biology at Washington University in St. Louis. He has been active in the International Committee Against Racism.

Eugenics has been defined as the attempt to use theories of heredity to improve the genetic quality of the human species. During the first three decades of the 20th century, eugenics emerged as a wide-spread scientific and popular movement, both in Europe and the United States. Using the then-newly-discovered concepts of Mendelian heredity, eugenicists sought to show that much of human social behavior was genetically determined. In practical terms, eugenicists wished to restrict the breeding of those individuals they deemed to be socially unfit, and to encourage the breeding of individuals they deemed to be socially fit.

The eugenics movement had a wide-spread influence, particularly in the United States during the early decades of the 20th century, where it provided a quasi-scientific rationale for passage of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, and of sterilization and antimiscegenation laws by over 30 state legislatures between 1907 and 1935. In Germany it led ultimately to the Holocaust with biological and genetic claims for the inferiority, and hence dispensability, of Jewish people.

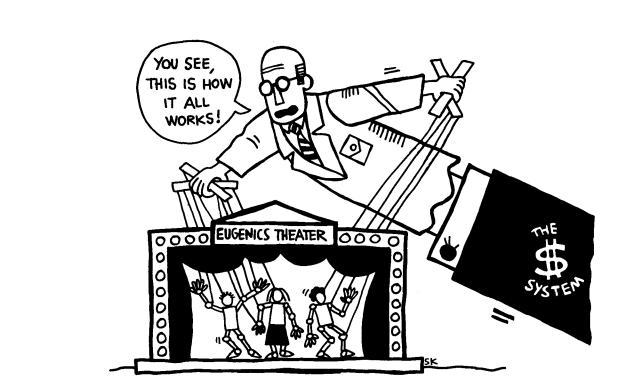

The two currently standard histories of American eugenics suggest that the movement died out by the late 1930s or early 1940s, and that by that time its racist and elitist ideas had fallen into disrepute, especially in the scientific community.1 But this picture of the later history of eugenics is greatly oversimplified, and obscures some of the most basic social processes which have shaped the face, and therefore the uses, of science. In fact the eugenics movement underwent a gradual but significant metamorphosis between 1920 and 1940 — a metamorphosis which, as in insect life cycles, caused the outward structure to appear very different while leaving the inner core largely unchanged. The new eugenic thinking took the form of the population control movement, which began to emerge in the 1920s but attained considerable force only after World War II. Beneath an apparently very different movement and web of goals, was the old eugenic ideology of the wealthy controlling the child-bearing practices of the country’s, or the world’s, poor.

In this article I will discuss the transition from eugenics to population control as it occurred in the work of one man, Raymond Pearl (1879-1940). Pearl is a useful and important figure for several reasons. He was a well-known biologist with a considerable reputation both in the United States and abroad. In the early decades of his career (1910-1925), Pearl was a strong and influential supporter of the eugenics movement. After the mid 1920s, however, he dissociated himself from the movement, severely criticizing its departure from scientific facts. At the same time he became one of the leading spokespersons in the United States on the issue of population growth and “overpopulation.” On the scientific side he became an architect of modern demography and the statistical analysis of population growth; on the political-organizational side he became a national and international leader of various organizations aimed at controlling (i.e., limiting) the growth of the human population. Pearl’s switch from support of eugenics to population control was not random or capricious. His developing ideas show a clear ideological transition: in his mind the social value of each of these movements was the same, a desire to improve society through the use of known biological principles. As his support shifted from eugenics to population control, Pearl’s view of the causes of social problems did not change; what changed was the particular biological form in which he sought an explanation — and a solution.

An early association with Karl Pearson and Frances Galton in London in 1905 and 1906 was undoubtedly responsible for Pearl’s early interests in biometrics and biostatistics on the one hand, and in eugenics on the other. Several of Pearl’s early papers show clearly how the two subjects were closely intertwined in his thinking. In a biometrically-oriented paper of 1905, he emphasizes the correlation between brain weight and race. And in an eugenically-oriented paper in 1908, “Breeding Better Men,” he argued from biometrical data that moral and mental traits are inherited, and can be bred in or out of a population depending upon the selective measures applied.2 He defined eugenics as “the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race, also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage; and it embodies the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations.” To Pearl, eugenic considerations were vital to the future of the human species. Something must be brought into play to replace crude natural selection:

This eugenics aims to do. Its fundamental assertion is that the continued improvement and betterment of the human race, either physically, mentally, or morally, cannot be insured, nor can its degeneration be prevented, solely and entirely by adapting the environment to man. On the contrary, attention must be paid to the fundamental biological makeup of man himself. The unfit, the great body of physical, mental and moral derelicts, must not be allowed to reproduce themselves indiscriminately as they now for the most part are. And further, every legitimate effort possible must be made to encourage the reproduction of the fittest.3

Although Pearl admired social Darwinism, he was of that later generation which could not accept the crudities and harshness of a completely laissez-faire attitude toward the “unfit.” As he wrote in 1908: “Our highly developed human sympathy will no longer allow us to watch the state purify itself by aid of crude natural selection. We see pain and suffering only to relieve it, without inquiry as to the moral character of the sufferer or as to his national or racial value.”4 To Pearl the value of eugenics was that it was based upon science and scientific methods. “Hitherto,” he wrote, “everybody except the scientist had a chance at directing the course of human evolution. In the eugenics movement an earnest attempt is being made to show that science is the only safe guide in respect to the fundamental of social problems.”5 Eugenics was the rationalist approach which would lead human evolution along a positive course.

Pearl believed that both physical and mental or moral traits are largely inherited in human beings. He calculated correlation coefficients between fathers and sons, brothers and sisters, for such characteristics as “temper,” “vivacity,” “assertiveness,” “conscientiousness” and claimed that the correlations were all about .5! Pearl noted: “It might appear at first thought that such characters could not be treated metrically, because no one of them can be measured in the individual with absolute accuracy. But such is far from the case. Developments of higher statistical theory make it possible to treat data of this kind with quantitative precision.”6 Pearl’s statement is curious, for it is obvious that the quantitative measurement of a trait is quite different from the statistical analysis of the measurements of that trait, once taken. No matter what sophisticated statistical techniques are available, nothing enables one to get around the problem of measuring an unmeasurable entity. Pearl’s dodge here represents the same biased view that lies behind the I.Q. argument.

Pearl went on to argue that the way to increase or decrease the presence of specific mental and moral traits in the human population would be through the same avenues as used for physical traits: selective breeding. Thus, he favored the two-pronged approach popular among eugenicists at the time: (1) positive eugenics — encouraging the morally and mentally fittest individuals in society to have more children and (2) negative eugenics — discouraging morally and mentally “degenerate” individuals from having many, or any children. Ultimately, Pearl hoped the government could be persuaded to take this matter seriously and institute corrective procedures and programs on a large scale. He noted with enthusiasm that eugenics “is ‘catching on’ to an extraordinary degree with radical and conservative alike, as something for which the time is quite right. “7

Pearl’s Criticism of Eugenic Principles and the Eugenics Movement

However, by the post-war period Pearl had become aware that eugenics, and its parent science genetics, were drifting further and further apart. When it was proposed that the eugenicists hold their international congress in 1921 co-jointly with the International Genetics Congress, Pearl opposed the move because he thought eugenics as a movement was beginning to lose touch with modern findings in genetics. If eugenics were to serve any function, it was to provide a scientific basis for the rational control of human evolution. To the extent that eugenics got away from rationality (i.e., science) and became more and more of a propagandistic enterprise, Pearl lost sympathy with it. While even in the early days (prior to World War I) eugenic thinking had never been as objective or rational as its proponents claimed, in the post-war period eugenicists made increasingly unfounded claims for the validity and scientific basis of their conclusions.

By 1927 Pearl had lost all patience with standard eugenics. He wrote a scathing attack on eugenics and the eugenics movement in H. L. Mencken’s influential journal, The American Mercury. Titled “The Biology of Superiority,” the article took eugenicists to task for their hasty generalizations and propagandistic tendencies.8 Pearl pointed out that much of modern eugenics is based upon the idea of “ancestral heredity” derived from Galton. Two modern discoveries in genetics, he emphasized, had undercut Galton’s basic notions: Johannsen’s pure line selection experiments with beans, and Mendel’s laws of segregation and random assortment. Both theories emphasized that it is impossible to determine with any certainty the genotype of an organism from an inspection of its phenotype. Like Johannsen’s experiments, those of Mendel show that two organisms that look alike phenotypically may be quite different genotypically. Eugenically speaking, Pearl pointed out, one cannot necessarily obtain superior offspring by breeding phenotypically superior parents. Many individuals who appear healthy and vigorous may actually be carriers of defective (though recessive) genes. The only true way to determine parental genotypes is through experimental breeding. This was exactly what eugenicists could not do. As Pearl pointed out, the only certain guarantee of the worth of any individual for breeding of superior forms is not the superiority of that individual, but the superiority of its progeny. The central fallacy of modern eugenics, according to Pearl, lies in the fact that “like does not produce like.”

To demonstrate his claim that like does not necessarily produce like in human beings, Pearl surveyed a thousand individuals of distinction in the Encyclopedia Brittanica. His criterion for “distinction” was, he claimed, highly objective: having a full-page or more of coverage in the thirteenth edition (1926). Pearl then searched out the parents of these famous individuals to determine to what extent they (the parents) also appeared in the encyclopedia. He observed that the parents of most of the eminent individuals with whom he had started were not even mentioned; in most cases, those that were mentioned received far less space (measured in millimeters), than the original sample. With regard to this parental group, Pearl concluded rather drily: “Some of these parents would have been segregated or sterilized if the recommendations of present day eugenical zealots had been in operation. And I estimate that a good half of these fathers would have been urged to curb their reproductive rate in the interest of the ‘race’ “9

From Eugenics to Population Control

In a paper delivered before the Second International Congress of Eugenics in 1921, Pearl described how he began to relate the quantitative issues of population control to qualitative issues of eugenical breeding. Pearl opened his paper by asking what happens “when a living organism capable of indefinite multiplication of its numbers by reproduction finds itself confined to a universe strictly limited in size?” Pearl put the question to an experimental test with the fruit fly. He placed a pair of flies with 10 to 12 of their offspring into a pint milk bottle and censused the population every three days. He showed that the change in the fly population exhibited a smooth, s-shaped curve. In another paper published a year earlier, Pearl and L. J. Reed had mathematically analyzed a human population growth curve and found it to be essentially the same. To Pearl the implications of this were profound:

It is evident enough that since the same mathematical theory which described the growth in experimental Drosophila [fruit fly] populations also described that of human populations, it is in the highest degree probable… that human populations in limited areas grow in essentially the same manner as experimental population in closed universes. In other words, population growth in respect of its rate appears to be a fundamental biological phenomenon in which insects and men behave in similar manner.10

Pearl felt that he had discovered a biological law regarding growth of organisms. He attempted to strengthen his argument even more by claiming that the curve for population growth followed the same pattern as a curve for the growth of individual organisms from egg to mature adult.

To Pearl there were important implications of discovering a regular law of population growth. The ability to describe population growth of many different organisms by the same mathematics suggested an identical and underlying biological cause. Furthermore, if human population growth was indeed subject to the same laws as fruit flies, then it was possible to predict with some accuracy the demographic future of the human species. Using the regular curves of population growth, Pearl extrapolated to the point in time at which any given geographical region of the earth would be saturated with human beings. Thus, he concluded, the planet could not go on indefinitely supporting more and more people. How, Pearl asked, was the problem to be solved? The answer was simple: by limiting reproduction. There were three basic methods of achieving this goal: (1) by operative interference (such as sterilization), (2) by segregation of the sexes, or (3) by “birth control,” meaning contraception. To Pearl it was the latter which offered the most hope from both a practical and an ethical (or religious) point of view.

But birth control per se was not enough of an answer, Pearl argued. Birth rate deals only with quantitative, and ignores the more important qualitative, changes that occur when population growth occurs unchecked. Pearl was particularly concerned with the question of differential fertility:

Projecting our thought ahead a moment to that time, at most a few centuries ahead, we perceive that the important question will then be: what kind of people are they to be who will then inherit the earth? Here enters the eugenics phase of the problem. Man, in theory at least, has it now completely in his power to determine what kind of people will make up the earth’s population at saturation.11

In Pearl’s view all available evidence suggested that the lower socio-economic groups were greatly out-reproducing the higher. The spectre of “race suicide” was raising its head. Between 1915 and 1925 a number of eugenicists had pointed out that positive eugenics (encouraging the superior stocks of the human species to have more children) had been a notorious failure. The movement had thus been left with only negative eugenics as a means of reducing the supposedly disastrous consequences of high birth rates among the poor and socially defective classes. Negative eugenics — i.e., sterilization, contraception, etc. — lead directly to the concept of birth control.

Thus, Pearl’s interest in the population control movement arose out of his conviction that (1) the orthodox eugenics movement had floundered on subjective and prejudicial science, and (2) positive eugenics was simply not working. Population “control” really meant population selection. According to Pearl, birth rates of those people deemed to be biologically degenerate, or defective, would be the targets for social action. As Allan Chase has succinctly put it, in the early decades of the century the programs for birth and population control were aimed directly at the gonads of the poor.12 Population control was little more than eugenical thinking applied on a global scale.

Pearl and Population Control: Ideology and Institutionalization

Raymond Pearl did not, of course, invent the population problem, nor was he the only one to evince an interest in it in the 1920s and 1930s. Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) brought the issue into focus most explicitly in the late eighteenth century, and has been quoted ever since as the major scientific ideologue of population control. Pearl was a great admirer of Malthus, claiming that the latter’s Essay on Population was “one of the greatest books the human mind had produced, so far ahead of its time that in the main his argument is truer and more significant today than it was when he wrote it.”13 And, to many of Pearl’s biological friends, such as E.M. East and W.E. Castle at Harvard, the prospects of overpopulation were all too real. The solution to overpopulation was population control, an idea the neo-Malthusians began to develop into a widespread movement during the 1930s. Pearl was one of the instrumental figures, both as an ideological and organizational leader, in helping to build this movement. He contributed to it an explicit wedding of eugenical ideology (the question of qualitative control) with the neo-Malthusian doctrine of overpopulation (quantitative control).

In his more strictly scientific studies of population, Pearl investigated growth rates of various socio-economic classes, the relative distribution of age groups in different populations, longevity (duration of life), the vital statistics for various groups in the social hierarchy (e.g., American Blacks, or members of the National Academy of Sciences), the relationship between alcohol and duration of life, the biology of death, and, finally, various methods of contraception. Pearl’s intense interest in birth control and population control is further indicated by the large number of popular articles he wrote and the public lectures he gave during the last 15 or 20 years of his life. He became unquestionably the most vocal exponent of population control ideology within the scientific community. He was the Paul Ehrlich of his day.

Valuable insight into Pearl’s public and popularized views on overpopulation can be found in his scrapbooks, which contain clippings of nearly all of the major newspaper and magazine articles describing Pearl’s work or summarizing his public lectures. That Pearl participated in the somewhat sensationalistic aspect of population control ideology is evidenced by both the titles of his own articles, and the headlines of newspaper accounts of his lectures. For example, the headline for an article in the Baltimore Sun of November 7, 1925 runs: “Population pressure will cause future wars, Dr. Pearl predicts” with the following subtitle: “Hopkins scientist says two hundred million persons is a safe limit for the United States — world saturation in sight, his opinion.” The Cincinnati Post of June 22, 1926 has the following series of headlines for an article on population control:

Fly Universes are Proof

Scientists show earth can hold only five-billion-two-hundred-million

Similar to insects

Maximum population of U.S. is one-hundred-seven-million

The various articles have one theme in common: the world’s population growth rate is such that the maximum carrying capacity of the planet will have been reached in the next 75-100 years; this poses a serious threat not only to the future of the world’s ecosystem, but also to the biological (genetic) quality of the entire species; the question was not should there be birth control, but how much and for whom? To Pearl the answers were straightforward: How much? Considerable! And for whom? The genetically inferior.

Pearl was eager to obtain various kinds of financial support and build organizational and institutional bases for population studies and the propagation of population control ideology. Through his long-standing friendship at John Hopkins Medical School with William H. Welch, who by the 1920s was closely associated with the Rockefeller Foundation, Pearl proposed that the Foundation fund a research center, to be called the Biological Institute, at John Hopkins University. The purpose of the institute would be to study aspects of human biology, particularly those related to reproduction and fertility. After much negotiation the Rockefeller Foundation gave Pearl a sizable grant in 1924 ($175,000 for a five-year period) to organize the institute.

In addition Pearl was instrumental in founding an international group to develop and coordinate population studies in various countries. In this project Pearl was joined enthusiastically by his colleague at Harvard’s Bussey Institution, E.M. East. The organization was to be called the International Union for the Scientific Investigation of Population Problems (IUSIPP).

Pearl and East made the point vigorously that biologists should be represented strongly on the organizing board of the IUSIPP. This was the only way, they argued, that the study of population growth could avoid the kind of errors to which the old eugenics movement had been prone. Despite Pearl’s and East’s personal prestige and intellectual arguments, however, the Rockefeller Foundation was reluctant to become involved in the IUSIPP, largely because the Foundation feared that its name would be associated with an overtly political, rather than a covertly political (i.e., scientific) organization. Ultimately the matter was resolved by the Rockefeller Foundation joining with the Millbank Memorial Fund in a collaborative funding effort, totalling $60,000 over a three-year period.

The involvement of the Rockefeller Foundation in population studies in the 1920s did not represent a wholly new direction in its ideological development. Like Pearl, the Rockefeller Foundation also made a transition (though less dramatic) from interest in and support of eugenical projects, to those related to population control. In the first decade of its existence (roughly 1916-1926), the Foundation funded a variety of projects which were largely eugenical in nature: a long series of investigations on human migration, on organization called the Bureau of Social Hygiene, and its stepchild, the Criminalistic Institute, among others. Although the older, more blatant eugenics movement had been directly funded by the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the Rockefeller Foundation had poured considerable sums into studies of inheritance of social behavior, particularly crime, “degeneracy” and so-called social deviance. Partly under Pearl’s influence, and later guided by more moderate eugenicists such as Frederick Osborn, the Rockefeller Foundation began to assume increasing interest in population questions by the early 1930s. In 1952 John D. Rockefeller III (not the Rockefeller Foundation per se) was instrumental in setting up the Population Council, one of the major private funding organizations in the post-war era for studies of family planning and population control. The director of that organization was Frederick Osborn, who throughout the pre-war period had maintained close ties with staunch eugenicists such as Madison Grant and Harry Laughlin.

What is interesting to note is that the funding for population control was vastly greater in the 1930s and especially after World War II, than was that granted to orthodox eugenics, even in the latter’s hey-day. For example, the Carnegie Institution of Washington allocated an average of about $125,000 a year between 1918 and 1939 for the total budget of the Station for Experimental Evolution and the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor. Of this, only an average of about $21,000, or 16 percent, went for eugenics per se. By contrast, the budget of the Rockefeller-funded Population Council for its first year alone (1952) was $250,000. To this new development Pearl became for the Rockefeller Foundation and the ideology of population control what C.B. Davenport had been for the Carnegie Institution and eugenics: a well-known, respectable biologist who could help to formulate a biological explanation of, and solution for, recurrent social problems.

Conclusion

Throughout his work in both eugenics and population control what remained constant in Pearl’s thinking was: (1) the belief that most human social problems were largely biological in origin and (2) the fear that lack of proper biological knowledge, coupled with an unwillingness to use that knowledge to guide and regulate the human reproductive process, would lead to a serious decline in the quality of the human species. He never abandoned the idea that the socially or economically disadvantaged were also biologically disadvantaged. Where he began to differ with many of his eugenical colleagues was over two issues: (1) the exact genetic mechanisms producing socially defective groups, i.e., the one-gene-one-trait view of the old-line workers such as Davenport and Laughlin and (2) the failure of eugenicists to consider qualitative changes within a population in a quantitative context. From his background in biometrics and animal breeding, Pearl knew that qualitative changes within a population had to be viewed in terms of overall population size and its rate of growth. It was obvious there was no sense in breeding from a few so-called “good” family lines while the rest of the population, of questionable or even neutral hereditary quality, was being allowed to expand at a logarithmic rate. Eugenics made no sense without population control; but at the same time population control made no sense without eugenics. Pearl’s elitism about social groups other than his own may have been less overt than the old-style eugenicists, but he had the same aims at heart.

Conservative to the core, Pearl once said that one of his greatest heroes in the history of American sociololy was social Darwinist William Graham Sumner. As a member of two conservative citizens’ organizations, The Association for the Defense of the Constitution and the Maryland Free State Association, he claimed that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was, at one and the same time, leader of both the American fascist and communist movements! In the mid-1930s, he took a soft, even agnostic position on the dismantling of German universities by the Nazi regime, and tried to discourage at least one member of the Galton Society (a eugenic organization of which Pearl was a charter member) from resigning because the society’s publication, Eugenical News, had carried articles favorable to Nazi race-hygiene. With regard to the situation of German universities, Pearl wrote to his colleague C.F. Close in 1934:

There is a very strong and widespread feeling among university men in this country against the policy of the Hitler Government relative to universities. Personally, I may say that I do not share this feeling quite as completely as do some of my colleagues, because I am disposed to believe that there was at least some measure of justification for the policy upon which the German government embarked. This view means no more than that I am constitutionally predisposed to the view that every question has at least two sides, and I am also predisposed to look at and give consideration to all sides of a question about which I can get information.14

A year later, in attempting to dissuade another colleague, W.K. Gregory, from resigning from the Galton Society, Pearl indicated that he was somewhat less sympathetic with German fascism than he had been in 1934; yet he opposed Gregory’s strong act of protest on the grounds that science and politics should be kept apart:

In considerable part — indeed probably wholly — I share your views about the current political philosophy of Germany, but I must reluctantly confess that I am not clear as to the wisdom of your action in the premises. I have a deep convinction, which I believe you really share yourself, that political considerations should never be allowed to play a part in science, and it does seem to me… that your action in this case is motivated by political rather than scientific considerations.15

What is particularly ironic, in light of the above statement, is that Pearl’s writings show a constant interest in the relationship between biology and socio-political issues. Furthermore, on more than one occasion Pearl wrote openly and disparagingly of racial or ethnic groups different from his own. He once claimed that “The Scotch are a people particularly subject to insanity in all its forms,”16 and felt that the Irish were evolutionarily retarded.17 Particularly strong was his rather generalized anti-Semitism. In a letter to E.M. East in 1927, Pearl spoke out sharply about Gregory Pincus, who was then a colleague of East’s at Harvard (and a rather controversial, but brilliant, developmental biologist):

By the way, who is this Jew of yours named Gregory Pincus who writes me that he wished me to prepare for him “at my earliest convenience” a comprehensive list of references to literature on sterility… just how did he ever get the notion that I have no other amusements in life except making bibliographies for lazy Jews?”18

These quotations suggest just how ingrained was Pearl’s hierarchical and elitist view of human beings. With such deep-seated beliefs, combined with funding from America’s leading ruling-class foundation. Pearl could not have helped but give the ideology of population control a heavily racist and elitist tone.

In the period 1920-1940 Pearl was by no means the only biologist or reformer to transfer his enthusiasm specifically from the eugenics to the population control movement. Among those who made a similar transition were S.J. Holmes, zoologist at the University of California, Berkeley; Edward A. Ross, sociologist and Progressive reformer from the University of Wisconsin; and Frederick Osborn, financier and deputy to the Rockefeller interests. This trend suggests that the ideology of the older eugenics movement did not die out by 1940, as has been claimed, but that a general transformation took place in which the same basic view of human social problems — their origin and their solution — was recast in a different mold. The common assumption of eugenicists and population control advocates was the notion that social problems are caused by innate biological factors — our “human nature.” Whether that “nature” is genes for specific social behaviors, or a more general “reproductive capacity,” the argument is essentially the same. It was the same in Pearl’s view of eugenics, and later in his view of population control. It was, in metaphorical terms, the “old wine in new bottles.”

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 4 <<

REFERENCES

- Haller, Mark, Eugenics: Heriditarian Attitudes in American Thought (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1963); Kenneth Ludmerer, Genetics and American Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972); Provine, William, “‘Geneticists and the biology of race crossing,” Science 182 (Nov. 23, 1973), pp. 788-796.

- Pearl, Raymond, “‘Variation and correlation in brain weight”, Biometrika 4 (1905), pp. 13-104; Pearl, Raymond, “‘Breeding better men,” The World’s Work (Jan. 1908), pp. 9819-9824.

- Pearl, “‘Race Culture,” The Independent (Feb. 24, 1910) pp. 418-419.

- Pearl, Raymond, “‘Variation and correlation in brain weight”, Biometrika 4 (1905), pp. 13-104; Pearl, Raymond, “‘Breeding better men,” The World’s Work (Jan. 1908), pp. 9819-9824.

- Pearl, “‘The First International Eugenics Congress,” Science 36 (1912), pp. 395-396.

- Pearl, Raymond, “‘Variation and correlation in brain weight”, Biometrika 4 (1905), pp. 13-104; Pearl, Raymond, “‘Breeding better men,” The World’s Work (Jan. 1908), pp. 9819-9824.

- Pearl to Bateson, May 27, 1920, from the Pearl Papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

- Pearl, “‘The Biology of Superiority,” American Mercury 2 (1927), pp. 257-266.

- Pearl, “‘Some eugenic aspects of the problem of population,” Eugenics in Race and State: Scientific Papers of the Second International Congress of Eugenics (Baltimore; Williams and Wilkins Co., 1923), Vol. 2, pp. 212-214.

- Pearl and L.J. Reed, “‘On the rate of growth of the population of the United States since 1790 and its mathematical representation,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 6 ( 1920), pp. 275- 288.

- Pearl, “‘Some eugenic aspects of the problem of population,” Eugenics in Race and State: Scientific Papers of the Second International Congress of Eugenics (Baltimore; Williams and Wilkins Co., 1923), Vol. 2, pp. 212-214.

- Chase, Allan, The Legacy of Malthus (New York: Knopf, 1977), p. 134.

- Pearl, “‘The Menace of Population Growth,” Birth Control Review 7 (1923), pp. 65-66.

- Pearl to C.F. Close, December 27. 1934, from the Pearl Papers, APS.

- Pearl to C.F. Close, December 27. 1934, from the Pearl Papers, APS.

- Pearl, “‘The physical characteristics of the insane,” The Independent (July 18, 1907), pp. 157-8

- Pearl, “‘Evolution and the Irish,” The Dial 49 ( 1910), p. 290.

- Pearl to East, May 7, 1927, from the Pearl Papers, APS.