This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Prospects and Problems: The Anti-Nuclear Movement

by Joe Shapiro

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 12, No. 4, July-August 1980, p. 16-21

*Many of the ideas presented here arose out of discussions with friends. l’m particularly indebted to Arnold Cohen, Rod Goldman, Jules, Lobel, Carlin Meyer, Janet Plotkin, Mimi Rosenberg, and Weimin Tchen.

Joe Shapiro teaches physics at Fordham University. He is a member of the North Manhattan local of the SHAD (Sound-Hudson against Atomic Development) Alliance.

This article will attempt an analysis of the anti-nuclear movement, emphasizing how that movement is related to the long-term goal of building a revolutionary movement in the United States.1* Thus a brief statement of the current objective conditions in the U.S. and a discussion of the prospects for success in eliminating dependence on nuclear power as an energy source are needed. It is then argued that the main potential of the anti-nuclear movement is as a mechanism for raising the political consciousness of those actively participating in its struggles. Some historic trends and current problems in the movement are then analyzed. Finally, it is argued that two recent factors — formation of the Citizens Party and increased trade union participation — could change the character of the movement in dramatic ways.

The analysis is highly provisional, and doubtless oversimplified. My main hope is to initiate discussion on the nature, objectives, and potential of the movement. My experience with anti-nuclear organizing is limited, though for many years I have spoken out against nuclear power. Since last fall, I have been involved in New York City, as a member of the North Manhattan local of the SHAD (Sound-Hudson Against Atomic Development) Alliance.

Objective Conditions in the United States

The state of the U.S. economy can be described in a single word — crisis. Interest rates are just starting to go down from record highs. Inflation is near 20 percent. Unemployment is growing, especially in such key areas as automobiles and housing. We are entering a major recession — perhaps the worst since the Depression of the 30s.

The crisis in the economy is matched by a crisis in foreign policy. The Vietnam War left the U.S. military in a position where it could not intervene directly in wars of national liberation, such as that in Angola. A policy developed that had this dirty work done by client states, e.g., using Iranian troops to suppress rebellion in Oman. Through events like the Iranian revolution, this policy has collapsed.

The brunt of the economic crisis is being felt by those groups with the least political power. Thus an assault is being made on the living standards of poor and working class people, through such means as reductions in essential social programs and wage settlements that come nowhere near meeting inflation. In addition, an attempt is being made to reinstitute cold war conditions, so that, for example, armed intervention in Iran can become a possibility. These policies have been singularly successful, partly because of the lack of large-scale, organized opposition. The resurgence of the KKK, the jingoistic support of the Olympic boycott and the “attempt” to rescue the hostages in Iran, and the positions taken by the major presidential candidates all indicate a dramatic swing to the right. The standard of living of poor and working class Americans has declined dramatically.

These factors have all tended to weaken the anti-nuclear movement. Issues of war and peace have become more important. A major anti-draft movement has developed again. People are concerned with economic survival. We are being told that we need nuclear power to stay ahead of the USSR. It is not surprising that the anti-nuclear movement has lost some of its vitality, especially since it is now over a year since Three Mile Island. What is impressive is that the movement has maintained the strength that it has. For example, on April 19, 10,000 people demonstrated against the plutonium plant at Rocky Flats, Colorado.2

Nuclear Power as an Issue

The primary motivation of people involved in the anti-nuclear movement is concern with safety and longterm environmental effects; the main demand, of course, the elimination of commercial nuclear reactors. The movement has had considerable success in satisfying this demand.

Nuclear power costs have soared compared to conventional ways of generating electricity. This is due in part to the installation of safety features, such as Emergency Core Cooling Systems, whose necessity was first pointed out by anti-nuclear activists. This increased cost, plus a slowdown in growth of electricity consumption and the recognition by utility executives that people will resist having unsafe plants built in their communities, has led to a rash of cancellations, postponements, or conversions to coal of nuclear plants. In the U.S., there have been only 13 orders for new plants since the beginning of 1974. In the same period there have been over 60 cancellations. In 1979 there were no new orders and 11 cancellations. 3 The rate of growth of electricity consumption, which historically had been 7-8 percent per annum, is currently only 2-3 percent.4 With the onset of the recession, this rate will drop even more. New fossil fuel plant construction and improvements in existing plants have produced substantial excess generating capacity. Except for a few areas that are especially dependent upon nuclear power, such as Illinois and parts of New England, fossil fuel capacity exists today to replace nuclear power completely. Nuclear’s share of total electricity production reached a peak of 14.1 percent in November, 1978. Due to shutdowns because of questions of safety, both before and after TMI, nuclear’s share had dropped to a low of 8.4 percent by May, 1979, with no major blackouts or reductions in service. Currently, nuclear’s share is about 10 percent.5 This is approximately 3 percent of total energy production in the U.S. With a minimal increase in effort in energy conservation and in developing alternative forms of energy production, commercial nuclear power could rapidly be phased out in the U.S.

It is important to realize that U.S capitalism is split over nuclear power. For utilities owning operating reactors, nuclear plants are the cheapest way of generating base-load power, partly because of government subsidies. Huge investments already made force utilities to get plants under construction operating and into their rate base. In spite of the large number of cancellations, General Electric and Westinghouse, the two major manufacturers, have profitable nuclear divisions because of orders from Third World countries and for existing U.S. reactors, through service contracts and those improvements mandated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) following Three Mile Island. These improvements have been estimated by the NRC to come to over $30 million per reactor, or over $2 billion for the 70 or so reactors in operation in the U.S.6

Other capitalists oppose nuclear power, either because they consider it too risky an investment or they are involved in other forms of energy production. The Bank of America has announced that it will no longer finance new nuclear plant construction. Companies such as Pacific Power and Gas have made major investments in solar technologies. It is worth noting that when interest rates are high (about 17 percent as this is written), investments with low initial capitalization and high operating costs are favored over those for which the reverse is true. Thus, right now, coal is favored over nuclear, which in turn is favored over solar. As the recession deepens and interest rates drop, this order will tend to be reversed.

Nuclear power appears to be neither necessary as an energy source in the U.S. (at least in the short run) nor to be unanimously supported by big business. This implies that the struggle against commercial nuclear power can wholly, or in large part, be won within the structure of U.S. capitalism. It is a reform struggle within which the anti-nuclear movement has had some success, and will doubtless have additional successes in the future.

Political Potential of the Movement

I have just argued that the struggle against nuclear power can be won, at least in part, within the confines of our capitalist system. What then? Will the anti-nuclear activists go back to business as usual, or will they get involved in other issues? After all, the elimination of nuclear power, though a desirable reform, will not eliminate mass unemployment, inflation, racism, sexism, poor housing and health care, or any of the other products of monopoly capitalism.

The key question becomes: How does this particular reform struggle motivate the participants to work for the eventual replacement of capitalism as a social and economic system? I do not pretend to have anything resembling a complete answer, but would like to make two suggestions.

First, people need to believe that the alternative to capitalism is more desirable. Faced with the history of Stalinism in the Soviet Union and recent flip-flops in China, this is a significant stumbling block. Second, one must believe that the overthrow of capitalism is a real possibility: Again, this is not so easy to accept. Socialist revolution has yet to occur in an advanced capitalist country. In addition, there are no strong left organizations in the U.S. at this time. The working class is quiescent. Capitalism is in firm control. Thus one is talking about a long term proposition in a situation where the existing examples of socialist societies are far from ideal. How do people get motivated under such conditions? I believe that people will work to replace capitalism only to the extent that they understand first, how capitalism functions as a system, and second, how their own activities fit into and support that functioning. This understanding is an essential part of believing both that socialism is an improvement over capitalism and that capitalism can be overturned.

This still leaves open the question of how this understanding develops. Here I would argue two points.7 First, it comes out of people’s own experiences. Thus the importance of participating in direct actions. All such actions have limitations, and by confronting these limitations, people may develop a broader political understanding. Second, it is crucial to expose the role of the state. Many people believe the state represents them, through the candidates they elect every few years. In reality, the state represents capitalists as a class, and is an organ for maintaining the privileged position of that class. This fact is hidden in many ways. Particular groups of capitalists frequently are harmed by specific legislation and rulings, e.g., subsidies for airports and the Interstate Highway Act helped destroy passenger rail transportation. In theory, everyone gets equal treatment before the law but in practice only the wealthy do. It is important to get through these democratic forms to expose the underlying exploitative essence. From a tactical point of view, actions directed toward the state are of the utmost importance, as opposed to actions against small groups of capitalists.

Within this framework, the anti-nuclear movement has much to be said in its favor. The state has played a major role in the development of nuclear power, because of the close relationship between reactors and nuclear weapons. Though originally the movement relied exclusively on lobbying, education, and intervention in hearings and court cases, its tactics have expanded to include direct actions with large scale civil disobedience (CD), i.e., from complete legality to a willingness to undergo arrest. Participation in these activities has, in many cases, increased the level of political consciousness of the participants. In addition, the movement has gradually become more directed toward class issues. For example, consider the actions of last October 29. After years of protests against individual reactors or plants (against small groups of capitalists), there was a major demonstration at Wall Street (certainly a center for capitalist class interests) and a smaller demonstration in Washington at the Department of Energy (against the State). Finally, there has been a broadening of the issues involved. Originally, the anti-nuclear movement concerned itself solely with the safety of nuclear power and the threat of nuclear war. Today, a host of additional issues have been introduced, including the oppression of Native Americans (who get lung cancer from mining uranium in mines owned by large corporations but situated on Native American lands), the role of the government in subsidizing and promoting nuclear development, nationalization of the oil companies (which have large holdings in the uranium industry), high utility rates, and opposition to synfuel development. Support has been given to the struggle against reactor development in the Philippines pines.

Problems within the Movement

I have tried to argue that there is nothing revolutionary, per se, about nuclear power as an issue, and that its main potential is long-range: helping the development of political consciousness among its participants. I have further argued that this has started to occur. This has not been due to the conscious activities of “leftists” within the movement: rather it reflects the special nature of the particular issue (major involvement of the government, beginning with the Manhattan Project) and the growth of a substantial anti-monopoly movement in the U.S.

Unfortunately, the position presented so far is much too optimistic. The overall level of political development of the movement is low: there is strong opposition to broadening the issues. For example, the last of the five demands for the April 26 rally 8, to “honor Native American treaties,” was added quite late and, apparently, after considerable debate.9 The movement is almost exclusively white and petty-bourgeois. It is worthwhile examining some of these questions.

Practically everyone in the movement is in favor of nonpolluting, safe, renewable alternatives such as solar, wind and biomass. Great. But another prevalent view is that these technologies can be developed in small, decentralized ways, and that through this development new social relations will arise that will serve as a model for “restructuring society.” Though this position has many positive aspects, such as fostering self-reliance, it must be rejected as utopian. It is an example of technological determinism, i.e., it assumes that new technological developments determine how society evolves, rather than technology and social forces mutually influencing each other. More explicitly, the development of decentralized renewable alternatives will not change the nature of monopoly capitalism — the banks will control loans, corporations will control patents, and the small-scale equipment will be mass-produced by large companies more cheaply than it can be made by the small entrepreneurs. A good example is solar collectors for home and hot-water heating. Several companies, including G.E. and Westinghouse, the two major manufacturers of nuclear reactors, are working on solar collectors made of evacuated tubes with selective coatings; G.E. is already marketing theirs, the Solartron.10 Though more expensive than the “home-made” flat plate collectors, they are much more efficient. Further, both manufacturers have substantial experience in producing fluorescent light bulbs; this will enable them to introduce mass production techniques and cut costs. If G.E. and Westinghouse both fail in this venture, some other corporation will eventually mass produce collectors cheaply and put the small flat plate manufacturers out of business.

The emphasis on alternative technology partially reflects anarchist tendencies within the movement. These tendencies also show up in the emphasis on consensus decision making. There has been interminable debate about the pros and cons of this technique, which is admittedly slow and unwieldy in some circumstances. It might be worthwhile noting that our SHAD local decided against using consensus when it formed last fall. To date all decisions have been reached unanimously, i.e., by consensus! The main problems within the antinuclear movement are political, not organizational. Blaming a particular form of decision-making is often a way of not discussing political issues. An attempt by a few individuals within SHAD to organize discussions on the political goals of the organization was a dismal failure; it collapsed after one poorly attended meeting.

Historically there has been, and still is, a large pacifist tendency within the movement, as exemplified in the New York City area by the War Resisters League. This history accounts, to a large extent, for the continued emphasis on nuclear weapons as well as reactors. It also accounts for the emphasis on civil disobedience as a tactic and on nonviolence as a principle. I would certainly agree that the antinuclear movement should be non-violent, as a tactic. This is not based upon moral principles, however; nuclear power is a non-revolutionary issue in a non-revolutionary period in U.S. history. Under these conditions, violence would be counter-productive.

This emphasis on CD, though important in building the movement, has recently had some negative effects. People participating in CD operate in affinity groups, and under conditions where people get arrested, strong personal ties grow. Affinity groups can thereby develop a permanent existence. SHAD is an alliance of both affinity groups and geographically-based neighborhood locals. Within SHAD people have moved more and more out of the locals and into affinity groups; most locals have collapsed (ours is one of the few exceptions), and with them much of the organizing and outreach. Many of those involved in the movement seem to believe that organizing can be done by example, rather than by getting out and doing grass roots work.

Attempts to draw Blacks or Hispanics into the movement have been singularly unsuccessful. One difficulty is with the tactics employed. Undocumented workers, people on parole, and anyone who cannot risk being fired from their job by being arrested are excluded from participating in CD. Actions frequently are held outside the cities where most minorities live, and are expensive to get to. But this is not the whole story. Insufficient effort has been expended on combatting racism within the movement or on trying to understand the concerns and problems of minorities.

Where does all this leave us? The anti-nuclear movement has lost considerable momentum. On the other hand, nuclear power, and energy in general, will not disappear as issues. The movement will survive. But nuclear power is merely one issue out of many facing the Left. For the movement to remain dynamic and to increase the political consciousness of its membership, this issue must be tied to others. As pointed out above, this is beginning to happen. There are two recent developments, both in their infancy, that could accelerate this trend. Both also will cause internal problems.

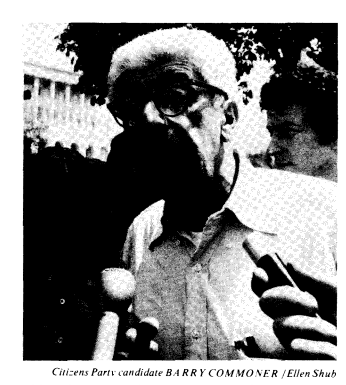

One split that has existed within the movement is between those, e.g., Ralph Nader, Barry Commoner and Tom Hayden, favoring electoral activities and large legal rallies versus those favoring direct action with civil disobedience. Though there have been attacks back and forth, an uneasy truce has prevailed. However, the formation of the environmentally-minded, anti-nuclear Citizens Party has brought the question of electoral activity to the fore. Anti-nuclear groups and individuals will be forced to decide to what extent they are going to get involved. Because of the strong anti-electoral bias within the movement. and the emphasis on consensus. it is unlikely that many of the grass roots anti-nuclear groups will actually endorse the Citizens Party, but many anti-nuclear activists may support it.

Although for many it simply expresses rejection of the political process, the anti-electoral attitude has a perfectly valid basis; namely, that reforms are won through militant mass actions, not by appeals to politicians. However, this ignores electoral work as a means of education, or possibly as a way of getting people involved in mass struggles. Certainly the Citizens Party has limitations. It will not develop into a revolutionary organization. But it is a progressive party that has taken an antinuclear position. It has some potential for becoming a political force during a period when the country is rapidly becoming reactionary and when nothing else exists. Success of the Citizens Party will strengthen the movement. It’s hard to see any rationale for members of the anti-nuclear movement not supporting it. But many won’t.

The second and potentially more important development (because it involves a change in class composition) is the growing participation of trade union groups. Although many workers have supported nuclear power through counter-demonstrations at construction sites, there has also been a long history of union opposition. William Wimpinsinger, president of the Machinists Union, and Anthony Mazzochi of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, have consistently been anti-nuclear. District 31 of the Steelworkers, representing 130,000 members, took a position against nuclear power in 1978.11 Miners for Safe Energy, a rank and file group from Steelworkers Local 7044, which represents gold miners in Lead, SD. has been active in opposing uranium mining in the Black Hills (see Newsnotes, this issue).

Labor union support took a qualitative leap forward with the April 26 demonstration. Several union bodies endorsed a statement of support: these included the Machinists Union, the International Woodworkers Association. the American Federation of State. County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the International Chemical Workers Union, District 1199 Hospital Workers, Local 170 of the American Postal Workers Union, District 6 of the United Mine Workers and Local 65 of the Steelworkers. In part the statement said

We know that a cheap and alternate source of energy exists in immediate and almost inexhaustible supply – coal. Technology is presently available to mine and burn coal safely. A longer term goal is the development of other safe energy sources such as solar, water, wind. which would provide more jobs than producing nuclear energy.

Trade unionists should take the lead in this struggle for we truly have no alternative. Our lives and the lives of our children are at stake. Every minute brings closer the danger of another Three Mile Island in the nuclear processing and nuclear power plants that continue to operate.

We have the power to shut these plants down and it is in our interests to do so. Many of these plants also produce the materials used in atomic weapons, weapons that, if used, would destroy the entire world. This madness must end. Working people have no interest in a world armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons.12

A well-organized and vocal group of coal miners and steel workers participated in the march and rally. However, their chant, “No Nukes, Use Coal”, does not sit well with supporters of alternative technologies. This points out one of the dilemmas the movement faces. For years, it has been looking for worker and minority support. Now it may get both, since many of the unions mentioned above have large Black and Hispanic memberships. But the unions will also bring with them different positions, different tactics, different leadership, and a different political outlook. These will not be popular with large segments of the movement.

It is too early to say whether these developments will become important. The Citizens Party may flop. The majority of workers still support nuclear power. Trade union support may not continue to grow. However, either development would force a further broadening of the issues involved, and cause dramatic changes in the character of the movement. The anti-nuclear movement may never be the same again.

>> Back to Vol. 12, No. 4 <<

REFERENCES

- See also an article in Point Magazine. Nov. 1979, reprinted with minor deletions in The Guardian, Feb. 13, 1980. Point is published by students at Fordham University.

- The New York Times. April 21. 1980.

- The New York Times. March 16, 1980.

- U.S. Department of Energy. Monthly Energy Review. March 1980.

- Ibid.

- The New York Times. April 30,1980

- These points have been emphasized by Lenin. See, for example. What is to be Done?

- A major anti-nuclear rally occurred in Washington. D.C. on April 26. The rally received very little media coverage, in contrast to the hostage rescue “attempt” which occurred the same weekend.

- Josh Nessen, “Link Antinukes. Racism.” The Guardian. April 9, 1980.

- B.J. Graham, “Evacuated Tube Collectors.” Solar Age. Nov, 1979. p. 12.

- Rebecca Logan and Dorothy Nelkin. “Labor and Nuclear Power.” Environment. March, 1980. p.6. This article gives a good historical survey of trade union involvement in opposing nuclear power.

- Quoted in Labor Notes. April 24, 1980. p. 13. Published by the Labor Education & Research Project. P.O. Box 20001, Detroit, MI 48220.