This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

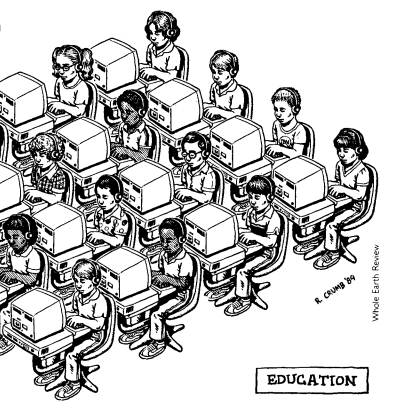

Computers in the Classroom: Social Stratifiers or Liberating Equalizers?

by Marcia Boruta and Hugh Mehan

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 17, Nos. 1 & 2, March/April 1985, p. 41 — 44

Marcia Boruta and Hugh Mehan are members of the Computer Use Study Group of the University of California, San Diego, which undertook the study they describe.

Computers are being promoted as the educational tool of the 1980s. Almost daily, we are being informed of the dangers of a computer illiterate society, and with almost blind faith, schools are taking on the responsibility of supplying computer education. As history has shown us, however, innovations in social systems often have unforeseen consequences for those systems. 1 As schools acquire and use computers for educational purposes several major questions arise:

- Will students from different strata of society obtain equal access to computers?

- Will students from different strata of society be taught similar or different uses of computers?

In order to get some sense of the relationship between the numbers of computers in schools and students’ access to computers, we observed computers being used in 21 classrooms in five Southern California school districts.

We did not select these schools according to a formal sampling procedure; we capitialized on personal contacts to facilitate access. Since our schools were not sampled randomly, care must be taken when generalizing from the information that we obtained. Likewise, we did not randomly sample the people to be interviewed. If there is a formal term to characterize our approach to interviewing, it would be called the “snowball technique.” We started with the teacher, resource person, or whomever we could find who knew about computers in the school. When an interview was completed, we asked that person for the name of others involved in computer use, and interviewed them. We continued this procedure until there was no one left to interview.

Our observations and interviews were guided by a common set of orienting questions regarding the relationship between the characteristics of schools, the students they educate and the policies and practices of computer use in the five districts we studied. We found a very strong relationship between (1) the rationale for computer use, (2) the source of funding for computer acquisition, (3) the type of students who are educated using computers, and (4) the type of instruction presented to students.

The Rationale for Computer Use

We asked school officials why they were introducing computers into the school curriculum. Educators’ answers included: “we want kids to feel comfortable with computers;” “we want students to learn programming … it is an important skill;” “students can gain control of the medium by learning to program it;” “computers can help teach academic subjects;” “computer awareness; “we need to raise test scores . . . we think computers can help us do that.”

We often found that different educators in the same district had inconsistent answers to our questions. Initially, we treated these responses as indicating the novelty of computers in education which creates discrepancies in the reasons cited for their use. Subsequently, we found that educators’ reasons for acquiring and using computers were not randomly distributed. They lined up with the sponsorship of computers and the students who used them.

Funding for Computer Acquisition

The school districts we observed spent very little of their own money to acquire computers, which is not the prevailing national norm. (This finding may be unique to the districts we studied, or it may be a function of Proposition 13, the tax initiative which reduced the money available to school districts in California.) Funds from the state of California and the Federal government purchased 93% of the computers in these districts, by the way of moneys available for education of “gifted and talented” youngsters (GATE), “economically and culturally disadvantaged” students (Chapter 1 of the Educational Consolidation Act of 1981), School Improvement Programs (SIP), and the desegregation effort. Private funding, most notably donations from PTA groups, accounted for 5% of the computers acquired. PTA groups sold land, sponsored “jogathons,” collected aluminum cans in order to acquire computers. One enterprising teacher had a local computer store “sponsor” her classroom in exchange for the loan of microcomputers.

Student Access to Computers

The stated policy of many schools that have computers is to give all students equal access to computers for instructional purposes. However, the disparities between stated policy and observed practice point to the potentially statifying effects of computer use.

We also found that boys and girls had differential access to computers, especially in secondary schools. In elementary schools with central lab facilities, boys and girls had equal access. However, observation of voluntary time on computers (for example, at lunch and recess) revealed more boys than girls using computers in their spare time. The statification of boys and girls on computers coincides with the curricular divisions of boys and girls in math and science subjects.

We also found that there is a relationship between the source of funds used for computer acquisition and the students who had access to these computers that has a stratifying effect. Chapter I and SIP funds were used primarily to educate ethnic minority and lower class students on computers, while GATE and private funds were used primarily to educate middle and upper middle class students.

For example, Chipotle School, established as a computer “magnet” school to attract white families to an inner city ethnic neighborhood, functioned almost as two separate schools. It provided self-paced computer classes for each of its six grade levels and supporting activities in math and science. Ethnic minority students from the local neighborhood (who were not part of the magnet program) only had contact with computers in Math and English Skills Labs. The Skills Labs stress basic skills using the computer for drill and practice and a specialist for tutoring. Most of the white students in the magnet had access to the computers for programming and problem solving activities. Likewise in the Piquin School District, which has a “multiple use” policy, there are differences in student access to the computers. In the schools where computers are assigned exclusively to GATE (Gifted and Talented Education) classrooms, each GATE student averages 60-80 minutes per week on the computer, and other students have no access to the computers at all.

Computers fortunately were not limited to the groups for which they were acquired originally. After a year or two, computers acquired for GATE students began appearing in regular classrooms. In the schools that rotate computers between GATE classrooms and other classrooms, each GATE student has 40 minutes per week on the computer, and other students have 20 minutes per week on the computer. Clearly not all students in regular education gain access to the computer under this arrangement. Even in the schools where teachers who ask for computers can get them, not all teachers do ask. Thus, where computers are being used in regular (that is, not GATE, Special Education, or Chapter I) classrooms, it is because teachers are highly motivated or highly knowledgeable.

Instructional Applications of Computers

We found that the instructional applications of computer use were differentially distributed. Ethnic minority and lower class students received a different kind of instruction on computers than their white middle class and ethnic majority contemporaries. While white middle class students, especially those who were in GATE programs, received instruction which encouraged learner initiation (programming and problem solving), lower class and ethnic minority students, especially those in Chapter I programs, received instruction which maintained control of learning in the machine (computer-aided drill and practice.)

Computers were primarily used for basic skills instruction and computer literacy. When computers were used for basic skills instruction, students were given computer-aided drill and practice on material which supported instruction they received in their classrooms. When students were exposed to computer literacy, they were taught how to program computers, mostly in BASIC. Computers were used for writing, music, and art far less often than they were used for CAI (Computer Aided Instruction) and programming.

Using computers for drill and practice or computer literacy represents educational policy that should be examined for several reasons. The full power and range of computers is not being exploited when they are used for drill and practice in basic skills. There is little evidence to suggest that computers can deliver basic skills better than conventional techniques such as workbooks or flashcards, and their utility diminishes when their high cost is taken into consideration. 2

The use of computers for computer literacy emphasizing programming does not match the needs of the world of work. While it is true that computers are being introduced into a vast number of jobs, the largest number of jobs will continue to be in the service sector.3 Few of the computer jobs will require high levels of programming skill and computer knowledge. In fact, many jobs are simply being eliminated by computers, while others become less creative. The jobs that are being transformed by computers include (1) those which involve computers but require no knowledge of computer programming by the worker (e.g. supermarket checkers), (2) jobs that require minimal knowledge of computer programming (e.g. text editing, spread sheet analysis and data retrieval), and (3) jobs that require both knowledge and computer use and programming (e.g. systems analysis). This third category is the smallest in scale and hardly justifies organizing entire educational curricula with computer programming at the pinnacle.

Thus the use of computers makes a difference in a way that well-intentioned educators have not considered. By even tracking students from different socioeconomic backgrounds through different computer-based curricula, and by encouraging curricular division between boys and girls, the computer can be used as a tool to contribute further to the stratification of our society. Unless educators become more familiar with the strengths and limitations of computers and establish the uses of computers based on sound educational objectives, then we will be faced with a system of stratification based on technological capital that will make the one based on economic and cultural capital look pale by comparison.

>> Back to Vol. 17, Nos. 1-2 <<

REFERENCES

- S. Sarason, The Culture and the School and the Problem of Change. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1982.

- Mark Tucker, “Computers in Schools: A Plan in Time Saves Nine.” Theory into Practice, vol. 22 no. 4 1983, p. 313-320.

- Russell W. Rumberger and Henry M. Levin, “Forecasting the Impact of New Technologies on the Future Job Market.” National Institute of Education, Project Report No. 84-A4, February, 1984.