This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Supporting Repression: U.S. Military Supplies Salvadorean Regime

by Arnon Hadar

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 2, March/April 1981, p. 34–38

Arnon Hadar is a member of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) in San Francisco, CA.

Introduction

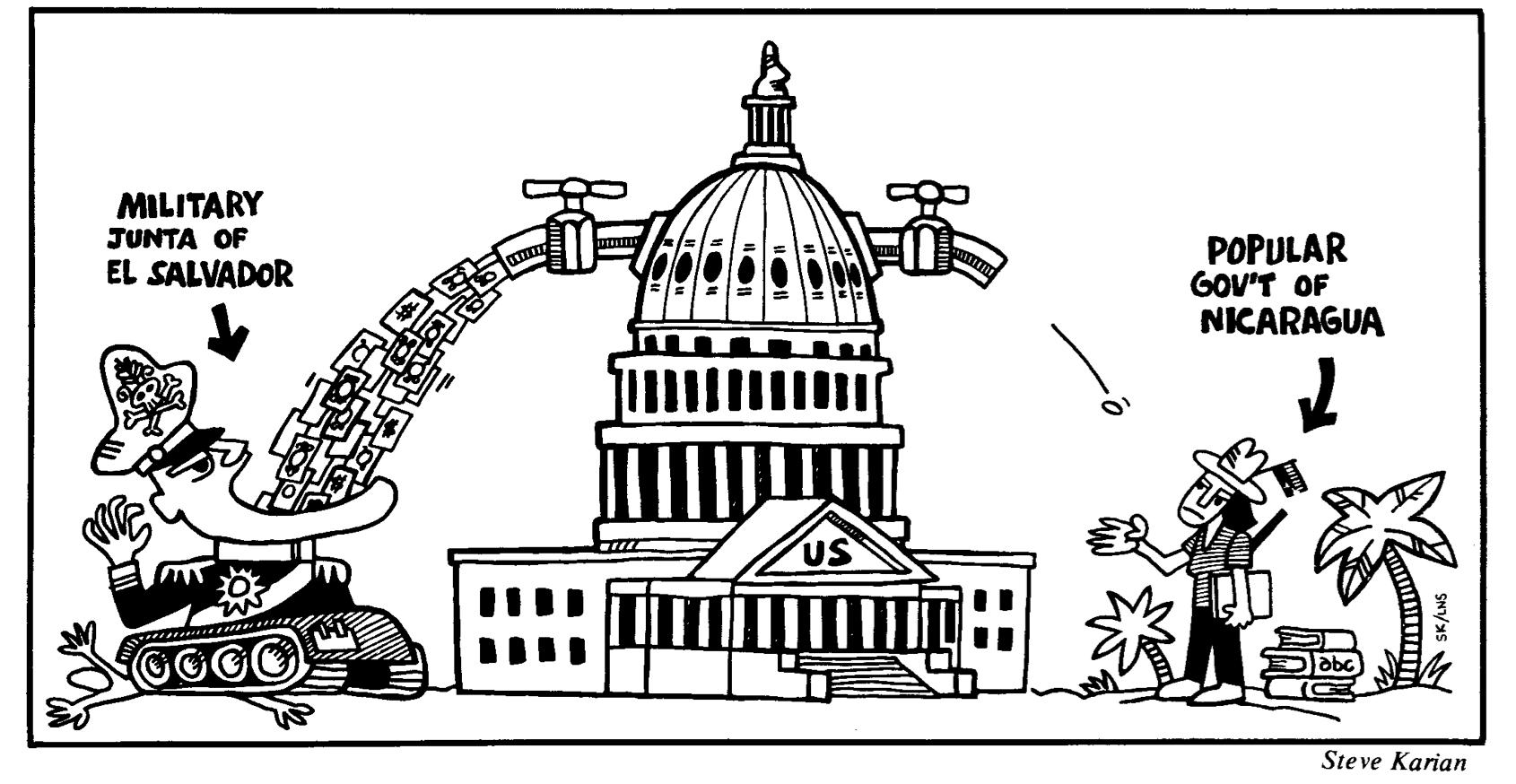

U.S. military involvement in El Salvador — as in all of Central America, the Caribbean and South America — promotes, and actually implies, repression. It consists of arming, coordinating, and training undemocratic regimes so that U.S. interests can be maintained. As the Salvadorean revolution progresses, inspiring popular liberation movements and weakening existing dictatorships, U.S. economic interests throughout the region become more precarious and the U.S. military presence increases. The threat of a direct military intervention in El Salvador is very real.

It should be noted at the outset that the U.S. military role in El Salvador has nothing to do with U.S. national sovereignty or security, nor with “preserving democracy.” Rather, it has to do with maintaining, defending and encouraging the economic interests of U.S. multinationals. Hence, the terms “U.S. role” and “U.S. interests” are synonymous with the interests of the U.S. multinationals and U.S. regional strategy, not those of the people of the United States.

The full significance and extent of U.S. military involvement in El Salvador is hard to measure, for much of it is clandestine and surfaces only by accident. For example, the U.S. Customs Service announced on March 18, 1974, that its agents had seized an illegal shipment of $22.5 million in military helicopter parts en route to El Salvador from Long Beach, California.1The value of this single shipment was greater than the combined value of all official U.S. military aid to El Salvador for the 33 year period 1946-1979. On April 9, the Miami-based Consul General for El Salvador, a Salvadorean Army major and the director of El Salvador’s telephone system were arrested after they were caught trying to smuggle riot shotguns, rifles, rounds of ammunition, and other military items. Thus, to calculate the real amount of aid one would need access to the books of the CIA and the multinational corporations. As we know from ITT’s role in the overthrow of Allende in Chile, Litton Industries’ critical role in the 1967 coup in Greece, and Firestone’s influence in Liberia, illegal military aid from the multinationals can be formidable; United Fruit (United Brands) actually had its own armed bands and airplanes in Honduras.2

A further difficulty in assessing the extent of U.S. involvement comes from the use of second parties as weapons conduits. Israel, France, Venezuela and Brazil are El Salvador’s major suppliers of arms, and while these arms are often manufactured in the U.S., the United States does not officially supply them. Rather, the U.S. sets up a “multilateral assistance effort” whereby second parties deliver the goods. With the power to force Western countries to curtail, or even cut, economic relations (consider Iran, 1980), the U.S. also can promote such relations: an announcement of $5 million in aid to El Salvador from West Germany came in February, 1980, on the heels of a visit to West Germany by William Bowdler, Carter’s Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America.

In military training and coordination, the scope and character of U.S. involvement is more visible. In 1964, the ministers of defense of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua, all of which were under military regimes, established CONDECA (Central American Defense Council), whose purpose was to coordinate and centralize military command of the region through the U.S. Southern Command in Panama. Closely supervised by the CIA, CONDECA’s international staff of high level army and security officers claim credit for a great many counterinsurgency efforts, including the defeat of a Christain Democratic coup in El Salvador in 1972, interventions in Nicaragua and Guatemala during 1976 and 1977, and attacks on the FSLN (led by General Dennis McAuliffe, head of the U.S. Southern Command).

One of CONDECA’s major functions is to protect U.S. (multinational) interests by maintaining “stability” in the region. But it must be understood that this “stability” does not exclude violence. Violence which promotes “stability” is supported by the United States in El Salvador as in other parts of CONDECA’s domain.

Under such conditions, the distinction between military and economic aid blurs. Computers, for example, are a form of economic aid, but are used in some Latin America countries to keep track of dissidents and to pinpoint individuals for arrest, interrogation and assassination.3 Plainly, U.S. military and economic aid not only strengthens the military in El Salvador and elsewhere in Central America, but actively promotes repression — all in the name of “stability”, and in spite of offical advocacy of human rights.

U.S. Direct Military Involvement in El Salvador

U.S. direct military involvement in El Salvador has at least four major elements:

1) Supply of arms to the ruling junta;

2) Training of Salvadorean armed forces;

3) Stationing of U.S. military personnel in El Salvador;

4) Training and supplying other regimes in the region, to enable them better to support the junta in its efforts to crush the mounting popular resistance to its atrocities.

Supply of Arms

U.S. military involvement became increasingly important following World War II, when El Salvador received its first U.S. grants under the Military Assistance Program (MAP), as well as its first military mission. Between the years 1950 and 1969, officially sponsored security assistance from the U.S. to El Salvador averaged about $400,000 annually. In the period 1970-75 it was approximately $1,400,000, an increase of 250%. In 1976 U.S. military aid increased again by 57%.

With this background one can better understand the $5.7 million security assistance appropriation by the U.S. for El Salvador in 1980, the $92 million in “economic” aid, and the $5.5 million in military aid for sales and training credits for fiscal year 1981. This aid is complemented by substantial (over $100 million) loans by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In the next two years, expected U.S. military aid to El Salvador will increase annually by another 150%. To all this must be added the indirect aid which the U.S. provides through its allies. Since 1974, Israel, France, and later, Brazil have played important roles in supplying arms.

Clearly, the 1970’s brought a rapid escalation of U.S. direct and indirect military aid to El Salvador. This aid became a major factor in the regime’s ability to maintain control, and has contributed to its increasing brutality.

U.S. Military Training

The U.S. trained 1,925 Salvadorean officers during the period 1950-76.4 In the period 1970-75, training of foreign military personnel at the U.S. Army School of the Americas, Panama Canal Zone, included 298 Salvadoreans, 108 of whom were trained for basic combat and counterinsurgency. The result was that “… our security assistance program facilitates our overall relations with the government of El Salvador and fosters useful professional contacts with key members of the Salvadorean armed forces.”5 This statement is a good example of the intentions and implications of U.S. assistance. The U.S. consciously tries to strengthen its relations with the higher echelons of the army — to the extent that these contacts are “useful” in practice (i.e., they promote U.S. interests in the region).

In 1957, the U.S. instituted a Public Safety Program under the auspices of the Agency for International Development (AID), which undertook “… to develop the managerial and operational skills and effectiveness of Salvadorean civil police forces.”6 These “effective” police have been responsible for the murder and disappearance of thousands of Salvadoreans since the early 70’s. Between 1957 and 1974, when the program terminated, the Office of Public Safety spent $2.1 million to train 448 Salvadorean police and provide arms, communications equipment, transport vehicles, and riot control gear. Thus, a closer relationship has developed between the U.S. defense and political authorities and the Salvadorean police.

It must be emphasized that the U.S. role in training the police was the major factor in making the police an effective and “efficient” instrument of the oligarchy and a guardian of U.S. interests. We see this in the AID analysis which says “… the National Police … has advanced from a non-descript, cuartel-bound group of poorly trained men to a well-disciplined, well-trained, and respected uniformed corps. It has good riot control capability, good investigative capability, good records, and fair communications and mobility.”7 Many of those trained in the program occupied “key” positions in the Salvadorean security establishment.8

An additional revealing aspect of this program is that while it was initially concerned with training the National Police, from 1963 to 1974 the program’s emphasis shifted to the National Guard. The National Guard became much more directly involved in the repression of working people, especially the peasants.

U.S. Military Personnel In El Salvador

In 1948, we sent our first military mission to El Salvador, a group from the United States Air Force. (We already had an Army officer in charge of training at the Salvadorean military academy.) By l96l…we had both a large Army mission and Air Force mission. In fact, there were more men in the Air Force mission than El Salvador had either pilots or planes.

Murat W. Williams, U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador 1961-64

Available information is too scanty to allow for an exhaustive account of U.S. personnel in El Salvador. With the increasing arms sales in the 1970’s, it can be assumed that the number of U.S. advisers of all sorts also increased. Even during 1977-78, when U.S. military aid was suspended, the U.S. maintained a military assistance group in El Salvador.9 Until recently, military personnel played a minor role in achieving U.S. objectives, but as we will see, this role has become more and more important since General Carlos Romero was ousted in October, 1979.

In February, 1977, when General Carlos Romero took power after an election that was internationally recognized as fraudulent, protests and demonstrations escalated, culminating on February 28 when police and the National Guard began firing on demonstrators. During the following days, hundreds of people were killed. These events brought U.S. human rights policy into conflict with the Salvadorean regime and led to a temporary halt in U.S. aid to El Salvador. What was not officially reported, but claimed by eye witnesses, was the involvement of U.S. personnel in directing the Salvadorean police and soldiers in their armed confrontations with the people. This is another instance of a contradiction between U.S. official policy and U.S. deeds.

The Recent Situation

The most important aspects of the U.S. military role in (and effects on) the present situation are:

– the Salvadorean regimes’ increasing violence and brutality;

– increased U.S. military support to sustain the present regime and state apparatus;

– increased U.S. organization and coordination of other regimes in the region, in preparation for their direct support of the shaky Salvadorean regime, including the possibility of military intervention.

All these measures are necessary to prevent the overthrow of the present regime and the economic, military and legal system on which it is based. A victory by the popular-democratic forces means not only that the oligarchy, the army and the police lose privileges, but that U.S. multinationals lose those extremely favorable conditions for extracting wealth from El Salvador, and controlling this strategic region. In this context, no other option is left to the U.S. and the ruling oligarchy, but to take the measures outlined above.

Violence by the Junta Against the People

The increasing number of murders by the police, army, and paramilitary forces are so well known that we shall dwell only briefly on this escalation of repression. Of the more than 9,000 persons who have been killed in the first eleven months of 1980, the majority were murdered by the various security forces, despite U.S. State Department and press claims that only “right-wing terrorists” have been involved.10 The assassination of Archbishop Romero in March, 1980, highlights the regime’s brutality. The state of siege imposed on March 6, 1980, for 30 days has been extended indefinitely. These facts alone are sufficient proof of state violence.

Direct U.S. Military Participation

In November 1979, the U.S. government authorized the sale of $206,000 worth of tear gas, gas masks, and protective vests to El Salvador’s security forces. A six-man U.S. military team arrived in El Salvador on November 12, to train security forces in riot control. On December 15, 1979, a military operation was carried out against LP-28 (a popular organization) members who occupied the hacienda El Porvenir in El Congo. Nearly 100 people were killed. U.S. soldiers participated, according to eye witnesses.11

In March 1980, U.S. mobile military training teams composed of 36 advisers arrived in El Salvador to train Salvadorean soldiers in counterinsurgency in three centers which also serve as helicopter bases. Since August, eight Navy ships (including an aircraft carrier) with over 2,000 marines have been patrolling the Pacific Coast of El Salvador. During that month, five North Americans were reportedly killed in combat in El Salvador. Since then, North Americans have increasingly participated in military actions. For example, on November 19, Security Forces attacked the office of the Archdiocese in San Salvador, reportedly with the participation of U.S. military advisers.12

The Regional Framework

The geographical framework of U.S. military involvement in El Salvador must encompass at least Central America and the Caribbean. This is the context within which U.S. military involvement has actually been taking place; and only within this context is it possible to appreciate and understand the dimension, the seriousness, and the danger of U.S. military involvement in El Salvador.

U.S. policy has always explicitly taken into account the interdependence of the whole Central American region. A State Department policy maker said, “We are prepared to swing with change and ready to get in there and fight it out. We are not going to be left behind and out of it. Our national interest is involved and we owe it to Central America.”13 On October I, 1979, President Carter vowed to expand U.S. military maneuvers in the region; by the following March the U.S.S. Manley and the Nassau, an 800-foot amphibious assault ship, with combat helicopters aboard, were in the waters of Central America.14 It has been widely reported in Latin America that U.S. military advisers are training a right-wing army numbering about 3,000 in Guatemala and about 4,000 in Honduras (composed of Somoza’s ex-National Guards and other right-wing patriots) for an invasion of El Salvador.15

Through its military aid and guidance, the U.S. has actively sought to amplify national conflicts into regional ones. This internationalization has been carried out on three levels:

—First, through coordination of the military forces in the region, especially among the key members of these forces. Since the beginning of the 1960’s, joint forces, e.g., CONDECA, have continuously intervened in various countries in support of the oligarchical-military regimes and against the popular-democratic movements.

—Second, the U.S. has actively encouraged western countries (e.g., West Germany, Israel, Spain) to supply arms to El Salvador and to countries throughout the region.

—On the third level, the U.S. has consistently and vocally raised the false Cuban “threat” to its security and the stability of the region. U.S. economic and strategic interests in Latin America required an increasing cooperation among the antidemocratic and repressive regimes in this region. The “Cuban threat” was, in part, raised in order to facilitate this cooperation, especially military cooperation.

After the success of the popular-democratic revolutions in Grenada and Nicaragua, the U.S. has been taking even more extreme measures than it did in these countries in order to prevent a popular-democratic revolution in El Salvador. These measures have made it increasingly clear to the poor, churches, and the middle classes in these countries that their socio-economic liberation is directly and visibly standing in contradiction to U.S. imperialist interests, and the mutually dependent oligarchical-military interests.16 It must be stressed that this understanding is emerging in the exploited sectors of all countries in this region.

During the past year, the involvement of the armies of Venezuela and Columbia in preparation for invasion into El Salvador, and the military training of Salvadorean officers by Argentina, and the U.S. Army School of the Americas in Panama have increased tremendously.17 These activities plus the frequent help provided by the armies of Guatamala and Honduras to the regime in El Salvador, are all part of a coordinated plan, under the military guidance of the U.S., to intervene in El Salvador in order to try to stop the liberation struggle in its last stage.18

Conclusion

As we have seen, the U.S. role in El Salvador and the Central American region has several dimensions. In addition to training military and police forces, the U.S. has been the main arms supplier to the region, with a regional policy aimed at unifying the forces of repression and defending multinationals against popular liberation movements. Arms sales, military exercises, and the number of U.S. military personnel in El Salvador and the region have escalated tremendously in recent years, especially since 1979.

Confrontations between the popular liberation forces and the oligarchical-military forces broaden and deepen, largely as a result of U.S. policies in El Salvador and the region. The extreme repression of the people and of the church, and the inability of the people to effect change through years of peaceful attempts, is a byproduct of the U.S. role in El Salvador, and this fact is recognized by the Salvadorean people.

The success of the Salvadorean revolution — the overthrow of the present regime, the abolition and replacement of the existing state apparatus by a popular-democratic one, the elimination of repression and the end of U.S. domination over the lives of the people of El Salvador — will show the popular liberation movements in the other countries that such transformations are possible. It is precisely this situation, and its dynamics, which make the unfolding revolution in El Salvador of special importance.

The U.S. has already intervened in El Salvador, in an effort to halt the transformation of economic and social relations. U.S. military personnel are already present; U.S.-made tanks, helicopters, arms, and bombs are killing Salvadoreans daily. This intervention must be stopped, and the complete withdrawal of U.S. economic and military aid and of the U.S. military presence must be demanded. It is the responsibility of all freedom-loving people in the United States to oppose U.S. backing of the repressive oligarchical-military regime in El Salvador, and to support the popular liberation forces of that country in their just struggle for freedom.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 2 <<

References

- New York Times, March 19, 1974.

- For more examples, see Richard Barnet and Ronald Muller, Global Reach, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1974.

- Computer Decisions, February 1977.

- See “Supplying Repression,” by Michael Klare, The Field Foundation, 1977, p. 20.

- U.S. Department of Defense, Congressional Presentation Document: Security Assistance Fiscal Year 1978, Washington, D.C., 1977, p. 323.

- U.S. Agency for International Development, Phaseout Study of the Public Safety Program in El Salvador, Washington, D.C., 1974.

- Ibid., p.3

- “Background Information on Security Forces in El Salvador and U.S. Military Assistance”, Institute for Policy Studies, 1980, p. 7.

- New York Times, March 8, 1978.

- Boston Globe, January 19, 1981, UPI report.

- New York Times, March 12, 1980.

- Report on El Salvador. Newsletter of the Religious Task Force on El Salvador, Nov./Dec. 1980.

- Miami Herald, April 14, 1980.

- Washington Post, April 21, 1980.

- See for example, Guardian, March 26, 1980. Also according to Gramma, Weekly Review in English, Jan. 18, 1981. Honduras has more than 3,000 soldiers under the command of Colonel Danielo Carrera Suazo, and advised by 30 U.S. officers ready to go into action against the democratic revolutionary forces in El Salvador.

- “Dissent Paper on El Salvador in Central America—DOS 11-6- 80,” U.S. Dept. of State, pp. 2 and 8, (available from CISPES, P.O. Box 12056, Washington, D.C. 20005); Christian Science Monitor, Oct. 2, 1980.

- Miami Herald, May 17, 1980.

- Mexican Weekly, Processo, Aug. 18, 1980; Los Angeles Times, Oct. 10, 1980; and “Dissent Paper on EI Salvador in Central America—DOS I 1-6-80,” U.S. Dept. of State, pp. 15 and 17.