This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Alternatives for India: Western or Indigenous Science

by J. Bandyopadhyay & V. Shiva

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 2, March-April 1981, p. 22–28

J. Bandyopadhyay and V. Shiva are scientists working with the Indian Institute of Management in Banalore, India. They participated in a recent workshop on, “An Alternative Approach to the Management of Research, Development and Education in Science and Technology.”

While the voluminous documents say more and more about the invincibility of modern science and technology in tackling the human problems of poverty and unemployment, Indian people in larger numbers sink below the poverty line every day. The third largest scientific and technological workforce in the whole world, sitting amidst the most cruel poverty and stagnating social relations has been feeling strongly about the absurdity of its own existence. The huge modern scientific establishment that has been created in India is neither closer to self-reliance in its own activity, nor has it been able to break out of its social isolation from the deeper and broader realities of Indian life. This manpower plays no significant role in the modern industrial sector which more or less depends on imported technology for its survival and growth. The scientific and technological establishment has not made any positive contribution to the growth of the large traditional sector, a sector that is often invisible to the eyes of urban planners and intellectuals (in spite of the fact that it is the dominant technological mode covering sometimes as much as 85 percent of the population).1

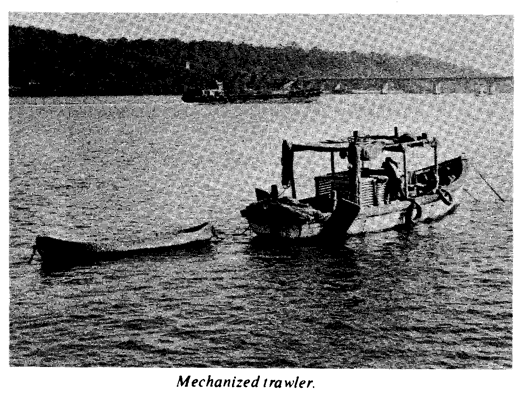

An attempt was recently made by concerned researchers and activists in a Workshop on “Alternatives in Science and Technology” held in Bangalore, India, to identify the historical roots and the present socio-political role of the establishment science and technology and to conceptualize the philosophical, political and economic base of an alternate framework for the development of science and technology that would be helpful to the Indian people.2 The discussions in the Workshop indicated that there are two significant ways in which the place of science and technology in India differs from their role in the industrially advanced countries. Firstly, the Institutions of Science and Technology and the Centers of research are not directly linked with productive activities in the Indian industrial sector. Secondly, while productive activities based on modern science and technology directly imported from the West are unable to properly substitute the traditional productive activities in terms of employment and ecological stability, they do, however, destroy them by wiping out their resource base. The conventional viewpoint on science and technology sees the present day Indian science and technology as ineffective because of factors like inadequate budget allocation, lack of proper management and the absence of an appropriate system to inculcate motivation and scientific values among Indian scientists.3 The discussions in the Workshop, however suggested that the problem in Indian science does not arise from ineffectiveness external to scientific activity, but from the very content of the activity. Indian scientists and technologists are, paradoxically, involved in an activity that is rooted and sustained in alien cultures and different environments, while at the same time subscribing to the myth of the universality of this science and technology. While scientists in India are channeled into these scientific traditions of advanced countries, the absence of a scientific community in India undermines their productivity both in terms of their intellectual contribution to that science and their technological contributions to the satisfaction of the needs of Indian society. There is no community of scientists in India because, on the one hand, individual scientists interact more with colleagues in the West than with colleagues within the country (sometimes in the same institutions), and on the other hand, Indian industry collaborates directly with foreign companies rather than with the Indian research and development establishment. There is thus a lack of coherence, within the scientific community, and between this community and industry which influences the health of the Science and Technology establishment in India per se, as well as its impact on society.4 Today what gets counted as “scientific” in India is the off-shoot of the tradition that was imported to India from the West in the 19th and 20th centuries. Parochial views of science which saw the scientific tradition of the West as universal and those of non-western cultures as particular, irrational, and superstitious led to the belief that scientific thought and activity was being introduced for the first time in India by the European colonisers. This view marginalized and made invisible the indigenous scientific and technological framework which had supported the Indian people successfully, not only by fulfilling the requirements of daily life but by capturing a good amount of the world market for manufactured commodities.5 The reason that more is not known about this phenomenon of de-industrialization of the Indian economy and destruction of traditional sciences and technologies has little to do with the intrinsic “irrationality” of the traditional world-views or the “inefficiency” of the traditional production systems.6 It is related more closely to the pervasive assumption (accepted as much by the Indian elites as by the Western ones) that the scientific tradition of the West is inherently most rational, and that the western technologies are the most efficient in an absolute sense independent of factor endowment and local resources. Further, domination of the non-western colonies by the imperialist nations has been explained on the grounds of this unquestionable superiority, instead of this assumed superiority being explained by first, military and later cultural domination. Thus for example, when health care was being planned in independent India, the obvious assumption seemed to be that there was a need for increased availability of the entire system of western medical science and technology, in spite of the historical existence and availability of systems of health care like Ayurveda7 and Yoga. The result was further destruction of these systems, a process which started mainly during the British rule. Today, a single Institute of Medical Sciences in the capital of India, mainly catering to the political and economic elites, has a budget equivalent to that of all the indigenous systems of medicine. While it might be fallacious to see deterministic links between budget allocations and productivity of scientific activity, it would also be idealistic to expect scientific systems to prosper with no resource base in material, sociological and intellectual terms. The destruction of the social systems of indigenous medicine was not the result of its inferior effectiveness in health care, which was never ascertained. A conclusive evaluation would be problematic anyway since the systems are framed on diverse philosophical bases. While the western allopathic systems might be more sophisticated, rational and efficient, when evaluated on merely analytic criteria, systems like Ayurveda and Yoga were, and continue to be, more sophisticated, rational and efficient when evaluated on the basis of holistic insights. Thus, while allopathic medicine might provide a finely structured diagnostic breakdown about cardiac problems, and might provide drugs for cure or quick relief (with all the side-effects that may not be desirable but are never part of the assessment of efficacy) it fails to provide the means of prevention of these problems. On the other hand, systems like Yoga, while not having the detailed analysis and categorization of the ailments, can, through its holistic approach, provide a preventive treatment for a range of health problems. Further, the modern system engenders centralized, multinational-dominated, capital-intensive and research-intensive facilities available only to a privileged minority. Traditional systems, on the other hand, are decentralized and to a large extent allow better control by individuals over their own health. Thus, the accepted superiority of the western health care system is found to be based only on a restricted set of evaluative criteria. On the basis of a more general set of criteria, neither its rationality nor its efficacy could be guaranteed. The fact that most scientists including medical scientists and technologists all over the world are practicing science and technology that originated in the West is in no way a confirmation of its uniqueness and universality on the level of rationality. Rather, it is an expression of the cultural domination of the advanced countries over the third world countries. Naive supporters of the universality of science and technology often raise certain irrelevant questions like “Do not Newton’s Laws hold good in India?” or “Does the earth rotate only in Europe, since Copernicus was a European?”. While a falling apple in China or India will be surely guided by Newton’s laws, a Britisher can also be cured by Acupuncture or Ayurveda. However, Newtonian mechanics and Acupuncture or Ayurveda were developed in completely isolated cultural contexts and had their own respective criteria of legitimization within the respective practicing communities. It is this element of science and technology which is not universal. 8 The myth of neutrality and universality of western science and technology has been retained and encouraged by the Indian elites long after political independence was achieved. Paradoxically, this has been with the proclaimed objective of decreasing dependence on foreign powers and multinationals, and removing poverty, inequality and unemployment. Development programs which claim to be for the upliftment of the people, have systematically, through the forceful introduction of alien technologies, led to further inpoverishment of the rural poor. Mechanized fishing was introduced by the Indian State in collaboration with agencies like the World Bank in the name of improving the status, i.e. the quality of life, of 6.5 million people living in the Indian fishing communities. The goal was improving the productivity of the sector, thus, also increasing the availability of fish for the protein-starved people of India. What has happened is just the reverse. The control of fishing is now in the hands of multinational corporations and mechanized fishing is a serious threat to the very existence of these fishing communities.9 Traditionally the fishing community of India has been satisfying the need for marine food of the entire coastal region. They have done so over the centuries, with their own techniques which were ecologically stable (the ecological stability is substantiated by the fact that traditional fishermen have not depleted the marine resources. This is in contrast with the collapse of fishing in Peru which resulted after few decades of reckless trawler fishing by the world’s leading fishing nations.) The gear, tackle and boats are made by these traditional communities with local raw materials and local skills. The preservation techniques are also labour intensive and self-sufficient. The modern technology packet of mechanized fishing, refrigeration and canning has drastically changed the occupational pattern of the fishing communities, and also the nature of the consumers. After the introduction of mechanized fishing, trawlers and purse seiners, the fraction of fish obtained through traditional techniques has come down from 84 percent to only 7 percent in only a few years.10 For the majority of the fishing community this has meant a great deterioration in their standard of living. Most of the traditional fishermen, for whom fish was a regular food until a few years back, now live only on starch like tapioca and consider fish a luxury that they cannot afford! In fact the fish that was available to the poor people through traditional techniques, now finds its way through refrigeration and canning to the affluent in India and abroad. Instead of improving the lot of the poor, the imported modern fishing technology is the vehicle of transfer of resources from the poor to the rich. The modernization strategy has also failed to build self-reliance or decrease dependence on multinationals. While the traditional fishing community did not depend on the Indian bureaucracy or foreign powers for its resources or markets, today fishing is controlled by large Indian business houses like Tatas and large multinationals like Union Carbide, Levers and Britania. Moreover, the purchase of trawlers and canning and refrigeration units have all increased technological dependence on foreign firms. The phenomenon of increasing centralized control of resources and markets, and increasing technological dependence is also found to be taking place in agriculture. This has happened in spite of the existence of ecologically viable and nutritionally adequate cropping patterns. In this sense the imported technologies were not socially neutral; and their use was neither inevitable nor the only choice for technological development. For instance, the technology of the green revolution was only one choice out of an entire range of technological possibilities and has given rise to new hybrid seeds that give high yields under specific conditions. Green revolution technology” was a choice not to start by developing seeds that were better able to withstand drought or pests. It was a choice not to concentrate first on improving traditional methods of increasing yields, such as mixed cropping. It was a choice not to develop technology that was productive, labor intensive, and independent of foreign input supply. It was a choice not to concentrate on reinforcing the balanced traditional diets of grains plus legumes.”11 Extracted from IFDA Dossier Dear Friends, Thank you, The myth of food shortages in India has been invoked to justify the import of the new agricultural technologies. However, it is interesting to note that “before World War II, Africa, Asia and Latin America were net exporters of food. Then countries such as India, Chile and the Soviet Union, traditionally grain exporters, became importers of massive quantities”.12 This shift from self-sufficiency to dependence has taken place in many subtle ways, one of them being the increased land use for growing cash crops. The new agricultural technologies have generated centralized, capital intensive and research intensive structures. For example, in traditional crops a farmer could keep aside part of the grain as seed, for if she/he uses the high-yielding varieties (HYV), she/he has to perpetually depend on centralized supplies. While earlier a farmer was dependent on locally available organic manure for fertilizer, for the HYVs she/he has to procure chemical fertilizers at high financial and ecological cost. The chemical fertilizer industry further increases national dependence on multinationals. Moreover, while on narrow criteria the green revolution technology has increased yields of certain crops (and today yields food surplus), it has failed to provide food to half the Indian population which lives below the poverty line and does not have the necessary purchasing power to buy food produced in a capitalist framework. Rashid Shaikh is a molecular biologist from India, and a fellow at Harvard. During 1972, he taught science to rural students of the Hoshangabad district in India.

Few Third World countries have emphasized the role of science and technology in development as has India. Indeed, the current Prime Minister, Mrs. Indira Gandhi, serves for all practical purposes as the minister for science and technology and views science and technology as a key to solving the problems of poverty and backwardness. Yet the government’s approach to technological development has not reached India’s poor, and has, in many cases, worsened their plight. With a total of 2.3 million, scientific and technological personnel, India today has the third largest workforce in the world (only the U.S. and U.S.S.R. are larger). This represents an approximately twelve fold increase since independence in 1947. The funds allocated for research and development (R and D) have seen a four-hundred fold increase: from Rs.11 million in 1948-49 to R.s 4.5 billion ($600 million U.S.) in 1976-77, and represents about 0.7% of the GNP. The government provides more than 80% of the R. and D. funds. Industrial production has risen at a fairly rapid pace, and India is the tenth largest industrial nation today. India has the best expertise in nuclear technology in the Third World. India manufactures computers, textile machinery, heavy engineering goods, pharmaceutical and fertilizer plants, tractors, automobiles, locomotives and other sophisticated industrial products. Yet, the Science and technology policy of the government has been a target of constant criticism. It has been argued that given the population and the problems, more funds should be made available for R. and D., perhaps as much as 2.5% of the G.N.P. Also, the major beneficiaries of public spending have been nuclear energy, defence and space; more support should be given to agricultural and medical research. The Indian paper to the United Nations Conference on Scientific and Technology Development (UNCSTD) admitted that “most Indian R. and D. agencies are much stronger in the generation of technology than in its delivery.” During the period 1953-75, Indian laboratories developed 1,923 processes, but in 1975 only 254 (15%) were being used in actual production. Thus, although India’s industrial sector has shown expansion, most of it has been based on technologies imported from the industrialized countries. In some cases, where know-how exists in India (e.g. construction of fertilizer plants, drilling for oil), the government has still preferred to import the technology. Moreover, scientific and technological personnel have been drawn from the urban middle and upper classes; and industrial production has been directed towards the urban, consumer, and export markets. The impact of this kind of policy on India’s poor is not difficult to fathom. The scientific and technological development has not helped most of the 80% of the population living in rural areas almost half of whom have practically no land and live below the poverty line. In fact their relative economic status has deteriorated. These consideration demonstrate the need for a different pattern of scientific and technological development for India. I will discuss two aspects of the problem: appropriate technology, and bringing science to people. Appropriate Technology Appropriate technology (A.T.) has come to mean technology which is decentralized, small in scale, labor intensive, amenable to mastery and maintenance by local people, and harmonious with local cultural and environmental conditions. Initially, there was a lot of enthusiasm for A.T. among scientists and engineers. Some of the fervor was lost during the half-hearted and ill-conceived campaign for A.T. during the Janata government (1977-79). More recently, Mrs. Gandhi’s government has taken a more critical position toward A.T., calling it a manoeuvre and a diversionary tactic by the West. But, many scientists and engineers still believe that A.T. should be given a lot more emphasis in India’s developmental plans. Bringing Science to People The Weltanschauung of the Indian people is a complex mixture of traditional wisdom and superstitions. To dispel some of the myths and superstitions and to expose people to the scientific notions of cause-and-effect, several attempts have been made recently at bringing science to people. One interesting effort is being made by the Science Education Group, based in Bombay, and run by a group of scientists and students. The group has organized several educational activities, but to date the most successful was a program to demystify the solar eclipse on February 16, 1980. Indian superstitions related to the eclipse tell people, among other things, to stay indoors, and not to eat during the eclipse. No attempt was made by the government, scientists, educationists or media to dispel these beliefs. The conflict between the two systems of production of food as mentioned above is not merely an academic issue related to relativistic criteria of rationality. It is an issue related directly to the survival of the people in the largest sectors of employment (in spite of massive industrialization in India, agriculture absorbs the maximum labor, followed by the handloom sector which is also facing a similar threat from mechanization). In the last few years, this conflict has taken the shape of mass movements in the coastal and agricultural areas, where for the majority of the people, capitalization of agriculture and fishing are a threat to their very survival (and unlike the advanced capitalist countries, the victims of capitalization in India are not even consoled with the benefits of unemployment insurance!). In India, hundreds have died and thousands have been arrested in fishermen’s and farmer’s revolts in the last few years. The repression might continue until the livelihood of entire communities is destroyed (with only the privileged minority in these communities being able to avail of the new capital intensive technologies). And after these communities have been wiped out the new systems will be projected as outcomes of a natural and rational pattern of progress! Support to the traditional systems of science and technology in the third world countries has often been attacked as a reactionary attempt to hold back the national progress and to go back in history. These attacks originate from vested interests as well as well-meaning radical groups. Movements to defend the traditional systems and to improve on them as alternatives in science and technology are not motivated from an utopian and nostalgic attempt to recreate the past. They are motivated, instead, by the recognition that these systems are a contemporary reality in India, that on the functioning of these “inefficient” systems depend the livelihood of the millions of poor Indians today, and a large scale displacement of these systems by “efficient” systems is a guaranteed way to pauperize these millions for whom these are the only technological modes available, either as consumers, or as producers.Alternatives in Science and Technology

INDIGENOUS SCIENCE VS. WESTERN SCIENCE

Health Care

Mechanization Has Led to Greater Poverty

Fate of Traditional Fishing Communities

Self Sufficiency Vs. Centralization

APPEAL FROM TRADITIONAL INDIAN FISHING COMMUNITIES

Sept.-Oct. 1980

The National Forum for Catamaran & Countryboat Fishermen’s Rights appeals to you and the concerned authorities of your country to take note of the distress of 6.5 million traditional fishermen of India and to take appropriate measures to alleviate our miseries.

In recent years, the coastal waters of the Indian Ocean, where we have been fishing most effectively for centuries through our traditional, labour-intensive and ecologically safe method of fishing, has been invaded by oversophisticated fishing trawlers and purse seiners. They have been recklessly scraping the seabed, resulting in depletion of fish resources and destruction of fish ecology. These trawlers and purseseiners, which were supposed to undertake deep-sea fishing, are shamelessly fishing in coastal waters, sometimes hardly 200 meters from the shore; thus driving away the fish from the coastal waters by the turbulence of the waters as well as destroying the valuable nets and boats of our fishermen, which has led to violent clashes in the sea between the mechanized boat-owners and our traditional fishermen, resulting in the loss of life.

The so-called ‘mechanization’ of our fishing industry has not really benefited the traditional fishermen. Fifty per cent of our fish lies in the coastal waters near our shores. Since 50 per cent of the prawn resources, which our country is exporting, is in these coastal waters, the mechanized trawlers and purseseiners, whose main interest is to catch prawns for export, will always tend to fish in these coastal waters, where our traditional fishermen fish, thus bringing untold misery to our fishermen. It is this craze to export prawns and fish at whatever cost, to foreign countries in order to earn foreign exchange, that has been the cause of our sufferings and hardships.

The burning of trawlers, destruction of fish nets and boats, violent clashes and the cutting of legs of our fishermen and purseseiners, charter smaller mechanized boats to fish in shallow waters and send their trucks around the Indian coast to collect the fish, then freeze and pack it under their label, export the fish, and then collect the deep-sea export cash incentives which should have gone to the smaller fishermen who caught the fish. In this process the deep-sea trawling business encourages the smaller trawlers to violate and deplete the shallow fishing grounds of our traditional fishermen. Besides, once the fish in the sea is over, as has happened in many over-fished countires, the few rich deep-sea fishing companies and businessmen will easily give up fishing as a profitable venture, whilst all that we may get is a few feet of earth to bury our dead.

The burning of trawlwers, destruction of fish nets and boats, violent clashes and the cutting of legs of our fishermen around the coast of India, provides grim evidence of the current economic genocide of the 6.5 million traditional fishermen now being committed by the trawler and purseseiner industry with the knowledge of our New Delhi planners.

We appeal to you therefore:

1. To stop the imports of prawns and other varieties of seafoods from our country by Germany, France. Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, Norway and other European countries.

2. To stop all aid to our country for the purchase of more trawlers and purseseiners, as there is an over-saturation of these vessels in our seas.

MATANHY SALDANHA

Chairman

175 South Avenue

New Delhi, 110011 IndiaAgricultural Technology

Commentary: Reflections on Appropriate Science in India

By Rashid Shaikh

Appropriate technology R. and D. thus remains an important area of concern for many scientists in India. However, some recent experiences have raised questions about the application of A.T., especially its interaction with the existing social structure. An example will illustrate this point.

In the Hoshangabad district of Central India, the ground water table is quite high, yet the traditional wells are expensive and inefficient. The traditional wells generally depend on seepage of water, are 10-20 feet in diameter, are lined with bricks, and are not very deep due to the cost. In the past decade, two voluntary agencies working towards rural development introduced a new method for well building. Prefabricated, reinforced cement rings, 5-10 feet in diameter were lowered in the ground as the well was dug. Using a diesel powered pump, water and mud were removed, and digging continued. By the time the well was 50-60 feet deep, an underground spring could generally be tapped, ensuring a continuous and plentiful supply of water. These wells cost about half as much as the traditional wells, and very rarely went dry in the summers. Over the years, a number of entrepreneurs in the area started manufacturing the rings, renting pumps, and training people for digging. The water was suitable for drinking as well as irrigation. It seemed to be A.T. at its best!

But problems soon accompanied the new wells. Typical of most of India, about half of the population in this area was composed of landless labor, and only about 15% of the land-owning farmers had enough land and credit to own a well. After several years of work, the agencies realized that as a result of their efforts, the better-off farmers now had a source of cheap water for irrigation, and were getting richer, leaving the poor peasants poorer.

This example, one of many, shows that innovations in A.T. alone cannot produce the development of the bottom-half, the have-nots. Their development depends also on a change in the pattern of social organization and structure.

A young student working at a rural science center found that a polyester film would protect the eyes from the glare of solar cookers. Further research showed this polyester film to be safe for viewing the eclipse. The Science Education Group then started a campaign, and distributed “Solar Goggles” (a strip of the film, stapled between two computer cards, some instructions and a message to join “the Peoples’ Science Movement”) for Rs. 1(15¢). They distributed 30,000 goggles, which was a small fraction of the total demand. The group also held a few demonstrations where people came in large numbers to watch the eclipse. Many participants broke the old taboo by eating during the eclipse, only to learn later that some well known scientists, who had gathered to study the eclipse, abstained from eating during the eclipse.

What will be the long term impact of watching the solar eclipse for people who for centuries have been frightened by them? Will the scientific attitude, learned during the discussions about the eclipse, go beyond the particular phenomenon, and affect other aspects of their lives? And despite the government’s position, where will the A.T. movement in India go? Will it lead to development or further the disparities in incomes? It is too early to know the answers to these questions. But one can see a hopeful sign today: India has a growing number of committed people – scientists, engineers, educators, students and other – who, after three decades of experimenting and observing, have learnt that for development of the country, working with that neglected majority is crucial.Community Response

The Importance of Traditional Technologies

Reaction to “modernisation” and westernisation by traditional producers cannot be interpreted as an irrational response to change. Technological change has been accepted by traditional communities irrespective of its country of origin when it does not threaten their existence. Weavers in India very effectively accepted the Jacquards, Dobbies and Fly Shuttles which got transferred from far away places like France and England. And the European nations had systematically absorbed sciences and technologies from the East. Cross cultural fertilization of ideas and improvement in modes of production have always taken place. The characteristic of contemporary technological change in India is that it is forced on the people without their conscious acceptance and it is a one way process leading to dependence, instead of fruitful interaction with the West.

The arguments in this paper need not be taken as an attack on everything from the West. It is rather an attack on the concept that everything from the West is more rational and efficient, that it is socially neutral and must be adopted for the progress of the Indian people. The case studies that have been discussed here focus on introduction of western science and technology which have restricted the possibilities for survival, let alone human development, for the vast majority of the Indian people. The traditional systems of science and technology offer a set of alternatives that are quickly vanishing. These systems need to be considered if a wider range of technological possibilities allowing human development based on social justice, economic well-being and ecological balance are to be created for the people of India.13>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 2 <<

REFERENCES

This dependence of a vast majority of third world populations on traditional technologies is slowly being recognised in works such as:

A. Nandy, The Traditions of Technology, Alternatives, Vol. IV, No.3, p. 371-385.

C. Alvares, Homo Faber: Technology and culture in India, China, and the West 1500-1972, Allied Publishers, New Delhi, 1979.

Rural Development: Whose Knowledge Counts, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 10, No.2, 1979.

The rationality of these systems is argued in: Y. Elkana. “The Distinctiveness and Universality of Science,” Minerva, 15, 1977.

B.R. Wilson, Rationality, Blackwell, 1974.

A brief commentary on the Workshop is available in I.F.D.A. Dossier 20, Nov.-Dec. 1980.

S. Dedyer, “Underdeveloped Science in Underdeveloped Countries”, Minerva 2, 1963, pp. 62-81.

J.A. Hobson, The Evolution of Modern Capitalism, Unwin, England, 1930.

herbs.

Similar work has also been reported from other countries. See Small Fishermen in ASEAN countries, IFDA Dossier 14 December 1979; Osamu Okada et. al. Fisheries in Asia, IFDA Dossier 14, December 1979.

S. Goonatilake “Technology as a Social Gene”: Examples from the Industrial and Agricultural Systems”, Paper read at Workshop.