This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Who’s at the Controls? Sanrizuka Farmers vs. the New Tokyo International Airport

by the editors of AMPO

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 10, No. 5, September/October 1978, p. 20–28

This article is abridged from the special issue on Sanrizuka of AMPO Japan-Asia Quarterly Review, Vol. 9 No.4. A year’s subscription to AMPO is US$12.00 for individuals and $20.00 for institutions, from AMPO, PO Box 5250, Tokyo International, Japan. AMPO is published in English.

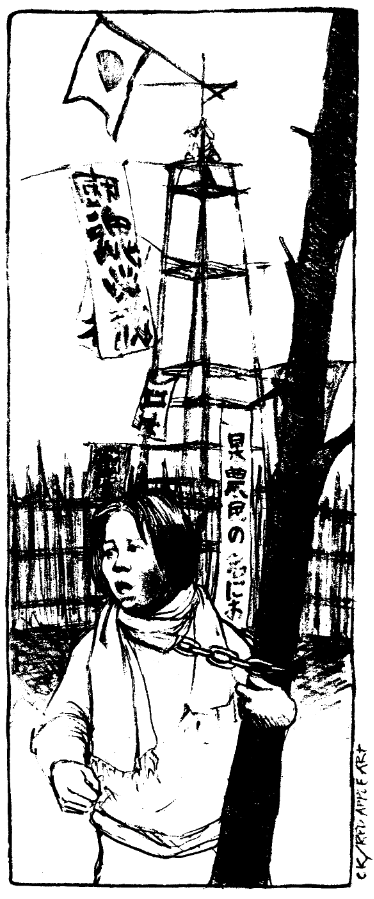

All photos printed here are by Fukushima Kikujiro, a militant free-lance photographer who has been with the peasants’ struggle from the very beginning. He has also covered numerous people’s struggles including those on atomic weapons, military affairs and the student movement.

Introduction

For twelve years the farmers of Sanrizuka have fought government demands to sacrifice their fields for a New Tokyo International Airport. Their determined resistance has evolved into a struggle of universal significance, challenging the mindless ethos of Japan’s frantic postwar industrialization. It has inspired people’s movements all over Japan and brought together the finest elements of radical labor, the Buraku (Japanese outcast) Liberation Movement, community struggles to resist industrial development and oppose pollution, consumer protection movements and farmers’ struggles to protect agriculture. In 1966 the Japanese government abruptly and arbitrarily decided that the Sanrizuka farmers’ land, 66 kilometers from Tokyo, should be confiscated to build a New Tokyo International Airport. The farmers were never consulted; they read the decision in the newspaper. The majority were enraged with this arbitrary decision and rose to protect the farms they had made fertile through painful years of labor.

But the government and its Airport Corporation responded violently with riot police and bundles of banknotes. In this confrontation the farmers had to risk their lives on the one hand and resist being bought off on the other. Supporting the farmers were radical students and workers whose own liberation struggles were in the midst of an upsurge, stimulated by the heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people against U.S. aggression.

Those who refused to sell their land, determined to remain farmers, were proud people. They despised the arrogance of Airport Corporation officials who callously treated farmers as though they lacked integrity, ready to bow and scrape to whomever offered them the biggest handout. But pride in themselves and their heritage runs deep, and the farmers quickly advanced from an early defensive posture of protecting their “private” farms to an entirely new and radical outlook. They developed penetrating insight into the anti-farmer, anti-people nature of state power.

The government claimed that the farmers should surrender their “private property” for the “public good,” that is, for the airport. But how is the public better served by the airport than by the farmers? What is “public” about an airport (or petrochemical complexes, steel mills and other giant industrial structures for that matter) catering to the interests of big corporations and built at the sacrifice of peaceful primary producers who feed the many? The farmers of Sanrizuka have radically challenged this perverse rationale of “development.” They have exposed this government, which tries to enforce such development with police violence, for what it is: the mouthpiece and protector of private interests.

The decline in the agricultural population and in farming families reflects the supremacy of urban corporate industry which, solidly backed by government strategy, has deliberately demolished rural communities to create cheap labor for their factories and construction of the infrastructure supporting industrialization. For example, the Agricultural Standard Law, instituted in 1961, was a legal device to accelerate this process of destroying agriculture. It imposed “structural reforms” on agriculture which in effect meant that only a thin layer of rich farmers would survive the impact of easing restrictions on agricultural imports.

Most farmers were forced to make a massive exodus to the cities to work there for half the year as construction workers or as seasonal workers in auto plants, steel mills, or in other odd jobs. The resulting margin of decrease in farm land, amounting to 1.1 million hectares (2.72 million acres), became factory sites, golf courses, leisure centers and other sites of urban luxury for the privileged. Confiscating land in Sanrizuka for the new airport is essentially part of this agriculture-scrapping strategy.

The new airport was specifically conceived as part of the government’s industrialization plan to turn the entire Hokuso Plateau, one of the richest farming areas in Japan, into an “industrial area” linked with the coastal petrochemical complex built at the sacrifice of local fishing.

Pure business speculation is yet another motive behind construction of the new airport. The airport neighborhood is being turned into a large commercial area with hotels, bars and other speculative enterprises mushrooming everywhere. Fortunately, the investors have yet to reap any profits. As Maeda Toshihiko, a peasant thinker, said, “The government should not have claimed the airport was for the public good; it should have frankly admitted that it was only to create new opportunities for profiteering.”

What has been the result of the strategy of industrial supremacy of which the New Tokyo International Airport is a part? From 1960 to 1975 Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate dropped from 90 per cent to 74 per cent, and its grain self-sufficiency rate dropped from 83 per cent to 43 per cent. Japan has become completely dependent upon foreign food sources, U.S. agribusiness in particular, for vital food supplies.

Destruction of agriculture is not unique to Japan. The same strategy has even more barbarous and cruel expressions in many Third World countries where peasants and fishermen are being violently driven from their land for the sake of “industrial development” promoted by foreign capital. Although the Japanese situation is different, the Sanrizuka farmers are fighting the same fight as their counterparts in the Third World.

As the farmers’ struggle advances, it becomes more and more consciously oriented toward creating an alternative course of development for Japanese society. Rejection of chemical fertilizer, collective ownership and building direct distribution links with urban consumers who support their struggle, represents a small but important revolution in agriculture.

Now the Sanrizuka struggle has entered a crucial stage. The Fukuda Cabinet, immediately after it was formed in January, 1977, declared that opening the Sanrizuka airport was a top priority political task. The government has since mustered all its strength to crush the farmers’ resistance. In May, 1977, the Cabiner, Airport Corporation, Chiba District Court, and police secretly conspired to attack the two iron towers the farmers had erected to thwart the takeoff of planes. In the ensuing clash Higashiyama Kaoru, a young, dedicated member of the support movement was killed, and the government declared that the new airport would be opened on March 30, 1978.1

State Power vs. The People

The soil in Sanrizuka is fertile. Watermelon, taro, peanuts and a host of other vegetables produced here are enjoyed throughout the country and known for their exceptional quality and taste. Until recently Sanrizuka was a peaceful village where the people lived in close harmony with the land, where farmers worked diligently and life had meaning.

The history of Sanrizuka is by no means old. Most of this area used to be an imperial pasture. Many of Sanrizuka’s farmers settled here only after the Second World War, although there are others who have been tilling land Inherited for generations. The settlers say that when they first came the whole area was covered with bamboo bushes and tree stumps. They dug out the roots and stumps piece by piece and leveled the land. After more than twenty years of backbreaking work, they finally reclaimed the fertile soil they have today. This is the history that has inspired the Sanrizuka farmers today to live by the slogan, “The land is the same as our lives!”

By the beginning of the 1960s Japan’s economy was moving into high gear. Crucial factors in this growth were Japan’s active support of the U.S. in the Vietnam War and the beginning of Japanese overseas investment, especially in Southeast Asia. With these developments the demand for air transportation grew, and Japanese industrialists began to feel a pressing need for a new international airport to replace the existing Haneda Airport, which they said was too congested. So in 1962 the government decided to build a New Tokyo International Airport. Several sites were proposed for the new airport. In the face of fierce local opposition, and for other reasons as well, the government’s choice changed swiftly from one locality to another.

Suddenly in June, 1966 the Sato Administration announced that the new airport would be built in Sanrizuka. The following month the Cabinet, completely ignoring local residents, officially sanctioned this plan. With this decision the New Tokyo International Airport Corporation was established and set April, 1971, as the date for opening the new airport. To the farmers in Sanrizuka the government’s unilateral action came as a complete surprise.

On June 28, 1966, immediately following the government’s announcement, 3,000 local residents of Sanrizuka and their supporters held a rally denouncing the decision. They formed the Sanrizuka Airport Opposition League, encompassing 560 households and about 1,500 members. Tomura Issaku, a dedicated Christian activist then 55 years of age, was chosen as chairman of the Opposition League.

On June 28, 1966, immediately following the government’s announcement, 3,000 local residents of Sanrizuka and their supporters held a rally denouncing the decision. They formed the Sanrizuka Airport Opposition League, encompassing 560 households and about 1,500 members. Tomura Issaku, a dedicated Christian activist then 55 years of age, was chosen as chairman of the Opposition League.

At its founding rally, the Opposition League adopted the following declaration:

To forcibly deprive us farmers of our land permeated with our sweat and blood,

To destroy our agriculture,

Further, by means of noise and other pollution to force the whole agrarian population of the Hokuso District into a situation where they cannot make a living by agriculture,

And the livelihood and education of residents in the vast neighboring area is disrupted:

This is a blatant policy of disregard for our human rights which we can never accept!

We participants in today’s rally declare that we will resolutely fight the Sato Government and the prefectural authority until they abandon their plan to build the Sanrizuka Airport.

With this declaration the Sanrizuka farmers began one of the most heroic struggles in the modern history of popular movements in Japan, a struggle now in its twelfth year.

Caught unprepared by the farmers’ stubborn resistance, the government and the Airport Corporation sought to undermine their spirit and destroy their resolve. Those who refused to sell their land “for the sake of the nation” the government tried to pressure with ever-larger sums of money. As a result, some farmers, though not in favor of the new airport, reluctantly agreed to sell their land. The tragic consequence was that the once peaceful village of Sanrizuka was split into two camps, those unconditionally opposed to the new airport versus those who agreed to sell their land.

Ironically, those farmers who thought they gained by selling their land for what seemed like huge sums of money in fact saw their lives fall apart. With their newly acquired wealth, many of these former farmers lost interest in working. They lived quite comfortably for a time on the money from their land, only to wake one morning and find themselves penniless. In contrast, the farmers of the Opposition League formed a close-knit community of mutual support.

Exasperated by its failure to persuade the opposition farmers to sell their land, on October 10, 1967, the government and the Airport Corporation called out 2,000 riot police to forcibly carry out land surveying in Sanrizuka. All members of the Opposition League, organized into groups such as the Old People’s Brigade, the Women’s Brigade, the Youth Brigade and the Children’s Brigade, joined to prevent the survey using solidarity shacks which they had built at various spots within the proposed airport site. Thus the people clashed head-on with state power. By the end of the day the Airport Corporation had succeeded in driving piles along the periphery of the airport site at only three of the eleven sites planned for the day.

Out of this initial clash, Sanrizuka became a focus for people’s struggles all over the nation. At this time workers and students, inspired by the heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people, discovered in the Sanrizuka struggle a focal point of the most fundamental conflicts in modern Japanese society, and they came to take part. Some of these committed students and workers built their own solidarity shacks in Sanrizuka and stayed there on a permanent basis, helping the farmers with their crops, learning from them and fighting at their side. From this there emerged a genuine community of struggle and solidarity among the farmers, workers and students.

The strength of this coalition grew until in February and March of 1968 the Opposition League, the National Anti-War Youth Workers’ Committee and the Student Movement were able to unite 10,000 demonstrators in a series of rallies. Following the rallies the demonstrators marched to the Narita office of the Airport Corporation, forcing their way past armed riot police. In the process hundreds were injured and about 500 were arrested. Through this kind of courageous struggle the Opposition League frustrated the Airport Corporation’s plan to open the airport by April, 1971.

The Fight for the Land

Three times in 1970, in February, May, and September the Opposition League blocked the authorities’ attempts to force their way into the land for surveying purposes. Faced with the farmers’ determined resistance, in December of 1970 the government resorted to the ultimate weapon at its disposal, the Special Land Expropriation Law which legalized confiscation of the farmers’ land.

The land to be expropriated was located in the northern part of the Phase 1 construction site where a 4,000 meter runway was to be constructed. A large number of students and workers rallied to support the farmers’ struggle against confiscation and built a tent village. The farmers dug underground tunnels, built seven wooden towers including one more than a dozen meters high named the Farmers Broadcasting Tower. The Broadcasting Tower served two purposes: surveilance over the enemy’s moves and broadcasting encouragement and warning to the farmers. Flying from the top of this tower was a flag with a rising sun stained black around its rim. Also hanging from the top was a large banner with the words, “We Oppose Land Confiscation in the Name of the Japanese Peasantry.”

Expropriation of the farmers’ land began on February 22. The Airport Corporation utilized a total of 18,000 man-days of riot police and more than 200 pieces of land-leveling machinery. Before the operation was undertaken, the Airport Corporation said boastfully, “The job will be completed in four hours.” The farmers, however, sustained a bitter struggle for 14 days, directly confronting the blatant violence of the state.

On February 22 and 23, the first two days of the encounter, the farmers and their supporters fought off riot police with showers of stones. On February 24 the Children’s Brigade clashed with the Airport Corporation’s guards. Early the next morning 3,000 riot police charged students and workers, who fought back using bamboo spears against riot shields. The riot police then used bulldozers to lead another assault on the farmers’ supporters. As the bulldozers approached, 150 members of the Opposition League threw themselves in front of the heavy vehicles shouting, “If you want to move ahead, it will be over our bodies!” That day 141 men and women were arrested.

Members of the Women’s Brigade bound themselves with thick iron chains to barricades and trees inside their forts, glaring at riot police outside. Members of the Old People’s Brigade fought by crawling into underground tunnels, braving the danger of a cave-in from the weight of bulldozers roaring around above them. Members of the Children’s Brigade boycotted school to join the line of battle.

As the struggle continued into March, many farmers lashed themselves high up in trees to resist the land confiscation. But almost without pausing for breath the Airport Corporation felled the trees one after another, totally disregarding the farmers in them.

For the huge “Solitary Pine of Komaino” it was no different. A thickly bearded farmer and his neighbour resisted from inside a shack built in the tree, using yam hoes as spears. While bulldozers roared around its base, a crane looped a cable around the tree. At the same time water cannons deluged the farmers’ shack, shaking it violently.

From their position the farmers shouted down, “Will you execute us simply because we want to continue farming our land? We have climbed this tree prepared for death, and we will fight to out last breath!”

A chain saw roared, and as the cable tightened the huge pine trembled. The next moment the base of the tree soared high into the air, and the top came crashing to the ground. The two farmers were badly injured, but the police took them away without treatment.

It was 2 o’clock in the afternoon of March 6. With the felling of “the Solitary Pine of Komaino” the Airport Corporation declared that the first land expropriation had been completed. Throughout the preceding 13-day battle as many as 1,000 farmers and their supporters were injured and 401 were arrested.

The farmers’ spirit, however, was not broken. They crawled inside their underground tunnels and kept on fighting. Farmers in the Broadcasting Tower that was brought down in July of that year continued broadcasting as it toppled: “Even if this tower is pulled down, the spirit of us farmers will not die. We will build a second and a third farmers’ tower after this one!”

In September, 1971, the riot police started another offensive, the second compulsory land expropriation. Early on the morning of September 16, a band of guerrillas attacked a troop of riot police engaged in a search in the eastern part of Sanrizuka. Three policemen were killed.

The police retaliated with outright attacks on the three forts. In this confrontation 3,500 men and women of the Opposition League faced 5,500 riot police and 130 heavy vehicles like bulldozers, power shovels and cranes. The Komaino Fort put up fierce resistance. As the autumn sky was all but blotted out by torrents from a water cannon aimed at the fort, a power shovel, surrounded by riot police, roared ahead. From a tower in the fort the resisters attacked with a shower of Molotov cocktails. The machine burst into flame, and the driver leapt from his seat and fled.

As the battle ebbed and flowed, the police tightened their encirclement. At three o’clock in the afternoon, using a crane and cables, they toppled the tower that rose 20 meters above Fort Komaino, bringing it to the ground in a sea of fire. Of the dozen farmers and students who fell with it, one student was critically injured, his lungs seared from inhaling flames and his body bruised and burned all over. The police took him to the compound of the Airport Corporation office and left him there without treatment. That day 476 men and women were arrested.

Four days later the riot police attacked the last plot of private land remaining in the Phase 1 construction site, the residence of 65 year old Ohki Yone. They came while she was working in her yard. Her tiny house of two tsubo (6.6 square meters) was smashed in a moment. When Ms. Ohki resisted, six burly policemen knocked her down and beat her. With her head bleeding they threw her on a huge riot shield and carried her off.

The government used the deaths of the three policemen to bring new pressure on the Opposition League. In a much publicized campaign claiming to be hunting for outlawed murderers, they arrested 130 members of the Opposition League and supportive groups, including most of the members of the Youth Brigade.

These government efforts to break the farmers’ spirit only fired their opposition all the more, solidifying their determination to raise the Tall Iron Tower of Iwayama.

The Children of Sanrizuka

In August, 1967, a Children’s Brigade was formed within the Opposition League. At first about forty elementary and junior-high school students, children of League members, joined, but the membership gradually increased. During the fight against forced surveying of the farmers’ land by the Airport Corporation in February, 1970, the children boycotted school and joined their parents in the opposition. On February 24, 1971, the day of the first attempt to expropriate farmers’ land, children fought in the front lines against riot police and Airport Corporation guards. In that battle the guards clubbed and kicked them. About thirty people were pushed off a high embankment.

The news media criticized the Opposition League for “involving children in the fighting.” The best refutation of this criticism is the statement by the Children’s Brigade at the time of the first expropriation:

The Airport Corporation has brought guards and police with clubs and shields to steal our land. We don’t want them to turn our Narita into a military airport. Because school is important to us,

Because we want to study,

Because our lives are important to us,

Because our land is important to us,

we are fighting the guards who club us and drag us out of the tunnels. The tricks of the Airport Corporation will not defeat us. We will join our families and fight with them until victory is won.

The Children’s Brigade set up their own study program, taught by university students who had come to Sanrizuka to join the struggle. But the best education for the children was watching their parents fighting for their lives, and joining them in that fight. As the coming generation, the children who were fighting at Sanrizuka were getting something that they could never get from an education that aims only at scoring high grades.

After the Towers Fell

The Opposition League, undaunted by the two expropriations and the repression that followed the deaths of the three policemen, began to build a new stronghold, the iron tower. In March, 1972, Iwayama Tower, 62 meters high, was completed. It stood in the path of planes using the 4000-meter runway finished in April of that year. Along with a smaller tower, 31 meters high, which had been finished in May, 1971, it prevented planes from taking off and landing. Soaring high into the air, the towers kept the airport from being opened as the battle entered its eleventh year.

In January, 1977, at his first Cabinet meeting of the year, Prime Minister Fukuda insisted that the airport would be opened “within the year,” whatever the cost. Three prime ministers have come and gone since Sanrizuka was picked as the airport site. But those eleven years saw the Opposition League’s fighting spirit become ever more firmly rooted. Sanrizuka had become a symbol of opposition to the state. To use a Buddhist term, it was the “head temple” of the struggle for all Japanese people – a base not only for the farmers but also for victims of Minamata mercury-poisoning sickness*, the movements against pollution, nuclear power, and industrial development. The Fukuda Cabinet hoped to suppress all these opposition movements by using the full power of the state to demolish the towers and open the airport.

On April 17, 1977, supporters of the Opposition League held a rally at Sanrizuka with the slogan, “Defend the Towers- Abolish the Airport!” No fewer than 23,000 activists from opposition fronts throughout the country, the largest number to gather in the history of the Sanrizuka fight showed the authorities that a national movement to defend the towers was building.

Already more than 100,000 people had joined as legal owners of the towers, a movement promoted by the Opposition League to make the towers the property of all the nation’s people.

The national authorities gave up trying to remove the towers by frontal attack and resorted to a more underhanded strategy. On May 6 at three o’clock in the morning, 1,500 riot police quietly surounded the towers. They severed telephone lines to the outside, cutting off communication. At eleven o’clock, they attached cables to the towers, burned through their bases with acetylene torches and quickly pulled them down. Thus the towers were demolished by surprise attack with complete disregard for the law.

The day after the towers were demolished, the government made a flight test of the runway with a YS11 plane. On the ground, the Opposition League tried to stop the test by burning old tires to make a smoke screen.

Two days later 3,700 people, enraged by this foul play, gathered at Sanrizuka to hold a protest rally. Using stones, Molotov cocktails, and the poles of their banners they clashed with police. The police retaliated by firing tear gas cannisters at random.

Chairman Tomura expressed the Opposition League’s determination to continue fighting in a speech: “The state itself has violated the law by demolishing the towers like a thief in the night. We cannot restrain ourselves any longer in the face of this illegal government action. We will fight to the end, using any means necessary to force them to give up the airport!”

Indeed, the opposition forces then began guerrilla warfare, setting fire to police boxes in Narita City and to Airport Corporation buildings. A fierce, bloody fight developed in which one policeman was killed.

Final plans for the new airport call for three runways and a total area of 1,065 hectares (2,631.6 acres). Only Runway A of the three runways has been completed, and the corporation has yet to confiscate the land for the remaining 2,500 meter and 3,200 meter runways planned for Phase II of the construction. It took the corporation two violent, protracted campaigns to secure 550 hectares (1,359 acres) for the present runway. (Even at that, three tracts of land owned by two families within the Phase I construction site remain to be confiscated.) It took until April, 1972, to complete the first runway, and the terminal buildings and other facilities took until April, 1974. Phase II of the construction, still on the drawing boards, will require an additional 515 hectares (1,272.5 acres) of farm land on which 21 families belonging to the Opposition League continue to hold out, cultivating their farms in defiance of the government.

For five years after Phase I of the construction was completed, the airport was left untouched, a “flightless airport.” Cracks developed in its only runway, and the equipment in the airport buildings remained covered with dust. But the Fukuda Cabinet, having demolished the two iron towers in May, 1976, is frantically preparing for the opening of the airport. Because of the farmers’ determined resistance, the government’s original date for opening the airport (April, 1971) has been postponed six times. At the beginning of 1977 Fukuda declared the airport would be opened by the end of the year, but once more the farmers have forced the date to be pushed back, this time to the end of March, 1978.

Even if the government declares the airport legally open, one new problem after another will cripple it. For one thing, an airport is such a vulnerable system that the government has no way to protect its many vital parts from “guerrilla” attacks. In fact, since the towers fell, anonymous groups have attacked a number of vital facilities, burning some and completely destroying others.

Jet fuel is another headache. A plan to pipe in fuel was scrapped because of local opposition. An alternate three-year interim plan to use railroad tank cars is threatened by the Engineers’ Union of the Japan National Railways. They have declared they will strike if the railroad is used to transport fuel. The militant Chiba chapter of the union, in particular, will oppose any order to transport fuel.

Many other problems remain unsolved, such as transportation between the airport and Tokyo, and jet noise.2 If the airport is opened as planned at the end of March, 1978, there will be terrible traffic jams on routes connecting the airport to Tokyo, especially in Narita City. Passengers taking the four-hour flight from Hong-kong may face another four-hour trip from the airport to Tokyo once they arrive.

To make matters worse, the airport itself is defective. Because of their overriding political preoccupation, the Airport Corporation neglected to requisition sufficient land for Phase II of the construction. Although Runway A is officially 4,000 meters long, in fact, for arriving planes it is only 3,250 meters long. As a result jets must go into a steep climb after take-off and a corresponding dive when approaching. Japanese pilots have delivered a letter of warning that if the airport is opened as it is, they cannot guarantee the safety of their passengers.

With only one main runway complete, the airport cannot function normally. In an area where cross winds of 6-7 meters/second are common, an airport without an alternate runway is frequently forced to close down. As an airline expert pointed out, “An airport with only one runway is like a two-engine plane with one engine stopped.”

Politics is behind the Fukuda Cabinet’s relentless push ahead with this utterly defective airport. The government knows the airport cannot function properly even if it is opened. Nevertheless, its main goal is to crush the recalcitrant farmers and their supporters. In the government’s eyes this would break the back of militant people’s movements throughout Japan.

To this end a colossal sum of money, estimated at US $4 billion has already been invested in the airport. The Airport Corporation alone has spent $960 million including $184 million wasted on interest payments. To complete the airport the government will spend another $8 billion in a way reminiscent of the U.S. government’s squandering its people’s tax dollars on the Vietnam War. And like the Vietnam War, the more money the Japanese government spends to escalate its anti-people operation, the more enemies it creates and the more obstacles it invites .

The Sanrizuka struggle is not coming to a close. On the contrary, it is gaining new life, regardless of whether or not the government succeeds in declaring the airport open.

Since the beginning of 1977 the anti-airport struggle has rapidly expanded in scope, enlisting the fresh support of anti-pollution, anti-nuclear power and anti-“regional development” movements all over the country, as well as the Buraku (Japanese outcast) Liberation Movement. In addition, increasing numbers of workers have joined the struggle, among them the militant Chiba chapter of the Japan National Railway Engineers’ Union. Workshops, schools and local community groups are organizing a national support network for the Sanrizuka struggle.

For 22 days, beginning on September 18, 1977, people from all over the country marched 700 kilometers from Osaka through Tokyo to Sanrizuka to express their solidarity with the farmers’ struggle. Wherever the marchers went, local people welcomed them warmly. The marchers called this a “Long March,” spreading the seeds of the struggle all over Japan. When they arrived in Sanrizuka on October 9. more than 20,000 people from all parts of the country joined them for a militant demonstration.

Solidarity has been expressed not only in Japan but also in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world where people are fighting for their liberation. Thousands of people from both Japan and overseas, ready to fight alongside the farmers, have visited the Worker-Peasant Unity Hut at Sanrizuka, built in May of 1977 as a hostel, school and fighting post.

*****

Update

On March 26, 1978, a bold offensive destroyed air-traffic-control equipment thwarting the twelfth attempt to open the airport in twelve years. On May 20, the day of the opening, underground cables were expertly cut disrupting air traffic all over Japan. This resistance was led by the Chakaku-ha (Core Faction), the extreme leftwing group that was a center of violent student opposition to the Vietnam War in the sixties. Narita is now in operation, serving planeloads of passengers who are mostly businessmen and tourists feeding into Japan’s tumorous industrial, and possibly military, growth. The complete transformation of Japanese culture from one of agriculture to one of industry is destroying the “intricate interweaving of tradition and mechanization, craft and science.”3 It is clear however, that 13,000 riot police and $13M worth of fences will not prevent farmers and supporters from fighting for what is theirs.