This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Social Science Research: A Tool of Counterinsurgency

by Carol Cina

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 2, March 1976, p. 34–44

Today, there would be little research in U.S. universities without federal support.1 But this was not always so. It started small, in the last decades of the last century, when the process of adapting a social-control strategy from the United States’ then-imperial rival, Germany, was begun here.

Bismarck’s 19th century Germany boiled with class struggle: rapid industrialization, with repeated recessions, led to the organizing of working people’s associations which were often avowedly socialist. Guns and soldiers suppressed the uprisings of working people, and a national program of state-directed reforms was initiated to make life more bearable for them so that rebellions would not re-emerge once existing organizations were smashed. The reform program was called Sozialpolitik (social policy), and was developed in its modern form by a group of German social scientists2 as a nonsocialist answer to the popular demands for social justice advanced in theoretical form by Marx and Engels.

It was Prussian tradition for prestigious professors to work in the government, using their academic skills to help solve the practical problems of administering society. Many of their students were young intellectuals of the American bourgeoisie who recognized that the organization of the Bismarckian welfare state was a reasonable model for the United States, where industrial conditions were substantially similar to those of Germany. The U.S. Civil War had cleared away various political impediments to an industrialized economy dominated by Northern capital, and the political ideology of laissez faire individualism suited the rapid accumulation of capital into more and more centralized holdings. But as the control of entire sectors of the U.S. economy by a relative handful of corporations became greater, the ideology and practice of laissez faire became less useful. It made the natives too unruly; the higher, more monopolistic, stage of development of industry created the need for a more orderly integration of the country’s population into a system dominated by the largest business interests. It was bad for industry that there should be such labor struggles as had been raging for decades; it was downright inefficient. Just as bad or maybe even worse, an influential part of the ideology of that struggle challenged the overall power relations in capitalist society: socialism as a possible solution to the human strains that capitalism created had significant organized support among American working people in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, just as it did in the European countries from which they had emigrated.

The historical problem on both continents was due to the capitalist system of organizing human work: it separates control of the social wealth from those who produce that wealth. Since privately controlled distribution of the socially produced wealth is inequitable, social struggle is inevitable. The bourgeoisie’s principal response to this social struggle has historically always been to try mightily to exterminate it by whatever means necessary. Sozialpolitik and the corporate liberalism 3 which was its North American counterpart were clearly preferable to violent repression, though of course these “enlightened strategies” did not rule out more brutal tactics, as is clear from the study of American history.

The American students in Germany4 imported this strategy when they returned home, and in 1885 they founded the American Economics Association, where Adam Smith’s laissez faire theory, which barred the government from interfering with the economy, was supplanted by the German school built around the principles of economic and social-policy planning on a national level. The new way to handle social struggle was prevention, accomplished through the application of scientific analysis to the administration of capitalism’s institutions. It was the Progressive Era in the United States, complete with the Pragmatic Faith,5 the orientation to social control which posited that the intellectual labors of science and technology could uncover the pertinent facts, which an efficient government could then use to make policy which would solve the social ills of capitalism. It was the dawning of the corporate liberalism of the early 20th century—the vision of a reformable capitalism within the domination of the even-then giant corporations. Labor was to be brought into partnership with capital and the spectre of socialism laid to rest.

The problem was framed in terms of attempting to eliminate social injustice through raising labor’s productivity, thereby raising the amount in labor’s slice without having to change its proportional size. But the size of the whole pie could only be increased with the cooperation of the labor force. And co-operation on such a scale meant among other things social engineering of a sort—the conscious use of scientific techniques to formulate social policy.

It was within this configuration of practice and theory that responsibility for organizing academic social science began to be assigned to government. The task of applying scholarship to the problems of administering 20th century corporate capitalism was formally institutionalized in the United States with the creation of the first policy-research organizations: the Institute for Government Research (which later became the Brookings Institute), the National Industrial Conference Board, the National Bureau of Economic Research, and the Twentieth Century Fund. All were organized in the five-year period surrounding World War I. These liberal policy-research organizations were to supply the facts of the workings of the country’s political economy; they would be doing “social science that would admit of conclusions not influenced by the social ends of classes.”6 It was to be the ultimate answer to the socialist rabble-rousers; it was science, therefore it was fair. And it would make capitalism good for humans.

The first proof of the pudding arrived as World War I materialized amidst the pollyanna visions of partnership between labor and capital. Again, a piece of Germany’s social-management strategy was imported and laid onto the foundation of collaboration between business, academia and government which had hardly set. This was the practice of centralized organization of science work.

In the U.S., the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) had been chartered by Congress during the Civil War to advise the Northern government on science matters. It was the first use in this country of orderly access to scientific work as a military weapon, but productive forces had not yet developed to the stage where a separate administrative apparatus was necessary to integrate intellectual work and production. By 1916 that stage had arrived, because a shooting war with Germany meant the abrupt cut-off of the German piece of the international capitalist economy. German science and technology, on which a certain amount of the U.S. economy depended, became unavailable. At the same time, the threat of an impending trade war with Germany necessitated the rapid development of the United States’ own technical capacity.7 It was perhaps a bit like the situation in China in 1960 when the Soviet Union recalled its technical experts; it became immediately necessary to organize the intellectual work capabilities of one’s own population.

It was at this time that the National Academy of Sciences was called upon by Wilson to expand into directly organizing the scientific resources of the U.S. In his executive order, Wilson stated that “true preparedness” would result from the application of science not to military problems only, but to all areas of industry as well as to the advancement of knowledge without immediate practical significance.8 Out of this grew the National Research Council (NRC), a federation of research laboratories9 supported by the Carnegie Corporation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Engineering Foundation, the U.S. War Department and the Council of National Defense.10 Its financial support came from the accounting ledgers of the class which owned the means of production in the United States; such members of that class as George Eastman, E.H. Gary, A.W. Mellon, Pierre S. DuPont, and Ambrose Swasey (Engineering Foundation) personally participated in its operations through a system of advisory committees to the Council’s thirteen divisions.11

The divisions of the NRC were “constituted of the representatives of the leading national societies in . . . [various scientific] subjects”12 plus representatives from universities, research foundations and industrial laboratories. Representatives of the government were appointed by the President and included “heads of the scientific and technical bureaus of the Army and Navy and the civil departments . . . “13

During the war, the NRC set up research committees in most of the country’s universities “to concentrate the research capacity of these institutions upon scientific problems of war work”.14 Those committees were not dismantled, however, with the end of the war. The organizational net we move about in nowadays whenever we do physical or social science research is descended from the early NRC and takes from it its basic form. Unlike the honorific NAS, the NRC existed to organize the research work which had just achieved full recognition as the substrate of the technological base of U.S. power. With the end of the war the NRC was made a permanent institution by executive order of President Wilson, and was assigned the overall responsibility of determining the extent of research capability in the U.S. and Europe and then figuring out which fields could be developed through organized effort.15

Eerily, it was the Army and the Navy Intelligence Services which did the surveying of research in various parts of the world and the disseminating of the information collected to all appropriate government and scientific agencies.16 It is, after all, the military arm of the government which has to secure the territory exploited by business corporations; the military’s technological needs are deep, and its access to the intellectual workforce must be direct. The military also has a desirable management characteristic: a far-flung network under centralized control. It is a consistent fact of U.S. history that war has been the energy of organization in science — as the reader will presently see in the case of social science. It therefore follows that the military should itself see to the generation of that science work deemed necessary for its mission.

During the inter-World War period, the use of academic work in governing came to be accepted as indispensible.17 For example, a series of social science studies commissioned by President Herbert Hoover and carried out during the 1920s and 1930s both by the existing policy-research organizations and by special government advisory committees was, according to a government report, supposed to give

a complete, impartial examination of the facts . . . to help all of us to see where social stresses are occurring and where major efforts should be undertaken to deal with them constructively . . . The means of social control is social discovery and the wider adoption of new knowledge.18

Social control through social discovery meant the “organization of social intelligence”19 to manage society-wide problems. This necessitated a conscious strategy for organizing intellectual workers; since the main body of the intellectual workforce is in academia, that required the systematic organizing of academic workers to do whatever work was at any given time deemed necessary.

Accordingly, a government study entitled Research — A National Resource 20 noted that organizing strategy since World War I had proceeded through “decentralization of research activities by governmental agencies and centralization of research workers through the organization of national councils,”21 and recommended the expansion of the contracting-out system as the line of development most likely to yield the desired results. The national councils referred to were the National Academy of Sciences, the National Research Council, the Social Science Research Council, the American Council on Education, and the American Council of Learned Societies. They were intermediaries between those who determined research content and those who exercised their academic freedom by choosing to do the work so determined. The contracting-out system which they had begun administering came fully into bloom under the military administration of research during World War II, when policy set in the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) relied on contractual arrangements with university-based organizations to do the actual wartime research and development.22 This method of contractual arrangements was simply continued after the war, and OSRD’s central laboratories were developed into research centers operated by civilians under civilian management, but funded by the military.23

With the official declaration of World War II, the United States entered a 34-year war which had its official termination April 30 of last year.24 Consequently, both physical and social sciences have been heavily organized by the military arm of government with a continuity not achieved before the post-World War II period. The Southeast Asia War began the same year World War II ended,25 with its Korean War phase beginning in 1950.26 That was also the year of the first U.S. Military Advisory Assistance Group’s arrival in Viet Nam, and the year following the October 1949 victory of the revolutionary movement in China. European-style colonialism could no longer be sustained in that part of the world; it was routed by the power of people’s war. From the point of view of U.S. strategists, the new enemy was “insurgency,” and a novel weaponry was soon to be developed to counter it. Social science work was to play a key part in the production of the counterinsurgency technology of the 1960s and 1970s.

Social Science for Counterinsurgency

The counterinsurgency part of the story begins with the Office of Research and Inventions (ORI), successor to the wartime OSRD. ORI was established in May 1945 for purposes of “retention of the best scientific minds for the Navy team”27 so that the U.S. could develop capability in science areas “which were formerly European monopolies. For future emergencies, it was necessary to be self-sufficient in all fields of science.”28 ORI was to administer the principal federal financing for basic research in the physical and social sciences, mainly through contracts with universities, of course, until some other arrangement could be devised whose appearance was more consonant with the doctrine of academic freedom. Congress changed ORI’s name to the Office of Naval Research (ONR) in 1946 and assigned it the responsibility to support “basic research in the many scientific fields of interest to the Navy.”29 Even though the National Science Foundation was put together in 1950 to handle basic research exclusively, it has in no year (since figures on research expenditures have become publically available) exceeded the Department of Defense’s (DOD) expenditures for basic research in the social sciences.30 And within the DOD, it has been the ONR which has supported the research on human behavior which has been germinal to counterinsurgency social science.

Normal man . . . is the pivotal point of ONR ‘s research in human resources . . . The problem is to gain a more complete understanding of normal man’s relation to man, to a group, to supervision, and to the machines he operates . . . The human relations program is aimed at knowing more about the basic determinants of group behavior. ONR psychologists are seeking to find the relationship of human perception, values, ideas, and motivations to behavioral outcomes. 31

And indeed, the social science work which resulted from the Navy’s organizing effort is the founding body of work in the main tradition of social psychology: the study of the small group.

The Navy organized the work by having an advisory panel of prominent academicians in the relevant fields 32 review the research proposals in the behavioral sciences and recommend research programs and funding “that will most effectively serve the fundamental interests of the Navy”33 in five specific areas: (1) comparative study of cultures, (2) structure and function of groups, (3) communication of ideas, policies, and values, (4) the nature of leadership, and (5) growth and development of the individual. Five years after its inception, an organizing conference was held in which work done in the program between 1945 and 1950 was detailed in one place in public for the first time. It was hoped that publication of the conference proceedings in the form of a book called Groups, Leadership, and Men would “have some impact in shaping research in the social sciences elsewhere by setting forth our strengths and weaknesses in these various projects.”34 The various projects included much of the classic work in social psychology which graduate students must study to become knowledgeable in the field: Raymond Cattell on morale and leadership measurement; Leon Festinger on informal communication in small groups; John French on group productivity; Solomon Asch on the effects of group pressure on judgments, David McClelland on achievement motivation.

Here we have the height of academic freedom. The ONR maintained a “network of contracts with universities, research laboratories, and industrial institutions . . . [to generate] fundamental studies in science.”35 Proposals usually originated with the contracting scientists, were evaluated by the ONR, and if accepted, “the contractor is given almost a free rein in completing the study.”36 The academic worker’s freedom to do the jobs the ruling class needs done is the working class person’s freedom of choice to starve if working in the ruling class’ industrial or any other sector is repugnant. There seems to be something about the freedom of academia that conceals from view the consideration that “ultimately the basic research must be translated to a form of social technology with reasonable utility.”37 For the control of whom? By whom? Who consumes the products of the academic’s intellectual labor? Consumption is claimed to be uncontrolled, as if the product were purveyed on supermarket shelves alongside ITT’s Wonder Bread. It is said to be unfortunate that sometimes a customer full of evil comes along and bends the work to evil purposes, but that’s the price of having an intellectual work marketplace, which we all agree is the free way to do business. Compared with the social relations of production between serfs and landlords in medieval Europe, the marketplace type of commercial relation was named “free”. “Free” is an historical label which denotes a specific relationship of production characteristic of the capitalist mode of production; we are free to sell our capacity to work instead of having it bound to the use of a specific landlord. Broadly speaking, only that research work appears on the marketplace which ruling-class sources have determined should be done. So the problem is not an occasional evil consumer at all, but rather that the content of research work overall is determined; by the class which owns the wealth of the society.

As the ONR was temporarily carrying much of the administration of academic social science for the military, the Secretaries of War and of the Navy ordered Vannevar Bush, an electrical engineer who had been involved in the development of radar and in the Manhattan Project, to reorganize the government’s methods for getting science work done. On the basis of his experience as director of the wartime OSRD, Bush had authored Science: The Endless Frontier,38 the government’s official postwar document calling for extension of government organization of science work. When the National Security Act of 1947 (which brought into being the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, and the Defense Research and Development Board) was enacted into law, the Defense Research and Development Board was established on the lines worked out by Bush.

The Board’s mission included the preparation of an integrated military research and development program, rendering advice on trends in scientific research of relevance to national defense, and recommending measures of interservice coordination and allocation of responsibilities. 39

The bureaucracy set up in the Board consisted of sixteen committees, whose members were principally military personnel from the three services. One of them was the Committee on Human Resources, whose business it was to “establish a defense-wide social science research program.”40 Each Committee did its work through a series of panels of government and nongovernmental scientists who rendered their expert judgment on the scientific work to be undertaken. Panels in human resources included personnel, human relations and morale, human engineering, manpower, training, and psychological warfare.

The Board’s work resulted in the proliferation of military institutions for the organization of the intellectual work of social scientists. Before the 1940s were over, the Air Force had set up the RAND (Research ANd Development) Corporation and three other research establishments: the Human Resources Research Center, Laboratory, and Institute. They and the Army’s Operations Research Office (ORO) at Johns Hopkins University (set up in 1948) and its Human Resources Research Office (HumRRO) at George Washington University (set up in 1951), together carried out most of the military’s on-site social science research in Korea during the 1950–1954 war there. Studies were done there on psychological warfare, prisoners of war, racial integration in the Army, and various aspects of human behavior under combat conditions. Soon to become a hotbed of social science counterinsurgency, HumRRO would be an explicit target of the U.S. antiwar movement.

Meanwhile, in 1950 the first U.S. military units were landing in Viet Nam to advance the perimeter of U.S. client states. Their adversaries were fighting guerrilla war. During World War II the British had been the experts in counterinsurgency. Perhaps this was one of the European monopolies the U.S. wanted to break after World War II. Both the Korean War and the French-American Indochina War officially began in 1950 and officially ended in 1954. The conference convened in Geneva to write a treaty for the former ended up writing a treaty for the latter. The two wars taught the U.S. military two lessons: Korea demonstrated that U.S. atomic power was useless in a land war; Viet Nam showed that conventional military techniques would not hold empire territory against people’s war. Together, these combat experiences resulted in the development of a new strategic conception, a transition from the massive-retaliation strategy of the Eisenhower-Dulles period to the limited-war strategy of the Kennedy et al. period.41 It was at this time that the organization of the intellectual workforce for the production of a counterinsurgency technology had its quiet beginnings in the U.S.

The 1947 Defense Research and Development Board was the first centralized postwar body for physical and social science research planning for the military. Since 1958, this board, which is the conceptual heir of the wartime OSRD, has had a central military science (both social and physical) planning body called the Directorate of Defense Research and Engineering (DDRE). It was the DDRE which headed the apparatus which produced the infamous Project CAMELOT.

Development of Project CAMELOT

The DDRE “initiated a series of studies on the state of psychology and the social sciences in the defense establishment.” These studies were completed in 1959 by a Smithsonian Institution research group headed by Charles W. Bray, formerly of the Applied Psychology Panel of the National Research Council during World War II and later the Director of the Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center.

The research group had a steering committee and a series of task panels whose members came from a wide range of academic institutions and had considerable experience in government, particularly military, research. The panels reviewed the state of research in six different fields: the design and use of man-machine systems; the capabilities and limitations of human performance; decision processes in the individual; team functions; the adaptation of complex organizations to changing demands; and persuasion and motivation.42

In the group’s communique to the academic community, Bray said that they had undertaken to determine the

research on human behavior required to meet long-range needs of the Department of Defense . . . What kinds of problems will the Defense Department face in the future for which research in psychology and the social sciences may help to provide the answers? How would the products of successful research be put to use? . . . Defense managers do not now have the basis for sophistication and inventiveness about people that they have . . . about the production or the development of weapon hardware. Thus the key concepts behind the reasoning and conclusions expressed here is that Defense management needs a technology of human behavior based on advance in psychology and social sciences . . . including new concepts and attitudes about people — based on advancing scientific methodology.43

The Bray group’s overall recommendation was for implementation of a systems approach through increased funding of “technologically oriented long-range studies within the general fields of human performance, military organization, and persuasion and motivation,”44 coupled with contracts for large numbers of small-scale studies. The basic research of concern included such mainstream psychological issues as interpersonal relations, social perception, and group psychology, along with a heavy emphasis on team performance, composition, organization and training. They also wanted to know “all that can be known about persuasion . . . the complexity of attitudes and their relation to behavior . . . Military support should seek to integrate basic and applied research in the pursuit of a technology of persuasion.”45 In order to achieve these goals, the study recommended providing

. . . relatively few capable scientists with superb facilities, adequate interdisciplinary and technical help, and continuity of support. The need is to instill in the key scientists involved a desire to improve national defense through systematic technological development of their subjects and to support them in a manner adequate to their task. 46

The DOD accepted the Bray group’s recommendations and ordered the Army’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) to put them into operation in 1961 — the year of the first large build-up of U.S. combat troops in Viet Nam and the initiation of the new strategy of limited land war in Southeast Asia. ARPA established a Behavioral Sciences Council to continue with research on persuasion, motivation, and social change in the neocolonial countries. Meanwhile, Ithiel de Sola Pool (M.I.T.), J.L. Kennedy (Princeton), K. Knorr (Princeton) and C.A.H. Thompson (Rand) organized a second Smithsonian panel which worked for three years under military contract on the question:

How can a branch of social science be produced which takes upon itself a responsible concern for national security matters, and how can talented individuals from within social science be drawn into this area: That this is feasible and deserves to be attempted is a thesis underlying the efforts of the committee which produced this volume. 47

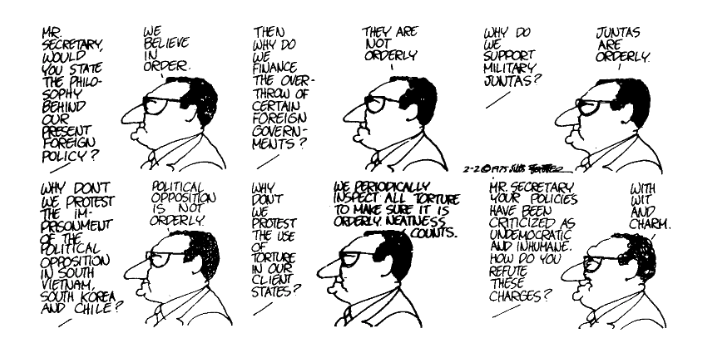

Its report laid the groundwork for a social science of counterinsurgency. It states that modern warfare is a matter of “gigantic organizations” engaged in “intercultural operations,” social science would be needed to find out “how to reach men of particular cultures, ideologies, and personalities” in countries “at the edge or over the edge of insurgency,” the counterinsurgency task was nation-building:

an adequate communication system, a growing economy, faith in progress, a set of political parties and pressure groups working toward national goals, a disciplined civil service, a sound currency, literacy, an education system, an honest government, and a modern ideology . . . Hence we conclude that in an age of automatic weapons military men must deal with more social relations problems, not fewer. And more, the human dimensions have become so complex that intuition alone is no longer capable of dealing with them. Science is called for.48

With this in mind a three-part strategy was worked out that would: (1) describe the military’s tasks and indicate the appropriate research, (2) focus military and social scientific attention on the tasks and (3) fund and institutionalize the research and recruit intellectual workers and consumers for its products.

This report also outlined ways in which social science research could be of use to the intelligence agencies: By studying aspects

(a) of the capabilities, practices, and objectives of states in international affairs and (b) of the domestic structures and functions (whether political, social or cultural) with which these international capabilities, practices, and objectives are reciprocally related . . . Much of the information produced by social scientists is of immediate use to intelligence, even to the extent that social scientists do not generate information about aspects of the environment that are of prime concern in intelligence. However, it is social science methods of gathering data, deducing data from other data, and of establishing the validity of data that are of particular value — in principle at least — in producing appropriate kinds of information for intelligence.49

Finally the Pool group spelled out how academic social scientists could work in counterinsurgency planning with the military. Their analysis said that

the study of internal war is bound to be largely symptomatology, concerned with the discovery of symptoms indicating, with a high degree of accuracy, that internal war will occur in the society’s future.50

The most important problems internal wars raise are precisely those we now study least: (a) how to anticipate internal wars (that is, . . . the preconditions of internal wars), (b) how to prevent them, and (c) what to do after hostilities cease. Of those problems, the first two are obviously the more important. If they are solved, the third need never arise.51

“Internal war” is military euphemism for revolution, civil war, rebellion, guerrilla warfare, coup d’etat, terrorism and insurrection. U.S. counterinsurgency social scientists define internal wars as the use of “violence to achieve purposes which can be achieved without violence,”52 thus missing completely the development of the contradiction between imperialism and liberation struggles in all of the areas of Southeast Asia formerly colonized by France. Counterinsurgency strategy dictates that early detection of the potential for armed struggle among the people of a country is critical for subverting that struggle, and is thus an attempt at a technological solution to a problem whose only solution can be political. A people organizes for armed struggle only when its goal cannot be achieved in any other way. At such a time, only destruction of the ancien regime and revolutionary transformation of the relations of production — a political solution — will alleviate the “preconditions of internal war.”

But the organizers of social science work believed they could create a technology of social surveillance which would give the U.S. ruling class pre-emptive strike capacity. What Pool et al did was to arrange an academic symposium thorugh the Special Operations Research Office (SORO)53 called “The U.S. Army’s Limited War Mission and Social Science Research.” This was the DOD’s organizing conference for Project CAMELOT. Some 300 social scientists gathered at the symposium were given the logic of their function as counterinsurgents:

In many developing nations where there is no direct negotiation or military confrontation with our major antagonists, the national interest requires our military participation when the military threat factor is but one of the several important factors to be faced in each situation. Military involvement is required long before events reach the stage when maximum physical force is appropriate or required.

There are military capabilities and skills which in prior wars were either ancillary or subsequent to use of direct physical combat capabilities — psychological operations, unconventional warfare, civic actions, military aid and advice. These capabilities have become the primary components of the military counterinsurgency weapon system, retaining the direct physical combat capabilities in a ready, indispensable, and highly critical reserve status.

Success in the counterinsurgency mission is as much dependent on political, social, economic, and psychological factors as upon purely military factors, and sometimes more so.54

Whether one is concerned with programs to alleviate political, social, or economic sources of discontent, with techniques of indirect influence, with the social environment in which actions occur, or with the social and political factors which are targets of action, the kind of underlying knowledge required is the understanding and prediction of human behavior at the individual, political and social group, and society levels. The systematic acquisition of such knowledge is the business of the behavioral and social sciences . . .

In addition to the acquisition of relevant knowledge in the classical scientific sense, scientists must explicitly define the linkage, whether immediate or remote, of the knowledge acquired or being acquired to specific operational problems and continually assess the import of such knowledge to solution of the problem.55

Producing the research their employers wanted would involve social science counterinsurgent’s carrying on what they normally did, but within an explicitly stated strategy for application. The social science literature-at-large would be used the way Kennecott uses Chilean copper. Academic social scientists would research and think and publish, and the ruling class would use the results in executing its policies.

Chief of Army Research and Development Lt. Gen. A.G. Trudeau told the symposium audience:

I am concerned about the sociopsychological factors basic to concepts and techniques to be developed for successful organization and control of guerrillas and indigenous peoples by external friendly forces . . . [emphasis added] 56

If insurgent strength flowed from the people, then “external forces” clearly had to try to control the people. The Western variety of 20th-century social science was thought to be an appropriate weapon to achieve this objective.

[We need] systems of control to manage conflicts at a rational level . . . The problem, after all, is to achieve objectives on the social groupings, by means of social groupings. There is a certain amount of hardware involved, too, of course, but men and their motives are at the heart of the matter. 57

Winning hearts and minds.

We are in the business of using people. All of us are these days. Some people don’t want to be used. Maybe you can help us solve that one. 58

But the organizers of the symposium were not merely interested in proposing areas of research. They also wanted now to direct the conduct of that research:

Attack fearlessly and without emotional or ideological distortions the question whether the means on which we rely to cope with the sources of turbulence in the new nations are adequate, whether we can steal our enemies’ thunder. 59

Social science offers, through the disinterested collection of data and analysis of behavior, the most reliable information we have about human institutions. 60

And finally, from the Army’s Chief of the Office of Research and Development:

We feel that a military social science research program will receive long-term support only if it emphasizes the conduct of research and refrains from journalistic comment on world affairs.61

In other words, the social scientists at this symposium were to have the freedom to do the required work if they wanted to, but they were not supposed to tum their inspection apparatus to the question of how they as human beings were acting in human society. For that would not be value-free social science. The claim that positivist methodology unearthed unbiased social knowledge is itself an item of dispute, but the injunction to separate the social function of their work from its content is an attempt to perform bloodless psychosurgery on the academic mind.

The SORO symposium created the population for take-off into a centrally organized, massive social science enterprise to gather data for counterinsurgency. Once that was accomplished the creation of CAMEWT was itself simple and could be handled through bureaucratic channels: the Defense Science Board took the PoolSmithsonian report and in the spring of 1964 created a subcommittee to decide how to implement its recommendations.

In March 1965 the Army was instructed to establish a “centrally coordinated applied-research effort” in the Washington D.C. area on behalf of the DOD. At the same time, ARPA was given the responsibility for organizing “supporting research in the universities,” in accord with guidelines spelled out by the Defense Science Board report. In addition, the Air Force, Navy and ARPA would be involved in “smaller related research efforts,” complementary to that outlined above.62 The centrally coordinated applied-research effort in the behaviorial and social sciences was Project CAMELOT,

a study whose objective is to determine the feasibility of developing a general social systems model which would make it possible to predict and influence politically significant aspects of social change in the developing nations of the world. 63

Selected academics were invited, in August 1964, to a month-long meeting to be held in August 1965 in order to review the research design. August, 1964, it must be remembered, was when the Tonkin Gulf incident was staged. Instead of accepting its evident military defeat in Viet Nam, the U.S. secured the official sanction of Congress to throw almost its whole army against the people of Viet Nam. Counterinsurgency was about to get its first full-scale field test. The Army’s SORO was to administer the espionage work of gathering the social science data which would be the content of CAMELOT and the CAMELOT conception was to be the secret of control without B-52 bombing. But neither social scientists nor B-52 bombers could halt the struggle for liberation that the Vietnamese people had been waging for decades.

In 1965 CAMELOT was accidently exposed and several layers of administration between the DOD and its social science operatives had to be elaborated to clean up its appearance, but its work proceeded as planned. Perhaps the main consequence of CAMELOT’s exposure and supposed termination was a proliferation of studies on how to organize the military social science work deemed necessary without risk of such embarrassment.64 The social-systems simulation modeling for which CAMELOT was to have been the feasibility study had by the time of this writing become fully operative in the arsenal of the U.S. ruling class and was used in the 1973 coup in Chile which restored U.S. hegemony over that country’s economy.65

In 1965 CAMELOT was accidently exposed and several layers of administration between the DOD and its social science operatives had to be elaborated to clean up its appearance, but its work proceeded as planned. Perhaps the main consequence of CAMELOT’s exposure and supposed termination was a proliferation of studies on how to organize the military social science work deemed necessary without risk of such embarrassment.64 The social-systems simulation modeling for which CAMELOT was to have been the feasibility study had by the time of this writing become fully operative in the arsenal of the U.S. ruling class and was used in the 1973 coup in Chile which restored U.S. hegemony over that country’s economy.65

Since 1965 the resources formerly allocated for CAMELOT have been used “to redesign research tasks” concerned with measuring insurgency potential and determining how “military assistance and allied programs can have increased effectiveness.”

The initial objective will be to develop a research plan that will specify those research tasks necessary to ultimately identify the parameters significant in detecting social unrest which leads to Communist penetration of the society and potential Communist-inspired revolt in developing nations . . . 66

Conclusion

What this essay has sought to establish is that from the beginning the social sciences in the U.S. were guided by the needs of the owners of North American industry to manage the social relations of capitalist production and to control markets and resources on a global scale. It examines only one of the processes of integration between the social sciences and capitalist priorities — that which results from the central government’s requirements for a technology of population management. Originally, federal organization of the social sciences meant the invention of social devices to monitor the immigrant labor force, acculturate it, and exterminate the tendency to socialist organization imported in its baggage. Later, as the U.S. engaged in struggles against its capitalist rivals and moved to displace European powers by reestablishing imperial domain on a supposedly more workable basis, the social science establishment turned its efforts to figuring out how to subvert popular movements that opposed foreign control and exploitation.

The social sciences are servomechanisms to the administrative institutions of the military, political, and economic sectors of Western capitalism, but at no point have these interests made their hegemony over the general thrust of social science research overt. Intellectual workers have been able to believe that they are attracted to particular lines of scientific inquiry purely on the basis of their intrinsic merits. The means of control are subtle. Our question, then, is how to rattle the tight complacency of the academic’s world: how to subvert the smooth operation of its ideological and practical control. Obviously, one line of struggle is to blast away the murky fog which conceals the mechanisms of control. This essay is intended to contribute to that enterprise.

An equally necessary contribution, though, is to thoroughly abandon the bourgeois mode of doing social science research work. At its core, that means shifting the ownership of the products of our intellectual work from the ruling class to some sector(s) of the working class. If our social science research work were to be dictated by the practical needs of political work we were engaged in with others. then its products would automatically be appropriated by some element of the class whose historical role we share. “The Literature” would have to be abandoned-as a repository of our research products; it’s a ruling class depot every bit as alienated from working class access as a Cargill grain elevator.

No science work has ever been value-free; every piece of science work is done in behalf of a social class. It’s clear that we have to get a lot more clearer about how to do science for our class.

Carol Cina

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 2 <<

FOOTNOTES

- In 1958, the National Science Foundation (NSF) reported that possibly as much as two-thirds of the expenditures for research and development performed by colleges and universities comes today from the Federal Government.” (NSF, Government-University Relationships in Federally Sponsored Scientific Research and Development, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, April 1958, p.1). In 1973; about 70% of research and development in universities and colleges was being paid for through the Federal Government. (NSF, Expenditures for Scientific and Engineering Activities at Universities and Colleges, Fiscal Year 1973, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, July 1975).

- I am indebted to David Eakins (The development of corporate liberal policy research in the United States, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms, No. 66-9/902, 1966) for his extensive archival research on the facts of the formation of the early policy research organizations, and especially for the fact that the new political economists transmitted the ideas of Bismarck’s welfare state to the United States.

- The book first to elaborate the concept of corporate liberalism was James Weinstein’s The corporate ideal in the liberal state 1900-1918, Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

- E.g., Richard T. Ely, Edmund J. James, E.A. Seligman, Henry C. Adams, Henry Farnam, Simon Patten, and John Bates Clark.

- Franks, P.A. A Social History of Social Psychology. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1975; Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms.

- Eakins, D. op. cit., p.115.

- Council for National Defense, National Research Council. Basis of Organization and Means of Co-operation with State Councils of Defense. Wash. D.C.: May 1, 1917, pp. 1-2.

- Report of the National Research Council, 1916. In Report of the National Academy of Sciences. Wash. D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916, p. 32.

- Council of National Defense, National Research Council. op. cit., p. 11.

- National Research Council. Consolidated report upon the activities of the NRC 1919 to 1932. The Carnegie and Rockefeller groups continued to supply substantial support, including a Carnegie purchase of a building on Constitution Avenue in Washington to house the Council’s offices.

- Third annual report of the National Research Council. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1919.

- Ibid., p. 25.

- Ibid.

- National Research Council, Consolidated Report, op. cit., p. 67.

- Third Annual Report of the National Research Council. In Report of the National Academy of Sciences. Wash. D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918, p. 42.

- The surveying agency was called the Research Information Service.

- Eakins, D. Op. cit., chapter 5.

- Recent social trends in the United States. Report of the President’s Research Committee on Social Trends. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1933, 2 vols., pp. 5 and lxxi.

- Ibid., p.lxii.

- Research-a national resource. Report of the Science Committee to the National Resources Commmittee. (3 vols). Part 1: Relation of the federal government to research.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- National Science Foundation. Organization of the federal government for scientific activities. Wash. D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1956, p.3.

- Bush, V. Science: The endless frontier. Wash. D.C., 1945 (NSF reprint, July 1960), xiii.

- Which is not to suggest that the Viet Nam War is the last of the series. See “The Great South Asian War — Mercenary Strategy for the Endless War,” in Michael T. Klare, War Without End: American Planning for the Next Vietnams, New York, Vintage Books, 1972, for a discussion of the Pacific Basin economic holdings which necessitate continuing military action in that region.

- See, e.g., Harold Isaacs, “Independence for Vietnam?” In Marvin E. Gettleman, Ed. Vietnam: History, Documents and Opinions on a Major World Crisis, New York, Fawcett, 1965, pp. 37-55.

- See I.F. Stone, The Hidden History of the Korean War, New York, Monthly Review Press, 1952.

- Office of Naval Research. Annual Report, fiscal year 1950. Wash. D.C.: Department of the Navy, 1950, p.1.

- Ibid.

- National Science Foundation (NSB 69-3), 1969. The behavioral Sciences and the Federal Government. Report of the

- National Science Foundation. Federal funds for research, development, and other scientific activities (title varies). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, annually 1956-71.

- Office of Naval Research. Annual Report, op. cit., pp. 15-16.

- The advisory panel consisted of Margaret Mead, Columbia University; John G. Darley, University of Minnesota; Pendleton Harris, Social Science Research Council; E. Lowell Kelly, University of Michigan; Rensis Likert, University of Michigan; George Lombard, Harvard University; F.F. Stephan, Princeton University; George Saslow, Washington University in St. Louis; Jerome Pataky, Navy; and J.S. Bruner, Harvard University. Past Panel members had been E. Wight Bakke, Yale University; Ruth Benedict, Columbia University; Erich Fromm, Bennington College; John Jenkins, University of Maryland; Alexander Leighton, Cornell University; Kurt Lewin, Director, Research Center for Group Dynamics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Dael Wolfle, American Psychological Association official; and Dexter Keez [–] McGraw-Hill book company.

- Guetzkow, H. (Ed.) Groups, leadership and men. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963 (originally published in Pittsburgh by the Carnegie Press, 1951), p.3.

- Ibid., p.4.

- Office of Naval Research. Annual Report, 1950. Op. cit., p.4.

- Ibid.

- Guetzkow, H. (Ed.) Groups, leadership and men. Op. cit., p.4.

- Op. cit.

- National Science Foundation. Organization of the federal government for scientific activities. Op. cit., p.9.

- Lyons, G. The uneasy partnership: Social science and the federal government in the twentieth century. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1969, p.137.

- Klare, M., Op. cit., chapter 1.

- The uneasy partnership, Op. cit., pp. 148-149.

- Broy, C.W. Toward a technology of human behavior for defense use. The American Psychologist, 17, August 1962, pp. 527-529.

- Ibid., p.527.

- Ibid., pp.538-540.

- Ibid., p.541.

- Pool, I. de S. et al. Social science research and national security. Wash. D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, March 5, 1963, p. 10.

- Ibid., pp. 7-10.

- Ibid., 79-80.

- Ibid., p. 84.

- Ibid, p. 109.

- Ibid., p. 102.

- The Army’s social science counterinsurgency research center, established at the American University in Wash. D.C. in 1956. Its name was changed to Center for Research in Social Systems (CRESS) in 1966. Resistance from within academia caused it to be phased out as a federally funded research and development center at the end of fiscal year 1970; its cover was switched from American University to the American Institute for Research (AIR).

- Special Operations Research Office. Symposium proceedings: The U.S. Army’s limited-war mission and social science research, March 26, 27, 28, 1962. Wash. D.C.: The American University, June 1962, pp.v-vii.

- Ibid., pp.x-xii.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Ibid.. p. 48.

- Ibid., pp. 88-89.

- Ibid., p.171.

- Ibid., p.181.

- Ibid., p.359.

- U.S. House of Representatives. Behavioral sciences and the national security. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Hearings, Part 9, 89th Congress, 2nd Session, 1966, pp. 72-74.

- Horowitz, I.L. (ed.) The rise and fall of Project Camelot. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1967, p.47.

- The behavioral and social sciences: Outlook and needs. Report by the Behavioral and Social Sciences Survey Committee. Wash. D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1969. Knowledge into action: Improving the nation’s use of the social sciences. Report of the Special Commission on the Social Sciences. Wash. D.C.: National Science Board — National Science Foundation (NSB 69-3), 1969. The behavioral sciences and the federal government. Report of the Advisory Committee on Government Programs in the Behavioral Sciences. Wash., D.C.: National Academy of Sciences (NAS Publication 1680), 1968. Behavioral and social science research in the Department of Defense: A framework for management. Report of the Advisory Committee on the Management of Behavioral Science Research in the Department of Defense, Division of Behavioral Sciences, National Research Council, Wash. D.C.: National Academy of Sciences, 1971.

- North American Congress on Latin America. Latin America and empire report, Vill (6), July-August 1974. See also Fred Landis, The CIA Makes Headlines, Liberation, March/ April1975. Also, Social Psychology, Simulation Modelling, and U.S. Neocolonialism, Psych-Agitator, Fall 1975 (available upon request from Psych-Agitator, Psychology Department, State University of New York, Stony Brook, N.Y. 11794).

- U.S. House of Representatives. Behavioral Science and the National Security, op. cit., pp.32-33.