This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Diagnosis: Work-Related Disease

by Fran Ansley & Brenda Bell

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 7, No. 5, September 1975, p. 19–21 & 34–35

This is an adaptation of an article which originally appeared in Mountain Life and Work—a publication of the Council of the Southern Mountains. It was expanded and modified for use here by a member of our editorial collective with the permission and cooperation of the authors.

As Americans living in an industrialized society, most of us hold jobs that unnecessarily endanger our health. We will not overcome health hazards unless we organize and demand greater worker control over the production process. But not all workers share exactly the same concerns. Organizing will of necessity take place around those health concerns each group of workers feels most threatened by, and is most willing to risk and sacrifice for.

Women in the Work Force

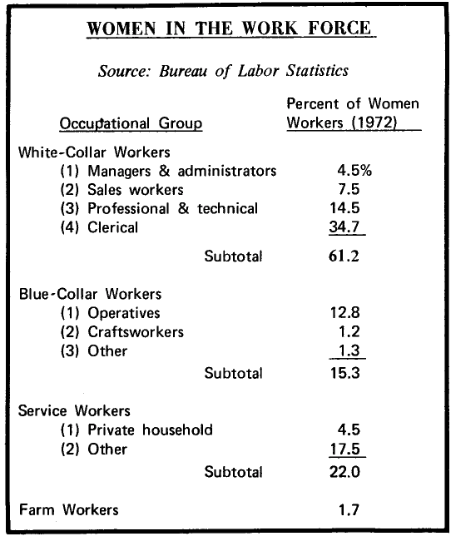

Women form a distinct group within the work force. Sexist tradition has placed us in a set of sex-related social roles and it has thus led us to hold certain types of jobs [see box] with particular sets of problems.

Most women are housewives and mothers, who are denied even the right to be called workers. These millions of women lack the most basic of workers’ rights—to a fair wage, to protective legislation, to unionize.

What about the 31 million paid women workers? Almost 7 million of us work in service industries—as janitors, in food preparation and serving, and as health and educational aides—in hospitals, private households, restaurants, and in schools. These low-skilled jobs all too often offer low pay and high abuse. These women, like housewives, lack many of the most basic workers’ rights.

Another 18-19 million women have paid, non-professional jobs, most often in manufacturing or in clerical work (about 15% and 35% of paid women workers, respectively). Even these, the “better-off’ women workers, are less likely than men to belong to a labor union. And they are far less likely to be union officers.

And finally, many women across the economic spectrum who have the dual responsibility of earning a living and maintaining a home find it necessary to have part-time paid work. These part-time workers are too often denied fringe benefits, such as health insurance. As a group, they are also more likely to be ill treated—with lower pay, less union representation, fewer rights, and fewer protections.

Job Hazards for Women

Most women hold relatively powerless positions in this society. This adversely affects our ability to solve occupational and other problems. In an unbroken cycle of cause and effect, women are forced to take the worst jobs because we are powerless, and we are powerless in part because we hold the worst jobs with the longest hours, the lowest (or no) pay, and the least control.

Most discussions of job hazards that concern women focus on pregnancy and reproduction. Attention is directed to problems such as the following:

- radiation and chemicals which can increase the incidence of birth defects.

- exposure to chemicals which can damage the fetus or are a particular hazard to pregnant women. (For example the anesthetic, halothane, is suspected to be the cause of the much higher rate of spontaneous miscarriage suffered by operating-room nurses as compared to other women.)

- physical hazards and types of work that should not be performed by pregnant women.

- policies concerning maternity and post-maternity leaves.

Such discussions, while relevant, are narrow and often sexist in scope. (Genetic damage leading to birth defects is also a problem for men and discussions of leaves for child care should not perpetuate the repressive social bias that exempts men from this responsibility.) Another danger is that considerations such as these have often been used to discriminate against women and deny them a whole range of job opportunities. Research must be done on these problems and women must organize and demand the involvement that will win adequate protection for all workers and their families. But, it is vital to recognize that the most important and pervasive occupational health concerns affect us throughout our working lives, not because we are biologically different from men, but because of our sexually defined social roles. The generally ignored social factors that women must face exacerbate our health problems, and often prevent us from solving the problems we as women, are most likely to suffer.

Southern Garment and Textile Industries

To get a better idea of how this works, it might be helpful to focus on some concrete examples. In the Appalachian south, two industries which employ large numbers of women are garment and textile factories. As these are industries with which the authors are most familiar, some detail will be given about the health-and-safety hazards facing women in these jobs. They provide many examples of the occupational-health problems faced by working-class women (and men) in other industries nationwide.

To get a better idea of how this works, it might be helpful to focus on some concrete examples. In the Appalachian south, two industries which employ large numbers of women are garment and textile factories. As these are industries with which the authors are most familiar, some detail will be given about the health-and-safety hazards facing women in these jobs. They provide many examples of the occupational-health problems faced by working-class women (and men) in other industries nationwide.

Women who work in garment factories and textile mills generally hold the lower-paying, least-skilled positions. In the garment industry, women operate the sewing machines and inspect finished products, while men hold the scarcer, higher-paying cutting and mechanic jobs. There are many kinds of industrial sewing machines, such as binders, double-needle seamers, hemmers, and the dangerous snap machines, to name a few. The rate of pay usually depends on the type of machine being operated, and the type of clothing being made. In textile mills, where workers spin thread and weave or knit cloth from raw fibre, women perform a broader range of jobs but are still not often found in the male-dominated positions of loom-fixer and dyer. Winding, spinning, weaving and inspecting are departments generally filled with women in the mills.

There are garment factories scattered throughout southern-Appalachian towns and more are being built in rural counties. Large companies such as J.C. Penney, Sears, and Montgomery Ward contract work with these places, where wages are usually the minimum, and where there is most likely no union (only 10 to 15% of all southern textile workers are organized). Likewise, textile mills dominate the employment scene in the North and South Carolina and Georgia towns where they are most heavily concentrated. These factories and mills are often the only source of employment for women, and the employers know this.

There’s no where else for us to go to work—and we need work. If there was some competition around, maybe the bosses wouldn’t treat us so hateful. They’d know we’d quit and go somewhere else. But I have to keep my job—you got to take what the boss puts on you.

Stress

One of the most pervasive and common ailments that garment-factory and cotton-mill workers share with millions of other women in the workforce is stress. Stress produces both physical and emotional changes in a person, wearing her down and opening the door to many serious illnesses. Chronic stress may lead to ulcers, migraine headaches, asthma and heart disease.

Stress is caused by many factors—speed-ups, long hours, shift work, underpay, poor working conditions, assignment to rapid and repetitious tasks ( particularly under the piece-work system) and pressure from supervisors.

The biggest, most important thing about health of factory women, I’d say, is working women too hard—pushing, pushing, pushing, all the time. They give us new material and a new style, and don’t give any adjustment in our rates. They want you to get to a certain speed of production, then they want you to go faster, faster. If you don’t make production on a new style, then you’re out. You get paid so little anyway. You have to push all the time to make it worth your while to go in there.

The biggest part of the women takes nerve pills. I’m on them myself. You just get so nervous, pushing all day. One woman works with me went to a doctor in the next town for her nerves. She was just all worn down. She said he said to her, ‘Tell me, what are they doing to the women down there? I’m going to take a day off and go see for myself.’ He said it seems to him from all the women that work there that come to him, 95% is on nerve pills, and the other 5% need them! It’s bad, really bad.

Tranquilizers and other barbituates keep many women going, or keep them cooled out enough to deal with strains and tensions of their lives, inside the factory and out.

Most women go home to a second job. If a woman is married, she usually tries to be supportive to her husband. If a couple works different shifts, and their children are in school, chances are the wife will be feeding and taking care of people on three different schedules. If she has no husband, and is the sole support of her family on a woman’s pay, then that is a huge responsibility:

I worked seven nights a week for years, from 3 to 11. I had four small children that I made a living for. Had to do it. My husband—he took up with another woman and I wouldn’t live with him. He left me with four small children and I didn’t have no other way of making a living.

Noise

Noise, one of the most common occupational hazards, is also a problem for garment-and textile-factory workers. The textile industry is acknowledged to have some of the noisiest of all work sites—particularly the weave rooms, where high-speed shuttles make lip reading a way of life. The garment industry too, can be noisy. Put fifty industrial sewing and finishing machines into one room, and the there is a lot of noise. (1)

If you are new, and you aren’t used to the noise, you can’t understand the next person when she talks. But once you have worked a while you learn to know what others are saying even if you can’t hear them.

Respiratory Problems

Respiratory problems are another major complaint of workers in both industries. Women working in garment factories complain about bronchitis, which results from lint and dust (produced by rapid sewing, cutting, and handling of so much material in one large, open space) causing inflamation of the large airways in the lungs.

I got bronchitis six weeks after going to work there. I don’t know if the dust and fine lint caused it, but it sure did irritate it. A lot of women had bad coughs. I’d be in the rest room, coughing, and women would say, ‘Honey, I’ve had a bad cough for years,’ or something else like that. One told me she coughs up blood.

Many cotton mill workers suffer from a severe incurable respiratory disease called byssinosis (brown lung). This disease is believed to be caused by a reaction to a biologically active substance (researchers haven’t isolated the exact cause) in the brittle leaves around the cotton ball. When cotton is received at a mill, it still contains a lot of these leaves, and in the processing, a great deal of dust is produced, including tiny particles of this cotton trash. Workers who handle the cotton in the early stages of processing have been found to have the highest incidence of byssinosis. An estimated 17,000 active carders and spinners suffer from the disease. Many others have retired early because of disability. Symptoms are shortness of breath; a tightness in the chest (which is worse on Monday morning, or on the first exposure to the dust after a time off) and a cough, which frequently produces phlegm.

Many cotton mill workers suffer from a severe incurable respiratory disease called byssinosis (brown lung). This disease is believed to be caused by a reaction to a biologically active substance (researchers haven’t isolated the exact cause) in the brittle leaves around the cotton ball. When cotton is received at a mill, it still contains a lot of these leaves, and in the processing, a great deal of dust is produced, including tiny particles of this cotton trash. Workers who handle the cotton in the early stages of processing have been found to have the highest incidence of byssinosis. An estimated 17,000 active carders and spinners suffer from the disease. Many others have retired early because of disability. Symptoms are shortness of breath; a tightness in the chest (which is worse on Monday morning, or on the first exposure to the dust after a time off) and a cough, which frequently produces phlegm.

Byssinosis (which has been a recognized, compensable disease in England for more than 30 years) is not a compensable disease in most states. In those where it is, most cases have been settled quietly, out of court, because the companies want to avoid publicity which would encourage more claims. Doctors willing to diagnose byssinosis—or even admit that it exists—are more the exception than the rule!

Heat

Another source of health problems affecting cotton mill workers is heat. Certain sections of cotton mills, such as the carding and spinning rooms, are kept hot (about 90 degrees) and humid, in order to achieve the proper conditions for producing good-quality thread and material. Many of the mill workers we’ve talked with have brought up the heat as a major irritation; this woman worked for 26 years in the card room:

They had humidifiers, flying over our heads, to dampen the cotton so it would run good. And they had an old fan going around, blowing at us from the top down to the bottom. I perspired a whole lot—I come out wet, my uniform wringing wet, every time I come out of the mill.

Heat is not just an uncomfortable nuisance. Workers develop heat fatigue—an emotional response of irritability and tiredness which affects women on the job and at home.

Chemicals

Industrial chemicals—over 15,000 of them—are a major health hazard throughout industry. Thousands of new chemicals, most of them untested, are introduced into industry every year. Unfortunately, garment workers are among those women being exposed to both known and possibly dangerous chemicals.

Formaldehyde, which is used in permanent-press material, can irritate the eyes, throat and respiratory systems, sometimes to the extent that allergies develop, causing nasal congestion or asthma. Formaldehyde also can cause dermatitis, an itching and inflamation of the skin-a frequent ailment of women who handle treated material.

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers union, in agreement with the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, is conducting a study of worker exposure to formaldehyde, trichloroethylene and perchloroethylene. These are chemicals used in removing basting and in dry cleaning; they can cause liver damage. Recent research studies suggest that trichloroethylene, like vinyl chloride, may cause cancer.

Other Hazards

Many other hazards exist for women in the cotton mills and garment factories: most sewing machines don’t have needle guards to protect workers’ fingers and eyes, there is poor ventilation, poor lighting and practically non-existent sanitation.

In fact, like most workplaces, the health hazards are numerous—too numerous to all be dealt with here.

Organizing Around Health and Safety Issues

What is needed, of course, is for women to organize to change these conditions—those at the root of their oppression, and those which are the symptoms of it.

The two industries we have been discussing have been notorious for their resistance to organizing efforts by workers. People in many of these plants haven’t been able to win union recognition, a living wage, seniority rights, or the simplest grievance procedure, much less a safe and healthy work environment. There are some indications that workers may soon begin to reverse this history with the influx of Black workers in significant numbers into these industries, and with the rising militancy among some unorganized workers.

One of the indications that things are changing is the recent formation of the Carolina Brown Lung Association, an organization of active and retired mill workers, with chapters in North and South Carolina towns. This group, which is being aided in its efforts by the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA), hopes to force changes in state workmen’s compensation laws, and bring about stricter enforcement of cotton dust regulations, better benefits for workers, and a more stringent dust standard which would reduce the danger of brown lung. But, as expected, companies which long opposed organizing efforts by the TWUA are working hard against the campaigns of the brown lung movement.

The struggle for union recognition and safe healthy workplaces is a tough fight; one in which Southern mill and garment workers, women and men, need all the help and support they can get.

Fran Ansley and Brenda Bell

>> Back to Vol. 7, No. 5 <<

FOOTNOTES

- Noise, and the stress that occurs with it, affects workers’ health adversely, causing hearing, balance, circulatory, heart, and digestive problems. Federal OSHA hearings are currently being held on proposed noise level standards for industry which organized labor considers too lenient.