This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Asbestos: $cience for $ale

by David Kotelchuck

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 7, No. 5, September 1975, p. 8–16

For almost a decade exposes of worker deaths due to asbestos have commanded newspaper headlines. In 1972 the U.S. government held hearings on a new asbestos standard for the workplace. Yet today the human cost of asbestos exposure remains a public scandal.

Despite this recent publicity the dangers of asbestos were discovered not in the 1960’s, but back at the turn of this century: The first worker death due to asbestos exposure was diagnosed by a London physician in 1900.1 His report lay interred in government records for over two decades.

What the general public did not know, the asbestos industry and the workers certainly did. In 1918 U.S. and Canadian insurance companies stopped selling personal life insurance policies to asbestos workers.2 Also, many workers discovered the hazards of the job soon after being hired and quickly left.

Asbestos disease escaped notice by doctors, in part because its main effect was to exacerbate existing cases of tuberculosis or reactivate dormant cases. But perhaps a more basic reason was that the number of deaths was small, since the number of workers throughout the world was only a few thousand. The asbestos industry was still in its infancy in the early 1900’s, with world production of asbestos in 1920 at only 200,000 tons, five percent of present production.

The industry began its rapid growth during the post-World War I construction and automobile booms of the 1920’s. With this growth, inevitably, came an upsurge in worker deaths. The medical profession rediscovered asbestos disease in 1924, when Dr. W.E. Cooke reported in the British Medical Journal on the death of a 33-year-old woman from dust inhalation in an asbestos factory.3 By the end 8 of the 1920’s British doctors had reported a total of 12 cases. What’s more, in some instances asbestos disease was found at autopsy with no sign of tuberculosis, unequivocally implicating asbestos itself as the cause.

The “new” disease, called asbestosis, is caused by scar tissue forming around asbestos fibers trapped in the lungs, and is similar to coalminers’ black lung. Its earliest symptoms appear mild—a slight persistent cough and shortness of breath upon exertion—usually developing about ten years after first exposure to the dust. If exposure continues, the disease can eventually lead to serious lung damage and death.

In the United States the first asbestos death was reported in 1930. By 1935 a total of 28 asbestos cases had been reported in Great Britain and the United States.4 Industry had ignored all reports of asbestos disease in the past, but with the number of cases mounting it could no longer do so.

Corporate Strategy

During the 1930’s, Johns-Manville, giant of the U.S. asbestos industry, began developing a strategy that was to serve it well for more than 30 years. The main priority of the strategy was the company’s economic survival and its profits. These could not be taken for granted in the midst of a major depression and in the face of cutthroat competition with other companies, especially by a company that was in corporate terms still rather small.

The strategy developed on several fronts:

- build the company as rapidly as possible and weave asbestos into the matrix of the economy so that it would become indispensable.

- fund medical research that would discredit reports of asbestos hazards.

- keep a check on workers’ health while telling them as little as possible.

- keep labor unions out of the plant.

Becoming Indispensable

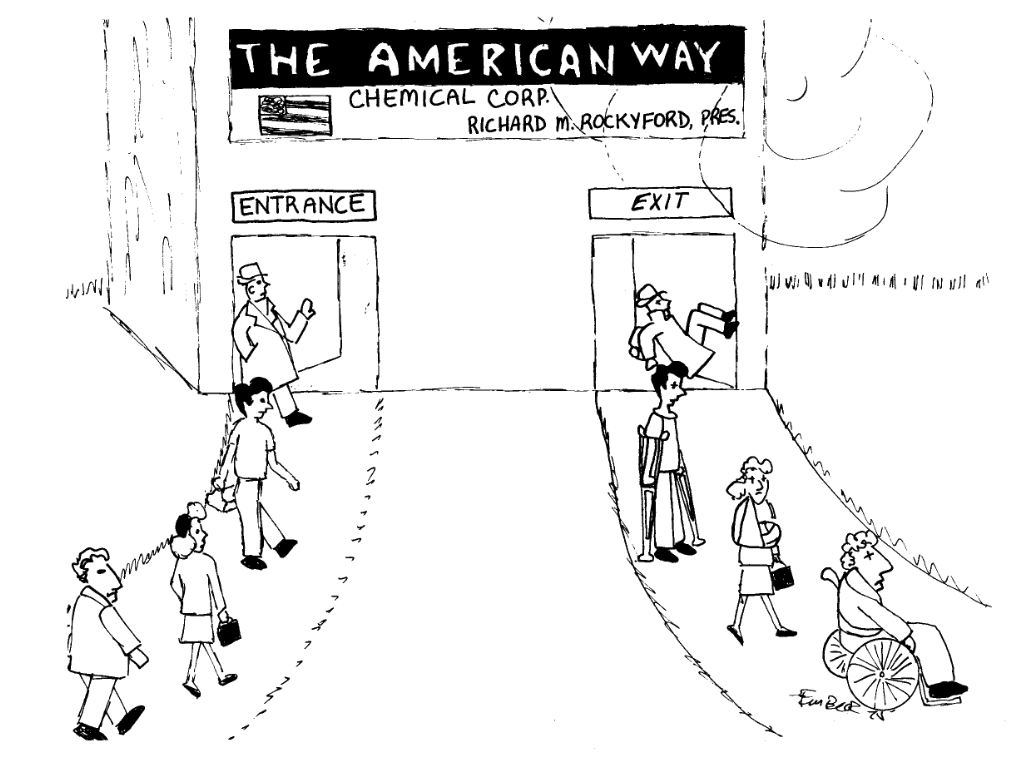

The first imperative—to grow as rapidly as possible—was of course common to all industry, and in this the asbestos industry succeeded phenomenally well. The engine of growth was the rapid development of literally thousands of new uses for the so-called “magic mineral”. For example, before World War I transite (asbestos-reinforced concrete) water pipe had not yet been developed; today it is the single major use of asbestos. Asbestos insulation for ships came into widespread use during the shipbuilding boom of World War II, endangering several million shipyard workers. Today the estimated 3000 industrial uses for asbestos include products as varied as insulation for Apollo space rockets, roof shingles, siding, brake lining, clutch facing, linoleum, electric wire casing, draperies, rugs, floor tiles, ironing board covers, potholders and fireproof clothing.

With this boom, almost all of it taking place after extensive reports of asbestos hazards, Johns-Manville sales grew from $40 million in 1925 to $685 million in 1971, making it among the hundred largest U.S. corporations. Today the U.S. asbestos-manufacturing industry alone employs 50,000 people, asbestos-insulation workers in the building trades number 40,000 and an estimated 5 million people work daily with asbestos-containing products. As a result of this enormous expansion it is almost impossible, in terms of present political realities, to phase out nonessential asbestos production.

Buying Science

The second prong of industry strategy was to buy scientific results that would refute the many case studies of asbestos deaths. In 1929 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company was commissioned by the asbestos industry to conduct a study on asbestosis. Under the direction of Dr. A.J. Lanza*, Assistant Medical Director of Met Life, medical examinations were conducted on a total of 126 asbestos workers, selected at random from five plants and mines in the U.S. and Canada, mostly Johns-Manville facilities. Sixty-seven of the 126 workers examined were classified as positive cases of asbestosis, 39 as doubtful and only 20 as completely free of any sign of asbestosis. On their face these figures represent an epidemic of disease. Calculated as percentages, the findings showed 53 percent of the workers having asbestosis, 84 percent with some signs of disease (positive plus doubtful) and only 16 percent with no signs of asbestosis at all. However, the authors did not publish these percentages. They simply listed the number of workers in each category and hurried on without comment. Short of suppressing the data, they could have done no less.

In addition to minimizing the incidence of disease, the authors also played down its severity. They dismissed workers’ complaints of coughing and shortness of breath, typical early symptoms of asbestosis, with the response, “Too much emphasis should not be placed on statements of subjective symptoms.”

The U.S. government served as handmaiden to industry in this case by publishing the Met Life study as a Public Health Report of the U.S. Public Health Service. This gave the study the imprimatur of the federal government despite its genesis in industry, its industry funding and its appalling pro-industry bias.5

Johns-Manville’s other venture into medicine was its funding of animal studies at the Saranac Research Laboratory in upstate New York beginning in 1929. Although this work was continued for the next 25 years, it was of such poor quality that the National institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NOISH) later deemed it of no use in setting an asbestos standard.6 Nevertheless, industry was able to cite the work as evidence of its “long concern” about asbestos hazards.

In 1935 another asbestos-related disease appeared. Two doctors from the Medical College of South Carolina reported a possible link between asbestos and lung cancer.7 By 1942 nine other case studies followed, showing that asbestosis victims suffer a high incidence of lung cancer.8 Two scientists from Saranac, Arthur Vorwald and John Carr, dismissed the conclusions because, they· argued, asbestosis victims might be especially susceptible to lung cancer.9 What was clearly called for was a large-scale , plant-wide study, a so-called epidemiological study, in which workers employed at some particular date were followed for a period of years and all cases of disease recorded. But the hitch was that the asbestos companies had custody of the personnel records on which such a study would necessarily be based, and they did not want the study to be conducted. In fact, it was not until 21 years later that the study was performed. In the interim the Vorwald-Karr paper was industry’s “proof” that no link existed between asbestos and lung cancer.

A question arises at this juncture: What became of the results of the scientific papers that first uncovered asbestos disease—28 in the case of asbestosis and 10 in the case of lung cancer? Apparently they just remained in the medical literature. Almost all the papers reflected a humane concern for the afflicted workers. But occasional appeals for help in dealing with the problem were invariably directed to industry instead of calling for public political discussion on controlling asbestos hazards-with the goal of eliminating all unnecessary uses of the material and controlling exposure when its use was mandatory. Unfortunately, the doctors and medical scientists were still wedded to a notion of professionalism that restrained them from communicating their findings with workers. Thus workers at the Johns-Manville plant in New Jersey reported that before the 1960’s they were not contacted by any of the doctors who had published papers on asbestos hazards.

* Eventually Dr. Lanza became Director of the Bureau of Occupational Safety and Health (BOSH), the toothless federal predecessor to the present Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Later he became chairman of the Department of Industrial Medicine at New York University Medical Center, and today the A.J. Lanza Institute for Environmental Medicine at NYU stands as his memorial. ↵

Keeping Workers Uninformed

Industry, which was responsible for workers’ health problems, withheld information about the hazards from their employees. For example, until recently the Johns-Manville medical staff denied workers access to their medical records. Furthermore, they refused to tell workers the results of physical examinations. Company spokesmen admit that until a few years ago the company did not tell workers that their respiratory problems were linked to asbestos. Joseph Kiewleski, an asbestosis victim, indicated that he was transferred without an explanation from a machinist’s to a janitor’s job after he had undergone a company physical examination. He found out from his own doctor years later that the reason for the job change was to remove him from the source of exposure.

Moreover, company doctors in their cursory examinations of workers missed the most blatant diseases. In 1971, Daniel Maciborski was diagnosed to have cancer at the age of 49, a few weeks after he had been given a clean bill of health by the company. He died seven months later.

The company also tried to attribute occupational diseases to other causes. According to Dr. Maxwell Borow, a local doctor, “They claimed that workers had pneumoconiosis from mining coal in Pennsylvania.” But ironically, after World War II the Manville N.J. plant had an influx of young veterans who had never mined coal and in fact had left Pennsylvania in part to avoid the black-lung disease that plagued their fathers.

Asbestos-Industry Unions

The only part of industry’s strategy that was not wholly successful in the period from 1930 to 1960 was its attempt to keep unions out of its plants. During this period most Johns-Manville plants were organized. But instead of having one or a few industrial unions at these plants, 26 different international unions were organized there, almost guaranteeing each a weak bargaining position with the company.

AFTER WORLD WAR II

Industry’s basic strategy, unchanged since the 1930’s, began to unravel in the 1950’s as a result of new medical reports of asbestos hazards. Individual case studies further linking asbestos and lung cancer kept accumulating.10 Finally in 1955 a member of England’s prestigious Medical Research Council analyzed government data on asbestos-industry deaths and found an unusually high rate of lung cancer among the workers.

In what for them was a lightning-fast response, the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association (QAMA) commissioned a study in the following year on lung cancer among Quebec asbestos miners.11 This was 21 years after the first reports linking asbestos and lung cancer. What industry badly wanted was a whitewash job-and it got one.

The study was conducted under a QAMA grant by the Industrial Hygiene Foundation (IHF, now called the Industrial Health Foundation). IHF, located in Pittsburgh, performs occupational-health studies for corporations. It is openly pro-management and is supported almost entirely by major U.S. industries.

As in the asbestosis case, the contrast is striking between the enormous size and scope of this experiment and that of the non-industry case studies-a fact that lent credibility to the industry study. The IHF investigation was an extensive epidemiological study of 6,000 asbestos miners from Quebec with five or more years of exposure.

All of this sounds impressive until one examines the IHF report itself.12 Among numerous errors in method was one central, scientifically inexcusable flaw-the investigators, Daniel Braun and T. David Truan, virtually ignored the 20-year time lag between exposure to an agent known to cause lung cancer and the first visible signs of disease (the so-called latent period). They studied a relatively young group of workers, two-thirds of whom were between 20 and and 44 years of age. Only 30 percent of the workers had been employed for 20 or more years, the estimated latent period for lung cancer. With so many young people in the study, too young to have the disease although they might well be destined to develop it, Braun and Truan of course did not find a statistically significant increase in lung cancer among the miners. As became obvious later, they had drowned out a clear danger in a sea of misleading data.

The practice of looking at a workforce with limited asbestos exposure is not an isolated error in a particular experiment; it is a hallmark of epidemiological studies funded by the asbestos industry. This was the reason that the scientists conducting the 1935 Metropolitan Life study did not find asbestosis in its advanced, most critical stage. Even in the 1970’s, researchers funded by industry continue to conduct studies on young workers despite scores of experiments by non-industry scientists showing that the various asbestos diseases take anywhere from 10 to 30 years to develop.

By 1960, medical research on asbestos was at a watershed. A total of 63 papers on the subject had been published in the U.S. and Canada and Great Britain. The 52 papers not sponsored by industry, mostly case histories and reviews of case histories by hospital and medical school staff, indicated asbestos as a cause of asbestosis and lung cancer. The 11 papers sponsored by the asbestos industry presented polar opposite conclusions. They denied that asbestos caused lung cancer and minimized the seriousness of asbestosis. The difference was dramatic—and obviously dependent on the doctor’s perspective, whether treating the victim of disease or serving as agent for its perpetrator.

The Lid Blows

In the early 1960’s the research picture changed dramatically as a result of three separate studies. In 1960 a new malady was added to the lexicon of asbestos diseases: mesothelioma, a rare and invariably fatal cancer of the lining of the chest or abdominal cavity.13

In 1963 a study of lung smears from 500 consecutive autopsies on urban dwellers in Cape Town, South Africa showed that the lungs of 26 percent had asbestos bodies, the characteristic bodies originally found in the lungs of workers with asbestosis.14 Both studies received extensive publicity and raised the specter of asbestos as a modern environmental hazard affecting all citizens.

To top this off, in the early 1960’s Dr. Irving Selikoff and his associates at Mt. Sinai Medical Center in New York broke industry’s hegemony over medical and personnel information by using the welfare and retirement records of the asbestos insulators’ union as the basis for conducting an epidemiological study. Now for the first time in the U.S., scientists not beholden to industry conducted large-scale definitive studies on groups of asbestos workers. Beginning in 1964 the investigators reported an unusually high incidence of lung cancer and mesothelioma among asbestos-insulation workers, with time lags of 20 and 30 years, respectively, between exposure and disease.15 By focusing on workers who were first exposed 20 or more years earlier, the studies highlighted its hazards. Together with the South African studies they made the “magic mineral” front-page news throughout the world.

Industry Fights Back

The asbestos industry responded to these reports by spending $8.5 million on research and development in 1972, a large fraction of which went to outside medical research centers.16 In contrast, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) spent a mere $260,000 on asbestos research grants that year.17

As a result, an industry that had only managed to generate 11 research papers on asbestos in the three decades before 1960 has come up with 33 in little more than a decade since then. The recent studies are just as self-interested as ever. Industry has stopped denying that asbestos causes lung cancer, mesothelioma and asbestosis (although it has not publicly admitted it, either). But research proposals that industry thought would minimize the problem or shift the blame have been given unstinting support.

Minimizing the Problem

A major epidemiological study was published in 1971 by J. Corbett McDonald and his associates at the Department of Epidemiology and Public Health at McGill University in Montreal. It was funded through a grant from the Institute of Occupational and Environmental Health of the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association.18 The subjects were 11,000 miners in the two largest asbestos mines in Quebec.

Like the earlier IHF study on asbestos miners, this one looks quite impressive until it is examined carefully. Then we find as before that the workforce studied has had relatively limited exposure, and that many other serious methodological errors were made.

Like the earlier IHF study on asbestos miners, this one looks quite impressive until it is examined carefully. Then we find as before that the workforce studied has had relatively limited exposure, and that many other serious methodological errors were made.

Let us consider the duration of exposure of the workforce. The research data shows that many of the miners included in the study worked in the mines for only a short time and then left. One-third of the miners in the study had worked less than a year in the mines, two-thirds had worked less than 10 years. So it is not surprising that their mortality was not much different from that of the general population. The authors go even further. They begin their comments on the results with the observation that workers in the asbestos-mining industry have “a lower mortality than the population of Quebec of the same age.”

What’s more important, the authors largely ignore the latent period between exposure and disease for lung cancer. They do not categorize workers by number of years since first exposure, which would highlight any latency effect. Workers with recent exposures, more recent than the 20-year latent period for lung cancer, are included in the study and may be placed in the same categories as those who have been exposed many years earlier.

In contrast, Selikoff and associates at Mt. Sinai in their earliest experiments only looked at workers with 20 or more years of work experience since first exposure.19 Thus they focused their attention on precisely that group of workers most likely to develop disease, and thereby found evidence of serious hazards.

In fact, studies not supported by industry have consistently found asbestos to be a serious health hazard. While Braun and Truan, and McDonald found no increase in mortality rate due to asbestos or only small increases up to 20 percent, studies not financed by industry reported an increase in mortality rate among asbestos workers of from 200 percent to 9,000 percent above that of the general population.

Another way for industry to gain time is to try to shift blame. So pro-industry scientists have recently concocted one theory after another purporting to prove that asbestos workers and their families were not dying from asbestos, but from some impurity, some contaminant or some unusual type of asbestos.

One of the early theories, by Dr. Paul Gross of the Industrial Hygiene Foundation, was that trace metals were contaminating asbestos and causing the diseases attributed to asbestos. This work was supported by industry for six years until Gross and supporters finally had to admit that the theory was incorrect.

Another theory is that certain types of asbestos tiber are dangerous, while others are safe. Ninety-five percent of the asbestos used in the U.S. and Canada is of one type, chrysotile. Since the bad-tiber theory has its origins in industry-sponsored research, it comes as no surprise that tiber types other than chrysotile have been blamed for asbestos disease.

Probably the ultimate in fishing around for something else to blame was the theory propounded by Gibbs of McGill University and funded by the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association, that the polyethylene bags in which asbestos is stored produce oils that contaminate the asbestos and might cause the cancer associated with asbestos.

Whether or not industry has lost these battles, the eventual outcome of each is less important than the fact that each salvo has tied up scientific resources, defined research issues and bought time. In the case of almost every industry proposal, some non-industry scientists have had to conduct experiments in rebuttal, using up some of the meager resources in the process.

Sitting on the Victims

While industry was mounting its medical and scientific counterattack, it had to deal with asbestos victims and their families. Many of the victims’ dependents filed suits against the company. To keep things quiet, Johns-Manville usually settled out of court. The average settlement in the mid-1960’s was $10,000. In recent years the company has increased the settlement for mesothelioma victims. It now pays the deceased’s hospital bills, as well as half the victim’s salary for the rest of the surviving spouse’s life. Asbestosis victims have fared even more poorly. In 1970 the awards for Johns-Manville’s asbestosis victims averaged $2,175.

Recently workers and their families have begun to institute large damage suits against individual companies. In California an asbestos worker won $351,000 in damages from a company physician who witheld information that he had developed asbestosis. This year in Paterson, New Jersey, the families of a number of workers who died of asbestos exposure sued the Raybestos-Manhattan company and its suppliers (Johns-Manville among others) for damages of $326 million. While such suits are filed after the fact of disease and death, the plaintiffs have often expressed the hope that the suits’ financial impact may be great enough to cause a major cleanup throughout the asbestos industry. However, U.S. courts have been notoriously unfriendly to labor in the past and would seem a weak reed to lean on now.

While victims and their families were trying to deal individually with the company, union locals such as the one in the Manville plant were slow to take any initiative on asbestos hazards. In 1970, for the first time in ten years, the union struck, crippling the plant for almost six months. The major concerns were bread and butter issues, September, 1975 but a vocal minority of younger workers began to raise questions about their health. When the strike was settled, the company agreed to permit workers access to their X-rays. As a “preventive measure”, J-M also consented to establish a joint union-management environmental-control committee. Union officials publicly proclaimed the committee a great victory.

But the company quite independently of this union management committee had begun a major cleanup of its plants in the late 1960’s, presumably in expectation of stiffer government regulations in the near future. Throughout all its plants Johns-Manville lowered dust levels by eliminating many intermediate steps in the production process, enclosing or bettering ventilation in some areas, and improving housekeeping procedures. In the textile division of the Manville plant, for example, steps have been eliminated from carting, spinning and warping, according to officials conducting a recent plant tour. Manville executives are elated. “By eliminating steps we don’t need, we also save money,” one engineer boasted. And, he might have added, the company cuts labor costs and improves productivity.

What happens to those whose jobs are eliminated? They are “absorbed in other parts of the plant,” according to Wilbur Ruff, Community Relations Director at the Manville plant. But that’s not the whole story. J-M has cut its Manville work force in recent years, mostly by attrition—that is, by not replacing many retirees and others who leave the plant. In the six-year period during which J-M was reducing dust levels, the nonsalaried work force at the Manville plant dropped almost 45 percent, from 3,200 to 1,800 employees, according to Ruff. The working people of Manville have exchanged jobs for improved health conditions at the plant.

The 1972 Asbestos Hearings

But however much the company was in control of events within its plants, constant publicity about scientific studies that demonstrated asbestos hazards took their toll.

Following passage of the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act in 1970 major attention was focused on a new national standard for asbestos exposure. At a hearing held in 1972, George Wright, Johns-Manville’s chief science advisor, was able to call on five studies supporting J-M’s contention that the standard of five asbestos fibers per cubic centimeter should be maintained, not lowered. Of the five studies, four had been funded by the asbestos industry.

These studies helped put a “scientific” cover over industry’s interests. Industry could not prevent the asbestos standard from being lowered to two fibers per cubic centimeter, but it contributed to a delay in its effective date for four years until 1976. Thus the corporations had won precious time to regain their initiative in the struggle. For workers too, the time lost was critical. Dr. Selikoff estimates that this delay eventually will take as many as 50,000 lives.

But even when the fiber limit comes down the battle is not over yet, not by a long shot. The 1972 NIOSH report on asbestos bases its two-fiber recommendation primarily on the British standard. This standard is now under question in England because the experiment it was based on appears to have underestimated the extent of disease. Also, whatever level is set, there is no known safe level of exposure for any cancer-causing agent, according to officials at the U.S. National Cancer Institute. Thus, public discussion about setting a legal exposure level in plants is largely based on a false premise-that a safe level of exposure exists.

Johns-Manville After 1972

Since the 1972 hearings, industry’s decades-old strategy has changed. For example, instead of forging ahead with development of new uses for asbestos, JohnsManville has for the first time seriously decided to diversify. It is planning to develop a major outdoor-recreation center in Colorado, and it is, with consummate audacity, selling environmental-control products and services to other companies based on the experience in its own plants. In fact, environmental controls have been extolled by the Wall Street Transcript as one of the company’s “hottest growth areas.” The corporation is also studying the use of fiberglass as a substitute for asbestos.

While Johns-Manville’s stocks have gone down in recent years, company sales went up and its profits are steady. In 1972, Value Line Survey called Johns-Manville “the picture of financial health.” To be sure, U.S. sales of asbestos are down, but Johns-Manville has been pushing its foreign sales and these have more than made up for domestic losses.

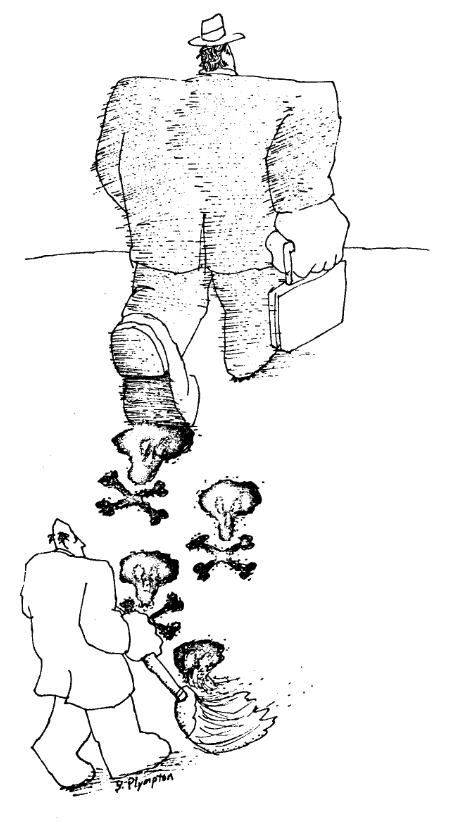

Not only have foreign sales increased, but the asbestos industry has also been exporting jobs, especially those in the dusty asbestos-textiles trades. Since 1968 asbestos textile imports from countries with weak or nonexistent occupational-health laws have increased from 0.1 percent to a whopping 50 percent of the total U.S. imports. Mexico’s asbestos-textile exports to the U.S. rose from a mere 180 pounds in 1969 to 1.2 million pounds in 1973. During the same period Taiwan’s exports rose from 0 to 1.1 million pounds and Brazil’s from 0 to 0.5 million pounds. Twenty-one of Mexico’s 23 asbestos-processing plants have been built since 1965. [ 18] Thus, industry has taken operations that would be difficult and expensive to clean up and has, with full knowledge of the consequences, exported them abroad to maim and kill foreign workers.

WHAT WENT WRONG

If, throughout this discussion, asbestos companies seemed largely in control of the situation, it is important to ask why workers and medical scientists friendly to them have not been able to turn the tide.

In the case of workers, the reasons are quite clear. Short of closing down asbestos plants, the best solution would be automation of the production process, thereby 14 removing workers from the exposure. While this appears technically feasible, in the present society it would be a disaster. Virtually all production workers, such as those at Manville, would lose their jobs and would be left to their own resources to find new ones. As one worker commented, “I’m 52. I been workin’ at J-M 27 years. Who would hire me? Where else could I go?”

A planned and people-oriented system could fmd alternative jobs for displaced workers. Then automation could be, in the fullest sense of the term, life-saving. But our society does not have this commitment. Instead, it discards people when they are no longer economically useful-as it has done to miners and aerospace workers, to mention only two examples. Thus workers continue to be forced into the no-win “choice” between their jobs and their lives. No wonder that they have been afraid to push for strong health and safety measures.

Worker-oriented scientists have played an important role in the asbestos struggle, but their failures were critical ones, which might have changed the situation decisively. For example, had scientists and doctors who first found evidence of asbestos disease brought it directly to workers in the plants, workers might have been much more willing to take on the company despite great odds, and the new information would have armed them in their effort. In fact in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, when the asbestos industry was still small, if medical people had not limited themselves to operating within narrow professional roles the expansion of the asbestos industry might have been nipped in the bud and thousands of lives might have been saved.

(A positive example of the importance of bringing medical information to workers is provided by the coalminers’ black-lung struggles. During the early 1960’s scientists and medical people travelled to union and community meetings throughout Appalachia reporting to workers results of their studies and discussing with them the dangers of black lung. Later analyses have shown that these scientists played an important role in the development of black-lung struggles.)

The interaction between workers and scientists need not be one-sided. Looking at the history of research on asbestos disease, it becomes clear that a decisive scientific turning point took place in the early 1960’s when the asbestos unions turned over their retirement and death-benefit records to Dr. Selikoff and thereby, for the first time, allowed non-industry scientists to examine the records of all workers in an industry. This provided critical new information on asbestos health hazards and helped overcome objections that earlier studies had focused on individual asbestos victims.

Today industry still seeks to dominate asbestos research. This is done by supporting individuals whose scientific practice demonstrates built-in biases useful to industry. These biases usually are the result of scientific and social values rather than dishonesty or conspiracy on the part of scientists. A critical examination of industry-funded asbestos research does not reveal overt falsification of data. In fact in many of the large-scale industry experiments (for example the Metropolitan Life study in 1935 and the McDonald studies in the 1970’s) data indicating asbestos dangers is circumspectly presented in the reports themselves.

It is clear that the critical difference between industry and worker-oriented research does not lie in the experimental methods employed, but in the questions that scientists try to answer and in the assumptions made when they analyze and present their data. If a scientist suspects that workers are often harmed on the job, he or she will adopt this as an implicit hypothesis and will focus attention on older, heavily exposed workers who are more likely to show signs of disease. Data will be presented that are designed to illuminate the hazard to this group of workers and summary and conclusions will typically begin with a statement about the most serious hazard uncovered by the study.

It is clear that the critical difference between industry and worker-oriented research does not lie in the experimental methods employed, but in the questions that scientists try to answer and in the assumptions made when they analyze and present their data. If a scientist suspects that workers are often harmed on the job, he or she will adopt this as an implicit hypothesis and will focus attention on older, heavily exposed workers who are more likely to show signs of disease. Data will be presented that are designed to illuminate the hazard to this group of workers and summary and conclusions will typically begin with a statement about the most serious hazard uncovered by the study.

On the other hand, a scientist who designs a study with the assumption that workers are not often harmed on the job is more likely to study a much larger, more heterogeneous group of workers in a given plant or industry. In this case, data will first be presented lumping the workers together into a single group, which tends to bury the effect of unhealthy subgroups within the larger group.

Summary and conclusions will usually open with a statement about the similarity in the mortality pattern of the entire group of workers as contrasted to that of the general population. A comparison of the papers of Selikoff and McDonald, for example, illuminates these differences clearly.

Pro-worker scientists have much to learn from studying and understanding these differences. Some of our main tasks are to learn how to frame research questions in a pro-worker format and then proceed to definitively answer them. Formal scientific and technical education can help us a great deal with the latter task. But we must learn for ourselves how to ask the right questions in occupational· health, since we are unlikely to acquire this skill at the university. At a later stage of the research process we must take the responsibility of sharing our findings with the workers whose health is affected.

Pro-worker scientists have much to learn from studying and understanding these differences. Some of our main tasks are to learn how to frame research questions in a pro-worker format and then proceed to definitively answer them. Formal scientific and technical education can help us a great deal with the latter task. But we must learn for ourselves how to ask the right questions in occupational· health, since we are unlikely to acquire this skill at the university. At a later stage of the research process we must take the responsibility of sharing our findings with the workers whose health is affected.

Throughout, we must acknowledge and be aware of economic and political realities. If we do not, we may, as in the case of asbestos research, win the battle to discover truth and lose the war to save human lives.

David Kotelchuck

(Based in part on” Your Job or Your Life” by Marsha Handelman Love and David Kotelchuck, Health/PAC BULLETIN, Mar., 1973 and “Asbestos Research” by David Kotelchuck with the assistance of Robb Phillips, Health/PAC BULLETIN: Nov./Dec., 1974. See these articles for more detailed discussion and references. Health/ PAC, 17 Murray St., NYC 10007)

>> Back to Vol. 7, No. 5 <<

REFERENCE

- H.M. Murray in Charing Cross Hospital Gazette (London 1900). Later published in Report of the Departmental Committee on Compensation for Industrial Disease (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1907), p. 127.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Occupational Exposure to Asbestos-Criteria for a Recommended Standard (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office,1972), p. 111-4.

- W.E. Cooke, “Fibrosis of the Lungs Due to the Inhalation of Asbestos Dust,” British Journal of Medicine II (1924) p. 147.

- D.S. Egbert, “Pulmonary Asbestosis,” American Review of Tuberculosis, XXXII (1935) p. 25.

- A.J. Lanza et al. “Effects of Inhalation of Asbestos Dust on the Lungs of Asbestos Workers,” US Public Health Reports Vol. 50, No. 1 (1935).

- NIOSH, op. cit., p. 111-12.

- K.M. Lynch and W.A. Smith, “Pulmonary Asbestosis,” American Journal of Cancer XXIV (1935), p. 56.

- H.B. Holleb and A. Angrist, “Bronchiogenic Carcinoma in Association with Pulmonary Asbestosis,” American Journal of Pathology, XVIII (1942) p. 123.

- A.J. Vorwald and J.W. Karr, “Pneumoconiosis and Pulmonary Carcinoma,” American Journal of Pathology (1938) p. 49.

- E.R.A. Merewether, Annual Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1947) and S. R. Gloyne, “Pneumoconiosis,” Lancet, 1 (1951), p. 810.

- D.C. Braun and T.D. Truan, “An Epidemiological Study of Lung Cancer in Asbestos Miners,” Archives of Industrial Health, XVII (1958) p. 634.

- D.C. Braun and T.D. Truan, “An Epidemiological Study of Lung Cancer in Asbestos Miners,” Archives of Industrial Health, XVII (1958) p. 634.

- J .C. Wagner et al., “Diffuse Pleural Mesothelioma and Asbestos Exposure,” British Journal of Industrial Medicine, XVII (1960), p. 260.

- J.G. Thomson et al., “Asbestos as a Modern Urban Hazard,” South African Medical Journal, 37 (1963), p. 77.

- Reviewed in I.J. Selikoff et al., Cancer of Insulation Workers in the United States, Lyons Conference on Asbestos (1972).

- Johns-Manville Corporation, Report to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, form 10-K (Washington: 1973) p. 6.

- NIOSH Contract and Research Agreements (Washington: U.S. Public Health Service, September, 1972), p. i-vi.

- J.C. McDonald et al., “Mortality in the Chrysotile Asbestos Mines and Mills of Quebec,” Archives of Environmental Health, XXII (1971), p. 677.

- Reported in Lifelines: Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union News, April, 1975.