This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Motivation or Manipulation: Management Practice and Ideology

by Jeanne Olivier, Patricia Browne, Sheila Cutler, Britta Fischer, Carol Hinchey, & Sarah Vinal

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 4, July 1973, p. 32 – 38

[The text below is an account of a symposium-confrontation on the topic of “job enrichment” which took place at Emmanuel College. The article which follows on the next page is an abridged version of a paper “Motivation or Manipulation” which was presented at this symposium.]

[The text below is an account of a symposium-confrontation on the topic of “job enrichment” which took place at Emmanuel College. The article which follows on the next page is an abridged version of a paper “Motivation or Manipulation” which was presented at this symposium.]

As far as Western Electric goes — It’s an alright place, but as far as the work we’re given, you could train a monkey, pay him six bananas, and you’d double the output.

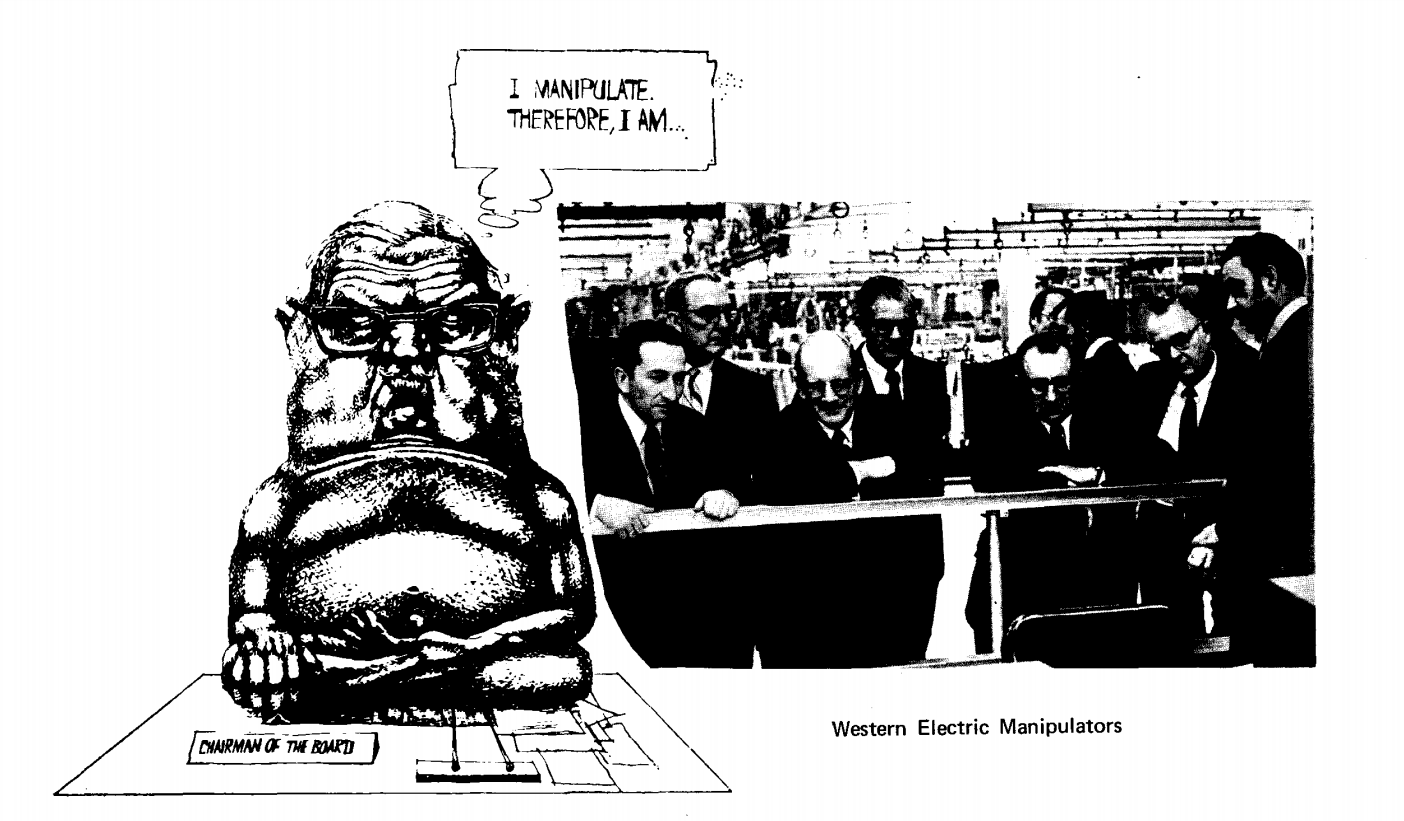

There was but a sardonic humor in that appraisal of the work situation. Management’s search for a solution to the alienation, boredom, and depersonalization of factory workers directed the course of a symposium entitled “The Corporation and the College as Social Engineers” which was staged at Emmanuel College, a Catholic women’s liberal arts college in Boston on the evening of April 25. Participants in the colloquium included a panel of Emmanuel students and faculty, delegates from the Western Electric managerial strata, and a largely student audience numbering nearly a hundred and fifty.

The managers, voicing concern for the problem of worker alienation, discussed particular experiments conducted at Western Electric using motivational techniques. The contribution of the Emmanuel College participants was the following historical critique of practical and ideological programs designed to increase the commitment of workers to the work process.

During the course of the colloquium the managers increasingly antagonized the audience with their distorted view of the work situation at the Western Electric plant. A director of manufacturing interpreted first name familiarity as some sort of affinity between management and the laborer. With regret, a participant recalled the Spanish boy who lost his thumb in a machine accident because the English instructions were incomprehensible. If he hoped to suggest that managers are human too, his audience was unreceptive. They understood why it is that supervisors don’t speak Spanish.

If they had convinced themselves of their own sincerity, their audience was not so malleable. Those whom they did not polarize with their pretentious concern for the worker, they aggravated by their condescending chauvinism.

The Vice-President of Western Electric responded to the disapproval of the audience with a compact speech on the graces of capitalism. His lecture revealed the fundamental premise that the material wealth of the United States is dependent upon the exploitation of the laborer and the impoverishment of underdeveloped countries around the world.

Ultimately, the Western Electric participants conceded that they had no conclusive solutions to the problem of meaningless work. Just as their allegiance to the capitalistic system blinds their perception of its grand-scale effects, so their very position in the managerial hierarchy does not permit them to entertain any real solutions. To ponder such answers would be to obliterate the necessity of their own existence.

— Jeanne Olivier

Power is an innate right of the organization. It is not only inherent but indispensable. For without it how can the organization accomplish its mission, viz. make money for their owners?

Douglas S. Sherwin in Harvard Business Review

In recent months business and popular magazines alike have devoted their pages to the problem of work. Dissatisfaction and boredom at the workplace were prominently featured in Newsweek last month. Work in America, a report to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, examines these problems in greater depth and challenges the view that the work ethic is on the decline and a welfare ethic taking its place. Moreover, corporations are rapidly rethinking and rearranging their traditional methods of control. There are currently numerous experiments in plants which focus upon increased worker participation, enrichment of narrow and dull jobs, and better training for supervisors to deal with problems of workers.

Job dissatisfaction and boredom are not new; in fact, as our analysis will show, they have been around from the beginning of industrialization, but they have often been overshadowed by more immediate material problems like starvation wages and poor housing. So what makes them a recognized problem now? Bored and dissatisfied workers lower productivity and thus decrease profits, thereby hitting the corporate owners where it hurts. Some of the symptoms are high turnover rates (workers quitting and switching frequently), high absentee rates, low output per worker (producing less than they are capable of), and acts of sabotage1 (causing the work process to be disrupted or the product to be defective)2. Such alienation — lack of control over one’s own life, sense of meaninglessness and social isolation3 — is not confined to the most degraded type of work, such as that at the assembly line where workers are forced to act as robots doing fragmented tasks in unending monotony, but it affects other blue collar workers as well and the supposedly more privileged stratum of white collar or office workers.

It is our contention in this paper that after a study of the history and current practice of capitalist corporations, it is clear that any programs designed to increase motivation and commitment of workers to their work, be they called humanization of work or job enlargement, are only instituted to counteract present or future losses in profits—profits which the workers do not own and over whose disposition they have no control. In other words, within the context of the capitalist corporation any improvements in the work environment are only a means to an end, rather than an end in itself. Workers are very sensitive to this and they are resentful of the manipulation which management uses to convince them that they share the same goals, that they are a big happy family in which everyone benefits if everyone does his/her job. But since they have to work in order to eat, workers also often find themselves quite impotent to do anything about this situation. Furthermore, since the purpose of the capitalist corporation, as any manager will tell you, is to make ever-increasing profits for the owners, there are clear limitations on the domain in which workers can be allowed to make decisions. The really important decisions will have to remain .in the hands of a few executives and owners and they require a hierarchical structure, thus emphasizing not merely a division of labor but a clear-cut division of interests.

Social Engineering: An Overview

Organized capitalism and individual entrepreneurs have always had to deal with a resistant workforce which balked against the exploitative conditions to which they were subjected in the factory system. During the first few decades, coercive measures were generally effective to insure the smooth operation of production because of the workers’ extreme need and their lack of experience in organizing themselves. However, in the course of the 19th century, entrepreneurs increasingly realized that coercion had its limitations and that it might very effectively be supplemented with psychological mechanisms that would insure the internalization of the value of hard work to be performed for someone else’s benefit. To some extent this function had already been performed by the Protestant Ethic4. Nonetheless, in an age of increasing secularization, the rising capitalists (then also commonly called the “Robber Barons”) were themselves still greatly in need of justifying their practices; a more up-to-date ideology was required. Herbert Spencer, obliged by providing the “survival of the fittest” theory which had the additional advantage of presenting itself as science. Social Darwinism,5 as this theory is also known, holds that in the struggle for social existence, the strong survive and the weak go under. The strong are also defined as morally the fittest. Applied to the factory, the entrepreneur was obviously the fittest to lead while the workers had to compete with one another to show that they, too, could succeed. This ideology not only legitimated the hierarchical organization but also reinforced individualism, thereby counteracting the combination of workers in unions. Social Darwinism clearly recognized that workers and entrepreneurs were in conflict with one another and that some select few were destined to win.

This ideology ceased to be sufficient in itself when the rapid rise of labor unions forced the capitalists to recognize that their supremacy was being challenged by organized labor. The presumably unfit masses were now banding together,6 rather than competing as individuals, but in the factory all power continued in the hands of the owners. However, the latter were forced to make some concessions. At the beginning of the 20th century, Frederick Taylor presented a new concept: scientific management, also known as Taylorism. Scientific management emphasized the development of precise measures of worker efficiency and the use of piece work, premiums. and bonuses as incentives. The goal was, as ever, to maximize profits by maximizing productivity; and productivity was to be maximized by scientifically determining who was best suited for a particular job and how that job could be done most efficiently. The accompanying ideology, which Taylor believed was even more important than the specific techniques, constituted a considerable deviation from the “survival of the fittest” ideology.

Scientific management, as an ideology, assumed that the new scientific method would create social harmony by showing that both workers and employers in cooperation would benefit from scientific management and that industrial conflict was unnecessary. However, in response to the threat of unionization, Taylorism continued to stress individualism and competitiveness. Furthermore, Taylorism laid the groundwork for the disciplines of industrial psychology and industrial sociology which have traditionally worked hand-in-hand with industrial management. Scientific management emerged in response to other developments, besides militant trade-unionism. For one, companies were growing ever larger, increasingly requiring an administrative bureaucracy run by managers. The streamlining of business practices through the application of Taylorism was merely part of a trend toward greater rationalization of production. In this process the worker was still viewed as just a cog in the machinery which has to be kept running smoothly. The basic assumption behind Taylorism, as in previous theory and practice, was that workers best respond to material incentives, i.e. wage increases in return for higher production.

Scientific management, as an ideology, assumed that the new scientific method would create social harmony by showing that both workers and employers in cooperation would benefit from scientific management and that industrial conflict was unnecessary. However, in response to the threat of unionization, Taylorism continued to stress individualism and competitiveness. Furthermore, Taylorism laid the groundwork for the disciplines of industrial psychology and industrial sociology which have traditionally worked hand-in-hand with industrial management. Scientific management emerged in response to other developments, besides militant trade-unionism. For one, companies were growing ever larger, increasingly requiring an administrative bureaucracy run by managers. The streamlining of business practices through the application of Taylorism was merely part of a trend toward greater rationalization of production. In this process the worker was still viewed as just a cog in the machinery which has to be kept running smoothly. The basic assumption behind Taylorism, as in previous theory and practice, was that workers best respond to material incentives, i.e. wage increases in return for higher production.

By the mid-1920’s the concept of material incentives as the sole means to motivate workers was under heavy fire. Elton Mayo, a professor at the Harvard Business School opened a philosophical discussion and offered a new definition of the worker as a human being, not a robot. He was a chief advocate of the “human relations” approach. Mayo postulated a natural solidarity among workers which took precedence over purely economic interest. This social element, according to Mayo, is nonrational. The worker is a sentimental fellow who seeks the approval of his peers. Only a small elite, the managers, have the capacity to learn to be rational and that makes them natural leaders. The task of managers is to guide workers in how to get along with others, to motivate them and to make them see the wisdom of managerial decisions. The fine art of manipulation was increasingly relied upon by managers.

Under Mayo’s direction the pioneering work7 in the new approach to motivating workers was undertaken at the Hawthorne plant of Western Electric. This study, described below, lasted from 1927 to 1932.8 Its findings were published in the mid and late thirties and they are still today widely applied. The spirit of the human relations school pervades management training today although some modifications have been made, notably in the current experiments with designing more fulfilling work.

By the mid-1950’s the moral and ideological implications of this approach had come to full fruition. William H. Whyte’s critical study The Organization Man points out the logical extension of “human relations” into stifling corporatism and groupism. This concept of the corporation as the big happy family is a form of false collectivization and exploits basic social needs of workers for the ends of the corporate owners. Group adjustment becomes the paramount value rather than social change.

These methods may have been somewhat successful among white collar workers in generating loyalty, but their differential application with respect to blue collar workers has not substantially altered the existing feelings of resentment especially in the latter group. Today these techniques are still used, but given the present level of discussion of worker dissatisfaction, it is clear that management is hard-pressed for new solutions. We will discuss some of those below. First, however, we wish to deal briefly with some of the mechanisms whereby these various methods received widespread acceptance.

Science, Ideology and Education

As the previous exposition indicates, periodic changes in the definition of human nature have been an important means with which industrial management has tried to justify its changing tactics of enlisting greater cooperation from workers. Neither these changed tactics nor the changed views of human nature have evolved in random fashion. Each of these adjustments is clearly traceable to the rise or decline of particular historical social and economic forces which challenged management’s assumed right to make decisions affecting the lives of workers.

This is not to say that the image of human nature, as articulated by the British liberals in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, was abandoned; but considerable modifications were introduced as the interests of the industrialists required it.

Because of persistent problems of motivation, it has now been recognized that humans are not only motivated by the pursuit of wealth and social contact but that intrinsic satisfaction and fulfillment in worth and control over their own lives are even more important’ factors. It is interesting to note, and surely no accident, that these last two elements, fulfillment and control, have been virtually absent from the capitalist view of human nature but that they have precisely ·been at the center of the Marxian conception of human nature as early as 18449. We will discuss in a subsequent section why this addition in particular is bound to cause corporate managers lots of headaches.

Many of these redefinitions were presented in the guise of science, notably industrial psychology and industrial sociology, even though statements on human nature generally fall in the realm of philosophy. This was all the more important since the changing needs of industry, e.g. more complex organization and the resulting requirement for more office workers, competition and pressures for greater productivity, had to be accompanied by changing conceptions of workers. Particularly in the early 20th century when industry needed more literate workers, entrepreneurs quite actively influenced the format and philosophy of the newly emerging high schools. After all, their labor force was to be trained in them. Likewise, industrialists have consistently, and not all that subtly, influenced the policies of universities by serving on the boards of trustees.

Despite the myth that schools and universities are neutral, the ideology that prevails in industry is taught in the schools, and it is also with the help of academics such as Elton Mayo generated at universities. Not only do universities provide the research for social engineering in corporations, but they have been, and are increasingly, apply ing principles of “good” management within their own walls. Universities are subject to cost-benefit analyses; management by objectives is practised in junior colleges; and a university in Boston, Northeastern, actually operates at a profit.

Let us now take a closer look at some examples.

Hawthorne and Beyond

The logic of cost and efficiency express the values of the formal organization; the logic of sentiments expresses the values of the informal organization.

Roethlisberger and Dickson,

Management and the Worker

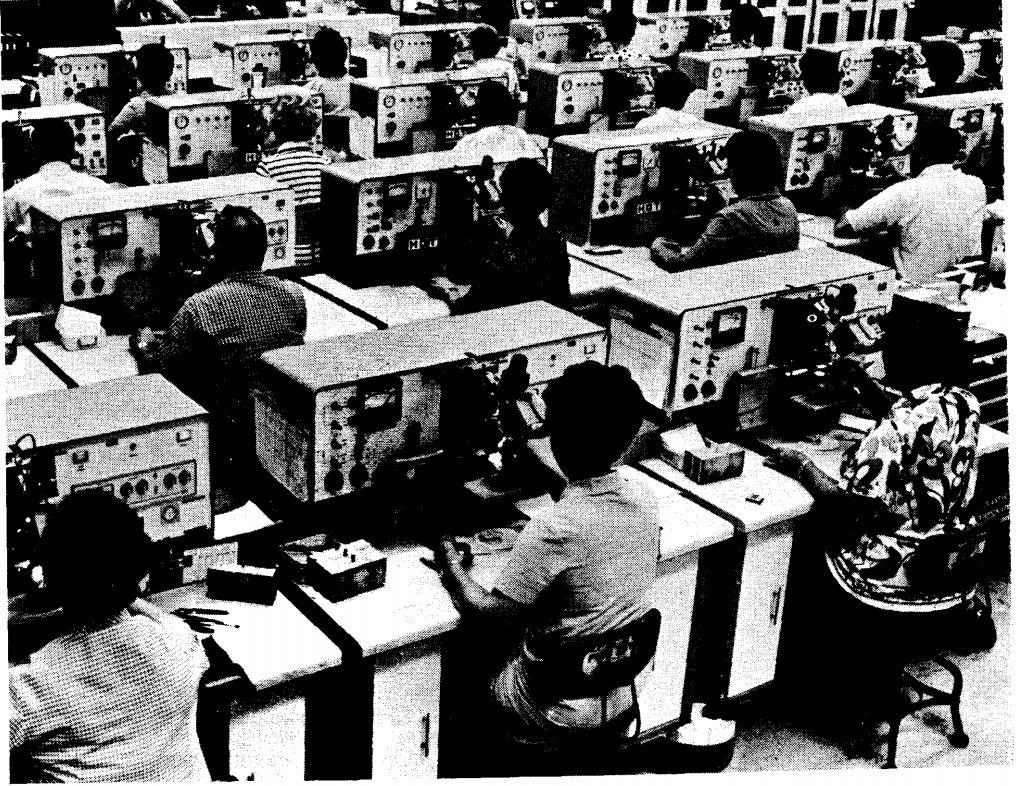

The Hawthorne experiment was originally set up to test the effect of various independent factors of working conditions on productivity. Some of the variables included lighting, humidity, rest periods, diet, length of work day, medical care and wage incentives. The experiments dealt with a small isolated group of six women workers who were removed from their normal work environment and placed in a special observation room, The Relay Assembly Test Room. (The plant made telephone switching equipment.) The most striking discovery of this series of experiments is the “Hawthorne effect” Very soon after the start of the experiment the productivity of these women increased continuously regardless of the variables tested. Even when the variables were removed and conditions in the test room were returned to what they had been at the beginning, their productivity continued to go up. Although the women themselves suggested that this behavior was the result of having no real boss in this situation, this answer was not seen as the crucial factor, and the researchers, Roethlisberger and Dickson, dismissed this observation rapidly. Instead they focused on the importance of paying more personal attention to workers and making them feel more important.

The other classic experiment in the Hawthorne studies is the Bank Wiring Observation Room Experiment, in which a small group of workers forming a complete production unit were set up in an experiment room. The group included 9 wiremen, 3 soldermen, and 2 inspectors; that is, unskilled and supervisory workers. These men were responsible for wiring banks of terminals for switches for central office telephone equipment. Their output and interaction was studied by a social science observer. The men in this unit were paid according to a system of group piecework. The more work the group turned out, the more money each individual worker would earn. The assumption of those who set up this group piecework rate incentive plan was that the workers would work up to the limit set by fatigue to increase individual and group output. As it turned out, however, the workers did not share this view, and they had their own informal rules and norms about how much work to tum out and how to act toward one another:

- Don’t tum out too much work, because that’s “rate busting”.

- Don’t turn out too little, because that’s being a “chiseler”.

- Don’t tell a supervisor anything detrimental to another worker, because that’s “squealing”.

- Don’t try to maintain social distance or act officious. (This applied particularly to the inspectors in the group.)

The men in the Bank Wiring Experiment had set themselves a quota of two pieces of equipment a day, although they could have turned out more. Faster workers would help slower ones; all would work faster in the morning and slow down in the afternoon. In particular the wiremen and the soldermen would switch jobs for a while in order to relieve the monotony of doing a single operation for the entire time, although this violated company rules.

The researchers approached the project with the preconception that “rational” behavior consisted of individual competitive wage maximization even in a group. The workers thought and acted along the lines of a different rationality. They were afraid that during the Depression which was beginning at that time, they might run out of materials and thus be out of a job altogether. Such considerations were thought by the experimenters to be nonrational.10

The lessons of the Hawthorne Studies were many. Although the “Hawthorne effect” is now part of the general vocabulary, the most far-reaching discovery was that of the informal groups within the formal organization structure. One result of these studies was the institution of personnel counseling in the Western Electric Company.

The discovery of the informal group is all important in today’s management practice. Human relations fostering happy motivated workers makes for corporate profits. Sensitivity training and transactional analysis are present-day tools of corporate management. The counseling system is already built in, not quite so institutionally as at Western Electric, but managers everywhere and at all levels require counseling skills. These are all aimed at helping the worker develop an increased sense of self-value and at the same time helping him to look at the corporation as Vital to the survival and happiness of all employees. All social and political problems are thus seen as personal problems amenable to psychological modifications rather than to collective or political solutions. It also shows clearly how the paternalistic conception of the corporation as a big happy family is a logical outgrowth of this approach.

The authors of Management and the Worker do not go into an analysis of such related phenomena as increased sense of freedom, control or self-management, or the lack of discipline (which disturbed observing supervisors and resulted in the removal of two workers), and the increased talking and boisterousness which was eventually forbidden.

Some of these aspects have been taken up by those who are presently planning changed work environments. As mentioned earlier in this paper, some of the current innovations center on job enlargement and more worker participation. Virtually all the experiments in the United States in this area were begun in the 1960’s in response to the realization that the present workforce can no longer be sufficiently manipulated by Taylorism or the human relations approach. Characteristically, job enlargement and worker participation programs have been instituted on a small scale in separate divisions of existing companies or in newly built plants such as a pet food plant in the Midwest.11 In this latter example, a new facility employing 70 workers was organized along the lines of autonomous work groups (teams of 7 to 14 workers and a team leader, collectively responsible for a part of the production or packaging process, including decision making in that area, temporary redistribution of tasks, selection of people for plant-wide committees), integrated support functions (reducing fragmentation of work by having team members share tasks formerly confined to industrial engineers, personnel managers and maintenance works, etc.) challenging job assignments derived from the integrated support functions, job mobility and monetary rewards for learning, facilitation of leadership (eventually teams are to be self-directed, thus possibly eliminating the team leader), access to managerial decision information and self-government for the plant community. What have been some of the difficulties? Major problems arose in connection with deciding differential pay rates within the teams and management at corporate headquarters and in the plant itself has difficulties in accepting its reduced role. Overhead costs, however, have been reduced and production has increased. But it has to be kept in mind that this is a continuous process plant12, that it employs one third fewer workers than originally planned, thus creating even fewer jobs for the community in which it is located, that the product is perceived by the workers as socially useful and that the whole operation is quite small compared to the huge companies in which a large percentage of die labor force is employed.

In another instance management at General Electric in Lynn, where they tried a similar self-structured job enrichment program in the jet engine division, feels that they opened a Pandora’s Box by allowing workers to control their immediate environment. Who is to say what workers will want to control next once they have been given a taste for self-management? Also such an experiment within a plant whets the appetite of those still in traditional jobs. Thus in the case of GE, management is phasing out the project despite the fact that the workers and the union would like to see it continue. It seems that the two approaches, traditional authoritarian and experimental participatory, pose major problems for management if they coexist under the same roof. Hence management’s desire to set the experiments up in new plants or to give clearly circumscribed limited control in the entire old plant.

An almost point-by-point confirmation of our criticisms comes from a rather unexpected source, The Harvard Business Review. Thomas H. Fitzgerald in an article Why Motivation Theory Doesn’t Work, (July-August 1971) clearly states that even job enlargement and worker participation will not solve the problems embedded in the very structure of American industrial organization. Thus, he states:

The subjects of participation, moreover, are not necessarily restricted to those few matters that management considers to be of direct, personal interest to employees, or to those plans and decisions which will benefit from employee advice. Neither of these positions can be maintained for long without (a) being recognized by employees as manipulative or (b) leading to expectations for wider and more significant involvement. Why do they only ask us about plans for painting the office and not about replacing this old equipment and rearranging the layout? (and whether we should be making nuclear warheads or plastic flowers or deodorant sprays? — the authors)

and he goes on:

Aside from the real costs in reduced effectiveness the impact of this new participation on the process and structure of management, though hard to estimate, must be anticipated, because what is really involved is politics, the conscious sharing of control and power. History does not offer many examples of oligarchies that have abdicated with grace and goodwill.

Aside from saying that the problem is structural and requires fundamental changes he has no suggestions to put in the place of current practices. We consider that a rather realistic assessment in light of the fact that Fitzgerald is not willing to propose a complete change of the system.

We would therefore like to state our conclusions.

- We would very much like to see all workers derive fulfillment from their work and control all aspects of their lives including what shall be produced. It is quite possible that temporary improvements can be achieved for some through current management practices but we have no illusions that they will be of lasting effect. The Hawthorne effect will continue to be a major factor in the initial rises in productivity. Very little is known about what happens when the novelty wears off.

- Alienation will be a perennial problem under capitalism because of its requirement of hierarchy and owner control.

- Many industries, especially the automobile industry, do not lend themselves to job enlargement and worker participation, not because the workers are lazy or stupid but because of the inherently meaningless work that is performed in them.

- There is evidence that these new techniques amount to no more than a band-aid approach in response to specific problems. As in the case of General Electric, job enlargement may be instituted during times of union militancy and abolished when the economic situation has changed toward greater unemployment and unions are forced to hang onto what they have rather than demanding more.

- The profit motive which must and does govern the capitalistic corporation is not compatible with true fulfillment of the workers and they are conscious of this.

- Not until human needs rather than production for the profit of the few determine the goals and means of a society can there be real participation and control by the people. It may well be that particularly in this lopsided, overdeveloped society of ours, efficiency and productivity would have to become secondary.

- Liberation from alienation cannot be granted to the powerless by those in power, nor can it be administered piece-meal, it has to be struggled for and won by those without power.

— Patricia Browne, Sheila Cutler, Britta Fischer, Carol Hinchey, & Sarah Vinal

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 4 <<

NOTES

- The word sabotage is derived from the French word for wooden shoe, sabot, which workers threw into the machinery.

- This is not to say that all shoddy products are to be blamed on the workers, for it is well known that built-in obsolescence — factors making for rapid deterioration and devaluation — are intentional in the design of many products and in the use of inferior. raw materials over which the worker has no control. The function of built-in obsolescence is to force the consumer to replace a product frequently, thereby generating more need for its production.

- For a good discussion of alienation in four different industries, see Robert Blauner Alienation and Freedom.

- Max Weber The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and R. H. Tawney Religion and the Rise of Capitalism.

- Richard Hofstadter Social Darwinism in American Thought.

- It is less well known that at that time the entrepreneurs organized themselves in employers associations. With their smaller numbers and greater wealth they commanded influence far beyond the factory gates, and they used their power violently to suppress unions. Much of the information in this section is taken from Reinhard Bendix Work and Industry.

- Mayo was influenced by the writings of Vilfredo Pareto, the Italian sociologist, who influenced Mussolini. “The fascists claimed Pareto as one of their own,” Lewis Coser Masters of Sociological Thought, p. 422.

- Fritz J. Roethlisberger and William J. Dickson Management and the Worker.

- Karl Marx Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. A further fundamental difference between Marx and the English liberals is that Marx did not subscribe to a static, ahistorical concept of human nature.

- George Homans The Human Group p. 64.

- Richard E. Walton How to Counter Alienation in the Plant, Harvard Business Review; November, 1972.

- Blauner op. cit. has shown that highly automated continuous process technology even under traditional working conditions generates less alienation.