This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Agriculture in China: An Eyewitness Report

by Vinton Thompson

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 4, July 1973, p. 26 – 31

Ten SESPA members visited the People’s Republic of China in February and March as guests of the Chinese Scientific and Technical Association. Their four weeks were a very brief introduction to the practice of science under socialism. The possibility of the trip was first discussed in Boston in January, 1972. Collectives for preparation and study — including SESPA people who didn’t intend to go — were formed in Boston and in Stony brook, New York. The delegation was chosen through discussion within the group that responded to a call in the May 1972 issue of Science for the People, on the basis of a balance of qualifications, with political practice and outreach possibilities as dominant factors. The participants are anxious to share their experiences and to speak to SESPA or other groups. They can be contacted through SESPA in Boston.

Their itinerary included universities and other educational institutions, research institutes, health care facilities and productive units such as factories and communes. One of the most important themes in what the SESPA China Collective saw was how Chinese scientists, technical workers and other intellectuals strive to learn to “serve the people wholeheartedly. ”

The section below describes the application of technology in the agricultural field It is excerpted from a forthcoming book by the members of the SESPA China Collective, entitled People’s Science in China.

Throughout the Chinese Revolution, both before and after the victory of 1949, conflicting strategies for consolidating socialism in the countryside, and thus planning rural development, have generated fierce struggles within the Chinese Communist Party. The struggles within the party have in turn reflected underlying social developments in the countryside and in the cities. Particularly since 1949, scientific and technical developments and the uses to which they are or could be put in agriculture have played a key role in these struggles.

. . . . .

The success of people in the less developed countries in achieving development in their interest depends in part on their being able to obtain unity between urban and rural workers. China is a classic example of the success of this strategy. But the differences that have developed between town and countryside don’t disappear with the victory of the revolution. The Chinese are determined to unite the countryside and cities in joint parallel development. To do this they must work hard to counter the spontaneous tendency for industry and wealth to concentrate in the large cities. This is where rural light industry comes in. By encouraging communes and counties to set up small factories, the Chinese are providing the industrial base for the mechanization of agriculture and at the same time countering the dependence of the countryside on the cities. The cities can concentrate on heavy industry requiring large capital investment and the country people meanwhile begin to experience and master the machinery and techniques of modern industry. The Chinese believe that through large scale mechanization the peasants will become agricultural workers, in the same sense that steel workers are workers. As Liu Hsi-yao put it during our Great Hall interview: “In terms of technology there is no line of demarcation between agriculture and industry.”

. . . . .

To set the context for our investigation of the Xigou scientific and technical effort in agriculture, a few initial social and physical facts follow. Xigou People’s Commune has 5,000 members divided into 10 production brigades. Xigou Production Brigade is part of Xigou People’s Commune and has 1,680 members (380 households) divided into 12 production teams and scattered among 44 small villages. The brigade occupies several small and large valleys, lies about 1,500 meters above sea level, and enjoys about 150 frost-free days a year. Though Xigou is not a “rich” brigade, it is unusually “advanced” in some respects. Private plots are a case in point. In most places in China households are alotted a certain amount of land for private pursuits. The size of these plots and the emphasis put on them has been a subject of controversy within the Communist Party, but all seem to agree that they are necessary in most places during the period of socialist transition. Xigou, we were surprised to discover, has no private plots. The people there, we were told, find it more profitable as individuals to till all the land collectively. With this background in mind, we can discuss our interview with the Xigou Production Brigade Scientific and Technical Group. Five of the Group’s members participated in this meeting, including several technicians, an older “experienced” peasant, and a forestry team member. The person responsible for Brigade agricultural output, Kuo Gang-zhu (vice-chairman of the Brigade revolutionary committee) led off the discussion by saying, simply, “We’ve done some scientific research work.” And then he defined the principles that guide the group’s approach: “Science and technology must serve production and serve the people under the leadership of the Communist Party and Chairman Mao.” To illustrate this idea Kuo ran down the history of grain production at Xigou.

Before liberation (1937 in Xigou, which was on the border of the communist held territories during the war against Japan) people grew only about 100 jin of grain per mu. In 1943 some peasants established mutual aid teams in which they helped each other in the fields on a coordinated basis. Grain production rose to about 200 jin per mu. In 1951 mutual aid team members pooled their land and farming implements to form producer’s cooperatives. The cooperatives’ yearly incomes were distributed on the basis of a household’s original contributions of land and implements as well as on amounts of work performed. These cooperatives raised production to 300 jin of grain per mu per year. In 1955 the Xigou cooperatives adopted the principle of distributing yearly income entirely on the basis of work performed. The resulting “advanced cooperatives” achieved a ·grain output of 400 jin per mu per year. In 1958 the advanced cooperatives around the Xigou area merged to form a people’s commune, making possible larger scale water conservancy efforts, and production rose to more than 600 jin per mu per year. By 1969, after the Cultural Revolution, yield had increased to more than 800 jin per mu and in 1970-1971-1972 it averaged more than 1,000 jin per mu, an increase of 10-fold over pre-revolutionary production.

In each of these periods of increased production, social change preceeded and fostered technical advance. Kuo explained that the only way to “improve our scientific research work and make scientific research work serve production is to mobilize and encourage all members of our brigade to take part in scientific research work. It is the only way we can learn about nature in a better and faster way.”

Kuo went on to outline the agricultural effort at Xigou in terms of the “Eight Point Charter” of agriculture put forward by Mao in 1958. In the following paragraphs, we will present Xigou from the vantage of some of the eight points:

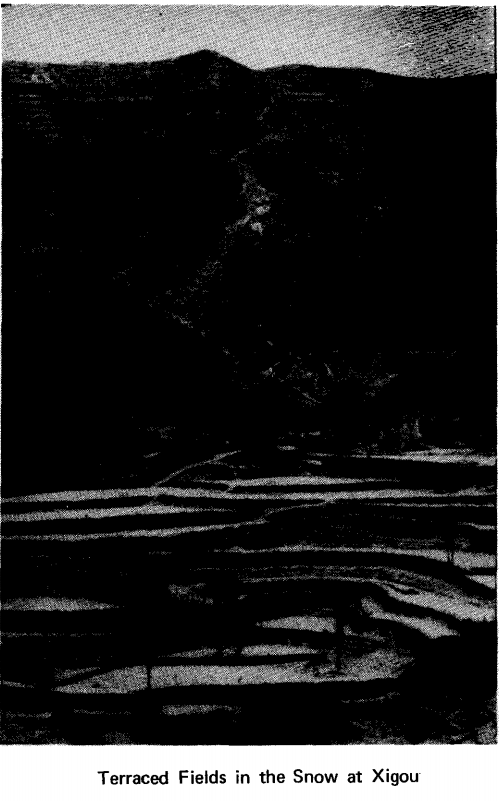

Soil Improvement (T’u). Xigou Brigade occupies an area about 7½ kilometers long and 4 kilometers wide. It is all exceedingly hilly. Most of the crops are grown in small terraced fields held in place by rock walls cut into the hillsides or extending up ravines. Xigou gets only 50 centimeters of rain a year, half of which falls in July and August. There is a prolonged drought from mid-winter through spring. In the past when the summer rains finally hit the parched hills the water ran off quickly, rushing in torrents down the mountain ravines to carry away the soil and crops in the terraced fields along the way.

In this circumstance, Kuo said, “The major task is to hold the water in the soil.” The Xigou people have accordingly developed several farsighted projects which mesh together for one purpose—hold on to the water, hold on to the soil.

Dung Ui-gou Valley, longest of the seven major valleys encompassed by the brigade, may serve as an example of this effort. The valley is 4½ kilometers long and is worked by 32 households scattered in 14 small villages. Since liberation the people of the valley have built 130 dams and terraces and created 30 mu of cropland where no soil at all existed before. On the hillsides above the valley they have forested 300 mu of land.

We drove up Dung Ui-gou valley one afternoon to look at the terracing work. In the part of the valley we examined closely, a rather narrow gulch that had obviously at one time b(;o::u a deeply eroded and worthless gully had been transformed into a neatly laid out staircase of small fields. A narrow rock terrace wall separated each level from the next and after every third or fourth field this wall was about a yard thick and strongly built to withstand the worst of the summer floods. These fields had all been created by hauling in soil from nearby excavations. Xigou has an abundance of loess soil, a very fine-grained yellowish wind-deposited soil that occurs in very thick deposits in the hills of northern China. (Traditionally. the Xigou peasants lived in caves carved in cliffs of this soil.) Easily dug and useful for agriculture, it makes Xigou’s tremendous landfill efforts possible.

These landfill efforts are most impressive on the floor of the main Xigou brigade valley. In the past this valley contained only a rock and boulder strewn riverbed and a road of poor quality. Come the summer rains, the river flooded. By spring it ran dry, and nothing useful grew in the valley bottom. In 1953 the Xigou people built a large reservoir (to be discussed in the next section) and cordoned off the river course below between closely set strong rock walls. On either side of these walls they have now terraced and filled in 500,000 cubic meters of earth, turning most of the valley floor into fields and orchards. In the past, before reforestation and the other water control efforts, it was impossible for one strong person to turn even two mu of riverside land into cultivated fields. It still takes one person three months to terrace and fill one mu of land one meter deep with soil. Xigou has begun to mechanize its landfill operations. While we were there the brigade had three small bulldozers leveling loess hills into a large field; one of these machines they owned, the other two were on loan from the county.

Rational Application of Fertilizer (Fei). Walking around at Xigou we noticed piles of blackish earthlike material set at intervals in the bare plowed fields. These turned out to be piles of fertilizing material, vital for replenishing and boosting the nitrogen contents of the soil. Most of Xigou’s fertilizer comes from human and animal sources in the form of nightsoil and manure. Nightsoil is China’s traditional fertilizer and has maintained the fertility of Chinese fields in the face of hundreds of years of continuous cultivation. Since the revolution the use of manure has increased dramatically with the rapid growth of animal husbandry. In 1952, at the beginning of the cooperative period, there were only 300 sheep and goats at Xigou; now the brigade’s flock has grown to 1300. In the same period pigs have increased 9-fold and now number 300. The brigade also has more than 150 head of cattle and more than 190 donkeys. The Xigou people carefully conserve the manure of all these animals. On one hillside we saw a special cornstalk enclosure where the flocks are gathered together to defecate in one place. The increase in fertilizer is the single most important factor in the increase in yields over the years. For Chinese peasants the trek to the fields each year with shoulder pole buckets of accumulated manure is as much a part of life as plowing and seeding. However there is nothing indigenously Chinese about the uninhibited handling of manure. A former student from the port city of Tientsin, balked when first confronted .with the task of carrying goat manure, because she thought the manure was just too dirty to handle. But, she told us, she went through a mental struggle and finally “realized that this was a petty-bourgeois idea.”

Rational Application of Fertilizer (Fei). Walking around at Xigou we noticed piles of blackish earthlike material set at intervals in the bare plowed fields. These turned out to be piles of fertilizing material, vital for replenishing and boosting the nitrogen contents of the soil. Most of Xigou’s fertilizer comes from human and animal sources in the form of nightsoil and manure. Nightsoil is China’s traditional fertilizer and has maintained the fertility of Chinese fields in the face of hundreds of years of continuous cultivation. Since the revolution the use of manure has increased dramatically with the rapid growth of animal husbandry. In 1952, at the beginning of the cooperative period, there were only 300 sheep and goats at Xigou; now the brigade’s flock has grown to 1300. In the same period pigs have increased 9-fold and now number 300. The brigade also has more than 150 head of cattle and more than 190 donkeys. The Xigou people carefully conserve the manure of all these animals. On one hillside we saw a special cornstalk enclosure where the flocks are gathered together to defecate in one place. The increase in fertilizer is the single most important factor in the increase in yields over the years. For Chinese peasants the trek to the fields each year with shoulder pole buckets of accumulated manure is as much a part of life as plowing and seeding. However there is nothing indigenously Chinese about the uninhibited handling of manure. A former student from the port city of Tientsin, balked when first confronted .with the task of carrying goat manure, because she thought the manure was just too dirty to handle. But, she told us, she went through a mental struggle and finally “realized that this was a petty-bourgeois idea.”

In addition to nightsoil and manure Xigou brigade uses some “vegetable fertilizer” like sorghum straw and buys. a little manufactured fertilizer from the government. It also maintains a very remarkable “local fertilizer” factory as an annex to the local school.

This factory makes “5406 powder,” a bacterial product that is mixed with soil. and applied to fields as fertilizer. In addition to its function as fertilizer, the mixture is reported to help crops absorb nitrogen, protect them against more than 32 bacterial diseases, and promote speedier seed germination and a shorter growing period. To make the powder the factory technicians (it appeared there were three) prepare a medium which includes potatoes, sugar, bran and agar. Live bacteria are smeared on this medium, grown for several days in a warm room and then the bacteria are collected, dried, and mixed with earth, 1:12, to make the final product.

It appears that small factories producing microbial products are now common in the Chinese countryside. We asked about the history of the project at Xigou and found that the school originally took on the project as part of a larger effort to make scientific education serve production. They first heard of the process when the Southeast Shansi District had a meeting at which someone from the Changchih school spoke about making bacterial fertilizer. To learn the process they sent two people to Changchih (which is the largest city in southeast Shansi) to attend lectures and practice techniques for four or five days. Since mastering the art, Xigou has in turn taught bacterial fertilizer making to people from about 20 other communes. Similar processes of face to face contact and exchange appear to be exceedingly important in the transmission and popularization of science in China.

Building Water Conservancy Works (Shui). Two large dams and reservoirs are the keys to Xigou’s water conservation and flood control program. The first of these reservoirs lies above the reclaimed valley bottom land we mentioned earlier and was built in 1958 during the Great Leap Forward period of commune formation. During this period the commune “paid great attention to the local militia” as a collective force for socialist construction. The militia themselves designed and built the dam which is earth covered with stone and is 100 meters thick at the base. They completed it in less than a year by day and night work. Written in stones on the face of the dam is the inscription “Militia Fighting Reservoir.” The reservoir itself has a capacity of 1,700,000 cubic meters of water.

The second reservoir stands further up the main valley and represents an even greater human effort. It is known as “Xigou Prepare-for-War Reservoir.” Inspiration for its construction came from the county (Ping Hsun) after serious water shortages and a bad drought in the 1960’s forced the area to import water. After the county decided the project should be undertaken the work of building fell to Xigou Brigade itself, the main beneficiaries. They had help with the design from the county department of hydraulics, and commune militia pitched in to help with part of the work, but the brigade did most of the work and footed the bill.

The dam is solid stone (33,136 cubic meters worth) and measures 178 meters long by 25 meters high. The entire dam was built without heavy machinery. A gravity powered cable operation brought stone down from mountainside quarries. The reservoir has a 615,5000 cubic meter capacity and receives most of its water from the rainy season runoff. It has solved the problem of year round drinking water for 1 0,000 people and 5,000 animals. In addition to Xigou it serves three other communes, eight production brigades, and a few small factories. It also is the focus of Xigou’s irrigation program. Below the dam three canals (with a total length of 12.5 kilometers) branch out to deliver water along the hillsides of the valleys below. In about a year, when side canals from the three trunk lines are completed, Xigou will be able to irrigate 1 ,000 mu of land or two-thirds of its cultivated area. In concert with other improvements, this is projected to lead to yields of 1,500 jin of grain per mu by 1975, an increase of almost 50% over present levels. The reservoir itself now contributes fish to the brigade food supply. It was stocked by the district fish hatchery in Changchih and people fish with nets to haul in 4-5 pound carp in an area which never had fish before.

The Xigou people also depend to some extent on wells and ground water, a source of water which has also increased in capacity as the reservoirs raise the local water table. Finally, they see each other and every field as a small reservoir during the rainy season. Following the slogan “keep the water in the dish” they build the edges of each terraced field a little higher than the center so that it slows down and retains the water passing through.

Popularization of Good Varieties (Chung). The introduction and development of new crop varieties has formed a major part of Xigou Brigade’s scientific agricultural effort. Traditionally, Xigou relied for its maize on two local varieties which yielded poorly. Since the mid-sixties the brigade has experimented with a new technique of producing hybrid corn which involves crossing two “pure line” varieties to produce seeds that grow into plants bearing genes from each parental variety. The result is often a much higher yield. Each year the same cross must be repeated to get seeds for the next year. Such a complex breeding system requires effort and planning that would be impossible in a peasant economy without the collective system of the communes, brigades, and work teams.

Since 1958 Xigou Brigade’s self-produced hybrid corn has yielded a harvest equal to that of the more temperate climate and fertile soil of the lower Yangtze River area.

Rational Close Planting (Mi). For some time in China, close planting, the practice of sowing seeds densely, has been a subject of much debate. As the cooperatives and communes began to transform miserably poor farmland into productive land the peasants still tended to sow the low densities of seed appropriate to sparse growth under the old conditions. The new fields, with more water, more fertilizer, and higher producing varieties could support much denser stands of plants, and it became important to adopt new seeding densities to achieve the highest possible yields.

Rational Close Planting (Mi). For some time in China, close planting, the practice of sowing seeds densely, has been a subject of much debate. As the cooperatives and communes began to transform miserably poor farmland into productive land the peasants still tended to sow the low densities of seed appropriate to sparse growth under the old conditions. The new fields, with more water, more fertilizer, and higher producing varieties could support much denser stands of plants, and it became important to adopt new seeding densities to achieve the highest possible yields.

There are however limits to close planting as a technique for increasing yield. Under the old conditions denser seeding often increased production, and with improved conditions during the 1950’s more surplus grain became available each year to be used for the next year’s crops. As conditions did improve and individual plants grew larger and stronger and needed more space, a counter tendency set in. In some cases seeding too densely began to reduce total yields. Evidence that in some places the enthusiasm for close planting got out of hand is illustrated in the following passage from a December 1972 issue of Peking Review. It discusses the resolution of a small conflict over close planting at Tachai Brigade and is an interesting example of the respect scientific experiments have. gained in the eyes of China’s peasants.

Last year the question arose as to whether maize should be planted close together or more spaced out. A few years ago, the answer would have been the former. But now opinions differed. Some people said: “Close planting was certainly necessary when our land was poor. Now that it’s more fertile, the plants would grow much too big and dense for the air and light to get through. Yields will surely suffer then. ” Comrade Chen Yung-kuei, secretary of the brigade Party branch, was of this opinion.

However, another Party branch committee member who disagreed challenged the others to a contest. In spring he planted maize the way he thought best in a plot next to Chen Yung-kuei’s experimental one. The ears of maize on his plot came out small, and the stalks thin and the leaves sparse. People predicted failure but he refused to admit defeat. “The ears may be smaller,” he thought, “but there are more of them. Who knows who’ll win in the end?” Autumn harvest came, and his plot, the same size as Chen Yung-kuei’s, produced 100 jin less. He was finally convinced.

Innovation in Farm Implements (Kung). The mechanization of agriculture has been a major topic of debate in China’s development. While there was agreement that mechanization ultimately was essential, one faction favored delaying it until heavy industry could be established. As Liu Shao-chi argued for this position, in the 1950’s:

Only with nationalization of industry can large quantities of machinery be supplied the peasants and only then will it be possible to nationalize the land and collectivise agriculture.

An opposing faction, led by Mao argued as follows:

In agriculture, with conditions as they are in our country cooperation must precede the use of big machinery … therefore we must on no account regard industry and agriculture, socialist industrialization and socialist transformation of agriculture as two separate and isolated things, and on no account must we emphasize one and play down the other.

Otherwise, he argued, the natural inclination of the peasants toward petty entrepreneurism would redivide the countryside into exploiting and exploited classes. This would slow down the development of agricultural production and cripple efforts in large industry by choking off its supply of raw materials, thereby completely undermining the basis of the socialist state and making the long term mechanization of agriculture impossible.

In this struggle, initially behind the scenes, Mao’s view eventually prevailed. Later, the issue became part of the mass debate and struggle of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s.

At Xigou Brigade, mechanization now means six tractors and two trucks. Before liberation and cooperation all burdens were carried on shoulder poles down narrow paths; now trucks run on hillside roads built during the Great Leap Forward. In the past (using oxen) it was difficult to cultivate more than the first few inches of soil; now, their tractors plow to a depth of .8 to 1.0 foot. They have also introduced machine threshing and set up a small factory to process their crops. One small group of workers has picked up the skills needed to repair farm tools and machinery and the brigade can even build its own electric motors.

. . . . .

Perhaps the most impressive single program at Xigou is the brigade reforestation program. During the brigade’s early years, the leadership of Li Xun-da, a prominent political figure in Xigou, had been tied closely to the reforestation program. Li Xun-da, vice-chairman· of the Shansi Province Revolutionary Committee, and· member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, had been a key person responsible for transforming the mountain regions into ” a new village of socialism.” He accomplished this by first creating mutual aid teams to reclaim the land during the 1942 drought period. Since these teams were so successful in 1951 Li led in the formation of an agricultural cooperative which even in its first year reaped a bumper harvest.

The reforestation project began in 1953, in the midst of the struggle over cooperation. Li Xun-da and Xun Da-lai (labor heroine and assistant secretary of the brigade Party branch) led some cooperative members in seeding 300 mu of barren mountain side with pine and cypress. Much controversy proceeded this action. Many old people argued that it would be better to plant willows and poplars which would grow quickly and yield benefits before they died. Pines, they said, would take 100 years to grow and cypress 1 ,000. But they were countered by people who pointed out that willows and poplars, water loving plants, would not grow at all on the dry hillsides and that pines and cypress yield more useful wood. Another line of opposition came from people who thought that no trees at all would grow on the Xigou hills. If it could be done, they argued, our forebearers would have reforested the land.

The results of the first year’s sowings seemed to support the dissident viewpoints. Only about 10% of the expected seedlings grew. But Li countered that 10% wasn’t a dismal failure and at least positively showed that trees could grow on the slopes. He encouraged people to learn from their mistakes, analyze reasons for the setback, and move forward.

The results of the first year’s sowings seemed to support the dissident viewpoints. Only about 10% of the expected seedlings grew. But Li countered that 10% wasn’t a dismal failure and at least positively showed that trees could grow on the slopes. He encouraged people to learn from their mistakes, analyze reasons for the setback, and move forward.

To this end the brigade sent a member to study the experience of other cooperatives with more experience planting trees. They learned that successful reforestation requires that the area to be seeded be blockaded to animals; grazing animals eat young trees. At Xigou itself the peasants decided that most seeds had been planted too deeply to germinate or so shallowly that they had been killed by the sun. It also appeared that many had been devoured by birds and insects. So the problem, they decided, was poor management of the seeding operation, not impossible physical conditions.

The following year the Xigou people tried again using their new knowledge. This time the planting succeeded, and since 1954 all the Xigou people have taken part in the reforestation.

There are now about 30 mu of pine and cypress for each household in the brigade (or more than 2,000 timber trees each). This represents a cash value of about 10,000 yuan ($5,000). In five years the value of the timber will have grown to 10,000 yuan per person. In China, where 1,000 yuan a year is good pay for factory work, this represents a tremendous capital accumulation, and a very great collective economic achievement. It is also an important gain for the national economy in a country which inherited severely limited forestry resources at the time of the revolution. In the early 1950’s only 8% of China’s land area was forested as compared to 34% of the land in the Soviet Union and 33% of the land in the United States.

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 4 <<