This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

The US Ethical Drug Industry

by Jon Felthelmer

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 4, No. 4, July 1972, p. 12 – 14 & 28 – 33

The prescription drug industry, with the complicity of protecting and supporting institutions of its corporate capitalist complex; the government and the FDA, the doctors and the AMA, the advertising media, has made the technology of drugs and health care a destructive one, a technology designed to promote the best interests of a small elite in lieu of, and at the expense of, the majority of people. There is a direct link between market structure and the shape that this technology does and must take, a cause and effect between corporate capitalism and a repressive scientific estate.

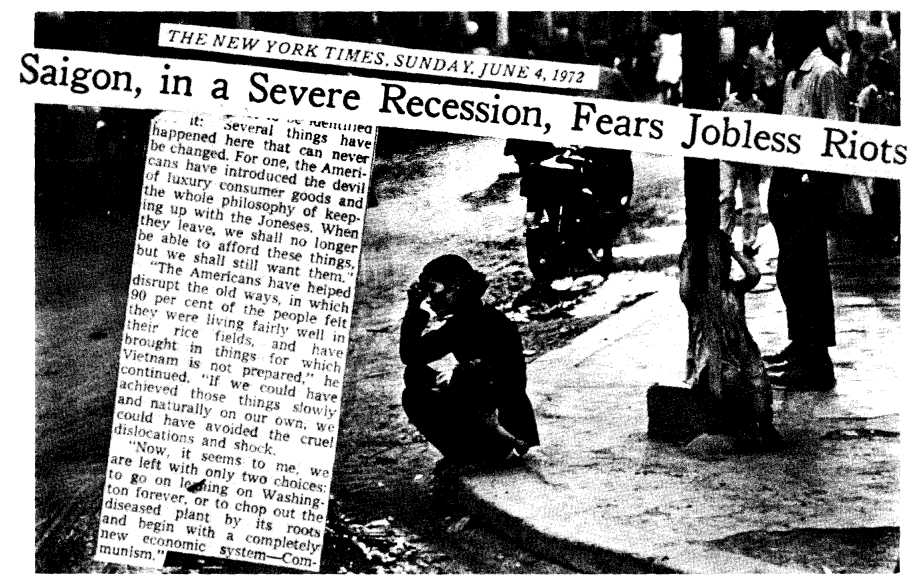

When discussing the drug industry, it is important to distinguish it from other industries. First of all, the demand for drugs is inelastic, drugs are needed regardless of the price, and even when people have very little money as in times of depression, the need for drugs is still the same. Note that the profits of many drug companies in times of depression, have been as high or even higher (lack of money for food and inadequate living conditions leading to illness) as in normal times. Thus, when demand is inelastic, there is much room for exploitation, the idea of charging as much as the market will bear.

Drugs are often matters of life and death; the use of an unproven or untested drug can obviously be dangerous. What must also be seen as dangerous is the use of an ineffective drug. To substitute a drug mistakenly believed to be efficacious for another cure or even bed rest will often lead to a worsening of the condition or even death. Take, for example, the case of Altador (furaltadone) of Eaton Laboratories, a division of Norwich Pharmaceutical Company, which was offered for use against infection, and when used by patients with severe staphylococcal infections might well have led to mortality from lack of effective treatment when efficacious drugs were available.1 The unnecessary or over-use of a drug may also lead to unforseen results. The rash prescribing of antibiotics to combat even the common cold (useless) and minor infection (unnecessary) in the 1950’s resulted in resistant strains of bacteria-like invigorated staphylococcus which caused epidemics between 1954-1958.2 It is the industry that fosters the overust of drugs, through heavy and often false advertising. The problem is compounded by the fact that the consumer of drugs is not the purchasing agent. The doctor who makes out the prescription decides what drug and from what company (unless generically prescribed, which is not often the case) and with the current anti-substitution laws, this is the drug the patient receives.

The drug industry is by examination of its own data, an oligopoly. Although the Pharmaceutical Drug Industry says that “the US drug industry is one of the least concentrated of all American industries… government figures show 1325 firms in the drug industry,” by its own figures, the twenty largest companies account for over 75% of new drugs prescribed. It also shows the four largest firms accounting for 38% of the same.3 Yet these figures underestimate the real concentration of the industry. It is necessary to divide the total market into specific markets determined by the drugs themselves. In recent government anti-trust actions, this has been the case. The merger between Continental Airlines Inc. and Western Airlines was blocked by the Civil Aeronautics Board because it was determined that these would be a monopoly in the specific Pacific airline market.4 The merger between Proctor and Gamble, Co. and Chlorox was blocked by the federal trade commission (supported by the Supreme court of the US, 1967) because it was said that there would be unfair concentration in specific markets.5 Relating this to the drug industry, the leading five firms in twenty therapeutic markets accounted for between 56 and 98% of sales.6 In eight out of nine sulfa drug markets, one firm accounted for 100% of sales, and in only six out of the 51 products were there more than four competitors.7

As Bernard D. Nossiter said, in the Mythmakers “there is nothing in the logic or practice of concentrated corporate industries that guides or compels socially responsible decision making.” Nothing supports this better than the developments in the drug industry. Before, and during World War II the structure of the drug industry was such that there was a fairly small number of well established firms competing in a limited number of areas in which the technology had long been completed, what we might call products of “old technology.” These firms .mostly engaged in a defensive research, designed to keep the company abreast of developments in areas where they had products to protect rather than designed to open vast new areas. The firms had profitable and stable product lines that were insulated from the pressures of technological competition. In 1947, these “old technology” drugs still accounted for more than 80% of ethical sales, and two-thirds even up till 1954.8 Certain firms, like Pfizer and Merck, were bulk manufacturers of drugs who sold to other drug makers who repackaged and relabeled the drugs and then retailed them. For a while this was very profitable. Yet after the war new entries especially into the penicillin and streptomycin markets was caused by a readily-acquired technology. This increased price competition, dropped prices to the marginal cost level (i.e. eliminated excess profits) and caused excess capacity.9 From this point on, the shape of technology within the industry completely changed. The firms that were hurt the most by the new competitive pressures were the first to adopt new “offensive” research postures, with growth as the main rule. The impetus was to create new markets, yet also to create technology and economic control together in order to secure a strong market position. As the “new technology” firms began to make great sales and profit advances, especially in antibiotics and the postwar miracle drugs, the oldest established firms, such as Lilly, Abbot and Parke-Davis raised their research expenditures from 4% of sales dollars, recognized to be “defensive” research, to 8% and above.10

The “new” technology can best be described as leaning heavily towards “applied” research, the attempt to create many new products slightly differentiated from others, and to exploit the minor differences in the marketing strategies with advertising and other forms of non-price competition. Molecular manipulation, duplicating the molecular structure of new drugs or synthesizing variations of compounds in the hope that one of them will prove pharmacologically active, became the rule. An example would be the adrenal steroid hormones, which were altered by molecular manipulation to reduce the actual milligram weight of the pill, but with no change in the efficacy or side effects. The “new” drugs were prescribed and distributed anyway, to “protect” the patient from side effects.11 This is not to say that “applied” research has no socially benefical purpose. It may be pointed out that, for example, adrenal cortex steroid compound A is useless, while cortisone derived from it through applied research is a most important drug.12 It is also not suggested that basic research has been completely abandoned. Yet when a new drug breakthrough is accomplished, imitations from this creative technology closely follow, as the tetracycline-aureomycinterramycin cycle suggests.13 Even big business apologists, such as Schumpeter, recognize the “creative destruction” of old products and old markets at a furious pace.14 Inevitably, research is used systematically as a competitive weapon, where more research guarantees more sales. Professor Dale A. Console, formerly medical director at E.R. Squibb, puts it this way; “The problem arises out of the fact that they (the drug companies) market so many of their failures. Between these failures, which are presented as new drugs, and the useless modification of old drugs … most of the research results in a treadmill which moves at a rapid pace, but goes nowhere. Since so much depends on novelty, drugs change like women’s hemlines and rapid obsolescence is simply a sign of motion, not progress as apologists would have us believe… I doubt that there are many other industries in which research is so free of risks. Most depend on selling for their successes. If an automobile does not have a motor, no amount of advertising can make it appear to have one. On the other hand, with a little luck, proper timing and a good promotion program, a bag of asafetida with a unique chemical side chain can be made to look like a wonder drug. The illusion may not last, but it frequently lasts long enough. By the time the doctor learns what the company knew at the beginning, it has two new products to take the place of the old one.”15 It is significant that the industry does only 30% of the total research done in this country, and only 10% of the research considered to be basic, where and immediate pecuniary reward is not expected.16

There are certain structural factors internal to industry and external institutional factors essential to the “new” technology. One was the forward and vertical integration by the industry into retail pharmacy and hospital markets, i.e., the inclusion of research, production, and marketing under one roof, thus eliminating the wholesaler. This, along with the closing of competition from imitations of packagers or integrated firms under licensing agreements led to a direct control by the firm over pricing. Patent protection also insured the firm that if it could make a fairly creative modification, it could be the sole seller of it for seventeen years. Product differentiation, under these circumstances, flourishes, its effect on scientific progress is easily seen. P.M. Costello, in his paper “Technological Progress in the Ethical Drug Industry”,17 studied a sample of 528 new drugs between 1945-1965; drugs of new chemical structures excluding combinations of old drugs and new dosage forms, which are sounded on the assumed lower order of scientific ability. Progress is defined where improvements over earlier drugs occurs, anything from less side effects to major breakthroughs. Non-progress occurs when a new drug does not exhibit any improvements over earlier drugs. The drugs were rated as to their technical efficiency relative to a particular problem, and no weight was given to sales volume (no disparity between a drug treating a disease of high incidence as compared to one treating a disease of low incidence). Of the 528 new drugs, 465 of them represented product differentiation, (innovations of no progress) and only 63 represented advances or technological progress.

There is considerable debate on the correlation between structure and performance in industry. One main argument put up by Schumpeter is that only firms with some degree of market power have the resources to innovate (in this case innovate suggests technological progress). This is countered by the theory that innovation is a means for competitive firms to escape the rigors of competition.18 Yet we can compare progress under different market structures. To examine the role of patents, which assure a market position, a position of considerable market power, let us look at the findings of the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly’s investigation. These findings list the origins of basic drug inventions that constitute breakthroughs (basic research) according to the commercial/non-commercial classification, and the existence of patent protection. A great number of the US discoveries, such as the Salk vaccine and bacitracin were funded and developed outside of the commercial sector, by public agencies and institutions. The US discoveries, even including those from the non-commercial sector in all product categories besides antibiotics, are easily surpassed by discoveries in those foreign countries which do not award patents on pharmaceuticals.19 Thus, we can see that patent protection is no guarantee of innovation, nor is its absence a barrier to invention.

If we examine the antibiotics market, it can be divided up into the narrow spectrum market (the competitive segment) and the broad spectrum market (the monopolized segment). Between 1945-1965, 30% of new drugs in the narrow spectrum market and 50% of those in the broad market represented technological progress. Yet the total of new drugs introduced in the broad spectrum market was four, as compared to 34 in the narrow market.20 Thus, where competition remains a force innovations of significance continue. In the broad market, only when the basis of monopoly is threatened by competition is research resumed. As an example, in 1945 Lederle quit its antibiotic research after its discovery of chlortetracycline. It resumed the research in 1952 when Pfizer discovered tetracycline and threatened Lederle’s hegemony.21

That research and development in the pharmaceutical drug industry is concerned with new products rather than new processes in an attempt to achieve scientific or chemical product differentiation can best be explained through the use of profit and price theory under oligopoly. Under perfect or normal competition, where economic profits are minimal or non-existant (economic profit means profit over all costs, including opportunity cost of investments), new processes that cut costs puts the firm in a good competitive position, they allow him to stay in business. Under oligopoly, non-price competition is the rule, with cooperation, price leadership and division of markets. With the competition between products at the same or similar levels, the need is to keep innovating products, rather than processes. To fall behind is to lose demand and thus profits. Of course, it is price competition which is the biggest threat to the corporate establishment. Any large firm would rather grant a license to another large one rather than to the small ones who might introduce price competition. Pricing agreements, patents and advertising act as barriers to entry of small firms. It has been a popular theme of the corporate giants to discredit the research facilities and the quality of the products of the smaller firms. William S. Comanor found economies of scale in research at the lower end of size distribution of firms and diseconomies (increasing cost or inefficiencies) with the movement to larger firms. The larger firms employed a high ratio of supporting personnel to the professionals in the research staff, which was not significant for technological progress. As a whole, the percentage of the research staffs holding doctoral degrees in the industry was only 38%, as compared to 55% in government and 91% in universities and research institutes.22 Firm size did have a positive correlation with research and development output, and also with the expected gains from research. Thus, for the large firms research input equals a product output and expected gains within a reasonable time.

We might also look at the bureaucracy of the corporation to provide insight on the technology of the drug industry. In any large corporation, the timing of a decision may be more important than its correctness. Professor Galbraith maintains that the corporate planning process is such that at certain critical points, it may be better to make a wrong decision that can later be overcome than to disrupt the organization by making no decision at all.23 Thus, there is pressure to research and market at the earliest date, without regard to social responsibility, as apologists would have us believe. Rather than being scientists, the researchers for the corporations are businessmen. Their dedication is to the company, not to scientific advance, their goal is to have have the fruits of their experiments produce a profit for the company. Examination of the drug industry in the USSR exposes a powerful contrast. Promotional costs are minimal, and research is done by government-sponsored institutes without wasteful duplication of research facilities or products, yet prices are high and new drugs are slow in being marketed. Because of the separation of research and industry in the USSR, delays arise because of communication and coordination problems. Research accomplishments are not put into production rapidly. The fact that promotion is so minimal has created a void in any dynamic method for disseminating information. The Russian “Medical Worker” of April 4, 1961, reported, “Information about new drugs is given irregularly so that practicing physicians do not know about them and are deprived of the possibility of using them. The process of replacing oldfashioned drugs by new and more efficient ones is too slow .”24 Thus, our excessive advertising seems to have some social purpose. The Russian system also separates quality control, or post-production testing, from the industry. Because of this, there is a lag between government approval and the availability of the new drug. If we compare the Russian model against our own, it is necessary to weigh the social costs of the two arrangements. In the US 15,000 new mixtures or dosages are produced a year, of which 12,000 quickly die off as useless or dangerous.25 Great pains are taken to market drugs thoroughly, often with the result of the patient in the role of guinea pig. In Russia, there is a time lag in the marketing of new drugs, with testing done thoroughly and great importance placed on the prevention of drug tragedies such as thalidomide. It seems apparent that the Russian system, with all its problems, is at least aware that it is people who are the final users of its drugs.

With the technology of product differentiation and competitive creativity, advertising and promotional activities become very important. The product that is merely “new” can only be sold if the consumers can be convinced that the “newest” is the best.26 Doctors, the purchasing agents, are swamped by brand-name advertisements, promising cures for certain afflictions and often failing to note side effects. An example of this misleading of the public is the case of Mer 29, whose manufacturers failed to note its serious side effects when applying for a New Drug Application. This was done in order to get it on the market (where again its side effects were not advertised) to recoup its research and development costs. This was all done with the cooperation of the FDA, whose medical examiner Dr. X. Talbot said of his decision to approve the application, “I released the drug with the knowledge that things might happen later which were not obvious at the time.”27

Doctors often do not even know the generic name for the drug they prescribe and rarely know the price variations. Thus, only 10% of drugs are prescribed generically, while prices for brand-name drugs are on the average 2/3 higher than those prescribed generically, and that same differential applies for drugs sold by the 33 largest companies as opposed to the remaining 500 examined.28 High advertising often misleads the public and their purchasing agents, but also leads to both high profits and higher costs; and since profits are figured over costs there is a double effect on price. Any firm cannot just double their advertisements and thus double their profits. Yet those firms with higher optimum advertisement expenditures will and do earn higher rates of return than those firms in less advantageous positions.

Advertising plays an extremely important role in the drug industry as a barrier to entry. The advertising to sales percentage in the drug industry was 10%, not including the salaries to detail men.29 Most estimates of the total advertising to sales percentage are about 24%. The next highest industry was the perfume industry (15%) while 25 of the 41 industries examined were below 3% and eight others were between 3%-6%.30 The high concentration of the industry means a price advantage in advertising more because advertisers give discounts for larger quantities of advertising. The new entrant must pay high advertising rates, must spend a high actual cost to promote its product or have it accepted by the consumer, yet must spread its costs over fewer units sold, thus perpetuating a-vicious cycle.

While the drug industry argues that the huge costs of the detail men are necessary to get information to the doctors, it seems as if the public is paying for the costs of its own exploitation. Dr. Harry F. Dowling says, “It has been said that the majority of practicing physicians obtain their first imformation about a new drug from a detail man. From extensive personal experience I can say that is neither necessary nor desirable. Speed is not an important object in most cases, since most drugs that are newly marketed do not represent .anything new. When a drug is really new. information about it spreads with rapidity by word of mouth among members of the profession and through articles in medical journals.”31 Yet it seems as though most of the medical profession is extremely willing to befriend the industry. Only 15% of doctors receive the Medical Letter, which systematically and scientifically examines new drugs.32 All receive the government-subsidized journal of the AMA which is heavily advertised by the drug industry. Thus, the people are again paying for their own exploitation. In the 1950’s, the AMA and the drug industry had realized that an alliance against any socially-responsible health plan was to their own best interests, and the AMA quickly reversed its previously more responsible position.33 Doctors have other self-aggrandizing ends in mind when they support the drug industry. Often they are paid for their help in the testing of drugs. Sometimes the payment is only a luncheon, the invitation to present a paper on the drug, prestige, or an appeal to the doctor’s ego (“your have been chosen to test… “). The doctors realize no prestige will come to them by publishing negative papers. It should also be pointed out that seven out of ten doctors invest in drug companies.34 With this in mind, it is no wonder that they have failed to make any great demands on the industry to be more socially responsible, demands which would mean declines in profits.

The public media has also been extremely helpful to the drug industry. In many cases it has engaged in market-building publicity even before the FDA had acted on a new drug application. Arthur J. Snider, science editor of the Chicago Daily News, in October, 1963, said, “My concern would show that 90% of the new drugs we have written about have gone down the drain as failures. We have either been deliberately led down the primrose path or have allowed ourselves through lack of sufficient information to be led down the primrose path.”35 The news media has not moved nearly as quickly to cover stories such as Kefauver’s uncovering of drug industry abuses. “It is encouraging to be able to record the interest now expressed in drug marketing problems by such conservative newspapers as the Wall Street journal,” said John Lear in the Saturday Review of September 5, 1964… ” But it may be asked where were the potent organs of the daily press when the drug-makers were pulling political and economic strings to try to prevent the facts from being exposed.”36

The results of what has been discussed here, the structure of the prescription drug industry and the scientific estate within it, are high prices to the consumer and high profits for the industry. Although Dr. John M. Firestone, Economics Professor at the City College of NY, in an index of prescription medicine prices showed that they have dipped 8 to 10% since 1960, he. also stated that “An index cannot tell us whether a price is too low.”37 Dr. Whitney, appearing before the Senate Subcommittee on Competitive Prices said that the price of a drug must be weighed in terms of alternative treatment. If a $5.00 prescription will save $100 worth of hospital bills, it is a reasonable price.38 Besides being poor economics, neglecting any link between production costs and price policy, this statement also neglects the social responsibility of the drug industry. Smith, Klein, and French’s drug thorazine on which they did no research was shown to be priced many times higher in the US than in other countries. There is a tremendous difference between drugs sold by bidding to hospitals and government-run projects as to retail pharmacies. There is also a large difference between drugs sold by one company to different cities and countries. In some cases, drugs sold to other countries, even including tariffs, are sold at lower prices than are sold to domestic pharmacies. Penecillin-V (Eli-Lily Co.) was produced in the US and sold in the US to druggists at $18 per 100 125 milligram tablets. This same product was sold to retailers in Australia, Mexico, Venezuela, and Panama at between $10.75 and $15.0039

The drug industry has continually been a high profit industry in comparison to other industries. Overall corporate profits in 1970 fell on the average of 8% while the drug industry’s profits may increase by that same percentage.40 Profits in 1965 given by the Pharmaceutical Drug Industry were 10.8% of sales and 20.3% of investment.41 Between 1954 and 1966, 75% of the five leading manufacturers exceeded 15% profits relative to sales. None of the eight largest ever fell below 5%.42 These figures show that the ethical drug industry is one of the leading profit-making industries.

Justification for high profit is given by industry spokesmen who argue that high profits are necessary to attract the capital needed to maintain the industry’s high level of research. They also offer the argument that the drug industry is a high risk industry and that high risks justify high profits. We have already seen that research accounts for a much lower percentage of costs than does advertising, and rather than being a burden shouldered for the benefit of society, is greatly responsible for the profits in the drug industry. Mr. George S. Squibb, formerly vice-president of Squibb, states that profits, now 20% of research, could be 12% without forcing out smaller competitors or decreasing the research done by the industry.43

That there is high risk in the drug industry can be disputed in many ways. The high rate of obsolescence of drugs can be said to mean high risks, yet in very few cases have research costs not been recouped before a drug has been made obsolete. The same holds true for the risk of a developed drug being proved either ineffective or unsafe and being taken off the market, or not having its new drug application approved. High advertising often allows a company to recoup its costs before the drug is taken off the market, or as in the case of Mer-29, the side effects are not stated or proved till later. The high variation for profits between all drug firms is not satisfactory proof of high risk for in a high risk industry, some profits might be very high, but others must be very low (the whole idea of high risk), and the average would not be so high. Drs. Fisher and Hull of the Rand Corporation showed that between 1959-1964, drug industries had average profits of $18.32 of investment, and attributed only 1.68% to risk, the risk premium.44 Also, it seems obvious that an investor, when faced with an option of investing in an industry with intra-industry profits varying from 10-20%, although the variation is much higher, will invest. Thus, the drug industry has very little effort in getting capital, and its risks seem minimal.

The Food and Drug Administration has caused further deterioration to an already sick situation, by making the public believe that the drug industry is heavily and scientifically regulated. Yet the most unanimous criticism of the FDA has to be its unscientific and unsystematic methods. Even Barron’s, the voice of the corporate interest, gives testimony to that; although it is interesting that they never complained when the unscientific “witch doctors” at the FDA were acting in the best interests of the industry, when the industry was virtually self-regulated and self- inspected. The FDA has never defined an “expert” qualified to test within the industry, and it is little wonder, for the FDA seems to have its testing results determined beforehand. Political pressure rather than scientific evidence is basically the rule. As an example, with the advent of Ralph Nader and consumerism, the FDA, in one great showing of public responsibility and based on experiments with 12 rats, banned “forthwith” the use of cyclamates in the production of foods and beverages. Make no mistake, un-scientism has generally been the tool to allow the drug industry’s exploitation of the public, to give it a stamp of approval. It is a common occurence for the FDA to approve New Drug Applications, such as the recent one for L-Dopa, in an extremely short time (to allow the firm to immediately recoup its investment, or profit from it) with the assumption that more testing will be done.45 Apparently, the FDA accepts the Hussey-Stetler Test of Time, which drugs spokesmen state to be the best test for safety and efficacy of drugs,46 but which relegates the public to the role of guinea pig.

The government and the Department of Justice have not only allowed the corporate interests to maintain their degree of market control, but have been agreeable to their augmenting this control. In a speech in Atlanta on June 6, 1969, Attorney General Mitchell said, “The Department of Justice may very well oppose any merger among the top 200 manufacturing firms or firms of comparable size in other industries… the Department will probably oppose any merger by one of the top 200 manufacturing firms of any producer in any concentrated industry.” 47 Yet, of course, the Justice Department has not followed through on this statement. There have been three very recent mergers of large drug firms, which will either further concentrate the industry or give certain leading ethical drug companies more capital with which to exploit the smaller firms and the public. Merck and National Starch and Chemical merged and the expectation is that 5 cents a share will be added to Merck’s annual earnings48 In a merger approved December 11, 1970, Schering (ethical)-Plough(proprietary merged, where the total value of the company will now be about 1.5 billion dollars. 49 The merger of two major pharmaceutical companies, Warner Lambert Co. and Parke-Davis and Co. was allowed to go through over the objection of the Departments Anti-trust Chief Richard W. Mclaren. Warner Lambert has been a major client of both President Nixon and Attorney General Mitchell’s law firm.50

The ethical drug industry with the support of the FDA and the health establishment has proven its inability to provide basic drug and health care. The drive for profits of this capitalist industry must come ahead of how it serves the consumers of drugs. The profit motivation of the drug industry has led to the production of vast amounts of useless and dangerous new drugs; as well as to the marketing of drugs at prices discriminatory to the poor.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bauer, Raymond A., and Field, Mark G., “Ironic Clash”: US and USSR Drug Industries. Harvard Business Review, Sept.-Oct. 1962.

Bearned, Edmund P., Business Policy, Text and Cases, Richard Irwin, Inc., 1969.

Bleiberg, Robert M., “Spreading Infection,” Barron’s, Feb. 7, 1972.

Cacciapaglia, F. Jr., and Rockmand, A.B., “The Proposed Drug Industry Anti-trust Act-Patents, Pricing and the Public”, The George Washington Law Review, Vol. 30, June 1962, p. 890.

Comanor, W.S., “Research and Competitive Product Differentiation in the Pharmaceutical Industry in the US”, Economica, Vol. 31, Nov. 1964, p. 372-384.

Comanor, W.S., “Research and Technical Change in the Pharmaceutical Industry”; Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 47, May 1965, p. 182-190.

Competitive Problems in the Drug Industry, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Monopoly of the Select Committee in Small Business, US Senate, on Present Status of Competition in the Drug Industry, Parts 1 &5, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1968.

Cooper, Michael, Prices and Profits in the Pharmaceutical Industry, Pergamon Press, 1967.

Davies, Wynd lam, The Pharmaceutical Industry, Pergamon Press, 1967.

Drug Industry Anti-trust Act, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Anti-trust and Monopoly, 87th Congress, Session 1, 1961, Part 1,4, p. 2119.

Handler, Milton, Trade Regulation- 1970 Supplement, Edition 4, Foundation Press, Mineola, NY, 1970, p. 56-106.

Harris, Richard, “Annals of Legislation, the Real Voice,” The New Yorker, March 14, 21, 28, 1964.

Kaysen, Carl and Turner, Donald, Anti-trust Policy, Harvard U. Press, 1965.

Hearings on Administered Prices before the Subcommittee on Monopoly of the Select Committee on Small Business, Senate Committee of the Judiciary, 86th Congress, Session 1, part 18.

Mintz, Morton, The Therapeutic Nightmare, Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston, 1965.

Model, Dr. Walter, Time Magazine, May 26, 1961, p. 73.

New York Times, Oct. 23, 1970, p. 45, Nov. 24, 1970, p. 24, Nov. 26, 1970, p. 1, Dec. 11, 1970, p. C-73, Dec. 21, 1970, p. C-20, Dec. 30, 1970, p. C-33.

Prescription Drug Industry-Fact Book, Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Assn., 1970.

Silberman, Charles, Fortune, May, 1960, p. 139, 275-277.

Study of Drug Purchase Problems and Policies, US Dept. of HEW, US Govt. Printing Office, 1966.

Turner, Donald, “Scope of Anti-trust and Other Economic Regulatory Policies”, 82s Harvard Law Review, 1207, (169).

Value Line Investment Survey, Vol. 4, Feb. 12, 1965, p. 426, Edition 4, Aug. 7, 1970, p. 460-578.

Walker, Hugh, “Price Levels and Market Power in the Ethical Drug Industry”, Econometrica, Vol. 36, No. 5, p. 446.

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 4 <<

FOOTNOTES

- Morton Mintz, The Therapeutic Nightmare, p. 55

- Richard Harris, “Annals of Legislation, the Real Voice,” p. 63

- Prescription Drug Industry Fact Book

- NY Times, Dec. 30, 1970, p. 33-C

- Milton Handler, Trade Regulation

- Drug Industry Anti-trust Act, Pt. 4, p. 2119

- ibid, Pt. 1, p. 68-69

- Charles Silberman, Fortune, May, 1960

- W.S. Comanor, Economica, Vol. 31, Nov. 1964

- op. cit, Silberman

- Pt. 1., p. 383

- F. Cacciapaglia, Jr., “The Proposed Drug Industry Anti-trust Act-Patents, Pricing and the Public”

- op. cit, Comanor

- op. cit, Silberman, p. 138

- op.cit,Mintz,p.165

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 5, p. 2065

- ibid, Pt. 1, p. 2113-2120

- ibid

- op. cit, Mintz, p. 560

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, p. 2118

- ibid

- W.S. Comanor, “Research and Technical Change in the Pharmaceutical Industry”, Review of Economics and Statistics.

- Raymond A. Bauer and Mark G. Field, “Ironic Clash”, p. 168

- ibid

- Walter Model, Time, p. 73

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 1, p. 375

- op. cit, Mintz, p. 232

- Hugh Walker, “Price Levels and Market Power in the Ethical Drug Industry”

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 5, p. 2044

- op. cit, Cacciapaglia

- op. cit, Mintz, p. 493

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 1 ., p. 1918

- ibid, p. 354

- op. cit, Mintz, p. 306

- ibid, p. 60

- ibid, p. 59

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 5, p. 1691

- ibid, p. 1735

- ibid, p. 1908

- Value Line Investment, Aug. 7, 1970, p. 509

- op. cit, Drug Industry Fact Book, p. 24

- op. cit, Competitive Problems, Pt. 5, p. 1820

- ibid, p. 1605

- ibid, p. 820

- op. cit, Value Line Investment

- op. cit, Mintz, p. 94

- op. cit, Milton Handler, p. 71

- op. cit, Value Line Investment, p. 536-637

- NY Times, Dec. 11, 1970, p. 73-C

- ibid, Nov. 26, 1970, p. 1