This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Bottle Babies and Managed Mothers

by Mark Wilson

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 13, No. 1, January/February 1981, p. 17 — 24

Mark Wilson works with a group of people on a wide range of scientific and political-economic problems in food production. nutrition, population and health. You are encouraged to contact them at the Center for Applied Science. Room 1/04, 665 Huntington Ave ., Boston. MA 02115. He is also a member of the New World Agriculture Group (NWAG).

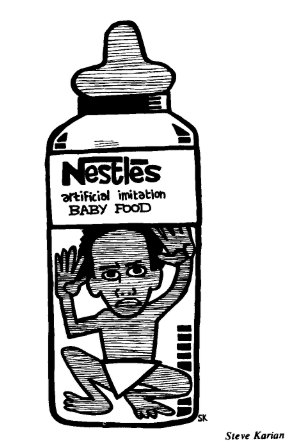

Opposition to the aggressive marketing of infant formula by multinational corporations has gained widespread recognition and support over the last few years. Numerous humanitarian groups with widely varying political perspectives have joined in condemning the widespread and misleading advertising, ready availability, improper labeling, free samples, and direct sales of artificial infant foods. While being told that infant formula will improve the well being of both infants and mothers, its use, particularly in the Third World, is actually resulting in millions of infant deaths.

Thus far, the movement against infant formula has mostly focused rather narrowly on the health or promotional aspects of what has come to be known as the great “bottle baby” scandal. This growing movement has already generated considerable literature on the marketing, nutritional, disease, and micro-economic issues. In addition, there are many epidemiological and physiological studies that clearly show the superiority of breast feeding over infant formula (see box). However, the biological evidence, which is abundant and consistent, cannot be fully understood nor acted upon until it is put into a macro-political context. The focus of study must now turn to the underlying determinants of who eats how much of what: the productive and social relations of the ownership and control of science and technology, and the ideology that interacts with these relations. This essay is an attempt to outline some of the issues with particular regard to the bottle baby problem.

Immediate Causes of the “Bottle Baby” Problem

The debate surrounding the “bottle baby” problem has focused primarily on the promotional tactics in the Third World by multinational corporations of developed capitalist countries. There is no doubt that massive media advertising, free samples, and advice from physicians and nurses (and company sales people who appear as such) have led many Third World mothers, who are quite capable of breast feeding their children, nevertheless to buy and use formula.(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7,8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17) The high cost of formula that women are encouraged to buy leads to increased poverty. Over-dilution of the formula often causes infant malnutrition and/or death. It is in this sense that multinationals kill babies. However, by limiting our analysis to this more immediate level, we may be only tackling the immediate symptoms and not the underlying causes.

For example, if the “problem” is viewed as unethical promotion and ignorance, the solution must be regulation and education. Infant formula producers have to be asked, or forced to behave, more “ethically”. In response, the corporations then argue that they are merely making available a product that mothers already want, that preparation and use instructions are clearly printed on the container, and that we must maintain a system of “freedom” and “democracy” to allow people to make choices and profits.

Secondly, since mothers are ignorant, national governments and health workers must be taught, and then pass on to the mothers, the value of breast feeding and the dangers of bottle feeding. (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24) As a result mothers will know how to interpret, and more effectively shield themselves from, the company’s sales efforts.

Undoubtedly, these tactics have been somewhat effective; indeed, I support them as necessary immediate measures that appear to have improved the well being and survival of some infants. But however necessary this approach might be, it is not enough; it is acting on the symptoms but not the underlying causes. This reform approach to the bottle baby problem does not seriously challenge the set of social relations of power, or of the underlying and reinforcing ideology that ultimately create the conditions in which the problem exists and of which it is a part. By analyzing the problem within the confines of the existing system of social-political-economic relations, the criticisms that are mounted can only propose defensive, rear guard, reform. Only after there are millions of unnecessary infant deaths, and Third World countries deepen their dependence on the developed countries, is it possible to limit or redirect the marketing. But in addition, the “problem” can come to be seen as infant formula, not malnutrition and disease; as misleading advertising and not the oppression of women; as the high cost of formula and not the exploitation and oppression of the Third World. (25,26)

In part, I am raising a procedural issue of tactics and strategy. Most critics have largely ignored the strategic problems that involve a structural analysis and have focused on immediate action.

In part, I am raising the issue of the “levels” of analysis and of causation: proximate-distant, immediate-ultimate. Malnutrition is, at the molecular level, a problem of the amount and types of biochemical reactions. This is determined in part by behavior at another level: that of the whole organism. But with people, our individual behavior is largely affected by even “higher” levels, that of social groups. Our system of social relations and consciousness create both the possibilities and the constraints within which the biochemical reactions take place.

Further, I am criticizing the reductionism in analyses that separates levels, even parts of levels and emphasizes lower levels as more “basic”, thus more important to our understanding. We end up knowing much about biochemical, much less about the political-economic aspects, and have virtually no understanding of how these and other aspects interrelate.

In what follows, I outline some of these productive and social relations as something subject to change rather than an accepted “given” of the bottle baby problem; these are some of the issues that must be addressed if significant changes are to be made.

Patriarchal and Capitalist Science and Technology

Among the most profound forces shaping the existence of most humans in the world today are the domination and exploitation of women by men, and of one class or nation by another. Patriarchy, capitalism and imperialism are complex, partly overlapping systems of social, productive, reproductive, and ideological relations that structure our beliefs and interactions with each other and with nature. An understanding of the “bottle baby” problem is incomplete without analysis at this level. However, it is as useless to simply assert this without further explanation, as it is impossible to attempt any detailed analysis here. Thus, I have outlined very generally some of the ideological, productive and social relations that are involved. My claim is that changing these social relations is ultimately necessary, but not sufficient, to eliminate the kinds of health/social problems of which the “bottle baby” syndrome is but one.

To understand why and how infant formula is currently produced and marketed, it is useful to consider how commodities in general are conceived and used, and the role of science and technology in that process. Most contemporary science and technology can be broadly viewed in terms of three characteristics: commodity production, reductionism/mechanism and objectivity.

First, capitalist science and technology, directed and controlled by the capitalist class, is used for the production of commodities. Whether or not what is produced is “needed”, “healthy”, “practical”, or in any sense improves human well being is secondary to the concern that it be profitable and marketable. Thus science and technology are used to produce and promote commodities that maintain the dominance of the capitalist class. (27, 28, 29, 30, 31) In one sense, infant formula is yet another of many commodities developed by science to increase the profits and power of the few who direct it.

Second, contemporary capitalist science, including medicine, is increasingly reductionist and mechanistic in its posing and solving of problems. The infant’s overall physical, psychic and social well being can thus be reduced to a series of smaller isolated problems of which nutrition is but one. Nutrients are nutrients and the constellation of other interrelated factors is someone else’s department. The conceptualization of all these processes as isolable is essentially mechanistic: much like a machine, the body (more recently the mind as well) is seen as a living machine operating according to mechanical/physical principles. Even though most parts are needed for the machine to function well, separate parts can be removed, improved and replaced. Infant formula is thus a fuel that can be seen as a replacement analogue of the fuel that has been isolated from the much more complex social and biological process of breastfeeding.

Third, the development of scientific objectivity and the attempt to separate feeling from thinking (actually the denial of feeling) has led to scientistic objectification. Characteristic of most men (men being the dominant force in the development of science), objectification is particularly pronounced in the technology for and medical science administered to women. (32, 33) Women, infants, and breast milk all become objects to be treated, manipulated, duplicated, and operated. Referring to all women, Arditti has written that “scientists have studied us as the reproductive systems of the species, and we have been reduced to our reproductive organs, our secondary sexual characteristics and/or sexual behavior.” (34)

Little of this process, though assuredly some, is conscious action on the part of (male) scientists and capitalists. The sexism, elitism and objectification are part of an ideological and social system which structures thought and relations and allows many to see it as natural, inevitable and immutable. Yet, it is undeniable that men in general, and particularly those of the capitalist class, derive continued benefits of power and wealth from the system that they control.

These processes allow for infant feeding, like any other labor in the factory, field or home, to be organized and directed by science. The process of scientific management (35) has been extended to other activities of motherhood and has created the industrial model of baby feeding. (36) The three characteristics of science and technology: development toward commodity production, reductionism and mechanization, and objectification of people, can be seen as characteristic of medicine as well.

Medical Science, Women, and Babies

A male dominated medical science has, especially within this century, taken away much of the health care and healing power that was traditionally women’s activity. (37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44) Birthing in particular, and reproduction in general, have become a male controlled medical event. Accompanying this is the creation of specialized knowledge that forces women to become increasingly dependent upon (mostly male) physicians for advice. This is one of the major pathways by which women are encouraged to use artificial formula that they rarely need.

Infant formula as a commodity is promoted as essential food, but also as a non-prescription drug. This is, in part, a result of the investment and marketing history of the corporations that sell infant formula: agribusiness and pharmaceuticals. But the market had to be created and developed from its beginnings in the late 19th century.(45)

The tremendous success of the effort at marketing infant formula, as both food and as a “medicine”, is based on the power of “expertise” in the medical profession and the power of advertisement, both of which play on people’s fears and aspirations. This ideological power interacts with a real material inequality that includes lack of access to knowledge by women in general and poor women in particular. This has increasingly become a source of social control.

The medical system has not only expanded the number of kinds of matters it addresses, but also its jurisdictions.(46) Through both processes this cooptation leads to increasing control. The medical system is replacing lay sources of help. Decisions about and knowledge of infant feeding which, in most cultures, have traditionally been those of the mother and a supportive network of other women (relatives and friends) (e.g. 47, 48, 49, 50, 51), are now the domain of science, medicine. and technology.

The relationship that birthing women have with the medical establishment is increasingly one of submission to authority.(52) (This has been the case for decades in developed countries and is increasingly the case in the Third World.) Established in clinics and hospitals, this dependence of mothers on medical “authority” is fostered during the hospital birth period, extends to most people wearing “whites” and is brought into the home where advertising bombardments reinforce what the “authorities” have said. Thus, the approach to, and effectiveness of, formula promotion has its roots in a deeper system of power relations between men and women, science and women’s knowledge, the “expert” physician and the patient.

BREAST VS. BOTTLE CONTROVERSYResults of health and nutritional studies. Epidemiological studies consistently show that, under the living conditions of most people in the world today, artificially-fed infants have much higher rates of mortality and morbidity (disease and malnutrition) than breast-fed infants (see Wray’s recent review.*(53)) Studies in the U.S. and Europe show a pattern changing with time: before the mid-1930’s all major studies showed significantly lower incidence of death and disease among breast-fed babies, while after the thirties the few studies done on relatively wealthy, well-educated people with access to health care facilities showed no significant differences in morbidity or mortality between artificially-fed and breast-fed infants. (Many other studies did show significant differences in morbidity.) This pattern is not repeated in the Third World: results consistently show significantly higher mortality and morbidity rates in infants fed an artificial formula diet. Other studies have shown that breast-fed babies have less childhood tooth decay.(54,55,56,57,58) Socio-physiologic factors in the controversy. There is a multitude of studies showing the beneficial effects of breast milk and breast-feeding.(see 59,60,61,62,63,64,65 for reviews) The antibiotic properties of human colostrum and breast milk are now well known. (see reviews in 66,67,68,69,70,71,72) Immunoglobulins and phage cells transmitted to breast-fed infants increase resistance to pathogens. These elements are absent from artificial infant foods. Infant formulas can closely replicate the known nutrient content of human milk (73,74), yet it is well documented that the nutrients that many infants actually receive from artificial feeding are grossly insufficient (75, 76) or excessive.(77,78) Problems of under- or over-dilution of the artificial formula, and also the introduction of pathogens ( 79 ,80), are not present with breast-feeding. Most studies (81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88), especially those involving poor people, estimate greater per-family and national costs from bottle feeding of infants. Further savings would be expected from breast-feeding when the improved health and lowered health care expenditures are considered. One to three percent of mothers fail to produce an adequate amount of milk due to organic, or natural, problems. Most mothers who fail to produce milk do so because they are fearful or not knowledgeable, psychological factors directly traceable to sociological conditions created by the use of infant formula (see the accompanying article), and to the promotional tactics used in its marketing. (see 89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98) Legitimate uses of artificial milk. Artificial feeding may be useful or essential in circumstances involving “inborn errors of metabolism” (99,100,101), illness of the infant (102), or illness or death of the mother. In some cases where pollutants contaminate breast milk or where the mother must receive drugs, artificial foods are necessary. (103,104,105) Lactation failure or inadequacy may also be compensated for with infant formula feeding. but these very problems would be reduced to 1-3% of mothers were it not for the prevalence of infant formula, as mentioned above. In cases of extreme malnutrition mothers may be unable to produce the quality or quantity of milk for optimal infant nutrition. (see 106,107,108 for reviews) Use of formula feeding may be an appropriate palliative measure, but the high cost of the formula would more usually exacerbate the poverty and associated malnutrition. Ultimately, the problem is not physiological. but social, and it is at this level that solutions must be sought. We are now faced with the problem of why infant formula is produced, marketed, purchased, and used in such quantity. It would appear that at the heart of the problem is the basic structure and ideology of the capitalist/patriarchal system, as shown in the accompanying article. *Numbers refer to references listed at the end of Wilson’s article. |

Advertising and Ideology

An important component of the system just outlined is the process by which people, in particular women, come to accept these power relations. Advertising functions as an ideological force which supports and partly creates such relations.

As a political-economic system which thrives on consumption by most and accumulation by a few, capitalism, neo-colonialism and imperialism consistently require aggressive promotion. Advertising “works” in that it creates a “need” for some product or increases the frequency of sales of a commodity that is already being bought. (109, 110, 111) As one New York investment banker frankly feared: “Were advertising not so important… food would be bought on the basis of economy and nutritional value.” (112) More and more with the development of monopoly capitalism, price competition has decreased as a means of attracting purchases. Advertising that focuses on variation in appearance, packaging, and reputed qualities increasingly determines what we buy. (113) The apparent superiority of one product over another is sufficient to establish its dominance. In this case, we see the establishment of the apparent superiority of bottle formula over breast milk even though the formula costs much more. Ironically: the users of this expensive formula, expensive mostly because of advertising costs and not the cost of production, are paying dearly for the very advertising that is coercing them to buy it! Baran and Sweezy summarize the problem nicely:

The function of advertising, perhaps its dominant function today, thus becomes that of waging, on behalf of the producers and sellers of consumer goods a relentless war against saving and in favor of consumption. And the principle means of carrying out this task are to induce changes in fashion, create new wants, set new standards of status, enforce new norms of propriety. The unquestioned success of advertising in achieving these aims has greatly strengthened its role as a force counteracting monopoly capitalism’s tendency to stagnation and at the same time marked it as a chief architect of the famous “ American Way of Life”. (114, p.128)

Anti-Science Victim Blaming

“Structural” constraints such as these just outlined have for the most part not been questioned by infant formula critics. There are exceptions, such as Jelliffe and Jelliffe who do criticize the “commercialization” of formula and the “iatrogenic”*[*iatrogenesis is the process of the creation of illness in patients by the actions of medical personnel. (see 115) ] nature of bottle fed malnutrition. (116, 117, 118, 119) However, the danger that this approach engenders is that it can become simplistically anti-scientific and anti-technological. For example, Jelliffe attributes the problem in the decline of breast feeding to “linear-Westernism” and the “dramatic scientific discoveries and ways of thought which occurred with the industrial revolution and with the parallel medical evolution of the last century”. (120 p. 233) Without identifying the social forces that lie behind the thought and applications, we can only conclude that science and technology per se are at fault. Similarly, the “iatrogenic” effect of the physician’s advice, operating here via the advocacy of infant formula, can be used as an argument against physicians and even against knowledge.

The science/technology problem is not “whether”, but “which” and “for whom”. No doubt some technologies and sciences are inherently undesirable from an anti-sexist, anti-racist and anti-capitalist point of view. But this must not become an argument against all science. Science can be used to benefit oppressed peoples though generally only when it is under their control.

Most studies of the “social” issues concerning the rapid increase in infant formula use are in one sense descriptions rather than analyses: “urbanization,” increase in “working mothers,” “lack of education,” “modernization”, etc. This makes it easy to blame the victim for the unfortunate choices she has made. While it is clear that advertising and other promotion has “pulled” women into the infant formula syndrome, they are not simply helpless pawns. There are real forces that show seemingly irrational choices to be tactically rational choices in an irrationally constrained and oppressive situation.

For example, bottle feeding represents the only real alternative (albeit more risky and costly) to many women who work and hence cannot breast feed. At-the-job, paid nursing time and child care facilities are not going to be willingly offered by a capitalist whose priority is minimizing costs (primarily labor costs) while maximizing the amount of commodity produced. (The proliferation of child care facilities during World War II, which were removed at the end of the war, is a special case that actually supports this claim.) Unlike China, where paid post-partum leaves, creches, and nursing breaks allow women to maintain their jobs and income, and still breast feed (121), women working as wage laborers in most of the capitalist world have no such opportunities.

While formula makes the sharing of infant feeding possible, in practice, of course, it is typically the mother (or aunt or grandmother) who prepares and administers the bottle, and cleans up after. At a time when more childcare technology is being developed, mothers are actually spending more time at it. (122) It is not surprising that, especially in sexist societies, Third World and developed, where cleaning, childcare, cooking, etc. (and often wage labor as well) are women’s work, women will want at least to allow the possibility that someone else might help with infant feeding.

Although some have argued that the roots and continued existence of sexist divisions of labor and power lie in women’s biology (123), I argue that sexism is a social disease for which there is no technological fix (least of all, one coming from a male dominated technology!). Indeed, it is the pattern of most technological development and commodity production under capitalism that it further oppresses and alienates the people who use it. (124) The interjection of commodities into social relations and the increasing dependence on commodity acquisition and consumption in developing a sense of well being lie at the heart of this process. Infant formula is an example, but it also has direct material roots. Artificial feeding was originally pushed in the U.S. beginning in the late 1800’s (see 125) not only because its sale made profits but perhaps also because its use permitted the inclusion of reproductive-age women into the wage labor force (thus only compromising slightly their unpaid labor in the home).

There is however the danger of a reactionary backlash in which demands for the elimination of oppressive and exploitative sexual division of labor, in the family and at the factory (that must accompany a non-exploitative increase in breastfeeding) are dropped and breast feeding is seen as simply a motherly duty. Breastfeeding is neither magically easy nor simply part of a larger set of “womanly” activities (126) that keep mothers at home tending to their “natural” functions.

It is true that breastfeeding is one of the jobs that only women can perform. It is, however, also one of many activities that are socially prescribed by a system of male dominance. The liberation of women is a problem of changing society, not eliminating biology. What Arditti writes regarding pregnancy is equally valid when applied to infant feeding:

…it is paradoxical that the excesses of an impersonal technology developed by males in a sexist society can be viewed as important for the liberation of women… Technology will not erase 50,000 years of female oppression. (127, p. 31)

A feminist or anti-capitalist analysis must not view technological developments as necessarily liberating: oppression and exploitation are not determined by our biology or by “nature”, but are created by people in particular kinds of social formations and relations.

Conclusion

The type of analysis just outlined, if used to develop a course of action, might not appear very promising. A major reorganization of social relations and ideology is not likely to be won within the next month or two, and in the meantime, malnutrition and disease in the Third World is claiming thousands of infants daily. But such an analysis, when more fully developed, is not intended for short term reform. Rather, I think it serves other purposes.

First, by critically questioning the deeper roots of malnutrition, we are better able to understand relationships among levels of causation and across “disciplines”; this allows for a more comprehensive attack on the problem and can induce others to work for social change where heretofore, the problem may have been seen simply as one of technology or ignorance. This is not an issue to be addressed only by specialists in infant nutrition. Furthermore, it may serve to unite and make more effective people who are struggling over particular issues that have the same underlying causes.

Secondly, we become better able to oppose the tendency (resulting from our training) to examine problems as isolable units to be solved one at a time. The relationship of the particular infant feeding problem to those of poverty in general, poor sanitation, inadequate housing, insufficient education, sexism, and elitism can be understood as part of the general problem of development in the Third World. Thus, we can begin to see the possibilities of working to change a few of the more pervasive social/ecological relations that underlie many particular manifestations.

Third, the integration of short term and long term efforts becomes an issue. It becomes possible to ask not only what tactics might be developed to immediately oppose the oppressive conditions, but how these tactics fit into a long term strategy for social change that will eliminate many problems (though create new ones) and minimize the need for short term responses. It raises the possibility of the realistic planning for health and not simply the fight against ill-health. Only then can the use of infant formula become part of a preventative system of well being instead of the immediate cause of disease and death.

>> Back to Vol. 13, No. 1 <<

REFERENCES

- Anderson, S.A., H.I. Fisher and K.D. Fisher, 1980. A background paper on infant formula. Mimeo, 44 pgs. Bureau of Foods, FDA, HEW.

- Berg, A., 1973. The Nutrition Factor. Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C., 290 pgs.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1977. Human Milk in the Modern World. Oxford University Press, London.

- Latham, M.C., 1977. Infant feeding in national and international perspective: An examination of the decline in human lactation and the modern crisis in infant and young child feeding practices. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 300:197-209.

- Popkin, B.M. and M.C. Latham, 1973. The limitations and dangers of commerciogenic nutritious foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 26:1015-23.

- Jelliffe, D.B., 1972. Commerciogenic malnutrition. Nutr. Rev. 30(9): 199-205.

- Astrachan, A., 1976. Milking the Third World. The Progressive 40:34-7.

- Bader, M., 1976. Breast-feeding: the role of multinational corporations in Latin America. Intern. J. Health Serv. 6(4):609-26.

- Dwyer, J., 1975. The demise of breastfeeding: Sales, sloth or society?, pp. 331-72. In Priorities in Child Nutrition, Vol. II., J. Mayer, ed. Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston.

- Greiner, T., 1975. The promotion of bottle feeding by multinational corporations: How advertising and the health professions have contributed. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No.2.

- Jelliffe, E.F.P., 1977. Infant feeding practices: Associated iatrogenic and commerciogenic disease. Pediat. Clin. of N. Am. 24(1) 49-61.

- Lappe, F.M. and E. McCallie, 1978. On the bottle from birth. Food Monitor, Sept./Oct. 1978:13-14.

- Margulies, L., 1977. A critical essay on the role of promotion in bottle feeding. Population Advisory Group of the U.N. Bulletin 7(3-4):73-83.

- Muller, M., 1975. The Baby Killer (2nd ed.). War on Want, London, 23 pps.

- Raphael, D., 1973. The role of breastfeeding in a bottle-oriented world. Ecol. Food & Nutr. 2:121-6.

- Raphael, D., 1977. Mothers in poverty: Breast feeding and the maternal struggle for infant survival. Lactation Review 2(3).

- WHO/UNICEF, 1979. Statement on infant and young child feeding. Meeting on infant and young child feeding. FHE/ICF/REP/6/Rev. 2.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, 1978. Breast-feeding. Ped. 62(4):591-601.

- Greiner, T., 1975. The promotion of bottle feeding by multinational corporations: How advertising and the health professions have contributed. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No.2.

- Latham, M.C., 1977. Infant feeding in national and international perspective: An examination of the decline in human lactation and the modern crisis in infant and young child feeding practices. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 300:197-209.

- Dwyer, J., 1975. The demise of breastfeeding: Sales, sloth or society?, pp. 331-72. In Priorities in Child Nutrition, Vol. II., J. Mayer, ed. Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston.

- Helsing, E., 1976. Lactation education: The learning of the “obvious.” In Breastfeeding and the Mother, pp. 215-30. CIBA Found. Symp., Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1973. Education of the public for successful lactation. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2:127-32.

- Jones, R.A.K. and E.M. Belsay, 1978. Common mistakes in infant feeding. Br. Med. J. 2:112-5.

- Barnet, R.J. and R.E. Muller, 1974. Global Reach. Simon & Schuster, New York.

- Solimano, G. and J. Sherman, 1979. Public health considerations in human lactation, pp. 149-54. In Breast Feeding and Food Policy in a Hungry World. D. Raphael, ed. Academic Press, New York.

- Baran, P.A. and P.M. Sweezy, 1966. Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 401 pgs.

- Braverman, H., 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 465 pgs.

- Dickson, D., 1974. Technology and the construction of social reality. Radical Science Journal 1:29-50.

- Ehrenreich, B. and J. Ehrenreich, 1978. Medicine and social control, pp. 39-79. In The Cultural Crisis of Modern Medicine, J. Ehrenreich, ed. Monthly Review Press, New York.

- Sohn-Rethel, A., 1975. Science as alienated consciousness. Radical Science Journal 2/3:65-101.

- Arditti, R., 1974. Women as objects. Science and sexual politics. Science for the People VI(5):8.

- Ehrenreich, B. and D. English, 1979. For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women. Andron. Press, New York, 369 pgs.

- Arditti, R., 1980. Feminism and science, pp. 358-68. In Science and Liberation. R. Arditti, P. Brennan, and S. Cavrack (eds.), South End Press, Boston.

- Braverman, H., 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 465 pgs.

- Ehrenreich, B. and D. English, 1979. For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women. Andron. Press, New York, 369 pgs.

- Ehrenreich, B. and D. English, 1979. For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women. Andron. Press, New York, 369 pgs.

- Arditti, R., 1980. Feminism and science, pp. 358-68. In Science and Liberation. R. Arditti, P. Brennan, and S. Cavrack (eds.), South End Press, Boston.

- Brack, D.C., 1978. Breastfeeding: a function of women’s power in social change. Annual Meeting, Sociologists for Women in Society, San Francisco, September, 1978.

- Braverman, H., 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 465 pgs.

- Brack, D.C., 1975. Social forces, feminism and breast feeding. Nursing Outlook 23(9):556-61.

- Chodorow, N., 1979. Mothering, male dominance and capitalism, pp. 83-106. In Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, Z.R. Eisenstein, (ed.), Monthly Review Press, New York, 394 pages.

- Ehrenreich, B. and J. Ehrenreich, 1978. Medicine and social control, pp. 39-79. In The Cultural Crisis of Modern Medicine, J. Ehrenreich, ed. Monthly Review Press, New York.

- Helsing, E., 1976. Lactation education: The learning of the “obvious.” In Breastfeeding and the Mother, pp. 215-30. CIBA Found. Symp., Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Apple, R., 1978. What’s a mother to do? The commercialization of artificial infant feeding, 1880-1940. Mimeo, 4th Berkshire Conference, Mt. Holyoke, Ma.

- Ehrenreich, B. and J. Ehrenreich, 1978. Medicine and social control, pp. 39-79. In The Cultural Crisis of Modern Medicine, J. Ehrenreich, ed. Monthly Review Press, New York.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1975. Human Milk, nutrition, and the world resource crisis. Sci. 188:557-61.

- Muller, M., 1975. The Baby Killer (2nd ed.). War on Want, London, 23 pps.

- Raphael, D., 1973. The role of breastfeeding in a bottle-oriented world. Ecol. Food & Nutr. 2:121-6.

- Helsing, E., 1976. Lactation education: The learning of the “obvious.” In Breastfeeding and the Mother, pp. 215-30. CIBA Found. Symp., Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Arditti, R., 1980. Feminism and science, pp. 358-68. In Science and Liberation. R. Arditti, P. Brennan, and S. Cavrack (eds.), South End Press, Boston.

- Ehrenreich, B. and D. English, 1979. For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women. Andron. Press, New York, 369 pgs.

- Wray, J.D., 1980. Feeding and survival: Historical and contemporary studies of-infant morbidity and mortality. In Yearbook of International Maternal and Child Health, D.B Jellife and E.F.P. Jelliffe, eds. Oxford University Press (In Press).

- Oats, R.K., 1973. Infant feeding practices. Br. Med. J. 2:762-4.

- Richardson, B.D. and P.E. Cleaton-Jones, 1977. Rampant caries and labile caries—Symposium. S. Afr. Med. J. 51:527.

- Shelton, P.B., et. al., 1977. Nursing bottle caries. Ped. 59:77.

- Almroth, S. and T. Greiner, 1979. The economic value of breast feeding. FAO Food & Nutrition Paper 11, 89 pgs.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition, 1976a. Special diets for infants with inborn errors of metabolism. Ped. 57:783.

- Addy, D.P., 1976. Infant feeding: a current view. Brit. Med. J. 1:1268-71.

- Aitken, F.C. and F.E. Hytten, 1960. Infant feeding: Comparison of breast feeding and artificial feeding. Nutr. Abs. Review 30:341-73.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, 1978. Breast-feeding. Ped. 62(4):591-601.

- Anderson, S.A., H.I. Fisher and K.D. Fisher, 1980. A background paper on infant formula. Mimeo, 44 pgs. Bureau of Foods, FDA, HEW.

- Berg, A., 1973. The Nutrition Factor. Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C., 290 pgs.

- Dickman, S.R., 1979. Breastfeeding and infant nutrition. J. Fam. Comm. Hlth. 1:19-29.

- Ebrahim, G.J., 1978. Breast-feeding: The Biological Option. MacMillan, London.

- Chandra, R.K., 1978. Immunological aspects of human milk. Nutr. Rev. 36:265-72.

- Goldman, S.A. and W.C. Smith, 1977. Host resistance factors in breast milk. J. Ped. 82:1082.

- Hanson, L.A., B. Carlsson, S. Ahlsted, et. al., 1975. Immune defense factors in human milk, milk and lactation. Mod. Prob. Pediat. 15:63.

- Mata, L., 1978. Breast feeding: Main promoter of infant health. Am.J. Clin. Nutr. 31:2058-65.

- Pittard, W.B., 1979. Breast milk immunology—a frontier in infant nutrition. Am. J. Dis. Child. 133:83-7.

- Welsh, J.K., and J.T. May, 1979. Anti-infective properties of breast milk. J. Ped. 94(1):1-9.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition, 1976b. Commentary on breast feeding and infant formula, including proposed standards for formula. Ped. 51:278-85.

- Hambreas, L., 1977. Properitary milk versus human breast milk in infant feeding: A critical appraisal from the nutritional point of view. Ped. Clinics. of N. Am. 24:17-35.

- Berg, A., 1973. The Nutrition Factor. Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C., 290 pgs.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1977. Human Milk in the Modern World. Oxford University Press, London.

- Oats, R.K., 1973. Infant feeding practices. Br. Med. J. 2:762-4.

- Hall, D.B.M., et. al., 1976. Artificial feeding of Black infants. S. Afr. Med. J. 50:761-63.

- Berg, A., 1973. The Nutrition Factor. Brookings Institute, Washington, D.C., 290 pgs.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1977. Human Milk in the Modern World. Oxford University Press, London.

- Almroth, S. and T. Greiner, 1979. The economic value of breast feeding. FAO Food & Nutrition Paper 11, 89 pgs.

- Greiner, T., 1977. Regulation and education: strategies for solving the bottle feeding problem. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No. 4, 78 pgs.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1975. Human Milk, nutrition, and the world resource crisis. Sci. 188:557-61.

- Latham, M.C., 1977. Infant feeding in national and international perspective: An examination of the decline in human lactation and the modern crisis in infant and young child feeding practices. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 300:197-209.

- Latham, M.C., 1979. International perspectives on weaning foods: The economic and other implications of bottle feeding and the use of manufactured weaning foods, pp. 119-28. In Breastfeeding and Food Policy in a Hungry World, D. Raphael, ed. Academic Press,

New York. - McKigney, J., 1971. Economic aspects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 24:1005-12.

- Popkin, B.M. and M.C. Latham, 1973. The limitations and dangers of commerciogenic nutritious foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 26:1015-23.

- Popkin, B.M. and F.S. Solon, 1976. Income, time, the working mother and child nutrition. J. Trop. Ped. 22:156.

- Davies, D.P., 1977. Adequacy of expressed milk for early growth of preterm infant. Arch. Dis. Child. 52:296-301.

- Davies, D.P. and T.l. Evans, 1976. Failure to thrive at the breast. Lancet 2:1194-5.

- DeCastro, F.J., 1969. Decline of breast feeding. Clin. Ped. 7:703.

- Jelliffe, D.B., 1972. Commerciogenic malnutrition. Nutr. Rev. 30(9): 199-205.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1978. The volume and composition of human milk in poorly nourished communities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 31:492-515.

- Wray, J.D., 1978. Maternal nutrition, breast-feeding and infant survival, pp. 197-229. In Nutrition and Human Reproduction, W.H. Mosley, ed. Plenum Press, New York.

- Astrachan, A., 1976. Milking the Third World. The Progressive 40:34-7.

- Bader, M., 1976. Breast-feeding: the role of multinational corporations in Latin America. Intern. J. Health Serv. 6(4):609-26.

- Dwyer, J., 1975. The demise of breastfeeding: Sales, sloth or society?, pp. 331-72. In Priorities in Child Nutrition, Vol. II., J. Mayer, ed. Harvard University School of Public Health, Boston.

- Greiner, T., 1975. The promotion of bottle feeding by multinational corporations: How advertising and the health professions have contributed. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No.2.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition, 1976a. Special diets for infants with inborn errors of metabolism. Ped. 57:783.

- Borgstrom, D., A. Dahlquist and L. Hambracus, 1973. Intestinal Enzyme Deficiencies and their Nutritional Implications. Almquist and Wiksell, Uppsala, Mi.

- O’Brien, D., 1978. Specific biochemical lesions and the dietary management of inborn errors of metabolism, pp. 113-6. In Nutrition in Transition, P.L. White and N. Selvey, eds. AMA, Monroe, Wise.

- McCracken, G.H. and A. Eitzman, 1978. Necrotizing enterocolitis. Am.J. Dis. Child. 132:1167.

- Bakken, A.F. and M. Seip, 1976. Insecticides in human breast milk. Acta. Paed. Scand. 65:535.

- Olsyyna-Marzzs, A.E., 1978. Contaminants in human milk. Acta. Paed. Scand. 67:571-5.

- Benson, J.D., 1976. Lack of milk as a cause for the early cessation of breast feeding: A review of the literature. Infant Nutr. Res., December, 1972.

- Jelliffe, D.B., 1972. Commerciogenic malnutrition. Nutr. Rev. 30(9): 199-205.

- Jelliffe, D.B. and E.F.P. Jelliffe, 1978. The volume and composition of human milk in poorly nourished communities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 31:492-515.

- Wray, J.D., 1978. Maternal nutrition, breast-feeding and infant survival, pp. 197-229. In Nutrition and Human Reproduction, W.H. Mosley, ed. Plenum Press, New York.

- Baran, P.A. and P.M. Sweezy, 1966. Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 401 pgs.

- Ewen, S., 1976. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of Consumer Culture. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Popkin, B.M. and F.S. Solon, 1976. Income, time, the working mother and child nutrition. J. Trop. Ped. 22:156.

- Mazur, P., 1953. The standards we raise. Cited in Monopoly Capital, P. Baran and P. Sweezy, eds., p. 124. Monthly Review Press.

- Baran, P.A. and P.M. Sweezy, 1966. Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 401 pgs.

- Baran, P.A. and P.M. Sweezy, 1966. Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 401 pgs.

- Illich, I., 1975. Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health, Calder & Boyars, London.

- Jelliffe, D.B., 1972. Commerciogenic malnutrition. Nutr. Rev. 30(9): 199-205.

- Greiner, T., 1977. Regulation and education: strategies for solving the bottle feeding problem. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No. 4, 78 pgs.

- Jelliffe, D.B., 1976. Community and sociopolitical considerations of breast-feeding. In Breast Feeding and the Mother, pp. 231-51. CIBA Found. Symp., Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Raphael, D., 1977. Mothers in poverty: Breast feeding and the maternal struggle for infant survival. Lactation Review 2(3).

- Greiner, T., 1977. Regulation and education: strategies for solving the bottle feeding problem. Cornell U. Intern. Nutr. Monogr. Ser., No. 4, 78 pgs.

- Chung, A.W., 1979. Breastfeeding in a developing country: the People’s Republic of China, pp. 81-86. In Breastfeeding and Food Policy in a Hungry World, D. Raphael, ed. Academic, New York.

- Chodorow, N., 1979. Mothering, male dominance and capitalism, pp. 83-106. In Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, Z.R. Eisenstein, (ed.), Monthly Review Press, New York, 394 pages.

- Firestone, S., 1974. The Dialectic of Sex. Morrow, New York.

- Braverman, H., 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press, New York, 465 pgs.

- Apple, R., 1978. What’s a mother to do? The commercialization of artificial infant feeding, 1880-1940. Mimeo, 4th Berkshire Conference, Mt. Holyoke, Ma.

- Carson, M.B., ed., The Womanly Art of Breastfeeding, 2nd ed. LeLeche League.

- Arditti, R., 1974. Women as objects. Science and sexual politics. Science for the People VI(5):8.