This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Protecting Women Out of Their Jobs

by Phyllis Lehmann

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 9, No. 6, November-December 1977, p. 30–33

Okay lady, your job or your fertility, which will it be?

It sounds like a 21st Century melodrama, but for Norma James, a 34-year-old divorced mother of four, it’s all too real. James made history of sorts last year when she had herself sterilized so she could keep her job at a General Motors battery plant near Toronto.

Lead is used in automobile batteries, and if a woman inhales or swallows lead while pregnant, the metal could cause miscarriage or birth defects. GM decided, therefore, that all women would be transferred out of the battery manufacturing area unless they could prove they were no longer able to bear children.

Transfer for Norma James would have meant either less pay or loss of the steady afternoon shift that allowed her maximum time with her kids. So, unwillingly, she had a tubal ligation.

In a similar situation at the Bunker Hill Co. in Kellogg, Idaho, management suddenly decided that 37 women would have to be transferred from the lead smelter unless they could prove they were no longer fertile. To top it off, all 37 were herded on a bus one morning and taken to a clinic for pregnancy tests. Nine of the women refused to have the test and were fired. When their union intervened, the company agreed to reinstate them with back pay if they could provide proof from their own doctors that they weren’t pregnant. One woman capable of bearing children was barred from returning to her job in the smelter, even though her husband is sterile.

Thanks to a job re-evaluation that had nothing to do with the transfers, all the women now are earning as much or more than they did while working in the smelter. But subtle inequities persist. One woman transferred to the drill shop retained her grade 4 pay status, while the other employees in the shop—all men—are paid at the grade 10 level for doing the same job.

These cases are part of an alarming trend toward penalizing women because they are biologically capable of bearing children. And it’s all being done under the guise of “protection.” In reality, such industry policies leave working women, many of whom must work to support households, with some incredible choices: their jobs or their fertility, their jobs or their right to privacy, their jobs or their dignity.

The issue takes on scary dimensions in light of a recent estimate by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: some 1 million of the 16 million women workers of child-bearing age are exposed to chemicals that could harm the fetus. If large companies succeed in discriminating against these women, some labor leaders believe, every woman of child-bearing age is in danger of being “protected” right out of a job.

The issue takes on scary dimensions in light of a recent estimate by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: some 1 million of the 16 million women workers of child-bearing age are exposed to chemicals that could harm the fetus. If large companies succeed in discriminating against these women, some labor leaders believe, every woman of child-bearing age is in danger of being “protected” right out of a job.

Policies that infringe on the reproductive rights of female workers are, of course, morally distasteful to many women. “A woman should not have to choose between having a job and having a baby,” says Ann Trebilcock, an attorney with the United Auto Workers.

These policies are not only unfair; they’re also illegal. Requiring female employees to prove they are infertile, or to have pregnancy tests, or to sign a statement saying they will not have more children, imposes on women a condition of employment not imposed on men. Thus, it violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits sex discrimination in employment.

Such requirements also are at odds with the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act, which guarantees “every working man and woman in the nation safe and healthful working conditions.” This Jaw puts the burden squarely on the employer to provide a workplace safe for all workers -not just men, not just infertile women. The fact is that much of industry is not complying with the Jaw.

“If industry were meeting current safety and health standards under the Jaw, it would go a long way toward alleviating the problem of hazards to fertile or pregnant women,” says Dr. John Finklea, head of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Industries argue that special precautions are necessary to protect unborn children. With her reproductive organs intact, a woman could become pregnant, even if she says she doesn’t want to. Also, she might not be sure of it for four or five weeks or longer. It is during these early weeks of pregnancy that the developing organs of the fetus are especially vulnerable to a variety of chemicals and metals that can cross the placenta. The most obvious birth defects stem from exposures in the first three months of pregnancy.

So the Lead Industries Association, for example, came up with a tidy solution: Don’t employ “fertile, gravid (pregnant), or lactating females in the lead industries until such time as adequate information has been developed regarding the effect of lead.” Unfortunately such high-sounding recommendations ignore the reams of information already available on the effects of lead. Decreased fertility and high abortion rates among women workers exposed to lead were well documented 80 years ago.

Dr. Harold Gordon, medical director for Dow Chemical Corp., flatly says that fertile women should not be hired in jobs where they might be exposed to any substances known to cause birth defects in humans. When pinned down, Gordon says he would limit such a policy to a couple of drugs, such as a measles vaccine that his company makes. But many women, all too familiar with corporate discrimination in the past, are understandably fidgety about any talk of exclusion.

Industries apparently are so fearful of ending up with a latter-day version of the thalidomide babies that they are willing to flout the Jaw. Dr. Norbert Roberts, medical director for Exxon, puts it in a nutshell: “We’d rather face the EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) than a deformed baby.”

Why is industry so nervous about this particular issue? Beneath the moral righteousness, there are some solid legal reasons why companies want to be careful.

Birth defects suffered by the child of a worker would not be covered by workers’ compensation, so monetary awards resulting from a lawsuit could go sky high, as in a personal injury case.

Also, even if a woman knowingly accepts the risk and continues working with hazardous substances during pregnancy, she cannot legally release the company from liability on behalf of her child. A child who suffered ill effects as the result of prenatal exposure to job hazards could sue his mother’s employer at any time up to about three years after he reached legal age—18 or 21 in most states. (In personal injury cases, the legal statute of limitations does not start until the age of majority, even if the injury occurred during infancy.) Since most companies do not relish the idea of two decades of potential liability, they want to make sure that women working with certain substances definitely will not have children.

So far, there have been no sensational lawsuits arising from birth defects caused by the mother’s job. In fact, proving that deformities resulted from a mother’s exposure during pregnancy would be extremely difficult, if not impossible. But industry fears a litigation minded public that it believes would quickly pounce on another source of juicy lawsuits. Businessmen cite the soaring number of medical malpractice suits and product liability suits as evidence of a “sue-the-bastards” attitude loose in the land.

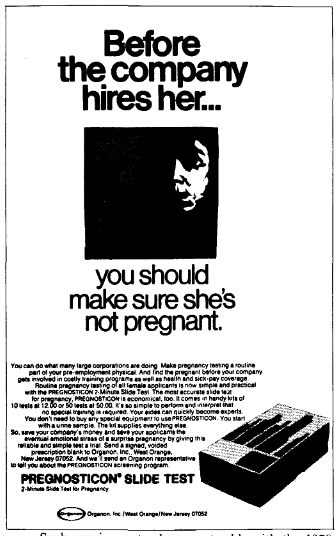

To many people, the new emphasis on “protection” also reflects some long-held attitudes about women in this society. Such as the “pregnant-unless-proved-otherwise” view that lumps all fertile women into the category of prospective mothers.

Sylvia Krekel, an occupational health and safety specialist with the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union, points out that there is still a strong ingrained prejudice against women leaving the home and a genuine fear of women taking jobs away from men. In times of high unemployment, like the present, it becomes easy for industry to usher women out of jobs under the guise of “protection.”

It is ironic, though, that the overwhelming concern with protection doesn’t extend to the traditional “women’s jobs.” Recent studies have shown, for example, that nurses and anesthetists exposed during pregnancy to anesthetic gases that leak from hospital operating room equipment have 1.3 to two times the incidence of miscarriages and birth defects among their children as do women who did not work in operating rooms.

“I have a feeling that no one would seriously suggest that we remove all women of child-bearing age from the operating room,” says Claudia Prieve, an industrial hygienist with the United Steelworkers. “Women as operating room nurses and anesthetists are too well ingrained into our system. After all, who would hand the doctor his scalpel and wipe his perspiring brow? ”

“Contrast this with the plight of the women in the lead smelter or battery plant where there are jobs that pay well and a plentiful supply of men to fill those jobs. There have been very few women in smelters in the past. Why change now? So society says, ‘We’re going to keep those women out of there for their own good.’ How often men mistake their prejudice for the laws of nature!”

What really blasts holes in industry arguments is mounting evidence that, lo and behold, the threat to the unborn is not just a woman’s problem. The male contributes as much to the make-up of a new human being as the woman does—hardly a biological secret. So, if a man works with a chemical that alters his chromosomes (which carry genetic information), affects the number, quality and mobility of his sperm, hinders his sexual performance or makes him sterile, the effects on future generations are very real.

There is evidence that wives of workers exposed to certain substances—women who never had direct contact with those substances—experience reproductive problems. Wives of male operating room employees, for example, had 25 per cent more miscarriages and birth defects among their children than did women who had no link at all with anesthetic gases. In another study, wives of men who worked with vinyl chloride, a key ingredient in plastics, had a significantly higher fetal death rate than did a control group. As far back as 1914, scientists documented the danger to pregnant wives of house painters in one town who regularly inhaled the fumes of lead-based paints. Of 467 children born to the painters’ wives, 23 percent were stillborn. The rate of stillbirths for the entire town was 8 per cent.

There is evidence that wives of workers exposed to certain substances—women who never had direct contact with those substances—experience reproductive problems. Wives of male operating room employees, for example, had 25 per cent more miscarriages and birth defects among their children than did women who had no link at all with anesthetic gases. In another study, wives of men who worked with vinyl chloride, a key ingredient in plastics, had a significantly higher fetal death rate than did a control group. As far back as 1914, scientists documented the danger to pregnant wives of house painters in one town who regularly inhaled the fumes of lead-based paints. Of 467 children born to the painters’ wives, 23 percent were stillborn. The rate of stillbirths for the entire town was 8 per cent.

In light of these findings, should men also be required to prove their inability to reproduce before being allowed to work with certain substances?

To many labor experts and scientists, the solution is obvious: Make the workplace safe for all workers. Sheldon Samuels, a health and safety specialist with the AFL-CIO, maintains that the government should set standards to protect both sexes against even the slightest effect on any organ of the body. The fetus and the reproductive system would automatically be included.

It sounds simple, but in the real world of too little research and too much government foot-dragging, such standards will be a long time coming.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the agency charged with implementing the federal safety and health law, sets and enforces specific standards in all kinds of workplaces. But virtually all the standards now on the books were adopted from old “consensus” standards drawn up by industry dominated groups and designed, at best, to protect most workers most of the time. Because of pressure from industry and the go-slow attitude of recent administrations, OSHA has issued only a handful of new health standards during the five years it has been in operation. None contain any consideration for the fetus, which can be harmed by toxic chemicals the mother inhales, even though the mother herself may suffer no ill effects.

The government argues that it doesn’t have enough solid data on which to base stricter health standards that could stand up in court. No wonder. Very few of the 20,000 chemicals commonly found in the workplace have been tested for their effects on the unborn. Consequently, only about 20 substances so far have been clearly linked with birth defects and miscarriages.

Another problem is that women routinely have been ignored by the occupational health researchers. Dr. Vilma Hunt, a Pennsylvania State University epidemiologist, points out that scientists often “simplify” their studies by limiting them to men. She notes that in one of the few national surveys that did include information about employment during pregnancy, women were not even asked what job they held. Their husband’s occupations, however, were carefully noted.

Until the law is more strictly enforced and better standards written, some labor leaders argue, American industry should adopt the policies of such countries as the Soviet Union, where pregnant women are transferred with no loss of pay or seniority to jobs where they will not be exposed to dangerous substances.

Unfortunately, such an approach is unrealistic in this country where 87 per cent of all women workers are not even represented by labor unions and consequently are powerless to demand transfers. Also, transfers are unreliable because dangerous exposures could occur before a woman knows for certain she is pregnant. And while such a policy would deal somewhat with hazards to the fetus, it ignores working husbands who may pass on genetic defects to their offspring and working women who do not want children but who may be barred from well-paying jobs because they are of “child-bearing age.”

Nevertheless, as more women enter the labor force in a wider variety of occupations and as evidence of job hazards continues to mount, society will have to face the issue of protecting both today’s workers and future generations. Clearly, the solution is not a simple matter of denying jobs to those who might be more susceptible to harm. Dr. Bertram Carnow, professor of occupational and environmental medicine at the University of Illinois School of Public Health, sums it up well:

“Considering the evidence about effects of toxic chemicals on the reproductive systems of both women and men, we either end up with workplaces full of 60—year-old eunuchs, or we eliminate the hazards. I think it would be easier to eliminate the hazards. “

Phyllis Lehmann is a Washington-based writer who specializes in occupational health.

This article first appeared in the Long Island, N.Y., newspaper, Newsday, and is used by permission.