This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Fighting Nukes at Seabrook

by Tedd Judd, Betsy Walker, & Frank Bove

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 9, No. 4, July-August 1977, p. 20–26

Following are two articles by SftP members who were among the 1,400 people arrested for occupying the site of the proposed nuclear reactor at Seabrook, N.H. this past May Day. Although all three were jailed in the same armory, their interpretations of the events significantly differ.

I. Lessons from Seabrook

When we were asked to write about the Seabrook occupation we decided almost immediately to discuss our personal experiences and how they altered our political goals and attitudes. This is an important but neglected topic. It concerns the reasons that people join and leave our groups and actions and hence the very strength of our causes.

When we went to Seabrook we expected to stay for the weekend, get arrested, and return home by Monday. As it turned out we stayed two weeks at the expense of jobs and personal obligations. Why did we stay? Certainly the daily news reports showing our successes were important. But even more significant were the experiences which taught us about the relationship between the means and ends of a political action.

The proposed tactics for the occupation attracted us to participate because they clearly expressed our intentions. We wanted to stop nuclear power, so we sat on the construction site to prevent the building of a plant. This action provided a message for the press and the public which could not be misinterpreted. In addition, we wanted to dramatize to the larger public the need, the means, and the possibility of determining our own energy policy. As it happened, our action also allowed us to illustrate the government industry alliance which resists public participation. The clarity of these statements made it personally rewarding to participate.

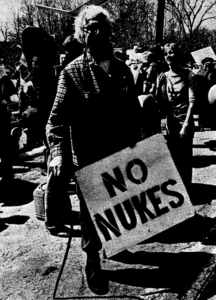

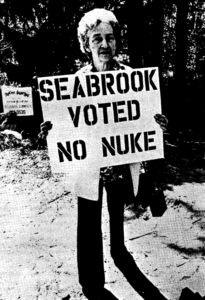

Photographs by Ellen Shub: The photos of Seabrook on this and the following pages were taken by Ellen Shub, a Boston-based freelance photographer who has been documenting people’s movement struggles since 1973, particularly those involving feminism, health care, and environmental issues.

But it was the common daily experiences of the occupation which let us see more clearly how the personal is political. Two thousand of us came to Seabrook with one stated common goal, to stop nuclear power without using violence. Beyond that, each of us came with our own individual political goals. But we found as we worked together that these goals also often became common ones.

Our affinity group of sixteen people was typical of many. We first got together a week before the occupation for a five-hour session of non-violence training led by organizers of the occupation. A few of us knew each other, but most of us were strangers. We found at that meeting and at the one other we had before the occupation that we had widely differing amounts of political experience. It was the first demonstration that some people had attended; it was the first arrest for most, including the two of us. Some of the people there were concerned primarily with the issue of nuclear power and its dangers, while others believed that nukes are just one more product of an elitist, profit-seeking system. By the end of the experience, all of us understood more clearly the ties between the nuclear power industry and the state. This awareness spurred on our attempts to evolve decision-making processes which are radically different from those of our capitalist society.

Nowhere were these attitudes better expressed than in the consensus process. Here votes came near the beginning of a discussion, rather than at the end as in a majority rules system. Minority opinions, caucused into alternative or additional proposals, sometimes significantly altered the majority proposal. Always the result was a compromise which everyone could accept. This method was used even when severe time pressures made the majority rules system extremely tempting. But sensitivity to individuals did not get in the way of our actions, and the resulting affirmation which came from sticking to the consensus procedure added immeasureably to our solidarity and spirit.

All positions of responsibility were rotated, often daily, including facilitators (chairpeople) of the meetings, representatives to speak with the media, and affinity group spokespeople. These positions were open to all volunteers, although sometimes tempered by the decisions of a group: for instance, the media committee weighed carefully the democratic balance of press conference teams. Slowly, those with greater skill at a task learned to train those with less experience and to appreciate and seek their contributions.

Respect for individuals was a priority throughout, with a special effort to eliminate sexism. Women were well represented in the rotations of all positions. Usually the facilitator of a large meeting made a point of asking for opinions from people who had not yet spoken. When this failed to happen, the regular business of a meeting was often stopped by someone crying “Process!” and pointing out that a woman had been quietly holding up her hand for several minutes while more vocal men had been quickly called upon. Facilitators who found themselves unable to cope with both the content and the process of a meeting occasionally stepped down and let someone else facilitate for a while. In smaller groups, too, the less articulate were encouraged to speak. Sometimes this brought out new alternatives, sometimes it cleared up misunderstandings. The elimination of sexism could not, of course, be accomplished in a few days, and women still sometimes felt the need to get support by forming groups for women only.

Our process was also helped out by an openness to criticism among both friends and strangers – we came to offer, accept and seek comments on individual behavior in meetings. Criticism and self-criticism were also institutionalized: each person had a chance to comment on the meeting of a small group at the end without fear of rebuttal. In larger groups time was set aside for evaluation comments.

Our decision-making process was made much more personal, enjoyable and efficient by the frequent use of small groups. Most major decisions were first discussed by everyone in groups of 5-20. This gave all a chance to air their views, clear up misunderstandings and hear a variety of opinions. It refined and weeded out proposals and provided everyone with preliminary thinking which greatly sped the mass meetings. At first, this was done by affinity groups, but as arrest and arraignment broke up groups we found it first necessary and then desireable to form new groups. Towards the end, arbitrary groups were formed for each discussion and this exposed us to fresh opinions, let us meet new people, and increased our -feelings of unity with the whole group.

Our community in the Manchester Armory (also known as Personchester or New Freebrook) became remarkably self-reliant. We established a postal service among the five New Hampshire armories where occupiers were staying, a library, an information desk, and a barber shop. Vegetarians ate from an alternative food table established from food we had brought in with us or that was donated by food coops. Health care workers set up a table and dispensed western medicine as well as herbal teas, Chinese Tiger Balm, and goldenseal ointment. A fine arts center with watercolors and scissors kept people busy for hours painting banners, pictures or faces. The large cardboard boxes our cots came in rapidly became kiosks, decorations, tables, and private spaces.

We made music at all times of the day with guitars, recorders, kazoos, and especially with our voices. We sang political songs, friendship songs, and songs written just for the occasion. Usually our daily town meetings started with singing, and when they got tense we sometimes broke the tension with music. Once we sang songs to drown out the loudspeaker as we resisted when they tried to take several of us to trial with inadequate time to prepare, and we celebrated that victory with song. We had dances, talent shows or theater almost every night at which we spoofed our meals and meetings, our fears and frustrations. All of these things created a very real sense of togetherness and friendship among the people in the armory. From this sense came our confidence and our political strength.

But life in the armory was by no means light and easy. There were times for all of us of fear, loneliness and frustration. Seven hundred people in one room can be fun, but the lack of power to leave the room and to find solitude and quiet produced a tension in all of us. Usually, however, we were unhappy at different times from our friends. People who had been strangers a week before gave us support, ears, hugs and an incredible amount of trust. When they needed it, we gave it back to them.

Every day a few people bailed out of the armory to get back to jobs, exams, family or other commitments. It was hard for them to leave our community with the shared values and the trust we had built up in each other, and it was hard for us to watch them leave, returning to outside friends and freedoms. Whenever a person left, escorted to the door by her affinity group, everyone else stopped what they were doing to applaud the leaving one in thanks for what she had given.

We learned a lesson at Seabrook which is as vital to our political effectiveness as it is to our personal satisfaction: our goals for society ought to be reflected in the functioning of our political activities. By gaining experience in groups which are maximally responsive to all individuals, we are doing more than serving ourselves; we are providing an example and a precedent for a better organization of the workplace and of other social institutions.

—

Tedd Judd works in clinical and research neuropsychology in a Boston hospital. He is a member of the Sociobiology Group of SftP. He is a feminist with interest in human rights and the behavioral sciences. Betsy Walker worked in neurobiology labs for several years. She is now becoming increasingly interested in nutrition issues, and is a member of the Food and Nutrition Group of SftP. She has also worked on the editorial committee of the magazine and on women’s issues within the organization. Both Tedd and Betsy plan to continue their work with the Clamshell Aliance.

II. Whither Clam?

I have been a member of the Boston Clamshell Alliance since March of this year. I was arrested at Seabrook, N.H., and spent ten days in the Manchester Armory. Being a socialist and a member of the Science for the People Energy Group (Boston), I had to grapple with the problem of working as a socialist in a reformist, “mass” organization. What follows are observations on Boston Clam’s political strengths and weaknesses based on my work in Clam, my experience at the Seabrook site and in the Manchester Armory after the occupation.

Clamshell Alliance is for the most part a young, white, middle-class organization. Like the anti-war movement, there is a hodge-podge of political viewpoints. There are liberal environmentalists who are primarily worried about pollution. There are philosophical pacifists (eg. American Friends Service Committee and other Clam Quakers) who devoutly believe in passive, non-violent action, and who have marched on numerous occasions against war and the war industry. The Clam Quakers are for social change, but not all are explicitly anti-capitalist. They avoid such words as “socialism” and “working class.” They also constitute the majority tendency in Clam right now.

I am among the Clam members who are openly socialist. We have our disagreements, but we all agree that Clam must make an all-out attempt to reach out to unions and progressive community groups (e.g. tenant groups) in order to broaden its base and organize working people and minorities. Unlike some reformist organizations, Clam is not hostile to socialists. All socialists who oppose nuclear power and agree to participate non-violently in Clam actions are welcome. I am now working with Clam’s Resource Committee preparing a pamphlet on jobs and energy. Clam supported my efforts to form a new committee to do outreach among unions and progressive community groups. Thus, my experience seems to indicate that socialists can play an active role in shaping Clam’s direction as well as put forward an explicitly socialist analysis of nuclear power and energy issues in general.

The major problem for socialists in Clamshell is the organization’s political passivity towards broad based organizing. Specifically, our task is first, to convince others of the importance of broadening Clam’s base and of linking up with other progressive struggles, and second, to push Clam to place major emphasis on actions and activities which will accomplish these aims.

The Politics of Example

Clamshell’s strategy against nuclear power has been to occupy the site by nonviolent direct action or civil disobedience. This strategy distinguishes Clam from other antinuke organizations in the U.S. who have fought nuclear power in the courts and at government regulatory hearings. Clam hopes to organize a grassroots movement by its direct action tactics. But there is, at present, a majority tendency in Clam which sees direct, non-violent action primarily as a way of “setting an example” and “expressing one’s conscience.” This “politics of example” has taken precedence over grassroots community organizing.

At Seabrook, we were all concerned with organizing ourselves and maintaining a non-violent occupation. It was true that we were to some degree cooperating with the legal authorities during the occupation, but we were also breaking the law. Once the arrests occurred, however, many of the occupiers transformed themselves into passive, obedient, self-denying Clams. I believe this transformation resulted from l) lack of adequate planning by Clam, 2) the general political immaturity of many occupiers, and 3) subtle, and perhaps not deliberate, manipulation by Quaker Clams whose opinions prevailed in the face of the lack of political experience of most occupiers and the confusing situation in the armories.

First, Clam had done an excellent job of planning the occupation itself, and I believe the entire operation was for the most part successful in stimulating the anti-nuke movement. But, Clam was not really prepared for the long imprisonment. None of us really thought we would be in jail so long, nor did we expect that our rights as prisoners would be denied. We were confused, ill-prepared, and this led to our initial passivity. Hopefully, next time we will be ready to take action quickly to demand our rights.

Second, there was a general lack of political understanding among the occupiers. The majority seemed to underestimate the power and determination of the nuclear conglomerate. They seemed to believe that setting an example by staying in the armories indefinitely, setting up a “model” community, and generally cooperating with the National Guard, would show our determination to stop nuclear power. They believed that this was the most important action we could take. I could not see how this “action” was supposed to change the minds of Governor Thomson, the heads of GE, Westing house, the utilities, and other multinationals, the huge financial institutions, universities and think tanks which have all invested heavily in nuclear power.

Many thought that Thomson was the main enemy and that changing his mind would be enough to stop the Seabrook plant. They had all forgotten the defeated initiatives in other states, the massive media blitzes of the energy giants, and the Carter program which called for a nuclear speedup. They had little political sense of the forces against them, nor did they realize that without worker support, the movement against nuclear power will be soundly defeated.

A small group of us fought against this “Woodstock fever.” Sure it was great to play music, work out our feelings, sing and dance together! But we argued that this community spirit had to be organized in our own neighborhoods. The most important action we could take was not to build a “model” community in the armory, but to get out of the armory and organize. Organizing a model community in the armory was relatively easy. There was little cultural or class diversity. The real test is building model communities in the Boston and other metropolitan areas.

Confusion around the struggle for our legal rights hampered our efforts. Should we cooperate fully with the National Guard? Or should we force the state’s hand by noncooperation? the majority was for complete cooperation. In the begining, I was for limited cooperation, which meant that we should demand our rights, but not confront the guards. It soon became evident to me and others that · this strategy would not succeed. We began to push for non-violent confrontation and non-cooperation to force the state to grant us our rights. We spoke out against the passivity which seemed to adhere to the majority’s notion of “non-violent action.” Instead of worrying about being nice to the guards, we were more interested in linking our struggle with struggles in other prisons for prisoners’ rights. Instead of hobnobbing with the General of the National Guard, we talked to one of the guards who was involved in a strike-boycott against a supermarket conglomerate and spread the word throughout the armory.

Finally, I want to make a stab at analyzing the role of the Quakers in giving Clamshell its tactical direction. The Quakers, in general, and a group called the Movement for a New Society (MNS), specifically, filled the leadership vacuum in the armory largely because they were more organized and experienced in non-violent action. They played an important role in maintaining peace, and they were very sensitive to people’s needs and anxieties. However, through a complex process, they also forced (consciously and unconsciously) their positions on the group, creating a stifling “solidarity.”

Being one of the minority of dissidents I want to be self-critical also. We did not organize ourselves nor did we adequately caucus with other Clams to get our ideas across until too late. Instead, at the large meetings we expressed our anger and frustration because our positions were being rejected by the majority. This was our mistake.

The Quakers were primarily concerned with diffusing anger to prevent chaos from breaking out. But these tactics were also a good political move by them because they isolated the dissidents and made them look like “disrupters.” Whether the Quakers were aware of this subtle manipulation or not, I don’t know. It is important to be able to reduce tension at meetings in order to deal with the politics behind the tension. But what happened was that after the tension was relaxed, discussion about the issues which produced the tension did not take place or was inadequate. We were isolated; our anger was stifled, or it was considered illegitimate or even dangerous, and the passive tendency remained in control.

The majority, in this case, supported passive non-violent action as the best tactic against nuclear power because it allows one to express one’s conscience and set an example for the world to see. But who conveys that message to the world? Can we trust the media? Obviously not! More importantly, is this type of political action capable of attracting worker support, or is it more likely to gain the support of students and “weekend warriors?” These are the questions which have come out of the spectacular success of the occupation. It is time for. Clam to rise to a new level of struggle.

—

Frank Bove, formerly the office coordinator for SftP, is an active member of the New American Movement, SftP and the Clamshell Alliance