This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Jobs and the Environment: A National Conference

by Marian Lowe and Paolo Strigini

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 4, July 1976, p. 26–31

The authors of this article participated in the National Action Conference Working for Environmental and Economic Justice and Jobs. They presented some data on the controversial issue of appropriate technology, particularly with respect to capital intensity and labor intensity. Throughout the conference they represented the point of view of Science for the People, although they were officially designated “environmentalists from Boston University.” The following is a personal view, with some immediate reflections and constructive criticism.Paolo Strigini is a molecular biologist who has been a member of Science for the People since it started in 1969. He has done research and teaching at Harvard and Boston University and is currently unemployed. Marion Lowe teaches chemistry at Boston University. She is interested in problems involving energy and is active in the women’s movement.

From the 2nd to the 6th of May, about three hundred people from labor, community and environmental organizations met at Black Lake (the Walter and May Reuther UAW Family Education Center) in northern Michigan. Within each group there were officials and some rank-and-file members, social activists and bureaucrats. Special care had been taken to invite non-white and women representatives, although, except for community people, few of them were in prominent positions within their own groups. The atmosphere of those four busy days was somewhere in between a parliament, a convention and a radical meeting. With people hurrying from a general assembly to a caucus, or from a workshop to a personal and intense discussion with old or newly acquired friends, it was good to remind oneself that what looked like a modern high-class campus was in fact a study and meeting center and a vacation resort for auto workers. (It was not so good to learn that the services for the conference was managed by Sheraton—an affiliate of ITT.)

The conference was sponsored by an impressive number of both large and small, national and local, well-established and grass-roots organizations. It was planned by organized labor, community and consumer groups, and by government and private environmental groups.1 It was structured into three types of gatherings: general assembly, core groups, and workshops or caucuses or task forces, meetings of the first two types recurring every day. The core group deserves some explanation, because of its novelty and its success. Each conference was assigned from the beginning to a particular core group, designed to include fifteen to twenty people of different sex, race, education, profession and residence. Thus each core group provided a sample of the general assembly, where conferees through repeated meetings gradually got acquainted with each other. People who had been listening most of the time had a chance to express their thoughts and goals, sometimes their frustrations and anger—many did. Those who had been doing most of the talking had a chance to listen—we don’t know how many did. Misunderstandings and real problems emerged in the core groups—sometimes in advance of the general assemblies—and a real dialogue took place between different people, which helped both subsequent talking and listening.

Different Points of View

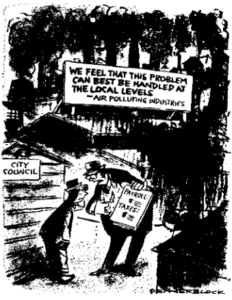

Sunday evening UAW president Leonard Woodcock opened the conference by speaking to the first general assembly. He contended that the dilemma between jobs and a healthy environment is a false one and that the reality under the apparent conflict of interests between labor and environmentalists is the environmental blackmailing on the part of the bosses. This happens when businessmen threaten to close or move away their plants—thus taking jobs away from the community—unless the environmental regulations which they violate are lifted or not enforced—thus perpetuating ecological abuse. Workers’ antagonism and resentment toward environmental issues has been fostered by those environmentalists who, while discovering pollution in streams, woods and residential areas, are not paying enough attention to the health hazards in the factories where pollutants come from. Environmental blackmail has been kept alive by national and local politicians—such as those labeled “the Dirty Dozen” in Congress by Environmental Action—who are not only opposed to any environmental regulation, but are also staunch enemies of labor.

Woodcock reminded the conference of the efforts of the UAW against the SST and the Concorde, against the nuclear program, against the abuse of pesticides (together with Chavez and the Farmworkers) and other toxic substances in the plants (together with other unions). He stressed the need to implement the right to have a job as part of a national economic plan (Hawkins-Humphrey bill) and the need for new legislation to protect workers and communities from environmental blackmailing. It became clear, however, in subsequent talks and during discussions in the core groups, that much work was still to be done in order to achieve unity among workers, community and environmentalists.

Monday started with a panel discussion. National Public Radio reporter Barbara Newman introduced the panel with some provocative remarks, particularly directed toward organized labor and traditional environmentalists. She reminded the conference, for instance, of the alliance between business and AFL-CIO officials to promote nuclear power before the California referendum. The panel included a community representative, Gale Cincotta from National People’s Action, environmentalist David Brower of Friends of the Earth and AFL-CIO assistant to president Meany, Tom Donahue. They looked, respectively, like a strong, working-class mother, a benevolent wealthy professor, and a shrewd bureaucrat-politician, and that’s how they sounded as well.

Cincotta pointed out the need for far-reaching national and local plans to rehabilitate rundown neighborhoods, which require money, action, and knowledge of the problems. She emphasized the importance of fixing up old houses and old machines (including cars, refrigerators, washers and fixtures) rather than priding ourselves on new flashy ones that the poor cannot afford. Brower drew an apocalyptic picture of a nuclear economy, leading to a broken-down unhealthy planet, where people would probably live an unhappy slave-like existence. Such real danger for humanity on the brink of nuclear disaster he traced to lack of awareness and courage on the part of politicians and labor, the rich and the poor. Donahue reminded the audience that American unionism is primarily concerned with promoting higher pay and healthy jobs through collective bargaining: it does not make social policies and does not concern itself, except marginally, with social issues. He pointed out that AFL-CIO does not have a policy of its own, independent of its affiliate unions, and admitted that some of these may diverge or conflict. He exalted the virtues of economic growth for cancelling economic differences and satisfying social needs, as he said happened before the present recession, and he appealed to labor, business, and government each to do its own job, so that growth can resume.

That economic growth is no panacea, however, was the main thrust of ecologist Barry Commoner’s talk in the afternoon. The picture drawn by Commoner with historical perspective, hard facts and humor, showed how economic exploitation, unemployment, political false promises, problems of energy supply and environmental abuse are all bound together. He outlined the postwar trend in corporate America to ever greater use of capital and energy (with increasing waste of natural resources and pollution of land, cities and factories) at the expense of jobs. This is the consequence of our economic system (geared to maximize profit) determining our mode of production in such a way as to come up against inflexible ecological constraints. Therefore, Commoner contended, what is needed is a new economic system: socialism. This is the only way, he said, to solve our environmental and economic problems in harmony—and it is a solution which is not necessarily inconsistent with our democratic tradition.

The conflict between jobs and the environment within the present economic system, typified by Donahue and Brower, emerged in the questions and discussions after the various talks as a division within both the labor and the environmental movements. Labor officials, in particular, felt the pressure to advocate jobs for their constituents. The large majority of those present, however, rejected Donahue’s narrow view that “nuclear energy is the way we are going; and we need jobs”, even though not all were prepared to struggle for the “non-nuclear future” advocated by Brower. Some workers commented: “Donahue is selling out”, while some environmentalists admitted: “Brower is insensitive to labor’s interests and history”. Many people, however, agreed with Commoner’s analysis and with his conclusions that environmental and economic problems must be solved together in a new way. Some had reservations concerning the implementation of a new economic system: “We have to change things in a democratic fashion”; “One thing at a time”; “The word socialism will bother some of my members”; “Socialism is a point of view rather than a blueprint”. Others said, “He didn’t call for socialism loud enough”. The need for a concrete socialist analysis and program was very clear during this discussion.

Two more immediate and related problems for the conference surfaced in discussions and core group meetings. One problem was the ambivalent positions taken by environmentalists. The other was the lack of space left for community groups in the ongoing debate between labor and environmentalist leaderships. Cincotta had explicitly accused the environmental movement of elitism, and implicitly charged labor with political insensitivity in her talk. These charges remained unanswered.

Full Debate and a Case Study

Tuesday was workshop day. Each workshop was intended to bring together some political and economic analysis, some technical information and some organizing experience and program. The list of workshops offered was impressive. They could be grouped—somewhat artificially—in three main categories: (1) labor problems: impact of conservation and recycling on jobs; in-plant environment; funds for retaining and replacement of workers; toxic chemicals; etc. (2) community problems: transportation and welfare policies; fund raising; use of the media for local organizations; possible changes in the rate structure and ownership of utilities; housing; paying for pollution damage or clean-up; (3) general policy problems: energy options and conservation policies; economic growth vs. population and poverty; alternative economic and technological policies. A complete set of reports from workshops—and other meetings as well—is being gathered by the organizing committee of the conference [for further information, write to UAW]. Despite the stated purpose of integrating technical information and political economy with concrete organizing experience, the actual balance achieved in the various workshops differed. Perhaps it would have helped to maintain the balance, if each workshop had been moderated by two persons: one labor and one community representative. As it was, it turned out in some cases to be environmentalists talking to each other. This probably happened for various reasons: the difficulty of determining in advance what labor and community people wanted to hear; in some cases, the lack of interest on their part in theoretical issues; and in most cases the lack of sensitivity on the part of some environmentalists for people’s main interests and concerns. Environmentalists altogether were the most articulate and the most numerous of the three groups at the conference. Some saw themselves as experts and expected to be listened to and to be asked respectful questions; unfortunately some workshops were set up in such a way as to encourage, rather than make impossible, these attitudes.

This disturbing impression from the morning workshops was strengthened by the panel discussion on the Mahoney River Valley, which was presented as a case study in the afternoon. The panel: a conciliatory EPA administrator, a militant environmentalist lawyer, a liberal businessman for community economic development, a bureaucrat representing the local unions (or the companies?) and the Director of the Sierra Club, another lawyer, acting as moderator. The case: a set of ancient steelmills in Ohio, disturbed by the recently passed Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, had threatened to close, with consequent economic disaster in the area. The plants were perhaps only marginally profitable before the environmental regulations were passed (no one can read their books), and the steel industry claimed that they could not possibly comply without losing money. The compromise solution: a temporary local suspension of the most demanding clean water standards.

It was a very interesting case. In the first place, it involved the definition of the job of the EPA—is it just to enforce the laws protecting the environment or is it to get involved in value judgements concerning the economic consequences of such laws, and whose interests should be protected against their rigorous application. As the moderator reminded us: “Hard cases make bad laws” (or bad precedents). Further, this case may result in a situation apparently without any winner. Environmentalists saw a victory for business due to the EPA selling out. Some, if not all of the plants, however, may close anyway; and the community representative looked with anxiety at the future for business. The labor representative, on the other hand, claimed a “victory” for the people in the region. The steelworkers and the community as a whole, in fact, stand to lose something no matter what happens—they either have insecure jobs in a polluted environment or no jobs at all. There is plainly no guarantee of how long the plants will stay open, no plan for replacement, reinvestment or development, no power on the part of the workers and the community to obtain some guarantee or some plans from the industry and the government.

The Mahoney Valley controversy illustrates the insoluble contradictions that arise when the options presented are too narrow: in this case, jobs against environment. Some environmentalists and labor people suggested that there should be laws preventing plants from closing as a response to environmental regulation. Yet, how long can a system based on profit afford to keep nonprofitable businesses operating, no matter what social issues are involved? The real problem is how to develop a new system in which environmental issues, jobs and other social concerns become the fundamental aspects of a democratic planning process.

A Change of Focus

The only scheduled assembly for Wednesday included talks by Russell Peterson, Chairman of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, and William Hutton, Director of the National Council of Senior Citizens. Peterson’s talk still focused on the environment-job conflict. He noted that, while hot water and cool air can be bought by dollars, dean air and water—as well as other environmental rights—can only be secured by votes. He stated that 300,000 more jobs were created than lost since 1971, by enacting and enforcing environmental regulations. He stressed the need for adequate funding, however, both to pay for new jobs and to ensure the necessary retraining programs which would avoid environmental blackmailing and bidding of different local and business interests against each other. Hutton dealt more with community concerns as he discussed problems of senior citizens. He pointed out that others should keep in mind the political potential of senior citizens and the senior citizen movement. These people have time, commitment and numbers and they are future-oriented. He strongly suggested that other groups should contact them for joint efforts.

The focus for the first two and a half days had been predominantly on the conflict of interest between organized labor and environmentalists. Several social activists from all groups, and especially community organizers, had been voicing frustration that the discussions and talks did not deal with the big structural questions or with specific action proposals which were important to the poor urban and rural communities, the minorities and the unorganized workers. Such frustration, concerns and demands took shape in special workshops, caucus and task force meetings from Tuesday evening through Wednesday, such as those dealing with the strengths and weaknesses of the Hawkins-Humphrey bill, the urban environment and rural America.

A briefing on the H-H bill was held Tuesday night and a task force kept working on it the next day. The bill proposed by Hawkins, a Black representative from California, and supported by Senator Humphrey—is intended to make full employment a mandatory goal for the federal government. It also directs Congress to enact a national economic plan in order to correct the business cycle and to achieve full employment. The latter, however, as officially defined, allows a rate of marginal unemployment of 3% (already stated in a 1946 Act). It is likely, then, that non-whites, women, youth and the unorganized will carry the burden of the official unemployment statistics, even during non-recession years. Therefore it was agreed during the discussion that the projected economic plan must contain concrete provisions for education, training and financial help to individuals, cooperatives and community enterprises, directed at eliminating those pockets of chronic unemployment. It must keep business from taking advantage of the subsidies and other facilitations provided by the plan, and keep the military or other government or business bureaucracies from monopolizing the public work programs for their sectorial interests. It was pointed out that unemployed hired on such programs have been used to break strikes. Finally, the economic plan must include workers and communities in its formulation at the local and national level (and not only the President’s economic advisors, as provided by the bill) and make sure that environmental guidelines concerning human and natural- resources are taken into account in the short and long term.

While all of these recommendations might not be realistically written in a single bill, they are important guidelines for future action. It was important that the conference, while endorsing the general concept of the H-H bill, also expressed its sense of the direction in which we should go and organize for.

Different voices from the Community

The most dramatic expression of community concerns came as a nonscheduled statement from the Black caucus, during the question period after the talks on Wednesday. The Black caucus brought together many concerns of the urban communities and their organizers. It charged the environmental movement with elitism, with not being aware of the effect of environmental concerns on the poor, with often seeking to solve problems in a way that benefitted the middle class. It demanded that jobs for the 3% hard-core unemployed be included in the provisions of the H-H bill, that the impact of environmental laws on low-skill jobs and on the poor be compensated by adequately funded educational and training programs, that decent housing, day-care, health services and transportation be funded and implemented in the poor neighborhoods of the inner cities, that financial help be directed to those in need, while red-lining practices by banks and other lending or granting institutions be penalized—among other things, by unions withdrawing their funds from them.

A joint special workshop convened to reach agreement among environmentalists, labor, and community representatives specifically on the issues raised by the Black caucus statement and, in general, on the problem of economic growth and the poor. There was considerable tension in the packed room, due both to the specific charges made by the Blacks and to the fact that their demands appeared to be directed (sometimes personally) against environmentalists and organized labor. For example, one Black man said “We are tired of educating whites,” and a white woman retorted, “And we are tired of being educated.” Fortunately, a sense of honesty, rationality, and commitment helped relieve the tension. A joint task force continued to work on a resolution concerning economic growth and the poor; their statement on Thursday morning reflected a strong substantial agreement on the demands of the Black caucus. The fact that environmental legislation is often biased in favor of the white middle class and helps maintain the status quo was pointed out by other groups and caucuses, such as the Humphrey-Hawkins task force and the women’s caucus.

Any mention of the problems of women as women was conspicuously absent from the official program. Furthermore, the issue of “environmental and economic justice and jobs” for women was not so easy to raise given the initial narrow emphasis of the conference. This difficulty was another aspect of the problems brought out by the community groups—the need to deal with issues relating to the unorganized and the poor. However, unlike the community groups, strong representation from women as women did not exist. No feminist groups were present—it is not known whether or not they were invited.

Still, a women’s caucus called for Tuesday night attracted about 20 women (out of about 90 to 100 at the conference). Organization difficulties, besides the many other tasks that women had to fulfill during that hectic Wednesday, reduced the task force working on women’s issues to a very small number. The final statement reminded the conference that the problems of women had not been addressed and that they were crucial to any consideration of the issues facing the conference: for example, unemployment hits women harder than men; women make up a large part of poor heads of households; they are a large percentage of the unorganized work force and have difficulty in gaining decent-paying jobs. It called on the women and men at the conference to be aware of and act on women’s issues.

Most of Wednesday was taken up by an incredible variety of special task forces, caucuses and workshops, initiated by conference participants. One of the most impressive reports came from the rural caucus. From the beginning of the conference, small farmers (the National Farmers Union) and farmworkers had been expressing their separate frustrations on the lack of attention to the social and economic problems of rural America. What we heard later from the rural caucus was a comprehensive radical analysis and proposal for action, rather than simply complaints about the diminishing profits in farming and the like. The report advocated a new concept of land tenure and land grants, including implementation of the legal granting of federal land to farmers and farmworkers (limited to 160 acres), a tax based on land productivity to eliminate rent profits, a transformation of agricultural research programs in universities, government or state agencies, which presently help only agribusiness. The problems of rural America became complementary to those of the cities, as soon as people rather than business were at the center of the picture. One set of problems could not be solved without solving the other.

A Starting Point

Thursday morning was for summing up, although no resolutions were submitted for endorsement by a general vote. What happened instead was that each core group, caucus and task force presented its own resolution, statement or action proposal, while the whole assembly listened intently. Then everyone sang “Solidarity.”

The sense of the conference thus emerged, through a variety of different viewpoints, as a substantial unity of goals and a firm general determination to continue and expand the work started at Black Lake. Widespread commitment was expressed to work on problems not dealt with sufficiently, and especially against discrimination based on race, sex or class; to set up a network of local, regional and national resource groups for legal, medical, technical, and financial advice to labor and communities; to organize at all levels strong coalitions—such as people against the utilities—on issues that reflect major and general concern; to organize locally and nationally to fight unemployment, dislocation and environmental blackmailing. One of the most constantly recurring statements was tracing the roots of our environmental and economic problems to economic inequality among individuals and to the mechanism of economic decision-making. Some groups proposed holding public hearings on concrete issues such as the price of electricity, gas or oil, in which the relative merits of capitalism and economic democracy (socialism) could be argued. These hearings were intended to initiate an ongoing national debate aimed at achieving a concrete definition of a socialist analysis and program.

It had been an interesting and intense political and human experience. The organizing committee and the UAW staff had worked with great dedication, sensitivity and intelligence. The result was a schedule which—in spite of shortcomings—made space for a great deal of learning experience and was flexible enough to allow confrontations to emerge, without destroying our growing sense of solidarity, awareness and strength.

It was a sign of strength and. maturity on the part of the organizing committee and the conference that no general compromise resolutions, for example, concerning environmental issues or energy options, were pressed to a vote. Not only would the majority of the conferees have been unable to express any more than their personal opinion, unless their group’s position had been previously formulated, but such votes would have hampered rather than helped all the work which remains to be done together. The importance of the conference was not in making headlines, but in initiating a process of working together for social change on a broad basis and in a progressive direction.

In dealing with many of the issues which were raised at the conference, quite a few environmentalists, especially those from the traditional, well-established groups, tended to stick with technical recommendations and legal proposals. They would then present themselves as experts and lobbyists, and ask others to support them by keeping up the pressure: everyone doing their own job, as Donahue (AFL-CIO) had said. This perspective dominated the first part of the conference and, if it had continued, would have allowed only some political maneuvering and compromising between top labor and environmental representatives. Its supporters and spokespersons avoided an overall analysis, such as Commoner’s, that could provide a framework and a new direction for technical and reform programs and for local actions. They also neglected the immediate needs and demands of community groups, Blacks and other minorities, the poor and the unemployed, women, and other groups not represented in the leadership of various organizations. More important still, they ignored the ability of such groups to transcend and integrate their immediate demands into a general political strategy.

Labor, community and environmental representatives all included bureaucrats and local politicians or lobbyists with little interest in concrete social change. Many people at the conference, however, were concerned not with saving the earth as it is, but with establishing real contact, understanding and alliances, because they saw that we have to change the world in order to save it. Perhaps what distinguished the environmentalists who agreed with this view from most of the other social activists in labor and community groups was a strong intellectual concern (sometimes too abstract) for general economic and political problems and solutions,. and also more typically middle-class positions, often based on scientific, technical or academic jobs.

The second part of the conference was, in fact, dominated by social activists of the three groups. They had much in common and they all attempted to reach out and organize that large section of the American people who neither identify themselves with traditional labor nor with the narrow defensive positions of the traditional middle class. There was hope—and now some evidence—that when social activists could listen to each other, without being offended, intimidated and confused by bureaucrats, academic experts and traditional politicians, they could talk together and perhaps work together later. Through a considerable amount of work and good thinking, some of the problems in the way of major radical change had been defined more clearly. Some of the contradictions between the immediate demands of the oppressed, the poor and the unemployed (or marginally employed) and the long-term needs of everyone to control our own work and community environment and our future, had been examined. A growing awareness has matured that such contradictions must be resolved among the people, rather than allowed to be magnified and used against them.

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 4 <<

- Some of the planners were: United Auto Workers, United Steelworkers, Communication Workers of America, AFL-CIO, Urban League, Citizens Action League, National Council for Senior Citizens, Nader’s Public Interest Research Group, United Church Board for Homeland Ministries, E.P.A., Environmental Action, Audubon Society, Wilderness Society, Environmentalists for Full Employment.