This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Science Teaching: The Boston Science Teaching Group

by Pat Brennan

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 8, No. 2, March 1976, p. 27-28

Getting together with a group of people who do the same type of work as you do and discussing the pros and cons of that work can be quite valuable. Doing just that has been one of the functions of the Boston Science Teaching Group of Science for the People. For the past five years a group of high school and college science teachers, students, and other interested people have met once every two weeks to share their thoughts and ideas and to plan activities aimed at mitigating some of the frustrations of teaching science in this society.

We have benefitted greatly and learned much from these discussions. One of the important things we have learned is that each of us is not aione in our frustrations and alienation. Indeed, we share common problems. For example, many of us are alienated in our work because of excessive course loads and school or curricula restrictions. We have learned that schools in general are alienating for both students and teachers and that science is almost always considered a real ‘tum-off’. We found that science is viewed as another of those subjects for which there is always a ‘right answer’ and that students after many years of exposure to this no longer have the confidence to come up with their own ideas and answers. These problems, coupled with curricula that foster noncritical thinking, make teaching in general and teaching science in particular a formidable task.

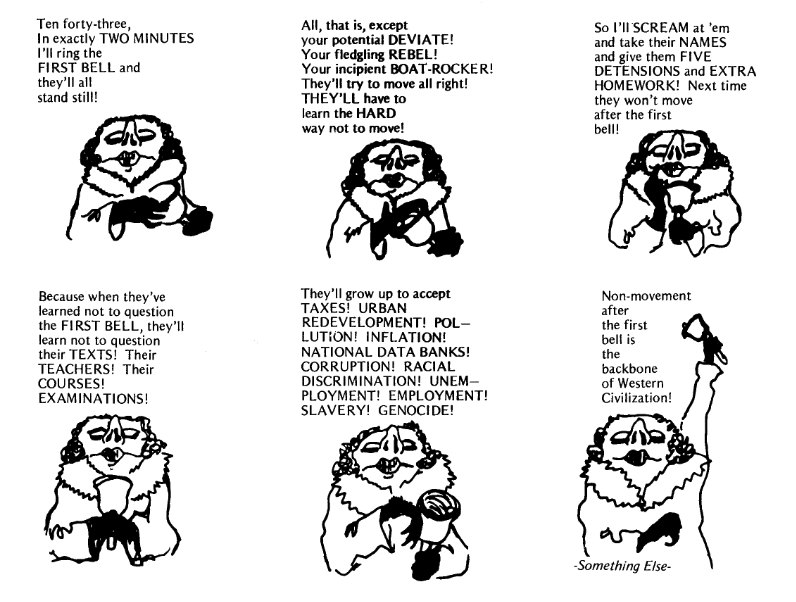

As teachers we have found ourselves in a double bind or contradiction in that we are not only a part of the educational system that functions to socialize people into this society, but we are also part of a group which wants to change both the socialization and the society. The enormity of the task is horrendous since the educational system is but a small part of the larger society, and merely reflects the larger society which it serves. The United States is a highly competitive society built around certain myths of freedom, choice, democracy and justice. The schools maintain these myths despite the fact that most people have few options and live in a state of financial insecurity and political impotence. Schools, both by their structures and curricula, reinforce the idea that most people’s poverty and alienation are the result only of their own stupidity and personal failure to achieve and not at all connected to the political or economic structure of society.

What ways have we as science teachers found to cope with these contradictions in our jobs? Besides discussion, one of the inroads we have attempted in our teaching is to bring out and make obvious to students the so-called ‘hidden curriculum’ in the materials we are studying. By the ‘hidden curriculum’ we mean the types of values or beliefs that are inherently in any curriculum material we utilize, i.e. the unspoken or sometimes omitted messages that accompany all those supposedly value-free scientific facts and concepts.

One of these values is the myth of apolitical, benevolent and all-knowing science. This myth includes the idea that the answer for all social ills would be found through scientific research, if only there was more or better funding. Problems as diverse as headache, indigestion, poor working conditions, hunger, inadequate energy supply etc. supposedly can be solved via more and better scientific research. A restructuring of society is never suggested or implied. The myth is reinforced by curriculum materials which involve only the technical aspects of a particular science and never the social, economic, political or ethical aspects of the subject. The science presented by most curricula is of the ‘pure’ or theoretical variety which relates little to the practical needs of everyday life. This tendency to dwell on the theoretical aspects of science is also used as a means of tracking students, separating them into the more elite group (those who may go on to become scientists) and the lower-echelon group who are considered unable to comprehend the complexities of such esoteric subject matter. The elite or “academic” students might never for example learn how to repair basic electrical appliances but they would become experts on electrical theory, while the non academic or slow groups never learn the theoretical basis for the operation of mechanisms they learn to repair. Often both teachers and students develop condescending and patronizing attitudes toward those who do not study theory. This is another way in which curricula and schools reinforce the social divisions and class structures that exist in our society.

Another value which permeates science curricula is the image of the scientist. In most curricula a scientist is portrayed as a very special person of prestige, status, importance, strength, honesty and brilliance. He (never she) is a person who does work that ordinary people like ourselves could never even aspire to, let alone do. Quite importantly, the scientist portrayed is almost always a white male who is often dressed in a white lab coat and wearing glasses. Given such an image, it’s not surprising that science is a tum-off for most kids.

In addition to exposing the ‘hidden curricula’ in our classrooms, we continually attempt to raise questions about the social aspects of the scientific areas we might be studying. For example, when discussing ecology, we also discuss the politics and economics of overconsumption and waste; when we study genetics we also examine the social and ethical aspects of genetic engineering and when we study nuclear power or common diseases, we examine the politics of energy and the functioning of the health-care-delivery system in the U.S. and China. An outgrowth of the need to examine the social impact of science has been the writing by the Science Teaching Group of a series of alternative curriculum materials to be used as supplements to the standard science curricula in high schools and colleges. Known as the ‘Science and Society Series,’ it consists of pamphlets on areas such as Energy, Women and Health Care, Genetic Engineering and nutrition. Most of us use these materials in our own classrooms.

Although we realize that examination of the ‘hidden curriculum’ and/or bringing to the classroom an awareness of the political and social aspects of science will not bring about the kind of fundamental changes that are needed in this society, we do see our work as a part of a larger struggle. Clearly greater changes are needed to change the way science is taught in our schools and how it is used in this society.

Being a part of a group of persons who are struggling in similar ways provides support and incentives. By working together in supportive ways during the past few years, members of the science teaching group have developed important skills and have been empowered to continue our struggles. We have also learned to work as a collective; to share responsibility for getting things done and to engage in constructive and supportive criticism within the group. We have also learned to tolerate differences and contradictions and thus continue to see ourselves as a part of a greater movement towards social change.

Pat Brennan

>> Back to Vol. 8, No. 2 <<