This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Science for the People Activities

by Multiple Authors

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 4, July 1974, p. 30 – 34

COMPUTERS FOR PEOPLE ORGANIZED IN CHICAGO

Last summer a number of us began to work as a support and education group in the area of computers. Some but not all of us were members of SESPA; we included people in math and sociology as well as computer workers.

So far, we have worked on two specific projects: development of a mailing list program for processing the mailing lists of community and movement groups; and data management for a research group that has compiled a data bank on the Chicago area power structure. The mailing list program is quite technically sophisticated: output can be in the form of printed rosters, gummed labels, and 3 x 5 cards. The list can be sorted and sub-lists can be selected from it. A variety of groups are using it (paying by cost of computer time and materials), and have learned some data processing techniques, including preparation of punched cards and a brief introduction to programming. The power structure data bank is also progressing well.

At the same time that the specific technical projects have been developed in a satisfactory manner, we have been less successful in our own organizational growth and political education. A number of personal tensions in the group have not been resolved. Therefore we were not able to integrate new people into the group. Our weekly meetings were often unproductive. In part, the most constructive way we were able to deal with the personal tensions was to avoid working together and instead to allow a high degree of division of labor in the group, with each person acting as an “expert” in a narrow field of competence. This way of dealing with personal tensions prevented us from learning new skills from each other. Ultimately these internal problems also kept us from developing other applications which we had planned, such as text editing services for groups with newspapers or newsletters, health clinic record handling, modeling of urban service systems, and short courses on programming and the politics of computing. At this point the group may split into small project oriented sub-groups.

Below is a statement of our goals; we still think the idea of a computer education and support group with the type of commitments outlined in our statement is a good one.

Why Computers For People

Science for the People means the explicit recognition of the political nature of science in this society.

Science for the People means access for all people to useful human knowledge.

Science for the People means the alliance of those who presently have access to scientific knowledge with movements for fundamental social change.

(Originally printed in New Morning) Berleley SESPA

What do we mean by “access for all people” and by “an alliance between scientific workers and social movements”? Why have we selected computer technology as a crucial area to work with people for change?

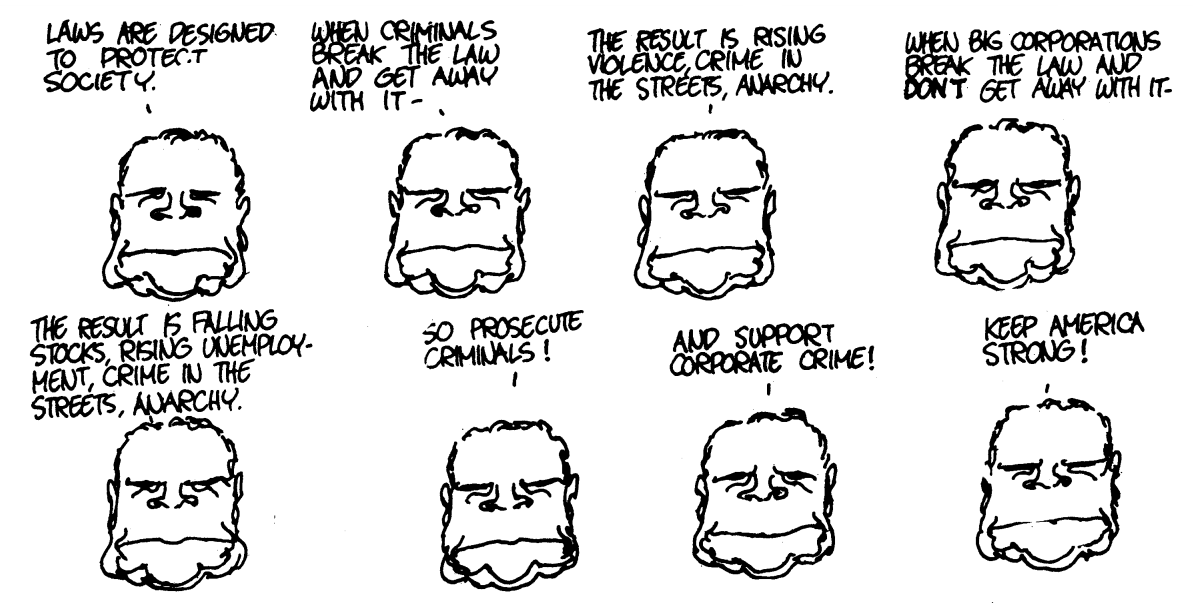

The computer field is in many ways typical of present patterns of control over technology and modern industry, but presents special problems and advantages for us. Access to computers is limited by the fact that they are expensive to buy, and maintain (at least for the time being), and can be afforded only by corporations, government agencies, universities and other rich and powerful institutions; buying time on someone else’s machine is also expensive. Few technological fields are more enveloped in a mystifying cloud of jargon than the computer field. Government agencies, credit bureaus, and other institutions deliberately act to keep people away from technology, leaving it to be used to exploit people and to maintain and extend the power of such institutions (thru data banks and similar mechanisms which are used to centralize power and harass people).

Computers differ from other technologically advanced forms of production in that they process information rather than raw materials. Thus computers, unlike oil refineries or steel mills, are potentially usable by the people in a direct way.

At the present time our ideas for an alliance are:

First, we want to teach people about computers because we are interested in this area. We want to retain our identity as scientific workers because we believe that these skills are of importance in political action and because we enjoy using them.

Second, we want to work with movement groups, and not to work for them as subservient technicians or as condescending technocrats. We are fully engaged in political struggle ourselves. This means that:

- We want to contribute to planning projects, including discussions of their political content and goals.

- Since we hope to demystify computers, we plan to teach the details of the technical operations to people with whom we are working. Ideally, our goal is to make ourselves expendable in our role as “experts”.

- We welcome the exchange of-criticism and feedback with people in the course of our work.

- We are ready to explore the political consequences of the technical procedures which we are explaining. This means that:a) We will join in examining whether computers can really help a group realize its goals-we will not assume that all technological innovation is useful.b) We will examine how the use of computers might affect a group’s organization since the introduction of computers may centralize power in the group or decentralize it, may reduce the amount of busywork that had previously played a role in the group’s division of labor, and may allow those people with access to the computer to carry out more efficient communications. We will not ignore these possible political consequences, nor subordinate them to technical details.

Third, our concept of “alliance” is expressed in an effort to build new political relations that are prototypes of those we hope to achieve in a transformed society. In this case, our alliance of politically aware technical workers with other movement groups can serve as a model for people-serving technical innovation in a new society, and as a model for roles for technical workers in such a society.

— Computers for People

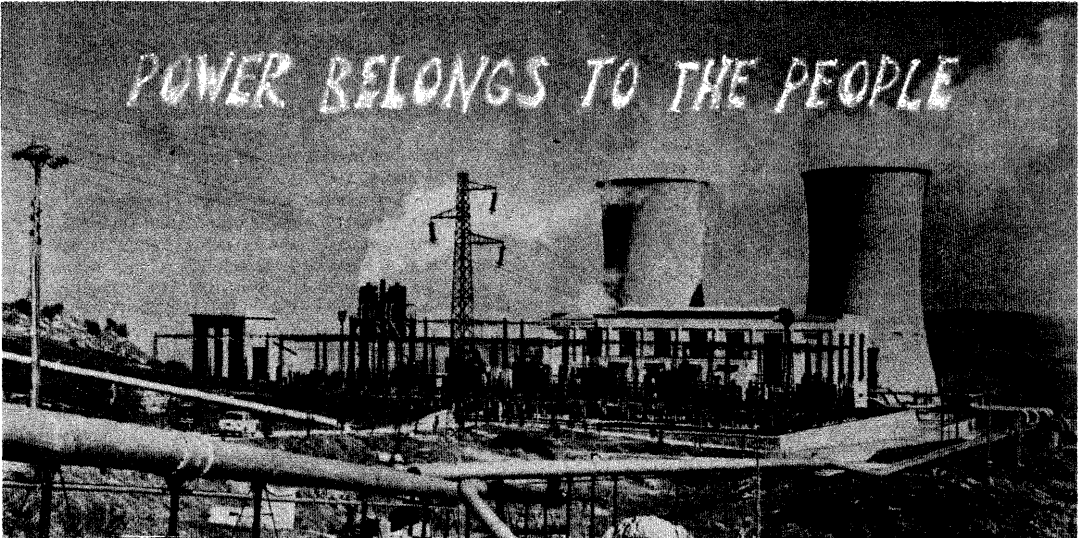

Stonybrook Science for the People organizes against Long Island Lighting Company

When the “energy crisis” hit Long Island, the misuse of science and technology was staring everyone in the face. The need for clear analysis of the economics and politics of the shortage was apparent. There were particular local issues (pressure for offshore drilling near Long Island for example) which suggested that we would, have to do our own research and writing. Our study group spent several weeks reading and discussing relevant texts and articles. We learned that the New York City group was thinking along similar lines so we got together for a discussion, but ended up deciding to write separate leaflets to fit our local conditions.

Our initial intention was to distribute the leaflet to motorists waiting in line for gasoline. We reasoned that this captive audience would be in the ideal state of mind to learn who to blame for their plight. We hoped to involve interested non-members (students and non-students) in the distribution effort. We would provide briefing sessions for the distributors and perhaps win some of them to join our Science for the People (SftP) group. As initially conceived, our “energy project” would have been exclusively an educational effort. About the time we were working on the, final draft of “Long Lines, High Prices— Who Is To Blame”, we began to think along more ambitious political lines. Perhaps an analysis of the power of the Big Oil Monopoly might create a feeling of impotence unless we could direct the readers of our leaflet to some concrete project that could demonstrate that mass movements can still win.

Our solution was to look for a local energy-related issue that we could organize around. We would hand out our “fuel crisis” leaflet together with an announcement of some meeting, demonstrations or other action that the reader could relate to—but what issue to choose?

A brief search turned up a winner. The Long Island Lighting Company (LILCO)—the local electric power monopoly—was demanding a 19% overall rate hike. (Actually more like 35% for the small user). This would be the 6th rate hike in four years! The justification was that LILCO’s stockholders were being threatened by a small decrease in their huge tax-free dividends because people had been responding to the “energy crisis” by using less electricity.

Armed with this information alone we began our publicity campaign by distributing our “fuel crisis” leaflet along with an announcement of a forthcoming Public Service Commission (PSC) hearing on the rate hike. The PSC is the N.Y. agency created by the state to give the impression that the utilities are being controlled in the public interest. It consists of five commissioners with $35,000 salaries appointed by the governor. As might be expected these “public servants” have been much more responsive to the needs of the utilities than to those of the consumer. Even when their hand-picked staff has advised against a rate increase the PSC has invariably given the utilities what they asked for.

At the hearing we met members of Citizens in Action, a group from the other end of Long Island who were also organising a movement to stop LILCO. We exchanged information and agreed to join forces in this struggle. We learned some new facts:

- Of LILCO’s 30 largest stockholders 29 are holding companies controlled by big banks.

- LILCO’s directors are also directors of the banks from whom they borrow money on short-term, high interest basis.

- LILCO benefits from a “fuel adjustment factor”. A law passed in 1908 allows N.Y. State electric utilities to purchase the fuel they need for running their generators at any price and to automatically increase the rates charged to consumers to fully offset any increases in their fuel cost. This factor alone has resulted in a 50-100% increase in electrical rates depending on usage. (We understand that similar “adjustment factors” exist in many other states.) Since the banks that own LILCO also have large interests in the oil companies it becomes clear why LILCO made no effort to shop for cheap oil-in fact, it was clearly in their interest to collude with the oil monoplies in pricing policies that result in LILCO’s fuel costs rising much more steeply than direct fuel prices paid by the average consumer.

- LILCO uses a rate structure which is based both on the amount of power consumed and the type of consumer. The people who consume less, (mostly low income persons) pay much more for each kilowatt hour than the affluent ones who consume more. Industrial users are favored with the lowest rates of all. In addition to squeezing the poor and middle income people this pricing policy encourages wasteful use of electrical power.

- LILCO has actually bribed customers with $150 bonuses to switch to electrical resistance heating. False advertising and phony estimates result in many trapped Long Island homeowners now paying more than three times what they were told they would have to pay only a few months ago! (Not to mention the ecological folly of encouraging the proliferation of inefficient all electric homes.)

With this additional information we began organizing for the next PSC hearing. This one was jammed with irate consumers. We collected names of those who would be willing to withhold part of their electric bills. The response was overwhelmingly positive and we had the benefit of our initial contact list of 300 names.

Since then the campaign has continued to grow. Our meetings, held every other week, have been attended by many people who have never considered participating in any organized movement before. At these meetings we discuss the struggle and provide educational background information on who owns LILCO and in whose interests it is managed. In general, all this has been well-received.

We have focused the campaign on three goals:

- Defeat the present LILCO rate hike request!

- Eliminate the automatic fuel adjustment factor!

- Establish a new rate structure called “life-line”, which would provide the first 300 kilowatt hours per month (minimum needs) at a very low flat rate-say $5. Larger users would pay higher rates.

Another goal, the muncipalization of LILCO has been raised and has generated some controversy in our SftP group. It has been pointed out that city-owned or cooperatively owned electric utilities in other parts of the country charge considerably less than comparable privately-owned electric companies. On the other hand it is clear that “public ownership” under capitalism usually means control and profits for the same banks and corporations that own the private electric companies. Our tentative decision on this matter is to support a municipalization effort if it develops but to take every opportunity to point out the differences between true social ownership and government ownership under capitalism.

Our principle tactic in this struggle has been to convince people, through direct contact, leaflet distribution and the public media to withhold part or all of their electric bills until our demands are met. We have attracted attention to our cause by holding a mass street rally and by picketing a LILCO stockholders meeting. (Both of these events benefitted from good local press coverage.) Our present effort is to develop local groups that can attract attention by picketing neighborhood LILCO offices, setting up information tables in shopping centers, etc.

The evaporation of the “fuel crisis” (after prices nearly doubled) has undermined our gas line distribution of our energy leaflet, but we have found that the people who are outraged about LILCO are very receptive to information linking electrical price hikes to the practices of the oil monopolies.

It is too early to judge whether we will win our struggle against LILCO. Regardless of the outcome we are convinced that our participation has been worthwhile. We certainly have been successful in making people aware of the contradictions which exist when the primary motive of management is higher profits, rather than serving people’s needs.

Also, we have learned an enormous amount about what people on Long Island are thinking, outside our academic environment. From the people who live and work on Long Island, we are learning how to distribute information, listen to suggestions, and implement action.

— Ted Goldfarb for Stonybrook SftP

Actions at NSTA Convention

The theme of the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) convention held March 15-19, 1974 in Chicago was “1984 Minus Ten and Counting”. While many of the NSTA session topics referenced values, teaching aids, futures, the future of humankind, and to a lesser extent, issues of science in society, it was clear that the NSTA wasn’t concerned about the real possibilities of 1984, ala Orwell.

Science for the People (SftP) working with the Committee Against Racism (CAR) was present for the third organized NSTA action. In contrast to the 1972 action we had a low profile at this year’s convention. We were not official program participants, and our pre-convention planning was limited in scope.

One major theme ran through all of our activities. We attempted to communicate our analysis of the social and political aspects of science in general, and specifically racism, sexism, and classism in science and science teaching. Particular emphasis was placed on discussing Jensenism and tracking in schools. This emphasis was carried out in two of our counter sessions and through literature distributed. Further, we tried to make contacts with science teachers throughout the country in order to implement a dialogue concerning the need for integrating political and economic factors in science teaching.

Activities

We distributed about 2,500 leaflets on the first and second mornings of the session outlining our activities and positions on racism, sexism, and classism. The activities we outlined included forums; monitoring exhibits for evidence of race, sex, or class bias; and attending NSTA sessions for the purpose of challenging racist, sexist, and classist presentations.

Friday evening, the first day of the conference, we met to discuss plans and draw up a schedule for staffing the literature table and attending sessions in a less random fashion than the first day. We also decided to hold an open meeting Saturday evening in order to discuss issues to raise at Sunday morning’s Issues Committee meeting. We hastily developed a leaflet and sequestered a room from NSTA the next morning.

Our Saturday evening issues meeting attracted only three non-SftP people. One teacher had come because he had seen the sexist cartoon printed in our critique of the IIS biology curriculum in “Science Teaching” issue; he was using the curriculum containing the cartoon and had never noticed it. He wanted more information on sexism, racism, and classism, etc. in science curricula. Our discussion focused on how we could expose these issues in the class and ended in the decision to present two issues to the NSTA “Issues Committee”. The first resolution called for an end to racism, sexism, and class bias in the classroom; a condemnation of racist ideology; teacher boycotts of racist, sexist, and classist textbooks; and laws prohibiting the use of IQ tests and tracking based on such testing. The second resolution asked the NSTA to open up the selection of issues and officials to voting by membership.

On Sunday morning, a number of us took part in an interesting and potentially productive experience with the NSTA issues committee. The chairperson announced that the committee was presently preparing statements on six issues: 1) women and science education, 2) accountability, 3) use of animals in classroom, 4) academic freedom and studies linking intelligence, race, and IQ tests, 5) other standardized tests and 6) science fair rules and regulations. He then broke the participants up into discussion groups headed by the committee members.

Generally, the small groups spent a great deal of the time discussing how decisions are made on NSTA stances, in general with no participation of the rank and file. The committee had been working on resolutions for several years and had a hard time getting the board of directors to approve anything. Also, the very conservative current president, Trowbridge, was about to take over what is now a very liberal issues committee, and its members expect to be removed. The 74–75 president Rutherford is very liberal while the 75–76 one, Blumenfeld, is much more conservative.

Blumenfeld, who came to one group, is trying to squelch the Issues Committee’s stand on accountability. That subject, which seems to be the latest educational concern, is being legislated in a number of states. It refers to a process whereby teachers are responsible for the success of their students. Students arc to be tested at the end of every school year and if the appropriate number fail, the teacher may be fired. Apparently, the NST A membership is overwhelmingly against this, but Blumenfeld said it was going to come anyway, so NSTA shouldn’t rock the boat.

Participation in NSTA Sessions

Our attendance and participation in the NST A sessions was sporadic and poorly planned. The following is a brief summary of the content and our participation in some of those sessions.

An open discussion on values in science education showed those science teachers attending willing to discuss topics such as science ideology, competition and other socially programmed values and owning class interests regarding science. Our participation in the session was fruitful as we were able to raise points, discuss them and develop further contacts.

Speakers in a session on career awareness and training, gave the impression that they were developing plans to channel students into job slots. These plans were presented in a social and political vacuum; however, we were able change the discussion orientation when, in a question period, one of us raised social and political issues.

Apparently, the U.S. Department of Labor is extensively funding studies of “career awareness”.

A lecture, by Francoer of Farleigh-Dickinson, on Genetics and the Future of Man (sic) contained scientific misinformation, sexist remarks and a condescending attitude toward the audience. He talked about the average intelligence in the country being lowered by poor people who breed faster than the more intelligent.

NSTA alloted only 20 minutes (fourth out of four papers inside one and one-half hours) for the one antiracism lecture by Archey Lacey of New York City University. Our presence at this very small meeting consisted of asking a few political questions and distributing leaflets.

Self Criticism

Although the negative aspects of our actions are obvious throughout the report, further discussion of several of them is necessary. Our table was in a very inconspicuous location. We should have exerted ourselves to locate the table near the registration area. In the future, this should be a priority.

SftP activities were very poorly attended, if at all. Part of this was likely due to our lack of publicity. We had no posters and no mention in the official program. In addition, our general distribution leaflets might have been too long; our leaflets were both position statements and announcements. Next year it would seem advisable to be listed in the official program and to supplement that publicity both through posters and brief leaflets. Detailed leaflets might be prepared for specific sessions. A second problem with our activities was the location of our session room; it was in an obscure section of the hotel (courtesy NSTA).

Our attendance at NSTA sessions was sporadic and mostly random. As a result of this and the small number of SftP there, we were unable to confront the real pigs, i.e. the genetics speaker and the energy panel. Next year’s plans should include research into speakers and topics beforehand so that attendance may be planned appropriately for large and small sessions.

One main criticism we received from people surveying the literature was that the literature was a negative attack on numerous problems facing this country and provided nothing constructive. It was noticed that even in our discussions at the lit. table, politics (socialism) was very low key or nonexistant; and this is the main constructive element. Further discussion is definitely needed to decide whether or not we are going to be up-front about our politics at these conferences! Another thing we neglected to do was hold discussions about politics and tactics of our actions.

Some positive aspects of our activities are that we sold a great deal of literature, particularly the Science and Society pamphlets for use in classrooms. We developed a sense of how the NST A functions in terms of taking stands on issues, and furthermore we developed a sense of some of the issues that are being pushed in education, e.g., accountability, career awareness, values, futures, etc. Certainly one of the positive aspects of our NSTA activities was the stimulating experience for those of us who had not been involved with NSTA or high school teachers. Contacts were made with science teachers from various parts of the country. In addition, the convention provided incentives for the formation of a science teaching group in Mpls/St. Paul. There are a number of issues that could be organized around with teachers, e.g., racism and sexism in text books, accountability, IQ testing, and tracking.

We invite criticisms of this report (activity) and suggestions for future planning. One suggestion we have is that those interested in planning next year’s Los Angeles conference should make themselves known early and begin planning as soon as possible.

Send suggestions and criticisms to Minneapolis SftP.

— Sandy and George of Minneapolis SftP

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 4 <<