This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

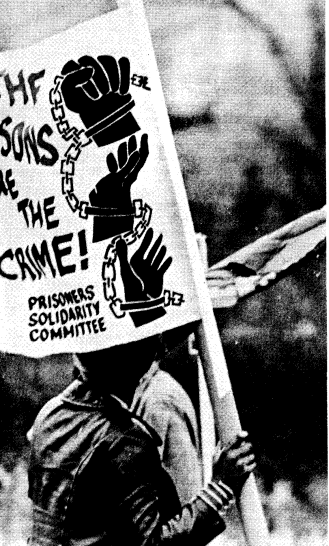

Prisoner’s Verdict: The Prisons Are the Crime

by Edward Sanchez, Charles Wise-Bey, & Christopher Dominico

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 3, May 1974, p. 22 – 25

This article is in a series of three parts, all of them written by prisoners. They have been assembled as one article, because they represent a general overview of behavior modification in prisons. The last two parts of the article have been heavily edited for space considerations.

Mind Control Units

There is presently for prisoners throughout the U.S., both state and federal, a new kind of warfare and dehumanization. For prisoners it is a present terror, for those on the outside it is a threat.

There is presently for prisoners throughout the U.S., both state and federal, a new kind of warfare and dehumanization. For prisoners it is a present terror, for those on the outside it is a threat.

At one time the old methods of “divide and conquer” were used effectively by the officials. In prisons they would sow racial tensions to keep the prisoners divided and fighting among themselves, knowing that in this state of mind the authorities had no fear of these prisoners ever becoming politically aware.

The authorities knew that through unity the prisoners could change the prisons by mass legal litigations, mass work strikes or even the complete take-over of a prison if necessary, to get justice. The officials were successful for quite a while in their tactics. I know this to be a fact, for I am a prisoner and have been for a long time, and at one time I threw all my angers and frustrations on other prisoners because of their color. And so it was with prisoners throughout the U.S.

Then awareness made its way to the prisons via music, books, papers and new prisoners from the street who had witnessed the struggle or maybe even been a part of it. As this was relayed to the prisoners, they began awakening throughout the prisons, realizing the answers to all their questions. Slowly but surely, unity of all races in prison began its long-awaited course. As evidence of this, look at all the photographs of prison uprisings. Look at the Blacks, Chicanos, Whites, Indians and Orientals standing united to death. Not too long ago you would never have seen this type of unity among prisoners. The only time they would be this close was locked in combat with each other, fighting each other to death.

When this unity came, the authorities began to change their tactics to “pacification.” This was performed by giving the submissive prisoners all kinds of little goodies such as radios, record players, popcorn, pay numbers, etc. These were given to whatever prisoners would completely submit and worry only about themselves, turning their backs completely on the great number of prisoners being beaten by the guards or thrown into little “holes” for months or even years at a time—until they committed suicide, slipped into a psychosis or made one desperate last stand for their sanity and humanity. Pacification has the same objective as “divide and conquer,” with slightly different, more perverted methods.

Now the officials have stepped up their tactics to scenes right out of a science fiction movie or book. This is the use of mind control programs, tranquilizing drugs in great quantities, electric shock treatment, and even lobotomies as punishment to non-cooperative prisoners. The objective of such sadism is two-fold, one to destroy the prisoners who refuse to voluntarily submit themselves to dehumanization, and second to scare at the same time some into submission by the horrors inflicted on others.

In October of 1973 the federal government is supposed to open the National Behavioral Research Center in Butner,1 North Carolina. By “national” it is meant that it will hold prisoners, both federal and state, from all over the country. Research means experimentation with prisoners as guinea pigs.

This crisis in prisons affects you outside as well if you are minority, conscientious, have political awareness, are active in movements towards social change out on the streets. Because the odds are, when and if you are arrested, you can very likely find yourself on the inside looking out of one of these programs. So you must, not only for us but for yourself as well, do what you can, while you can, to stop this in the bud rather than in full bloom. We know the government will do all in its power to curb the ever fast growing social revolution and awareness of the people.

— Edward Sanchez

The Untold Truth About Lorton

Lorton Reformatory is a prison that holds 1,300 prisoners. There has always been a struggle going on at Lorton, administration-wise. And although the population of Lorton is 97 percent Black, there is still racism going on from within. A ten year stay at Lorton has provided me with an inexhaustible supply of anecdotes about both staff and inmate classification and racism. I will describe in this article a few events which illustrate how classification and racism at Lorton function to the advantage of the staff, and to the disadvantage of the inmates.

Although a majority of the guards are also Black. the few White guards and White inmates are very uninhibited about expressing their prejudices. In many prisons. older convicts have a mitigating influence on any kind of conflict, because they want to do their time as quietly and pleasantly as they can. These old-timers are so few in Lorton, they don’t count. The oldest prisoner is 26, and he is three years older than the next oldest. However, the youth of the inmates, the small ratio of White guards and inmates to Black, and the individual prejudices of guards only partially explain the abnormally acute tension between classification and racism at Lorton. The high tension prevails primarily because the staff as master of policy go out of their way to foment conflict and racial strife. Their policy is a slight modification of “divide and conquer”—divide the inmates and races, and conquer the convicts.

As an example, in 1972 a fight between a guard and an inmate resulted in the killing of the guard and a fight between two White and Black inmates. The higher-ups sat down at their desks to write reports about “trouble” at Lorton. Yet, there was no “trouble” when three inmates were killed, and there has never been any show of sympathy for inmate deaths. The guard killing made the guards recognize that such events could inspire similar attacks on them in the dormitories and cell blocks. Thus they played up racist solidarity by interpreting the “real trouble” as a conflict between Black and White, instead of as a conflict between guard and prisoner. The purpose was to create enough tension between inmates, that the threat to themselves would be removed. The crew bosses’ lectures the next day performed the function of indirectly convincing prisoners that they should fight and kill each other, rather than the staff. “Classification and Racism.” The racial attacks that were successfully instigated in this way set the whole compound on edge and took the heat off the guards and bosses. Although the administrators were safe in their offices throughout the crisis, they used it as an excuse to further their policy of “divide and conquer.” Events as dramatic as guard killings occur very seldom at Lorton, but racist control of the convicts occurs on a day to day basis. It particularly occurs if you are a political prisoner.

When I say political prisoner, I mean one who is arrested because of his or her political activity or ideas, whether or not on direct political charges. The term may also be applied to a prisoner who may not have been a political activist prior to imprisonment, but who, as a result of political activity inside the prison; e.g., work stoppage, strikes, or attempting to read left-wing publications, becomes a victim of harassment, intimidations and frame-ups.

This harassment is motivated by the administration, which causes an inmate to accumulate a record of minor offenses against him. This record is then used to rationalize not giving parole. Other kinds of harassment include prolongation of prison time (which indeterminate sentencing permits), denial of early parole dates, denial of good time, and continuous solitary confinement. These policies add to the tension, and tension adds to the division of prisoners against each other. The idea behind “divide and conquer” is, that if oppressed peoples can be made to fight each other through administrative pressure, then they will have neither the time nor the energy to fight their real oppressors.

— Charles Wise-Bey

Prison Experience

My name is Christopher Dominico. My experience with behavior modification and my awareness of its uses started in the spring of 1971 at Walpole State Prison.

That year, the educational program at Walpole—what little there was—included two college-level courses through what was then called the STEP program. One of these courses was on behaviorism, and dealt mostly with B.F. Skinner and his ideas of human control. My perception of the environment I was living in began to change.

I was never one to attend counseling at the prison, but some men do. Counseling, to me, was something one did with friends and not with some paid state official. These counselors appeared harmless before my course, now their actions seemed questionable. They were helping men adapt to the prison environment. Prison is not a normal environment, people are supposed to have problems here. If the counselors help people adapt to an abnormal environment, I realized, then they must be helping them to become abnormal. It is with this awareness that I recount the following.

Walpole Prison is divided into two sections at the center of the main corridor by a control center. The control center contains the dials and switches that operate doors, intercoms and hidden microphones. The guards who adjust these dials sit behind glass windows, staring at anyone who goes by. On one side of the control center is the Maximum Security section, on the other is the Minimum section. The cell construction and the amount of administrative surveillance is the distinguishing difference between the two sections. In the Maximum section, cell doors are a grid iron electronically controlled screen. Every action of a man in one of these cells can be observed from various windows wiich face the tiers of the cells. Prisoners in the Minimum section have full metal plates, with small windows, for doors. A guard must walk to the door and look in to view the convict’s actions. Minimum section prisoners have windows at the back of their cells. Maximum section prisoners do not have windows; it’s hard to breathe.

New men coming into the prison are first housed in the Maximum section. They remain there for about eight months—and are then allowed to move their residence across the prison to the Minimum section provided there have not been disciplinary reports filed against them. These are reports on a resident’s actions which are termed administratively undisciplined, like a smoker’s cough.

In 1972, Raymond Porelle was appointed superintendent at Walpole, ” …amid unrest and turmoil” according to the Herald American. He was to be Massachusetts’ answer to the prisoners’ pleas for their civil rights. His role was to initiate changes designed to curb and manipulate prisoners’ attitudes and priorities. These changes were intended to replace the prisoners’ awareness of their violated civil rights, and their actions to remedy this situation, with a new priority—day-to-day survival.

On December 29, 1972, Raymond Porelle closed Walpole to visitors, families, friends, and all other public officials who were not members of Walpole’s immediate administrative staff. The shutdown was executed without any warning. At noon, men were locked into their cells as usual to be counted—but the doors were not opened for regular activities that day. We prisoners heard on the radio that Walpole was closed to community access because of a security shakedown.

Two days later, the shakedown started. Cell by cell, the guards proceeded around the blocks. When they opened my door, they asked me to step out of my cell, and they walked me down the tier to the shower stall. I was then stripped of my clothes, which were then searched. When I got back to my cell I found three guards tearing my things apart—books, pictures, artist supplies, family albums and personal belongings were being tossed over the tier to the block floor—already piled high with other prisoners’ possessions. It may sound funny to some, but my cell is my home and it hurt to see my belongings torn and hurled to the floor. I had lived in that cell for about three years and had grown accustomed to my family’s picture on the wall. I was left with two sheets, changes of clothes, one roll of toilet paper, one bar of soap, a tooth brush and a comb. All the men at Walpole were to go through this same process until everyone had exactly the same amount of physical possessions, which equaled the above list. Stripped bare of all my possessions, the only thing left for them to take was my life. In a way, this gave me a stronger psychological advantage. I had nothing more to lose.

Two days later, a guard told me I was being moved to the new man block, No. 8, at the Maximum section. I was accused of breaking my window. They said the disciplinary board had met and decided to move me. I was walked to block No. 8 in the custody of about twenty guards. As I was led down the main corridor, things looked strange. Groups of guards were huddled in discussion along the corridor laughing and joking. There were no other prisoners around, just me and the guards.

About two minutes after I reached my new cell, someone yelled, “Who was the guy they just brought in?” I yelled out my name. Someone started laughing and said, “They got him too.” None of us could view one another. All the cells face a wall full of windows. We could not see one another but the administration could see us.

At the time of the shakedown, I was the vice-president of Walpole’s lifer group and the chairman of the Christian Action group (non-sectarian). These were two community access groups designed to provide prisoners with an opportunity to relate to the outside world. The groups were becoming far too organized for the administration’s taste. The administration had to deal with that organization, with the groups of people who were making logical, concise proposals for change. How did they deal with it?

Block No. 8, it turned out. was filled with the key members of each community access group. It seemed that Porelle was setting up a Maximum Maximum section-security block at one end of Walpole. And suspicions mounted when they welded steel plates across the block door.

At the same time. other prisoners were being moved. Some men ended up in the Minimum-Minimum section or cadre block, which was set up on the exact opposite side of the prison to block No. 8. The cadre block was to hold an inmate “skeleton crew.” This crew included prisoners who held key positions throughout the institution. They could keep the various prison industries running, provide maintenance duties, and operate the kitchen. Basically, these men would provide enough labor to maintain the orison. which would not operate for any length of time without it.

The cadre block prisoners were allowed color t.v., cushioned chairs, important visitors and their families. We were cut off from our families, other prisoners, mail privileges, and fed in our cells on paper plates with plastic spoons. Guards would come in to feed us telling us about the cadre block. They told us that all other prisoners were allowed out of their cells and confined to block areas, allowed visits and mail. That the cadre prisoners were supplying the prison labor needed to run the prison.

For the first three weeks, we discussed what was going on in the rest of the prison, and what the administration was up to. Then, we started getting on each other’s nerves. Arguments broke out and tempers flared. Many of us had never had face to face contact. Our voices represented our lives together. Our nightly discussions about what was going on, and how we could combat our situation, tapered off.

We were asked at the noon feed one day by Deputy Corcine if we wanted visits from our families. He asked us if we were willing to wash the block floor and walls. We had been throwing the almost inedible food at them for the last month. We refused to work, and we were refused visits. Later that day, while a guard was serving food, someone asked for another cup of coffee. He was given one right in the face. The whole block went crazy, everyone started yelling and throwing things out of the cell door. A guard and convict had a shouting match. That night, they came back to the cell next to mine. I heard the metal door slide open. A guard yelled, “Come out of that room, you piece of garbage.” I broke my mirror off the wall and set it up so that I could look down the tier. I heard scuffling first, then I saw my neighbor pulled out of his cell, beaten with straps, kicked and dragged out of the block door. Every man in the block was screaming and throwing things. Sinks came off the wall, toilets were shattered in total outrage at what we had witnessed.

The guards’ actions were totally unprovoked. The beatings couldn’t have been anything but random choice. The guards filed back into the block. This time they were armed—one with a meat cleaver. Each man was taken out of his cell, walked down the tier, and out the block door. He was cursed, kicked and punched. Outside the block in the main corridor each man was stripped, ogled and searched. Then he was brought back to his cell. The cells were swept clean of debris, but the toilet facilities were broken and there was about three inches of water on the floor.

The guards fed us in knee boots for about a week. They brought our food to us dressed in rain gear. Water was everywhere. I couldn’t step away from my bed. The water wasn’t bad, but everything that could float was floating in it.

One day, I was told I had a visit. My door slid open. As I walked down the tier, everything was quiet. I felt like Judas; no one had been allowed a visit for about three months. My mother was sitting in the visiting room. She said she had been at the front door of the prison every day for two months trying to visit.

Afterwards I was walked back to block No. 8 and put in my cell. I felt like I had let everyone in the block down. Then someone yelled. “Chris, we know they’re playing games with our heads, don’t get uptight.” That night, the whole block stood at their grilled doors and yelled at the walls. We were holding a discussion on what was happening. Life had been getting bizarre. You begin questioning things. I was beginning to be afraid of who I would find in my mirror in the morning.

Things began to break a few days later. The public was in an uproar over having its state prison closed down to everyone but prison personnel. A state Senator had been denied access for a few hours. The public protest forced Porelleto open the doors to supervised public admittance. Of course, this meant closing down block No.8. All the men in block No. 8 went before a disciplinary board and were charged with various offenses. I was charged with about nine offenses ranging from the destruction of state property to verbal abuse of a guard. The population of block No. 8 was distributed to different blocks around the institution. A few days later, Porelle resigned claiming mental fatigue.

— Christopher Dominico

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 3 <<