This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Energy

by David Jhirad

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 6, No. 1, January 1974, p. 4 – 11

The following article, taken from a pamphlet published by the Boston SftP Science Teaching Group [see ad p. 23 this issue] provides a broad survey of the economics of oil and of the current energy ‘crises’. A future issue of Science for the People, focussing on the topic of energy, is now being planned. An energy group which will function in part as a magazine support group now exists in Boston. Several articles are being written by different people around the country and we want to encourage others to contribute as well. Some general areas which seem to demand attention are: 1) A discussion of the ‘blaming the consumer’ syndrome, and an analysis of the origins of our material culture which diminishes most people’s welfare through conscious mis-design. 2) Case studies of the demise of railroads and public transportation systems. Studies of building design for natural cooling and heating, alternative technologies, reactor safety, etc. 3) A critique of the Limits to Growth hypothesis. 4) A global political analysis of the energy situation, its origins, ruling class strategies for power and where we are heading.

In this forthcoming issue, we would like to go beyond descriptive analysis to proposals of political action. As pointed out at the North East Regional Conference, active political involvement should not only benefit from a magazine with ‘good material’ but it should also be the main source of such material. The sorts of ideas which may become relevant in the coming year include: 1) possible kinds of local strife as shortages in transportation, housing, fuel and heating begin to take effect, 2) reports of job-related struggles related to the energy crises (lay-offs, shut-downs, etc.).

Contributions or suggestions should be sent to the Boston SESPA office c/o Magazine Support Group—Energy.

WHO MAKES THE MAJOR DECISIONS?

At the heart of the energy industry are the giant multinational corporations. At the present time, seven international oil companies (Standard Oil of New Jersey, Texaco, California Standard, Gulf, Mobil, Shell and British Petroleum), five of them U.S. based, dominate the international oil markets, controlling ⅔ of the oil and natural gas.1 These companies are involved in the extraction, refining, marketing and transportation of oil and gas products. There is a second group of 20-30 smaller companies, referred to as the “Newcomers” or the international minors’, which are primarily U.S. firms (Standard Oil of Indiana, Phillips Petroleum, Continental Oil, Atlantic Refining, etc.), but include important firms from other countries, such as the Japanese-Arabian Oil Company and the ENI of Italy. In spite of their differences, these two groups have the same primary aim of profit maximization.

The Soviet Union also plays an important role. It has exported oil to a number of countries in Eastern Europe and Western Europe, as well as to Egypt, Cuba and Brazil. In order to break into existing markets they have to offer lower prices and the possibility of bartering other commodities for oil. In recent years, however, Soviet oil exports to the Third World have slowed considerably.

History

In recent years, the international oil industry has moved to extend its holdings over remaining portions of the globe (the Arctic, South-East Asia), and has also branched out within the North American continent to buy up reserves of coal, natural gas and Uranium. One of the factors that prompted this trend was the nationalization of the oil industry in Iran in mid 1951. At the time, the only oil company operating in Iran was Anglo-Iranian (later BP), with a 51% share owned by the British Government. Progressive forces in Iran felt that their country got little benefit from the oil industry, and that real power over their destiny and economic development could only be obtained through nationalization.

A British boycott of oil from Iran was followed in 1953 by a coup which overthrew Dr. Mossadegh, the premier, and reinstated the Shah. The role of the CIA in executing this operation has been well-documented.2 Herbert Hoover was then sent out to Iran by Eisenhower to make arrangements for Iranian oil to be controlled by a consortium of British, French, Dutch and American concerns.

This deal enraged Enrico Mattei, head of the Italian State enterprise ENI, and he attempted to break the monopoly of the Anglo-American oil cartel. Mattei proposed the idea of a joint Italian-Iranian venture with the Iranian Government getting 75% of the profits. (A 50-50 profit split was currently in operation.) The Iranian Government agreed with the proposal, and this served as an early model of participation in oil policy-making. Saudi Arabia made a similar arrangement with the Japanese, and the Mattei example was increasingly adopted by the nationalist Arabs of the Organization of Oil Exporting countries (OPEC). Standard Oil of New Jersey tried to accommodate Mattei with offers of cheap oil and refining capacity, but he was killed in a plane crash before the deal went through.

As independent and nationalist regimes in the Arab countries have increasingly seized control of oil resources through participation and shared profits, in part encouraged by the presence of the counter-vailing Soviet empire, the oil companies have been forced to diversify their holdings in two ways. They have extended their ownership over other energy sources in the U.S. to the point where they now account for over a quarter of domestic coal and Uranium production. For example, Jersey Standard now has major Uranium deposits, is fabricating nuclear fuel, and has accumulated the largest block of coal reserves in the nation (six billion tons in Southern Illinois). The Oil industry has now become the energy industry.3 They have also staked out their claim over South-East Asia and the Arctic, and are involved in drilling for oil and gas on continental shelves and sub-sea territories around the world. This consolidation of political and economic power is enhanced by the fact that the large companies are the only source of information about the size of our energy resources.

All this means that a handful of corporations have set themselves up as a “private government of energy,” and are in a position to determine the development rate and uses of the world’s remaining fossil fuel resources and alternative energy sources as well. But the energy companies are not an isolated sector of U.S. industry. Rather these companies are an integral part of the corporate system in which planning and accommodation are joint activities, the government a willing junior partner.

How the Government Helps the Energy Companies

Two themes are immediately obvious here—the first is the monopolistic nature of the oil industry (eight companies hold 64% of the nation’s crude oil reserves and are responsible for 55% of the gasoline sales). The second is that government policy has favored this growing concentration of economic power rather than acting in the best interests of the public.

In a remarkable report released in Washington on July 17, 1973, the Federal Trade Commission accused the nation’s eight largest oil companies of conspiring to monopolize the refining of petroleum products over a period of at least 23 years. The result, according to the FTC, has been a shortage of gasoline and other products in some areas of the country, when no “real” shortage exists, “substantially” higher prices forced on American consumers, closure of some independent marketers of petroleum products and “excess profits” for the eight conspiring companies. The FTC complaint recited 11 different ways in which the eight oil companies were said to have acted illegally to create and maintain a monopoly.

The government has helped the oil companies a great deal. One example is the number of tax loopholes for the industry. While the average citizen paid federal income taxes at the rate of 20% or more in 1970, the five large domestic oil companies paid an average of 5%. (Gulf paid only 1.8%).4 Further, a great deal of the U.S. oil supply lies on the outercontinental shelf, which under law is administered by the Interior department for the Federal Government. But even here the Government has turned over administration of oil production rates to the industry dominated state-regulatory commissions.

In regard to natural gas, the 1954 Supreme Court Phillips decision authorized the Federal Power Commission to regulate the price of natural gas at the well-head… For ten years, the FPC ignored the court order. The FPC finally established a pricing mechanism in the sixties. Very shortly after, the oil companies warned of an impending gas shortage, and argued that the price of gas be raised to encourage the companies to search for new supplies. It is difficult to know whether there is a genuine gas shortage since all figures on gas reserves are provided by the industry, and there is no independent government estimate. The staff of the FPC questioned the industry data, but John Nassikas, Chairman, and the other members, accepted the industry’s statistics.

The Internal Revenue Service allowed oil and mining companies to buy coal firms in the mid-sixties using pretax corporate profits, thus avoiding paying corporate income tax on the money used for the acquisition. At the same time, the Justice Department (anti-trust division) and the Congress allowed these major mergers to go forward without opposition. The result—three companies, two of them oil firm subsidiaries, control 27% of all coal production in the U.S. In the past five years, oil companies have increased their share of the national coal production from 7% to 28%.5

The connection between the Government and the international oil companies is complicated by the existence of a large domestic oil sector (companies without international holdings), and the existence of conflicts between the domestics and the internationals. In spite of this, U.S. Foreign Policy has actively promoted the interests of the international oil companies.6

Nixon’s energy message, unveiled originally in April, 1973, and modified with each change in the economic situation since then, has been exuberantly greeted as a bonanza for all sectors of the oil industry, domestic and international. The message eased restrictions on the import of oil, lifted Government controls on natural gas prices, increased support for domestic oil production and refining, and posed a serious setback for the environmental forces in the country. The only unpredictable element was a generous new system of tax credits for oil and gas exploration. The net result of all this was to drive up the already-bloated price of oil-stocks. Also, it offered little hope for an enlightened policy of clean cheap energy that could prove undamaging to the majority of people and their environment. The corporate recipients of this generosity could have written the message themselves—its language and future visions are remarkably similar to the copy produced by advertisers for the petroleum industry.

DEPLETION OF RESOURCES

The energy crisis has come to mean many things, each characterized by a different time-scale. We are apparently confronted with:

- immediate problems of supply and distribution of gasoline over the next few months,

- questions of energy production and refinery capacity over the next three years,

- difficulties in world oil production over the next 10-15 years,

- ultimate depletion of world oil supplies in about 40 years.

It is convenient to treat each of these phenomena separately.

- It is important to stress that the term “energy crisis” as promoted in thousands of corporate advertisements and government pronouncements refers to the first two time scales, and particularly the first. There is growing evidence (like the FTC report) that the short term shortages of oil, gasoline and natural gas are convenient devices for allowing the major oil companies to implement a strategy which has the following goals.

- Forcing independents out of business.

- Countering the forces of Arab Nationalism (which seek increased participation in oil operations and profits).

- Diversifying holdings both geographically (the Arctic, Indonesia, Indochina) and in terms of controlling the development of other energy sources.

- Destruction of environmental opposition to projects such as the Alaska pipeline, drilling on the outercontinental shelf, extensive strip mining in the western states and nuclear power.

- Ensuring governmental and administrative arrangements that will further lubricate responsiveness to the interests of the oil companies.

- A desire to raise prices at all levels, particularly at the level of retail and wholesale business, which has been less profitable than the production and first sale of crude oil.

Oil company profits have never been higher. However the return-on-investment in the energy industry really has been slipping in recent years and the current energy offensive is presumably intended to help reverse this situation. A Wall Street analyst sees 1973 as “one of the classic growth years for the oil companies.”7 The same analyst, quoted in Barron’s for June 18, 1973, was asked, “If I read you correctly, we’re in the throes of bona-fide energy crisis… If that’s the case, why bother with oil stocks at all?” His answer “The bleak picture I painted was not for oil company profits. It was for tighter supplies, rationing and fundamental changes which will see more and more intervention in the industry’s affairs by both producer and consumer governments. But all this can be true and rates of return on assets can go up.” Even S. David Freeman, director of the Ford Foundation Energy Policy Study, has stated, “The ‘energy crisis’ could well serve as a smokescreen for a massive exercise in picking the pocket of the American consumer to the tune of billions of dollars a year.”

- No new refineries have been built for several years. This is a process that could have occurred years ago, but the increased production could have endangered profits. It takes approximately three years to build a new refinery, so that refinery capacity is not likely to increase very much till 1976 or 1977.

- Over a ten to fifteen year period we can expect growing dependence of the U.S., Europe and Japan on oil supplies from the Middle East, further world monetary crises (caused by dollars flowing out to purchase oil from the Middle East), possible military intervention to prop up regimes that can keep the oil flowing to the world’s metropolitan centers, and much debate over what has been called ”The Oil vs. Israel problem.”8

Traditional sources of cheap and convenient oil from the U.S. and Venezuela will no longer supply the domestic demand—at the moment the U.S. imports about % of its oil, mostly from Latin America and Canada; 6% from the Middle East. It is estimated that the U.S. will be importing 60% of its oil in 1980, mostly from Middle Eastern countries. These projections could change drastically If the Government commits itself to a program of making the U.S. self-sufficient in energy.

The Wall Street Journal considers that “the flood of dollars and other Western currencies into Saudi Arabia and other Oil nations threatens to become the number I problem of the World monetary system during the next decade.” The key question is: How will the money be used? In another decade, Saudi Arabia is likely to have reserves of about $30 billion in gold and foreign exchange, double the present American total. By 1980, fuel imports are expected to cost the U.S. up to $20 billion annually, and this is being considered unacceptable by Washington.

One of the underlying issues in the current Middle East conflict is the desire of Saudi Arabia and other capital-rich oil states to securely invest these funds in the Middle East area using advanced western technology while at the same time gaining access to U.S. and world markets for the resulting exports, including oil-based products.

There have been attempts to encourage investment of this money in U.S. corporations. Another way the money has been used is for arms purchases from the U.S. and Britain. Iran, for instance, has purchased close to $3 billion worth of phantom jets, hundreds of helicopter gunships and personnel carriers, British Chieftain tanks with laser guided artillery, destroyer frigates and a fleet of hovercraft to skim battalions of assault troops over the waters of the Arabian Gulf (Persian Gulf).

This military build-up is clearly directed at any internal movement aiming for the kind of social change which would allow the people in the area full control over their oil resources. Iran’s secret police organization has been ruthless in suppressing political dissidence and the ruling groups of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Dhofar have taken similar steps to arm themselves against any threat of internal take-over.

- The references on page 11 describe the known World and U.S. resources (renewable and non-renewable) in some detail. Briefly, the situation is as follows: At present rates of consumption of energy,9 most of the world’s coal reserves will be exhausted in the next 300 years. 90% of the world inventory of oil will be used up in the next 40 years, and most of the natural gas in the next 25 years. If conventional reactor technology is continued (use of Uranium 235) the reserves are only sufficient for a 20 year supply. The use of breeder technology will extend this considerably (use of the more abundant Uranium 238) but this technology is also plagued by serious hazards that will be described later. Four other forms of energy appear to be possibilities for the future—solar energy (direct and indirect), nuclear fusion, tidal energy and geothermal power.10,11 Mastery of the processes involved in utilizing the first two sources should provide us with enough energy for a long time, with minimal environmental impact. Solar energy for large-scale use is already a technically feasible proposition 12, 13 —one might wonder why we are not making the necessary political and economic changes to make this a reality.

THE ALTERNATIVES

Which technologies get developed and which are neglected reflects the opportunities and priorities of those in power, including the energy industry. The decline of railroads and public transportation, the hypertrophy of the automobile, the wasteful reliance by aluminum producers on ‘cheap’ electricity, the extreme sophistication of oil geophysical and petrochemical technologies, the neglect of safe and non-destructive coal-mining, of combustion technology for high-sulfur coal, and of building design for natural temperature control and for energy conservation—all are consequences of high priority for private profit and low priority for the people’s optimum material well-being.

The following is a survey of alternatives variously being advanced or ignored by the energy industry and U.S. government.

The Present

The Nixon energy budget gives us a very clear idea of the priorities in energy research and development (R & D). The administration budget for fiscal 1974 (July 1973-1974) asks Congress for $772 million to support energy-related research and development, an increase of $130 million over the previous fiscal year. (There is currently a plan by the Nixon administration to spend $10 billion on energy research over a five year period). The budget demonstrates a heavy reliance on nuclear power for the production of electricity, and the nuclear breeder reactor (due in the nineteen eighties) is being pushed as the answer to the nation’s long term energy needs. In addition, the White House wants the country’s utilities to rely more on coal (as opposed to oil or natural gas) for future energy needs.14 A sum of $129 million has been allocated for fossil-fuel R&D, which includes the development of processes for the gasification and liquefaction of coal.

Coal Gasification: This was developed and used by the Germans during the 1920’s and 1930’s, and the process provided them with a supply of synthetic fue1 for the Air Force. Now that the Nixon administration has lifted controls on the price of natural gas, industrial interest in coal gasification has increased greatly in the U.S. There is expected to be an acceleration of strip-mining in the central plains and the Rocky Mountain states. In addition to the environmental damage caused by strip-mining, gasification projects will involve large amounts of water, which will be consumed and not returned after use. Since water is scarce in these regions of the country, much opposition to gasification has been expressed by environmentalists, farmers and others.15

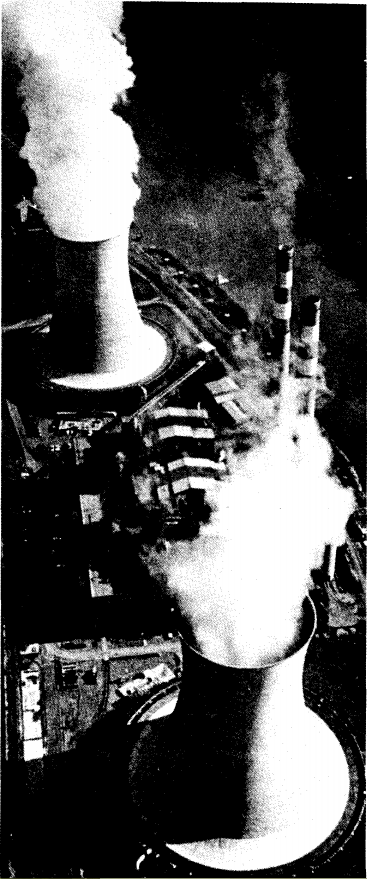

Nuclear Power & The Breeder Reactor

Since nuclear power is expected to provide about 40-50% of the Nation’s electricity in the year 2000 (up from 3% in 1972), it is important that we assess thoroughly this technology before embarking on what might prove to be a suicidal venture. (A number of good articles have been written on the hazards of nuclear power, and these are listed in the bibliography—16, 17, 18, 19.) Very briefly, there are problems associated with disposal of radioactive wastes, the possible failure of the Emergency Core Cooling System (ECCS, the device that is supposed to prevent a serious accident from occurring if the main cooling system fails), thermal and radioactive pollution. For breeder reactors there is the added hazard of handling plutonium, one of the most toxic substances known.

The most serious flaws with the current generation of reactors are the inadequacy of the ECCS and the disposal of radioactive wastes. Reactors now in operation use water as a coolant. If the water pipes should break or rupture, the reactor will still continue to generate heat from the Uranium fuel rods. Unless the emergency core cooling system begins to operate immediately (5-10 seconds), the fuel will melt through the container and large quantities of radioactivity inside the reactor could be spread over hundreds of square miles, leading to very high casualties. People hundreds of miles away could suffer genetic damage, radiation sickness and increased incidence of leukemia and cancer. The world’s oceans could be seriously contaminated for thousands of years if fission products were accidently released from one of the planned offshore nuclear plants. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) considers such an accident “extremely unlikely,” but so is an airplane accident. A test reactor near Detroit came close to this point in 1966, when the Uranium fuel source overheated and melted. The reactor was immediately shut down while scientists debated the best means to solve the problem. One of the reports commissioned by the AEC estimated that 133,000 people would have been killed in the Detroit area if there had been an explosion.

Many of the AEC’s own experts consider the criteria for an acceptable ECCS to be inadequate. The power-plant manufacturers (General Electric, Westinghouse, Babcock and Wilcox, Etc.) consider the criteria too strict. There has been a great deal of evidence to show that the AEC has consistently moved to suppress internal dissent and to ignore all information unfavorable to the reactor industry.20 Important safety programs have been cut back or terminated. The reactor manufacturers do little safety research with their own funds, and the utilities do practically nothing.21

A 1000 megawatt nuclear plant now produces a cubic yard of nuclear waste every year, wastes that have to be sealed off from our environment for thousands of years. (There have already been leakages of radioactive wastes at the AEC’s plant in Hanford, Washington.) There is currently no fully reliable way of handling these wastes, and this will have the effect of raising the radioactive level in the environment, thus causing increased genetic damage and radiation-linked diseases.

Energy Conservation

A great deal of research is presently being done on ways to reduce energy consumption, but much of the burden is being placed on individual rather than corporate consumers of energy. President Nixon, on November 9, 1973, called for householders to lower their thermostats by four degrees to help get the country through an oil-short winter. Other proposals included observing speed limits as well as more bicycling and walking. The slogan for the new campaign is ”SAVENERGY” and the symbol is a cartoon of Snoopy, the dog in the “Peanuts” comic strip, dozing on top of his dog house.

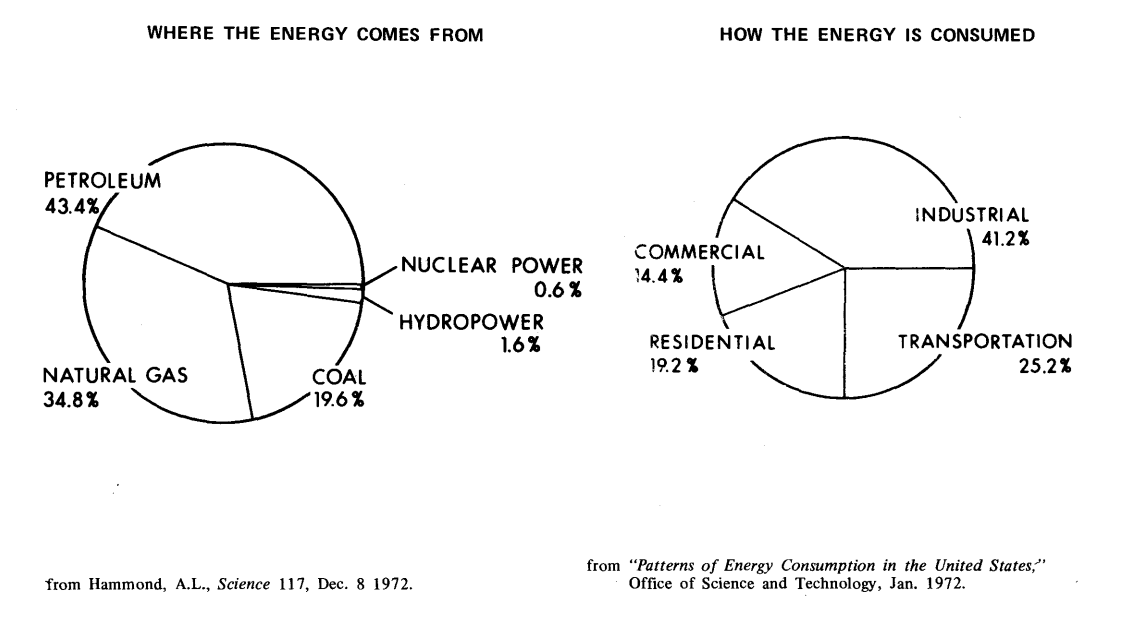

It is worthwhile to state a few facts about energy consumption in the United States. First, industry22 consumes about 41% of the total energy. The production of aluminum, steel, chemicals and paper is responsible for nearly a third of the total industrial energy. Transportation accounts of ¼ of the total energy, and cars consume over ½ of this. Approximately ½ again of the energy used by cars goes for commuting and shopping, thus pointing up once again the inadequacy of existing mass transit systems. Households consume about % of the total energy and commercial establishments about ⅐. More than ½ of the household consumption of energy goes for space heating, and this could be cut considerably through better insulation. This indicates that energy conservation measures in the home, while important, are not as significant as possible cuts in the industrial and transportation sectors.

Structural Waste of Energy

The entire structure of industrial production encourages energy waste, with its inevitable consequences for the environment.

For example, about 35 million tons of ferrous material23 is thrown away every year in the United States. Only about sixteen million tons of this is recycled. It takes about 5 times as much energy to produce steel from ore as it does from recycled material. (Comparable figures for aluminum are 30:1.) Considerable energy savings could be achieved by recycling all steel and aluminum, as well as other industrial metals, glass bottles and paper. In addition, energy expenditures on advertising, automobiles and war material could be cut substantially. Such a program would seriously undermine the ability of corporate owners to maximize profits. It could, however, form part of a strategy to satisfy majority needs for fulfilling jobs, durable products, clean energy and a safe working and living environment. This conflict of interest points up the importance of working for political structures where important decisions are taken by a majority of citizens.

The rate structure acts as an incentive to consume more energy. The cost of electricity is an example. Studies24 made in 1972 by the Fairfax County (Va.) Community Action Program show that low-income groups pay about three times as much for electricity as industry does, and more than twice as much as large residential customers. The fact is: the more you consume, the cheaper the rate. The study concludes, “This inequality persists despite the fact that costs of service in low-income areas is generally low, industrial demands for cheap power are the main reason for costly plant expansion, environmental problems and rate increase requests, and demands for expensive undergrounding of lines come from high-income residential areas rather than low-income neighborhoods.” The same rate structure applies to gas.

Short-term Energy Conservation.

The multitude of proposals for energy conservation do not tamper with this vast inefficiency and inequality. Instead, they aim for a few limited changes. But even these could save sizeable amounts of energy. For example, a report released by the Office of Emergency Preparedness in October, 1972,25 makes a study of energy conservation measures. The study indicates that improved insulation in homes, more efficient heating and cooling in buildings, limited conversion to mass transit, more efficient auto engines and increased efficiency in industrial processes could save the U.S. over seven million barrels of oil a day in 1980 (⅔ of the projected oil imports for the year). It is likely that energy conservation measures of this kind will receive a great deal of attention in the months to come, and may indeed be part of a stop-gap solution to cut down on oil imports and the outflow of dollars. Most of the structural waste is likely to remain unless we take bolder measures. Such steps might include non-polluting power plants, possibly solar, total energy systems (utilizing the waste heat from power plants—there is enough waste heat at the moment to heat every home in the U.S.), efficient mass transportation, vastly reduced automobile manufacture, drastic reduction in military expenditure and wasteful industrial processes.

The multitude of proposals for energy conservation do not tamper with this vast inefficiency and inequality. Instead, they aim for a few limited changes. But even these could save sizeable amounts of energy. For example, a report released by the Office of Emergency Preparedness in October, 1972,25 makes a study of energy conservation measures. The study indicates that improved insulation in homes, more efficient heating and cooling in buildings, limited conversion to mass transit, more efficient auto engines and increased efficiency in industrial processes could save the U.S. over seven million barrels of oil a day in 1980 (⅔ of the projected oil imports for the year). It is likely that energy conservation measures of this kind will receive a great deal of attention in the months to come, and may indeed be part of a stop-gap solution to cut down on oil imports and the outflow of dollars. Most of the structural waste is likely to remain unless we take bolder measures. Such steps might include non-polluting power plants, possibly solar, total energy systems (utilizing the waste heat from power plants—there is enough waste heat at the moment to heat every home in the U.S.), efficient mass transportation, vastly reduced automobile manufacture, drastic reduction in military expenditure and wasteful industrial processes.

Alternatives Not Receiving Much Support

The means for obtaining enormous amounts of pollution-free energy is now available. A recent report by a joint National Science Foundation-NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) panel26 asserts that solar energy is a significant national resource, and that there are no technical barriers to its widespread application. The panel feels that the large-scale uses of solar energy would have a minimal effect on the environment, and that the cost would be competitive with other fuels. It is concluded that by the year 2020 solar energy could economically provide 35% of the total building heating and cooling load, 30% of the Nation’s gaseous fuel, 10% of the liquid fuel and 20% of the electric energy requirements. The R & D budget for this comes to about $1.5 billion (present spending on solar R & D is around $8 million). There are numerous methods by which solar energy can be converted to electricity, as well as to solid, liquid and gaseous fuels. Some of these include satellite and ground-based collection systems, photosynthesis, bioconversion, winds and ocean temperature differences. Tidal and geothermal power could be supplementary sources for areas of the country where this is appropriate. Another possible area is the use of synthetic fuels, hydrogen, for example, assuming a pollution-free energy source to produce the hydrogen from the electrolysis of water.

Fusion reactors could provide us with a virtually unlimited supply of energy. We have not, however, devised a method for controlling the process that is responsible for energy release in the hydrogen bomb, sun and stars. (Optimists predict that controlled fusion will be demonstrated by 1980.) Two possible fuels, deuterium and tritium (heavy isotopes of hydrogen) are considered likely candidates. The deuterium is fused at high temperatures to form helium, releasing an enormous amount of energy in the process. (Another method uses deuterium and tritium.) Since deuterium is abundant in sea-water, we are provided with a cheap and practically inexhaustible supply of fuel. Another advantage is the impossibility of an explosive accident, and the vastly reduced waste problem. (Tritium is far less radio-active than plutonium, and easier to insulate from the environment.) Solar technology is, however, considerably in advance of fusion technology, and intensive efforts to develop the former can be expected to yield greater returns in the short run (the next 20 to 25 years).

>> Back to Vol. 6, No. 1 <<

NOTES

- James Ridgeway, The Last Play, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York,1973.

- Michael Tanzer, The Political Economy of International Oil and the Underdeveloped Countries, Beacon Press, Boston, 1969.

- James Ridgeway, The Last Play, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York,1973.

- Philip Stern, “Oil: How it Raids the Treasury,” in The Progressive, April, 1973.

- James Ridgeway, The Last Play, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York,1973.

- Michael Tanzer, The Political Economy of International Oil and the Underdeveloped Countries, Beacon Press, Boston, 1969.

- Figures available for the third quarter of 1973 indicate that Gulf Oil reported a 90% profit advance in the quarter and a 60% gain in the first nine months. Quarterly earnings gains by some other companies were: Exxon 80%, Cities Service 60%, Continental Oil 38.3%.

- At the time of writing, Oil producers in 6 Arab countries have announced a cut-back in oil shipments to the U.S. More militant factions have urged nationalization of all Arab oil if the U.S. continues to support Israel militarily and economically.

- A.L. Hammond, William D. Metz, Thomas H. Maugh II, Energy and the Future, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C., 1973.

- A.L. Hammond, William D. Metz, Thomas H. Maugh II, Energy and the Future, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C., 1973.

- Tidal energy is a renewable resource, obtained from the gravitational force of the moon. A bay that experiences tides can be dammed and the flowing water can be used to turn turbines. There is a plant in France and one in the Soviet Union. Geothermal energy is obtained from the heat within the earth, in the form of steam or hot water. 180 megawatts of electricity are produced geothermally at the geysers in northern California. These two sources are potentially much less important than solar energy or fusion power.

- A.L. Hammond, William D. Metz, Thomas H. Maugh II, Energy and the Future, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C., 1973.

- Solar Energy as a National Energy Resource, NSF/NASA Solar Energy Panel, Available from Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Maryland, December, 1972.

- The Atomic Energy Commission has just estimated the cost of a commercially attractive breeder to be $5.1 billion, up from $2.5 billion 18 months ago.

- Robert Giiette, “Western Coal: Does the Debate Follow Irreversible Commitment?”, Science, Vol.82, 456, November 2, 1973.

- Daniel F. Ford and Henry W. Kendall, “Nuclear Safety,” Environment, Vol. 14, No.7, 1972.

- Sheldon Novick, “Towards a Nuclear Power Precipice,” Environment, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1973.

- George Berg, “Hot Wastes from Nuclear Power,” Environment, Vol. 15, No.4, 1973.

- H. Peter Metzger, The Atomic Establishment, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1972.

- Robert Giiette, “Nuclear Safety: The Roots of Dissent,” A series of four articles, Science, Vol 1l77, 771; Vol. 177 ,867; Vol. 177, 970; Vol. 177, 1080, September 1, 8, 15, 22, 1973.

- In 1969, the utilities spent $323.8 million on advertising and $41 million for research and development.

- Patterns of Energy Consumption in the United States, Office of Science and Technology, Executive Office of the President, Washington, D.C. 20506, January, 1972.

- James Cannon, “Steel: The Recyclable Material,” Environment, Vol. 15, No.9, November, 1973.

- James Ridgeway, The Last Play, E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York,1973.

- The Potential for Energy Conservation, A Staff Study, Executive Office of the President, Office of Emergency Preparedness, October,1972.

- Solar Energy as a National Energy Resource, NSF/NASA Solar Energy Panel, Available from Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Maryland, December, 1972.