This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Workers Control: At the Side of the Workers

by Maurice Bazin

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 6, November 1973, p. 28 – 32

The following articles, solicited on short notice, come from two observers, holding academic positions in the U.S., who spent part or all of the past year in Chile. Both articles deal with an important component of the then advancing Chilean Revolution: workers’ control in the factories. This phenomenon resulted from two parallel and frequently joint processes: 1) moves by the government against private owners or managements which were uncooperative toward, or active saboteurs of, the government’s economic policies, and, 2) the actions of rank-and-file workers who seized factories because for them that was the concrete meaning of collective ownership of the means of production.

“Workers’ Control: Its Structure Under Allende” is based on a survey of 40 enterprises in the socialized sector. It describes the organizational changes and kinds of worker participation that developed within enterprises, often in spite of the government guidelines proposed for these situations. The article points up the difference between industrial democracy from below as was beginning to happen in Chile, and job enrichment from above as is being introduced ln the U.S. by some managements to increase output.

The second article, “At The Side of The Workers”, is a personal account by a physicist who worked alongside Chilean workers in the metallurgical factory they had seized. It presents (somewhat romantically) concrete examples of the problems that arise in developing relations between production workers and technical or professional workers. In the course of dealing with real production problems, such as the maintenance of deteriorating machinery, or interpreting design drawings, the vast potential of worker participation and control is illuminated and the technical professional discovers how much he must also learn.

These articles do not deal with the difficult problem of maintaining and defending such cooperative gains in a country where the working class is not in full control, and the embittered, money-dispossessed are actively sabotaging the revolutionary gains. The political reality is that on September 11 the global oppressors could smash, unretarded, the fruits of the people’s struggle. That setback demands that the political and organizational lessons of Chile’s struggle also be learned.

Also unanswered in these articles are questions as to the nature of the gains that were realized in the workplace. The “technical proficiency campaign” to which Maurice Bazin addresses himself is in itself a consciousness raising experience. But it is not clear from his article how the workers perceived their role in a larger struggle and whether this was a subject of discussion and political education in the factory. Clearly socialization of the factories was not complete, but to what extent was this due to the unpreparedness of the Chilean working class, or the power of foreign imperialism, or remnants of the administrative bureaucracy, and how did the workers approach these problems? Although we know that priorities of production were modified, it is not clear how or to what extent workers determined what they would produce.

We must also ask ourselves how we can contribute to this struggle? How does the scientific and technical work-force employ its revolutionary potential? Bazin engaged his commitment to the revolutionary process in the factory. Working at the side of the Chilean laborer he attempted to translate his technical learning into pragmatic tools which might advance the possibilities for real industrial democracy. By what other processes did professionals in Chile channel their skills and energy into the revolutionary tide? And the problem that presses us at home: what can be the role of the professional in factories which are not socialized, amongst a work force which is not so politically astute and hardly so organized as the forces which militated for their own liberation in Chile?

In the difficult task of uniting theory and practice, of uniting ones dream of a socialist society and a concrete daily struggle toward it, of believing in class struggle and bringing ones tangible contribution to the strength of one side, I decided to spend one sabbatical semester in a Chilean metallurgical factory, a workers-run cooperative.

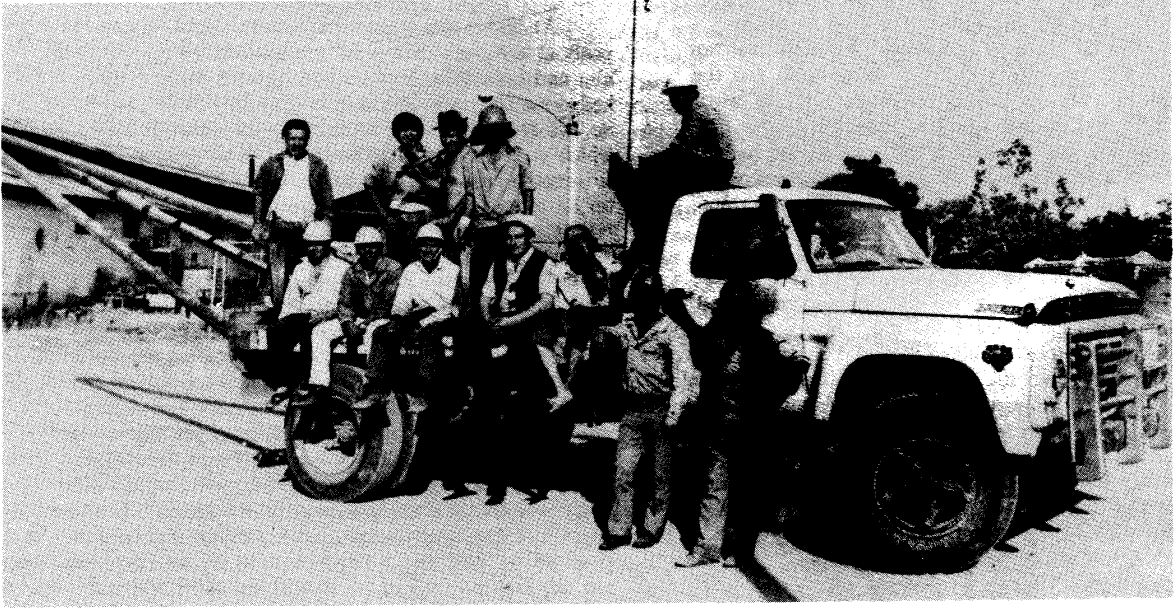

I worked regularly at the various tasks, although not the normal full ten hours. The factory is located on the outskirts of town, half an hour by bus from the center and surrounded by shantytowns. It is this large industrial area mixed with working class dwellings which has been strafed mercilessly by the Air Force and shelled by artillery since the beginning of the military coup.

The overwhelming majority of the Chilean population is made up of workers and peasants, notwithstanding the fashionable talk about the importance of the Chilean middle-class. The Chile which was struggling to take control of its own destiny starts in the many of the less-than-100-worker factories often installed in rudimentary buildings. Where I worked and taught, the factory building was a former wine storage hangar with the outside air blowing through the rafters. In winter the only heat available came from a few open fires built in metal containers by the individual work stations. It is from such factories that the idea of seizing factories from the boss originated. With it came the fundamental problem of making a factory run without some representative of the technocratic elite or, if with such representatives, the problem of keeping them under the workers’ control. It should be clear that workers cannot control their own destiny by holding formal political power alone. Especially in larger factories a workers’ council will be powerless in dealing with the bourgeois engineers who are still around, if the workers remain mystified by technology and the jargon of the educated few. To overcome that situation demands a workers’ education program which will hand over to workers those intellectual tools which allow them to judge, evaluate, and decide when technico-scientific considerations are at stake. Those attitudes which give strength to the liberal young executive must become familiar tools to members of the working class, in order to do away with any possibility of further class manipulation at the intellectual level. Such a program does not aim at making workers into better specialists in their narrow trade, although it must involve guaranteeing the knowledge of some basic skills; it aims at making workers active critical judges of their productive activity in order to modify and control it according to their own class interest. But to be able to do this, one must first overcome the attitude of “but how can I, poor laborer with no education, ever understand any of that” which the bourgeoisie spent centuries to inculcate in the minds of those whom it exploits.

My task was to be just as little of a catalyst as necessary to achieve a qualitative change in the workers’ self assurance. It is of no use to describe this practice in academic pedagogical language; its justification is ideological. It is, however, one of the very concrete things that a scientist intellectual could do to put himself at the service of the working class at the given stage of the class struggle in which Chile was.

This kind of work may be called a “technical proficiency campaign” which at the same time raises political consciousness. It has the same ideological intent as the cultural “literacy campaign” for peasants described by Paulo Freire in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed. To explain what I mean and to avoid generalities, let me give in simple diary form, examples of what I did, as I noted them down candidly after a day’s work.

February 13, 1973

The young workers who use machinery welcomed me, asking when we would have “classes.” We had agreed before to try to meet after lunch for a half hour to minimize interfering with production. All morning I had been punching holes with a young fellow on the machine which is called the guillotine. The bars we were handling were heavy and lining up the holes was unpleasant because the punch was getting old and metal barbs were staying stuck to the metal and it would not slide along easily. But how could I bring about a discussion of this problem when I knew that there is no other punch arrangement available for the machine? All the machinery in the factory is old and mistreated; the workers have to keep producing, but in so doing they degrade it even more while they hesitate to spend time to think about how to do maintenance work. How to overcome this dialectical contradiction? This is one of the most acute problems for the workers in this cooperative.

At lunch there were no more spoons for eating the soup, the tomatoes and the inevitable porotos, which are bland white beans. So I waited for another worker to finish eating to borrow his spoon; the youngest person at the table, who happened to be a student of high school age doing some practical work for the summer, offered to loan me his spoon. In the future I shall bring my own spoon from home as many workers do.

The sun was beautifully warm after lunch and one could see the Cordillera in the mist. I sat on the ground in the factory’s unfinished service building with a MIR worker, a welder, and we were joined by the only trained electrician in the factory who just came back from taking an exam to enter some more advanced course in INACAP (the state-run workers’ technical training center). He was rather nervous because 50 people were applying and only 20 will be admitted. He mentioned that after completing this course he would like to take the pre-university course and then go to the university to obtain what he called more advanced knowledge. We talked about the need to form engineer-type persons out of the working class but also of the fact that the present university will only shape elites and that one would automatically be taken out of the working class into a bourgeois frame of mind by being trained in Boeninger’s university (Boeninger was the reactionary Christian Democrat rector of the University of Chile). We discussed the fact that of the 20 students admitted, only 10 would obtain the diploma because the Communist Party, which dominates INACAP, believes in the traditional, competetive training of students.

As I walked back into the work area, the young people who man the machines announced that we should get together al trio (as fast as a shot) and not ask the shop supervisor to be with us. So we sat down on the floor of the office, got a batch of wrenches and bolts, and started talking about how one picks out a wrench to fit a given bolt. The fact that using an adjustable wrench is not good practice especially when one does not adjust the wrench tightly (which is never done by the men I work with) was a heated subject of discussion among the companeros (name used to address one another, meaning “comrades” and now banned by the military). But they were still looking for a recipe for “how to use wrenches” from an all-knowing gringo man. I wanted them to stick to that which they had discovered by themselves. So I finally pointed out that the only concrete thing that we had learned together after one hour of discussion was that wrenches can be metric or in inches and that one has to take a good first guess to select a wrench and then zero in using the knowledge that there exists a metric wrench every millimeter in size. My companeros had never been told (or better no one had ever given them a break to let them discover) how English measures work with the idea of dividing by two; no one had ever helped them stop and look at the two scales which appear on a caliper, one in inches graduated in 1/16 in. and the other graduated in millimeters. So we kept discussing how to measure bolts and ended up learning, rather conventionally, how to use the caliper. After 20 minutes, 4 out of 6 workers could make measurements to one tenth of a millimeter, but 2 still could not accept the position of the zero of the scale. But then, how do you proceed with people who have never heard of a fraction, to talk about a wrench of 5/16 inch? You just let them ask, since they will not abandon the struggle now. And I was the one who had to end the meeting and mention the word production. So we measured a few bolt heads on the guillotine and then measured again and again until 4 p.m. the position of the holes which we were making with the punch.

At that time the group of mechanical workers, roughly 10 of them, got together because an experienced worker wanted to bring up the problem of wasted efforts and material in the production and had a solution to propose. The main trigger for the discussion was the fact that more than one hundred cable hooks had been manufactured recently but they were not acceptable. Each hook is made by bending over in the forge a long strip of metal with a hole drilled at each end; the holes had been drilled so much out of place that they did not overlap enough after the piece had been bent over to let a bolt pass through them. The worker pointed out the cost of the lost metal and also the work done. His solution to the situation was to propose to hire a new chief steward who, in his words, would be able to tell everyone how to do things correctly and supervise everyone and every step of the fabrication. It took a lot of questioning on my part and on the part of the MIR worker who was chairing the meeting to bring to light other means of keeping control over the production. And the discussion broadened to consider how to improve the possibility of control by the workers themselves. Why did the companero who sweats his life away at the galvanization bath ignore the fact that the piece looked so bad and crooked and proceed to spend hours of wasted effort? Why did no one know that a bolt had to go through this restricted hole? Why, in fact, did the worker who was presenting the problem to us today not act and talk earlier? And why would anyone be so sloppy as to drill holes half a centimeter off in a piece which is 5 em. wide? The man who had initiated the discussion came back to his request for hiring a qualified supervisor but then went on to remark that all he knew he had learned at work from other companeros. Then someone mentioned that everyone should know how to use the caliper; and tomorrow I’ll sit with them again and cut up an inch into 16 pieces and somehow get at the fact that 7/8 and 14/16 are the same thing.

Friday, March 16, 1973

Every day at the side of the working class is exhilerating. I always come across the concrete proof of the fact that those who are manning the means of production are the progressive elements of the society.

Yesterday the companero who dips the metallic pieces into hydrochloric acid for galvanization told me how they modified the galvanization process because the standard procedures which I had just read about in a booklet of the Association of American Galvanizers were too time-consuming, required too much personnel, and did not give good results anyway. So instead of using a bath of degreaser followed by a bath of sulfuric acid, followed by a wash followed by a bath of fundante, a saturated gooey mix of zinc in pure hydrochloric acid, followed by the molten zinc bath at a temperature which, the manual says, must be maintained at 450 degrees within less than 10 degrees, today they use only a bath of hydrochloric acid at 25%, dry the pieces and spray them roughly with “salt of ammonia” and dip them in the molten zinc which is kept at the right temperature by looking at the color of the pieces which come out and opening more or less the fuel valve at the entrance of the heater.

Those that saved work for themselves in this fashion and made a process 30% cheaper, do not know how to do divisions or fractions; but somehow they overruled those technical dictates which generations of diligently educated petty bourgeois have accepted as sacred.

This day started out with my going early to Quimantu’s docurrtentation center (the national publishing house whose publications are now banned) to find out what CONICYT (National Council on Science and Technology) is really doing; it seems to be a mix, with all the fellowships controlled in fact by cultural imperialism but also with a few signs of progressive attitudes. On the one hand, all the papers presented at last year’s congress were just empty verbiage; on the other hand, the last issue of the weekly CONICYT newsletter announced the creation of a national prize for research and discoveries which consists however of two prizes, one for usual academic investigations, the other for technical discoveries made by workers in their factory.

As I walked along the river Mapocho towards the bus stop to go to the factory, it blew my mind to think that the galvanization process used by my companeros might get the first national prize. And I recalled the evening before, as I came out of the weekly general meeting at the factory, when one of the older leaders started telling me about their struggle four years ago in the days of President Frei; he had informed me that this group had been the originator of the movement of tomas (seizing factories). None of them still has a copy of the booklet which they had put out then to distribute to other factory workers and to trade unions. They simply initiated a new step in the class struggle; they lived it; they suffered through it; and now they go on without special pride or any evidence of looking for fame. They do not tell their story easily to political tourists who come around with uniforms of leftist journalists to visit the factory. But in the dusty yard of the factory I did not feel any romanticism either; I had worked hard with my gloved hands too many hours to romanticize proletarian life; it was much too real to be reified in any way.

So I was once again on my way to the industrial suburbs. Upon arriving, I intended to teach to a new group of six workers, those who are building the protective tubes for the support cables of the telephone poles; but my intention was put aside when one of the six, who is in charge of soldering the long seam of these tubes, asked me to help him find a better way to hold the tube closed up while welding it. The tubes were over two meters long, and clamping them little by little along their length to put the 35 welding spots required more than one hour per tube. Since there are 450 tubes to make now and more than 1000 later, he had come to the decision that it was worth putting together some piece of apparatus which would work more efficiently. But he felt very unsure of himself at the idea of having to invent, and I felt very unsure of myself confronted with the reality of the factory where only delivering something which works immediately for the production counted. Our only tools were crude: the welding machine, hammers, vises and all kinds of pieces of iron in the back storage area. We set to work, picking up angle irons, deciding to link them together, inventing a hinge by welding pieces of tubing along the edge of the angle irons and sticking a rod through it all; and a something started taking shape. We then took two vises from work tables and set them up onto the welding area table; but our cumbersome hinged gutter-like contraption would not stay inside the vises and it kept turning on its side. Moreover, handling it was difficult, because the two of us could barely lift it. Finally, my companion said we should attach guides to the vises so that our contraption would not move. Thus as the day was ending and the bell had already rung, we welded on some more guiding pieces. How I knew where to set the vises along the tube holder to spread out the compression was hard to discuss, and my companion forced me just to do it, saying that I could always explain some other time. Here were again the beautiful contradictions, this time between the necessity of getting my companero to reason by himself and make decisions on his own and the requirements of immediate achievement for production. But the resolution of this dialectical situation was evident to both of us without mentioning Engels, because, as we finally closed down the vises and brought the lips of the tube to touch, ready to weld all along in one sweep, the seam was not straight; it went slightly in a helix. Here again was the ideological necessity of linking our work with the work of the other companeros who had shaped the tube before us and had not carefully lined it up in the molding press. It is with them that we shall discuss what we built today and why their own work too must be well done. We shall educate them in technical matters just as we were educating ourselves in the practice of production work. Neither I nor my companero could have devised alone what we finally built together; we controlled and r reinforced what each thought and did. And our best moment came as we finally walked out of the factory with the sun all red behind the chimneys of other San Miguel factories, and my companero said: “Todos los otros dias hemos producido, pero hoy dia ademas hemos creado” (all other days we have been producing, but today we also created) and we took a soft drink at the little stand alongside the dusty soccer field, between the shantytown where the Socialist Party and MIR flags fly side by side and the wall on which was painted the slogan “Avansar: Ia canasta popular” (let us go forward with direct food distribution).

When someone called me up that evening to ask me to teach a course in group theory [an abstract mathematical theory] at the University, I simply said: “I can’t.”

Monday, June 18, 1973.

Talked with the new accountant, a former student who became worker, then student again and is now back at the factory after graduating. Together, we figured out the cost of galvanization which he could not reconstruct alone. We used my old notes when I was having the companeros describe to me what the galvanization work was, in order to have them do some calculations. Later he got together all the companeros who work on galvanization and had them discuss the pricing of various pieces.

Wednesday, July 4, 1973.

At lunch a companero who works making cement posts at the back of the factory yard asked me to teach him and his fellow workers how to read blueprints, as I had done with the companeros who work with machinery. So, we stood in the open air, near the concrete mixer on which a companero kept banging with a wooden cudgel to prevent the mixture from sticking. We had opened up on a wooden table the blueprint of the 10 meter reinforced cement posts. A companero asked immediately: “How can I find the size of this indented area which is drawn out here but has no dimension written along it?” We would need to find the place on the drawing where the scale was indicated; but the idea of scale, the very convention of representing an object by a scaled down drawing were new ideas. So we looked for Escala 1:5 on the general drawing and the detailed cross sections, respectively. We started measuring on paper the size of the cross section of the post (it was 3 cm. wide) with difficulty, counting centimeters one by one on the measuring tape that I alone possessed in the group. Three centimeters is too small to be the true width of a cement post; so we discussed on and on why the size drawn was not the real one; I had to offer some direct hints because time was passing quickly; we cannot be perfect all the time and go through the full “discovery” process. Then someone saw the numbers 1:5. He moved on it: “The real size must be five times larger, five times.” “That means which size?” “That means 25 centimeters,” said one companero. “No, five times larger than three does not give 25,” said another. “It gives what?” I asked. “It gives like 10 or a little more.” So I said: “Wait a minute! Five times one, that gives—five. Five times two; sorry, two times five, that makes—ten. And three times five, that makes—fifteen.” And in the silence that followed, as the sun reddened behind the polluted afternoon mist and the cold from the fresh snow on the Cordillera made our heads come down between our shoulders, one of the companeros smiled and his face relaxed as he said, weighing each word: “So that is what we can use the multiplication table for.” And the wind stung my eyes as they slowly filled with tears, having been involved in an act of “conscientization,” of biting the pear of power over knowledge.

Forty years ago my companeros had chanted dutifully mathematical litanies on elementary school benches. Since then one had worked filling pisco liquor bottles in a privately owned factory, then had been fired for falling asleep on the toilet after inhaling alcohol vapor and licking too many overflowing drops. They all had come to work here, straightening out the spools of iron wire for the reinforced concrete with an antiquated winch. They “knew” their tables of multiplication to satisfy the standard educational system. But, somehow, that system never bothered to give them the power to make real use of the stored up “knowledge”. Today, however, they felt freer, in their cooperative; free also to catch the pnermonia which their underfed bodies could not resist. At noon we had a noodle soup with three tiny cubes of tough meat and a dish of mixed vegetables. I had kept in my pocket half of my ration of bread, to eat at the four o’clock break when the welders would offer me in a tin can with a welded-on handle some hot milk prepared for them to fight the bad effects of emanations from arc welding.

We walked over to the metal moulds in which the posts get manufactured. We measured the width of the pole at mid height; it was 15 centimeters. To get to predicting the size of the indented area which we were interested ip at the beginning was just one small step away. By now, reading the tape measure and multiplying by five was a surmountable task. We did it. In passing, we discussed the purpose of the indentation, namely, to economize cement without affecting seriously the strength of the post.

By then the mixer was ready for a new batch; we poured it out into the open mould.

This article is dedicated to the Chilean workers who taught me more than I could ever offer them in return and who always welcomed me strictly on the basis of my deeds. It is also dedicated to Amalia Pando, Bolivian, 19 years old, textile worker, member of the Socialist Party, missing since Sept. 11th, and to the memory of Newton da Silva, Brazilian, member of M.I.R., killed at age 22 by early fascist shots in the streets of Santiago.

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 6 <<