This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

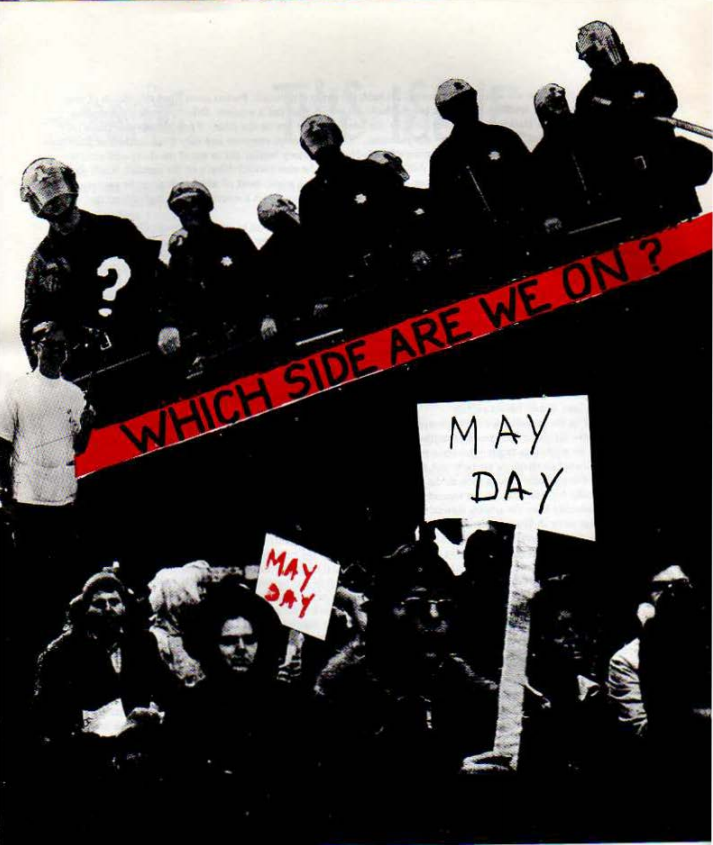

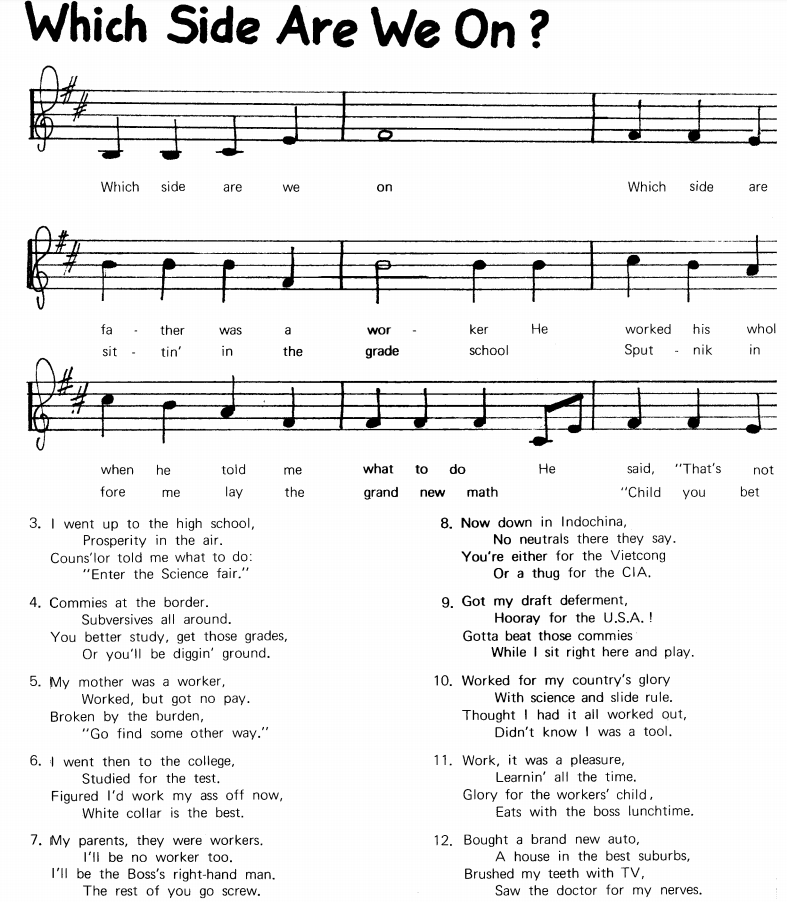

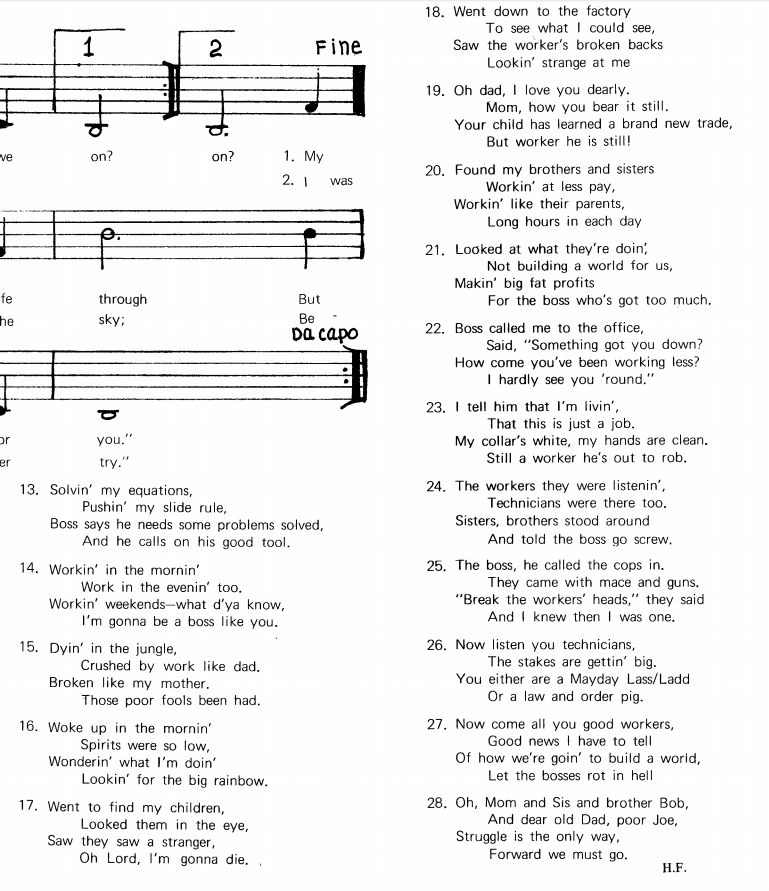

Which Side Are We On — A Forum on the Class Position of Technologists

by Jeff Schevitz, Mike Hales, Joe Neal, Stonybrook SESPA, Britta Fischer, Mary Lesser, Al Weinrub, & Andre Gorz

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 3, May 1973, p. 4 – 29

In the following pages we present, for the first time in Science for the People, a forum—a group of articles and commentaries that are directed to the same question. That question is, “What is the class position of technical workers (technicians, computer programmers, scientists, engineers, etc.) and what is their social, economic, and political function?” That we find it necessary to have two clauses in the question is itself part of the basis for the discussion. A determination of class must include not only status with respect to property relations but also other aspects of social existence.1 For example, the fact that tactical police are propertyless wage workers (most often of traditional working class origin) does little to mitigate against their objective function as the violent instruments of class rule by the very class that underpays, exploits, and abuses them. Neither can a simple formula about who directly produces surplus value provide an unambiguous class distinction.2 Thus, in short, class analysis of technical workers (ourselves) must transcend the description of us as propertyless wage workers and requires careful consideration of our role in maintaining the system—in particular, in determining to what extent we (as technical workers) are important and necessary instruments in maintaining capitalist class rule.

The origin of this forum should be of interest to our readers. SESPA/Science for the People stimulates the formation of, and provides support to, workplace study/action groups. In the course of their study, one such group of technical workers (at a technical firm in the Boston area) got into an intensive discussion over their own roles. Should we consider our capabilities as advanced technical workers to be a productive force that is “fettered”3 by the present property relations? Some argued that we were not even familiar with (let alone trained or experienced in) the technical tasks needed in a socialist society—that we were, as presently trained, a cancerous product of capitalism. Their position questioned our fundamental political outlook—that as technical workers we should emphasize and assert our identity with all workers; that objectively we are working class, the problem being to develop that consciousness among our colleagues.

In the course of the (several-meeting-long) discussion, Gorz’ article was introduced.4 It helped to focus and raise the level of the discussion. It was passed along to other SESPA/SftP people. Most were critical of the article, but found it relevant and provocative. Since it raised such fundamental questions, it seemed certain to be a firm basis for a forum.

Gorz begins with a critical look at what he calls “simplistic views” that he describes as “traditionally assumed by most Marxists”. Since a few of our correspondents seem to hold this against him, we would like to endorse Gorz’ irreverence as being in the best Marxist tradition.

Orthodox Marxism, therefore, does not imply the uncritical acceptance of the results of Marx’ investigations. It is not the “belief” in this or that thesis, nor the exegesis of a “sacred” book. On the contrary, orthodoxy refers exclusively to method.5

That is why we find some of the other articles so useful—they derive their analyses from concrete experience, without the self-justifying ideology so common in engineers’ self-descriptions. Some articles rely on extensive interviews, others on specific examples of abuses in factory situations. There are accounts of personal work experience in which the hierarchical structure itself is oppressive. The role of university academics is questioned by comrades in that situation. The ambiguous nature of the class role of technical intelligentsia is stressed, both in terms of how they should be treated by the left, and also in terms of their need (especially in groups like SESPA) to develop a coherent political line.

Revolutions are not brought about by ambiguous people. On the other hand, those who recognize their ambiguous situation do not respond to propaganda which denies that ambiguity. It seems, therefore, that our primary tasks are:

(1) to develop cadre whose subjective class position is unambiguous

(2) develop strategies to sharpen class conflict at the workplace and hence remove the source of the ambiguity.

In the last analysis (the revolution) one can only be on one side. Then, we will have to know which side we are on.

TECHNICAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE CAPITALIST DIVISION OF LABOR

Up to recent years, it was traditionally assumed by most Marxists that the development of productive forces was something intrinsic and intrinsically positive. Most Marxists held the view that capitalism, as it matured, was producing a material base which could be taken over by a socialist society and upon which socialism could be built. It was widely held that the higher the development of productive forces, the easier the building of socialism would be. Such productive forces as technology, science, human skills and knowledge, and abundant dead labor were considered assets that would greatly facilitate the transition to socialism.

These views were based somewhat mechanically upon the Marxian thesis regarding the deepening contradiction between productive forces on the one hand, and social relations of production on the other hand. Most orthodox communist parties clung to the view that capitalist relations of production were stifling the development of productive forces and that socialism, by tearing down the so-called superstructure of the capitalist state and of capitalist social relations, could set free at one blow a tremendous potential for socio-economic development and growth.

This view still pervades the political attitude of the Western European communist parties. They usually consider all available productive capacity, all available manual, technical, professional and intellectual skills as forces that will be valuable and useful during the transition period: socialism, so the story goes, will be capable of putting them to good social uses and of rewarding their labor, whereas capitalism either misuses them or puts them to no use at all.

I shall try to illustrate that these simplistic views no longer hold true. We can no longer assume that it is the productive forces which shape the relations of production. Nor can we any longer assume that the autonomy of productive forces is sufficient for them to enter spontaneously into contradiction with the capitalist relations of production. On the contrary, developments during the last two decades rather lead to the conclusion that the productive forces are shaped by the capitalist relations of production and that the imprint of the latter upon the first is so deep that any attempt to change the relations of production will be doomed unless a radical change is made in the very nature of the productive forces, and not only in the way in which and in the purpose for which they are used.

This aspect is by no means irrelevant to the topic of “technical intelligence” dealt with here. It is, on the contrary, a central aspect. In my view, we shall not succeed in locating technical and scientific labor within the class structure of advanced capitalist society unless we start by analyzing what functions technical and scientific labor perform in the process of capital accumulation and in the process of reproducing capitalist social relations. The question as to whether technicians, engineers, research workers and the like belong to the middle class or to the working class must be made to depend upon the following questions:

- (a) Is their function required by the process of material production as such, or (b) by capital’s concern for ruling and for controlling the productive process and the work process from above?

- (a) Is their function required by the concern for the greatest possible efficiency in production technology or (b) does the concern for efficient production technology come second only to the concern for “social technology”, i.e., for keeping the labor force disciplined, hierarchically regimented and divided?

- (a) Is the present definition of technical skill and knowledge primarily required by the technical division of labor and thereby based upon scientific and ideologically neutral data or (b) is the definition of technical skill and knowledge primarily social and ideological, as an outgrowth of the social division of labor?

Let us try to examine these questions. And to begin with, let us focus attention on the supposedly most creative and most sought after area of employment by asking ourselves: what is the economic purpose of the quickening pace of technological innovation which, in tum, calls for an increasing proportion of technical and scientific labor in the fields of research and development?

We may consider that up to the early 1930s, the main purpose of technological innovation was to reduce production costs. Innovation aimed at saving labor, at substituting dead labor for living labor, at producing the same volume of goods with a decreasing quantity of social labor. This prioity of labor-saving innovation was an intrinsic and classical consequence of competitive capitalism. As a result, most innovation was concentrated in the capital goods sector.

But this type of innovation, while keeping a decisive importance, has been overshadowed from the early 1950s onwards by innovation in the consumer goods sector. The reason for this shift is quite clear: sooner or later, increasing productivity will meet an external limit, which is the limit of the market. If the market demand becomes saturated for a given mix of consumer goods, the wider reproduction of capital tends to grind to a halt and the rate of profit to fall. If innovation were to remain concentrated mainly on capital goods, the outlets for consumer goods production could be made to grow only by lowering prices. But falling prices would slow down the cycle of capital reproduction and rob monopolies of new and profitable opportunities for capital investment.

The main problem for monopolies in a virtually saturated market is therefore no longer to expand their production capacities and to increase productivity; their main problem is to prevent the saturation of the market and to engineer an on-going or, if possible, an expanding demand for the very type of commodities which they can manufacture at maximum profit. There is only one way to reach this result: constant innovation in the field of consumer goods, whereby commodities for which the market is near the saturation point are constantly made obsolete and replaced by new, different, more sophisticated products serving the same use. The main function of research is therefore to accelerate the obsolescence and replacement of commodities, i.e., of consumer as well as capital goods, so as to accelerate the cycle of reproduction of capital and to create profitable investment opportunities for a growing mass of profits. In one word: the main purpose of research and innovation is to create new opportunities for profitable capital investment.

As a consequence, monopolist growth and the growth of the GNP no longer aim at or result in improved living conditions for the masses. In North America and tendentially in Western Europe, growth no longer rests on increasing physical quantities of available goods, but, to an ever larger extent, on substitution of simpler goods by more elaborate and costly goods whose use value is no greater—it may well be smaller.

This type of growth is obviously incapable of eliminating poverty and of securing the satisfaction of social and cultural needs; it rather produces new types of poverty due to environmental and urban degradation and to increasingly acute shortages in the fields of health, hygiene, and sanitation, to overcrowding, etc.

The point I am driving at is that the type of productive forms which we have at hand, and more specifically the type of technical and scientific knowledge, competence, and personnel, is to a large extent functional only to the particular orientation and priorities of monopolist growth. To a large extent, this type of technical and scientific personnel would be of little use in a society bent on meeting the more basic social and cultural needs of the masses. They would be of little use because their type of knowledge is hardly relevant to what would be needed to improve the quality of life and to help the masses to take their destiny in their own hands. E.g., technical and scientific workers, though they may know a lot about the technicalities of their specialized fields, know very little nowadays about the ways to make the work process more pleasant and self-fulfilling for the workers; they know very little about what is called “ergonomy”—the science of saving effort and avoiding fatigue—and they are not prepared to help workers into self-organizing the work process and into adjusting production technology to their physical and psychic needs. (Moreoever, they are not generally capable of conveying their specialized knowledge to workers holding less or different training and of sharing it with them.) In other words, technical and scientific knowledge is not only to a large extent disconnected from the needs and the life of the masses; it is also culturally and semantically disconnected from general comprehensive culture and common language. Each field of technology and science is a typical sub-culture, narrowly specialized in its relevance, generally esoteric in its language and thereby divorced from any comprehensive cultural concept. It is quite striking that though a large majority of intellectual workers are engaged in technical and scientific work, we do not have one scientific and technical culture, but a great number of fragmentary sub-cultures, each of which is bent on devising technical solutions to technical problems, and none of which is qualified to put its specialized concern into a broader perspective and to consider its general human, social, and civilizational consequences. Hence this paradox that the main intellectual activity of advanced industrial societies should remain sterile as regards the development of comprehensive popular culture. The professionals of science and technology, and more specifically of research and development, must be seen as a kind of new mandarins whose professional pride and involvement in the particular fields of their activity is of little relevance to the welfare and the needs of the community and of humanity generally: most of their work is being done on problems that are neither the most vital nor the most interesting as regards the well-being and happiness of the people. Whether in architecture, medicine, biology, or physics, chemistry, technology, etc., you can’t make a successful career unless you put the interest of capital (of the company or corporation or the State) before the interest of the people and are not too concerned about the purposes which the “advancement of Science and Technology” is to serve. The so-called concern about Science and Technology per se—the belief that they are value free and politically neutral, and that their “advancement” is a good and desirable thing because knowledge can always be put to good uses, even if it is not, presumably—is nothing but an ideology of self-justification which tries to hide the subservience of science and technology—in their priorities, their language, and their utilization—to the demands of capitalist institutions and domination. This fact, of course, should not surprise us: technical and scientific culture remains fragmented and divorced from the life and the overall culture of the people because the object to which it relates, that is, the means and processes of production, is itself alienated from the people. In a society where the means and processes of production are estranged from the people and erected to the status of die Sache selbst, in such a society it is not astonishing that the knowledge about the means and processes of production should be an estranged knowledge, a knowledge as reified (versachlicht) as its object itself, a knowledge that forbids, through its narrow concern for a particular aspect of die Sache, a comprehensive understanding of what everything is about (worum es im Gesamten geht).

Technical and scientific culture and competence thus clearly bear the mark of a social division of labor which denies to all workers, including the intellectual ones, the insight into the system’s functioning and overall purposes, so as to keep decision-making divorced from productive work, conception divorced from execution, and responsibility for producing knowledge divorced from responsibility for the uses knowledge will be put to.

But however estranged technical and scientific workers may be from the process of production, and however significant their role in producing surplus value or, at least, the conditions and opportunities for profitable investment, this stratum of workers cannot be immediately assimilated to the working class, that is, to the class of productive workers. Before making such an assimilation—and before speaking apropos the technical worker of a “new working class”—we have to distinguish

- situations where plants are run by an overwhelming majority of technicians doing repetitive or routine work and holding no authority or hierarchical privilege over production workers; and

- situations where technical workers supervise, organize, control and command groups of production workers who whatever their skills, are credited with inferior knowledge, competence, and status within the industrial hierarchy.

A great number of misunderstandings have arisen owing to the fact that sociologists like Serge Mallet have focused attention on situation a), whereas situation b) is, for the moment and for the near future, still much more widespread and sociologically relevant, at least in Europe. I shall therefore start by examining situation b) and comment later on the ambiguity of the technical workers’ protest movement, a movement which can hardly be understood unless it is related to the ongoing transition from situation b) to situation a).

II.

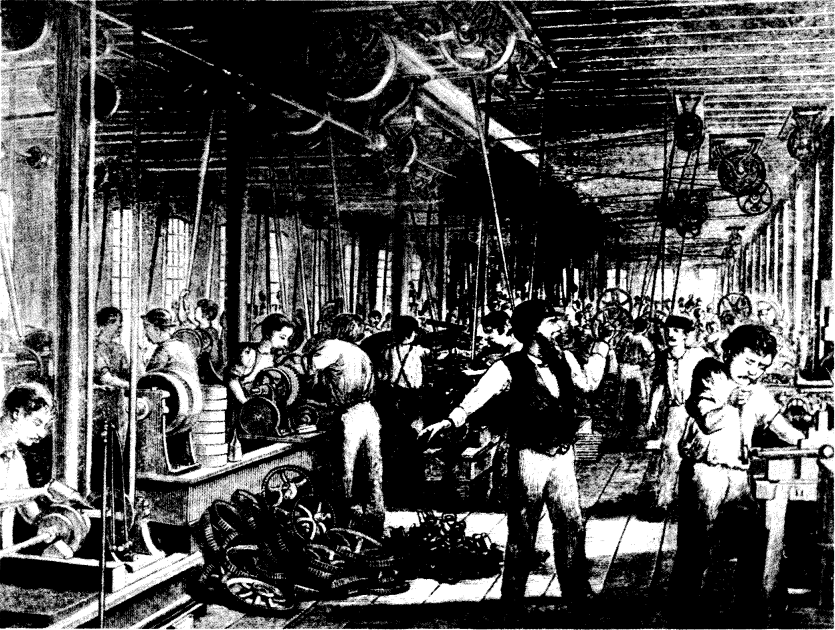

To understand the function of technical workers in manufacturing industries, we have to see that their role is both technical and ideological. They are entrusted not only with keeping production to certain pre-determined technical standards; they are also and mainly entrusted with maintaining the hierarchical structure of the labor force and with perpetuating capitalist social relations, that is, with keeping the producers estranged from the product and from the process of production.

There is ample documentary evidence for the fact that this second aspect of their role takes precedence over the first. But this fact has usually escaped the attention of capitalist societies, and only the Chinese cultural revolution has led Western observers to pay attention to it. Until recently, it was most commonly assumed that since industrial production in factories or large mechanical plants requires the division, specialization and separation of tasks, it was quite natural that minutely divided repetitive and unskilled tasks needed to be coordinated, supervised, planned and timed by people responsible either for part or for all of the complex final product, or for part or all of the work process: these people had to have both superior technical skills and intellectual and hierarchical authority.

But if we look into it more closely, we must ask: why must labor be minutely divided? Why must the narrowly specialized tasks be performed separately by different workers? The reasons usually given are: (1) narrow specialization requires less skill and training; (2) repetitive tasks enable the workers to work faster and more efficiently.

In truth neither of these reasons holds true.6 Experiments conducted mainly in the U.S. have demonstrated that productivity can be greatly enhanced by enlarging the jobs and replacing repetitive assembly line work by team work, i.e., by giving teams responsibility for a complex product and allowing each team to organize production as it deems most convenient. In this system, the repetitiveness and separation of tasks are abolished and workers are incited to achieve and to display a spectrum of skills, and to take over the coordination, planning, timing and even the testing of their production. Of course, the coordination of the different work teams and technicians or engineers undergoes a fundamental change: it ceases to be hierarchical and authoritarian. It cannot remain such. The system, in order to work, must rest on the workers’ consent, initiative and sense of responsibility; relations of cooperation and mutual trust between work teams and technicians or engineers become indispensable; the latter can no longer give orders and demand obedience; they must seek the workers’ consent and therefore have to explain and discuss each of their concerns. Moreover, they must be at the workers’ disposal, ready to help them solve problems they meet and to achieve improvements, modifications and innovations of the work process, the tools and the products.7

In this type of organization, as enacted in China and envisioned in Europe (mainly in Italy) by political and labor activists, sharp differences between workers on the one hand and technicians and engineers on the other hand tend to disappear. Production work and the acquisition of new skills and knowledge proceed together; working and learning or studying cease to be separated. From his [or her] early adolescence onward, everyone is at the same time both a producer and a student. No one is meant to remain blocked in unskilled, stupid and “inferior” jobs: an “evolutive profile” (or “career”) is sketched out in each industry whereby each worker’s work is to be progressively enriched, the reduction of working time being designed to allow free time for studying. The work process and production technology of course must be radically reshaped so as to allow for the maximum display of the producers’ capabilities and creativity.8

That such a reshaping of production technology should be possible without increasing the social costs of production to the whole economy is a demonstrable fact; experiments in the U.S. even demonstrate the superior micro-economic efficiency of the type of work organization that abolishes hierarchical authority and control and appeals to team spirit and creativity. The question to which we have to revert then is: why is such a type of technology not generally available? Why has capitalism consistently promoted a technology that rests on the minute and stupefying fragmentation of tasks: a technology that requires the hierarchic structure of the work force and the hierarchic separation of manual and technical and intellectual labor? Why does “rationalization” and “modernization” keep replacing skilled work and work teams with unskilled repetitive work that leaves most workers’ capabilities unemployed, that denies them the possibility of thinking and developing into complete human beings? Why does the capitalist system instead transfer most of the intellectual, creative and skilled dimensions of production work onto a pyramidally structured personnel of supervisors, technicians and engineers who receive an essentially abstract training and are instrumental in making and keeping the workers stupid?

That such a reshaping of production technology should be possible without increasing the social costs of production to the whole economy is a demonstrable fact; experiments in the U.S. even demonstrate the superior micro-economic efficiency of the type of work organization that abolishes hierarchical authority and control and appeals to team spirit and creativity. The question to which we have to revert then is: why is such a type of technology not generally available? Why has capitalism consistently promoted a technology that rests on the minute and stupefying fragmentation of tasks: a technology that requires the hierarchic structure of the work force and the hierarchic separation of manual and technical and intellectual labor? Why does “rationalization” and “modernization” keep replacing skilled work and work teams with unskilled repetitive work that leaves most workers’ capabilities unemployed, that denies them the possibility of thinking and developing into complete human beings? Why does the capitalist system instead transfer most of the intellectual, creative and skilled dimensions of production work onto a pyramidally structured personnel of supervisors, technicians and engineers who receive an essentially abstract training and are instrumental in making and keeping the workers stupid?

There is one main, fundamental reason: the hierarchical division of labor destroys the power of the workers over the work process and maximizes the bosses’ (or their representatives’) power of control over the work force. The minute division of labor renders the process of production totally extraneous to the workers; it robs them of the possibility of determining how much work they want to do, it prevents them from tampering with work speeds. It makes them work to the limits of their physical and nervous capabilities—a thing no one would do unless personally committed to the purpose of his work, and even then not permanently. In a word, the capitalist division of labor is functional to a system that rests on forced labor and that therefore can rely only on regimentation and hierarchical control, not on the workers’ consent and cooperation. To sum it all up, we have the following vicious circle:

(1) Since the purpose of production is not the satisfaction of the producers’ needs, but the extortion of surplus labor, capitalist production cannot rely upon the workers’ willingness to work;

(2) the less capitalist management wishes to rely upon the willingness of the workers, the more extraneous, regimented and idiotic work has to become;

(3) the more extraneous, regimented and idiotic work becomes, the less capitalist management can rely upon the workers’ willingness.

Hierarchical regimentation thus appears to be a necessity that flows from production technology; but in truth it is built into production technology insofar as the latter is itself a reflection of the social division of labor.

Whether we like it or not, we must see technicians in the manufacturing industries as key instruments of the hierarchical regimentation required by the capitalist division of labor. Their role is to oversee the domination of mechanical processes over living labor; their role is to make sure thereby that the maximum labor and surplus value is extracted from each worker. The role is to dequalify workers by monopolizing the technical and intellectual skills required by the work process. They embody the dichotomy between manual and intellectual work, thought and execution. They hold significant financial, social and cultural privileges. They are the workers’ most immediate enemy: they represent the skill, knowledge and virtual power of which workers have been robbed. In a machine tool shop, every one technician that is hired will turn five, ten or twenty hitherto skilled workers into unskilled underdogs, thereby enabling the boss to pay them unskilled wage rates.

I shall conclude this chapter by reporting a recent conversation with a young technician in a machine tool factory. He had been to a technical school and was very proud of his knowledge. He earned twice as much as the workers he was supervising. When asked what he knew which the workers did not, he replied: “I have studied calculus, mechanics, and am a good draftsman.” I asked him: “Do you ever use calculus in your work?” “No,” he said, “but I am glad I have learned it. It’s good training for the mind.”

I then asked him: “What skills, besides calculus, do you have which workers have not?” “I have a more comprehensive insight,” he said, “into what it’s all about.”

“Could workers acquire such an insight,” I asked, “without having been to a technical school?”

He replied: “They might get it through experience, but it would take them time.”

“How long?” I asked.

“Oh, at least five to six years,” he said.

This technician had been to a technical school for three years. You will have noticed that, in his view, his hierarchical and social privileges and superiority rested mainly on his knowledge of calculus. But he had never used calculus in his work. Calculus was the cultural status symbol that made him socially different from the workers. Because it was the only thing he knew which the others could not learn from experience, calculus gave him a sense of authority and of superiority over them. We have here a crystal clear illustration of the way in which the school system is instrumental in building social hierarchization. Indeed, in our example, the technician’s superiority did not stem from superior useful knowledge. In his own words, the useful knowledge he held could be acquired by workers in five to six years. His hierarchical superiority stemmed from superior useless knowledge. He had been trained in calculus not to become more efficient than a worker, but to become superior to a worker. And the workers had not learned calculus not because they were too stupid to learn it, but because they were meant to remain culturally and therefore hierarchically inferior, whatever their skill.

From a political viewpoint, we must therefore consider that there is an unbridgeable objective class distinction between technical supervisory staff and production workers. This class barrier can be overcome only by a powerful ideological thrust enhancing class consciousness. Mainly in situations of acute crisis and upheaval, technical supervisory personnel can be brought to side with the working class and to feel one with it. This possibility rests on the fact that technical and engineering personnel, though they hierarchically oppress the workers, are themselves frustrated, estranged and oppressed from above. Vis-a-vis their superiors, they are in the same situation as are their inferiors vis-a-vis themselves. When, during radical outbreaks in factories, the workers attack the capitalist division of labor and demand or even practice self-rule and equal pay for all, the sheer ideological appeal of their demand can win over technical and scientific personnel. I saw this happen in May 1968 in the Thomson-Houston plant near Paris, where research engineers came out in favor of equal pay for all. It must be added, of course, that some of them were highly politicized. We cannot expect, however, that such a demand should spring up in normal times. All we can do in times of uneasy and restless “peace” is to impress upon technical personnel that they have more to win than to lose by the abolition of hierarchical regimentation and privilege. To prepare the ground for this abolition, both culturally and materially, technicians must be stimulated to question their role on the following basis:9

(1) they must endeavor to distinguish between their particular technical or scientific skills on the one hand, and their role in the hierarchical division of labor, on the other hand;

(2) they must endeavor to “socialize” their particular skills, that is, to look for the ways and means whereby their superior knowledge could be made accessible to all, could cease to be a privilege, could cease to be professionally exercised by a few to the detriment of all, which entails the reshaping of the language of science and technology, a new definition of skills, of the learning process, and of the work process;

(3) they must refuse the social privileges and the hierarchical position of power attached\ to professionalism in the capitalist division of labor.

In short, the sharpest possible line must be drawn between specialization and privilege. Whereas specialization cannot be abolished in the foreseeable future, privilege can. There is no intrinsic necessity to attach privileges of status, power and money to certain skills. The basis for such priviliges cannot be considered to be the scarcity of the more intellectual skills or of the capability to acquire them. It is questionable whether this scarcity has ever existed and it certainly has virtually ceased to exist: on the contrary, there is an actual or potential overabundance of intellectual skill. Scarcities that can still be observed cannot be ascribed to scarce talent or lack of capability to learn, but are a result of the class character of educational institutions: as we have seen in the example of the young technician, so proud of his mathematical skills, education aims at imbuing a minority with a feeling of elitism and is instrumental thereby in reproducing the hierarchic stratification of labor required by capitalist social relations. This result is reached through teaching methods that make the acquisition of abstracted intellectual skills difficult for children of less educated parents and by identifying good school grades with a right to privilege and to social promotion. The schooling system is a key instrument of social hierarchization: it registers a differentiation of skills and learning capabilities because it produces it. 10

III.

It may seem at first that the class analysis which we have outlined so far does not apply at all to the growing stratum of technical and scientific personnel which, working in big engineering firms and in so-called scientific industries, is itself subjected to the capitalist division of labor. In Italy, France, and Great Britain, we have witnessed in recent years mass rebellions and strikes by draftsmen, engineering and technical personnel of the computer industry, research workers in the laboratories and research institutes, project engineers in large firms of consultants, etc.

In many instances, mass rebellion was motivated by the technical and scientific workers’ frustration and humiliation at being submitted in their work to the same job evaluation, fragmentation and hierarchical regimentation as ordinary workers. Where intellectual workers no longer hold hierarchic authority over manual labor but are themselves producers of non-material commodities such as information, projects, patents, and innovations, they experience the proletarianization of their labor and their alienation through extraneous work processes and stupefying specialization.

But we must be careful not to jump to hasty conclusions and not to miss the inherently ambiguous character of most intellectual workers’ rebellions. We cannot consider these right away as proof that intellectual workers join the struggle of the proletariat because they in fact tend to be proletarianized. Such a conclusion would be legitimate only if intellectual workers actually joined up with manual workers on a class basis and fought together with them for common goals. Though there are cases where this has happened, it is far from being the rule. In most instances, intellectual workers have not revolted as proletarians, but against being treated as proletarians. They have rebelled (1) against the hierarchical division, fragmentation and meaninglessness of their work and (2) against their proletarianization and the loss of all or part of their social privileges … The anti-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian dimension of their rebellion was, in most cases, inextricably linked with demands aiming at recovering some of the privileges that were attached, in earlier times, to the intellectual workers’ middle class status. Hence the ambiguity of their protest movement, a movement that may be said to be anti-monopolist rather than anti-capitalist, corporatist rather than proletarian.

To make clear this ambiguity, we have to examine the kind of training most technical workers are receiving, and their motivation in accepting such training.

Post-secondary education, in almost all countries, is sharply divided into two branches: the more traditional liberal universities, on one hand, and the technical and engineering schools, on the other hand. The content and the methods of education differ significantly in these two branches. Whereas the teaching process in universities may be rather informal, it is quite strict and disciplinarian in technical and engineering schools. Whereas universities as a rule aim at conveying a certain knowledge and at training students to become intellectually self-reliant, technical and engineering schools aim at conveying both knowledge and practical skills, and at shaping the personality of the student so as to make him or her fit into the hierarchical and authoritarian order of the factory or the laboratory. University graduates are supposed to acquire and develop a critical intelligence that should enable them to work independently as free professionals, research scientists, private entrepreneurs or teachers; their degree does not prepare them for a definite job and, actually, may leave them jobless. Technicians and engineers, on the contrary, are trained for a job they have chosen and which they know will position them in a definite place within the social hierarchy and the division of labor. They have chosen this particular kind of training and this particular job for two reasons: (a) their social origin leaves them little hope of becoming anything but salaried employees; they do not have enough time and money to attempt an independent career and to run the risk of not finding a job as soon as they graduate; (b) they are “upwardly mobile” and aim for a salaried position which will be better than that of an ordinary worker or employee, but which will hardly carry them to the “top.”

They may therefore be described as being essentially lower middle class, Their hope of positioning themselves on an intermediate level between top and bottom implies that they are prepared to serve unquestioningly the goals and purposes of the ruling class. And this is precisely what the technical and engineering schools prepare them to do. Technical training, in its essence, is indifferent to goals and purposes; it specializes in paying attention to the ways and means to reach preset goals and purposes. It dispenses a typically subordinate culture: not one that deals with defining the so-called higher values of society and the meaning of things; but one that prides itself on being value-free and therefore capable of devising efficient means to enact any values others may set. The divorce between so-called higher culture—the humanities, the liberal arts—and technical skill and knowledge is an essential part of the social division of labor as embodied in technical education.

Technical schools and institutions are thus instrumental in producing a particular type of individual. Or, to put it the other way around, those who will put up with the regimentation, repressiveness, discipline and deliberately unattractive programs of technical schools are the kind of persons capitalist industry needs. They are a hand-picked minority. As you know, a very large proportion of young industrial workers dream of improving their qualifications and becoming technicians and engineers. They dream of this to escape the dreadful embarassment and boredom of repetitive work. They could become well qualified if the education and programs were rendered attractive and pedagogically efficient. But the programs are devised in such a way as to discourage, repel and eliminate between one-half and three-fourths of the youngsters who would have liked to learn.

In Europe and, to a lesser degree, in the U.S., the highly selective character of high schools and technical and engineering schools is something deliberate: as long as manual and unskilled jobs in industry and the service sector represent a significant proportion of all available jobs, the schools must produce a sufficient proportion of failures for whom the “low level” jobs will remain the only choice. The production of failures and school dropouts is as important to the reproduction of hierarchical social relations as the production of school graduates: a set proportion of adolescents must be persuaded by the impersonal process of schooling that they are incapable of becoming anything better than unskilled labor. They must be persuaded that their failure to learn is not the school’s failure to teach them but their own personal and social shortcoming. (Conversely, those who do well at school must be convinced that they are something like an elite, that they will rise above the working class and that their success is due to their hard work, self-denial and ambition. Technical schools make sure that the successful graduate will feel condescending towards workers and submissive towards those above him.)

In Europe and, to a lesser degree, in the U.S., the highly selective character of high schools and technical and engineering schools is something deliberate: as long as manual and unskilled jobs in industry and the service sector represent a significant proportion of all available jobs, the schools must produce a sufficient proportion of failures for whom the “low level” jobs will remain the only choice. The production of failures and school dropouts is as important to the reproduction of hierarchical social relations as the production of school graduates: a set proportion of adolescents must be persuaded by the impersonal process of schooling that they are incapable of becoming anything better than unskilled labor. They must be persuaded that their failure to learn is not the school’s failure to teach them but their own personal and social shortcoming. (Conversely, those who do well at school must be convinced that they are something like an elite, that they will rise above the working class and that their success is due to their hard work, self-denial and ambition. Technical schools make sure that the successful graduate will feel condescending towards workers and submissive towards those above him.)

Consciously or not, such a selective schooling system aims at dividing the manual and technical workers into two distinct strata, persuading the latter that they really belong to the middle classes and are entitled to some social and financial privileges. This attempt at socially upgrading the technical worker is not only a hangover from earlier times, when technicians were working as supervisors rather than as production workers: it is also motivated by capitalist management’s need to have costly and highly productive machines supervised and served by reliable, trustworthy people who will feel loyal to. the corporation and the system and not be inclined to take the technical power they wield into their own hands, or even to demand political and economic power for the working class. People who actually control the more or less automatic processes of vital production must to some extent be co-opted into the system’~ privileged strata and made blind to their class position, lest the system’s smooth and safe functioning be jeopardized.

The effectiveness of this strategy of co-optation is dependent, however, on the (subjective) reality of the privilege it can confer. No great difficulties may be encountered as long as the stratum of technical workers is only a minority. But when the proportion of skilled versus unskilled jobs becomes reversed, contradictions tend tend to explode. This situation has presently been reached in the U.S. and, potentially, in most of Western Europe. Student and high school rebellions must be seen in this perspective. Most advanced capitalist societies are presently in a period of uneasy transition: schools must keep producing a proportion of failures—about two-thirds in Western Europe versus about one-third in the U.S.—so as to provide the necessary unskilled labor to the economy. But it is already clear to most that unskilled jobs are disappearing rapidly and that post-secondary education is becoming a prerequisite to finding any—however boring, narrowly specialized and repetitive—job. The arbitrariness of the schooling system’s inbuilt selectiveness is therefore becoming obvious: the schools reject a certain proportion of students not because it would be impossible to educate them—the contrary has become quite clear—but because, for the reasons indicated above, the system does not care to educate them: it must prevent them from acquiring skills and knowledge that would make them “unfit” for the low grade jobs.

On the other hand, as the majority of jobs tend to require some post-secondary training, the link between such training and the privileges it conferred in the past can no longer be maintained. According to recent American statistics11 the expected lifetime income of youngsters with one to three years of college is only 6.24% higher (i.e., $119,000 against $112,000) than that of youngsters who have a high school education. Hence the following explosive contradiction: post-secondary education remains selective, competitive and requires the kind of social 28 attitudes that would be expected from upwardly mobile adolescents, but the jobs onto which junior college and technical education lead hold hardly any privilege—whether financial or social or intellectual—over unskilled jobs: most trainees of technical school or of junior colleges are clearly destined to become the laborers of the technically advanced industries and to perform the so-called “post-industrial society’s” ungratifying and frustrating work.

The choice confronting young technical workers is therefore quite obvious: either, having put up willingly with the regimentation and selectiveness of a schooling system that promised them privileges and promotion, they rebel against their regimentation at jobs that do not fulfill the system’s promises and frustrate their desire for respectability, initiative and creativeness; or, they find out while still in training that the schooling system’s promises and values are a big swindle anyhow, and they rebel against regimentation at school first and against regimentation at work later. Why indeed should they put up with the disciplinarian and authoritarian training methods since “learning” at school will secure them neither a “higher” social position nor gratifying work allowing for some display of initiative and creativity? Since good performance at school is irrelevant in both respects, well then, fuck the school and fuck the system and instead let’s do and learn things that are enjoyable and hold some intrinsic interest. In one word, the motivations that could incite youngsters to put up with the school and with the jobs it prepares them for are going bankrupt; the present crisis of and revolt against the educational system and work organization is the consequence of this bankruptcy.

Only the last of these two attitudes holds real radical potentialities. It goes beyond (depasse) the inherent ambiguity of the first attitude, which is a rebellion against both the alienation of work and the proletarianization of the technical workers. When Serge Mallet and others wrote about the “new working class” ten years ago, they missed this ambiguity and still drew a line (legitimately, at that time) between the “old” working class, caring mainly about wages, and the “new” one, caring mainly about “qualitative goals”. As technical or post-secondary education and the technicization of work become the rule, the distinction between the “old” and “new” working class is becoming obsolete, at least with younger workers. To them, technical work no longer holds much, if any, privilege over traditional production work. They know or sense that the technical worker, whatever his skill, is the underdog and the proletarian of “technological society”. They have learned in schools, in their early teens, that the system channels towards technical disciplines, studies, and professions, those whom it condescendingly considers “unfit for anything better”. They rightly feel their teachers or professors to be the prefiguration—or the valets—of the bosses and cops who will exploit them and beat them down in the near future; and their revolt against the stupidity of regimentation at school goes hand in hand with the revolt against the work organization and the hierarchical division of labor. They know that their technical skills, which will be obsolete within five years, anyhow, are no better than traditional manual skills and hold no hope of escape from working class boredom and oppression.

The ground is thereby laid for the political and ideological unification of technical and manual workers of the “new” and the “old” working class—at least in the younger generations, and for a common onslaught against the capitalist division of labor and the capitalist relations of production.

But this objective possibility for unification must still be made conscious by actions for the proper goals and on the proper ground (terrain). The goals must of necessity be those of a “cultural revolution”: destroying the inequalities, hierarchizations and divisions between manual and intellectual work, between conception and execution; liberating the creative potentials of all workers which the schools as well as the work organization stifle. The ground must be both and at the same time the factor where the work force is oppressed, intellectually mutilated and psychically destroyed, and the school where the “human material” is shaped so as to fit into the hierarchical factory system. The crisis of the reproduction of capitalist social relations and of the capitalist division of labor—i.e., the crisis of the school—must reach down to a direct attack against the hierarchical division of labor in the factory; conversely, the attack must reach up to an attack against the educational system, which is the matrix of the division of labor. Education and production, learning and working were separated from the means of production and from culture and society overall. Therefore the re-unification of education and production, of work and culture,12 is the only correct approach in a communist perspective.

— Andre Gorz

CRITIQUE “…privileged status does not negate the concrete reality of the proletarianization of scientists and technologists.”

Gorz strangely takes an undialectical view of the transformation of consciousness when he concludes that because technical and scientific workers currently “are not prepared to help workers into self-organizing the work process and into adjusting production technology to their physical and psychic needs,” they “would be of little use in a society bent on meeting the more basic social and cultural needs of the masses.” (p. 7) Individualistic, competitive, racist, and sexist workers would also be of little use in a communist society. But the revolution does not await the coming of the socialist person. The socialist person is produced by the revolutionary struggle13:

Both for the production on a mass scale of this communist consciousness, and for the success of the cause itself, the alteration of men on a mass scale is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.

I have participated in a wildcat strike in which so-called “racist” workers struggled arm-in-arm with their black comrades. Their common class interest and need for each other in their struggle forced the whites to overcome their racist ideologies. Likewise, as the proletarianization of the technological workforce progresses and is resisted, awareness of the common enemy, increasing interdependence among fragments of the working class, and development of a revolutionary party program will overcome the elitist attitudes and privilege-seeking behavior of engineers, scientists, and technicians.

Although Gorz does employ dialectical reasoning to clarify how the role of technologists has changed from being essential for the development of the forces of production to maintaining the capitalist relations of production, his dialectical analysis curiously stops before the period of conglomeration. The tremendous financial-administrative concentration now taking place has been made possible by the very engineers and scientists whose function it is to maintain the hierarchic control necessary for capitalist production. It is they who have developed the hardware and software necessary for centralized control over mousanas ot decisions about what to produce, where, and in what quantities. But the very success of these scientists and engineers is leading to their proletarianization. By merging enterprises, fewer technologists are required to maintain the control necessary for capitalist production. Contrary to Gorz, then, the productive forces developed by the technologists are making possible the restructuring of capitalist relations of production and rendering many scientists, engineers, and technicians superfluous. For example, when England’s three biggest electrical companies were merged, about two thousand scientists lost their jobs. This story is being repeated throughout Europe according to the New York Times (3/13/73). Although we may conclude that most of those scientists were not essential to the material process of production and were attempting to create “new opportunities for profitable capital investment,” once they are fired, they become a reserve army of technologists, helping to drive down wages of scientists, engineers, and technicians who are “required by the process of material production as such … ” (p. 6&7) This is because the laid-off scientists and technologists must now compete for jobs with those in production. Once re-employed (now in technological work materially required by production) the scientists and technologists formerly in nonproductive work become a privileged stratum within the class of wage workers who produce surplus value. Previously, those laid-off shared in the surplus value produced by blue collar workers and productive scientists and technologists.

Gorz would disagree that the technologists displaced by the increasing concentration of capital into larger merged corporations become part of the working class and consequently, an important part of the revolutionary struggle. [Gorz is referring to their consciousness. He recognizes the objective fact that “they experience the proletarianization of their labor. ” (p. 26 ), Eds.] Gorz believes that those displaced who were not essential to material production as such cannot transfer their skills to become essential and must remain unemployed or enter another occupational stratum outside the working class, such as the service occupations, e.g., insurance, real estate. But Gorz is just plain wrong. There have been several studies showing that the skills of the highly specialized defense engineer, whose primary function has been to create new markets by designing elaborate and costly weapons and thereby rendering previous weapons obsolete, is quite transferable to civilian industry. The major problem in finding employment for laid-off defense engineers is the reluctance of civilian-oriented companies to hire technologists who are not cost-conscious but are primarily quality-conscious. That is, non-defense companies are afraid former defense engineers will hurt profits. But such a problem could hardly be of concern in a communist society.

Their privileged status does not negate the concrete reality of the proletarianization of scientists and technologists. The reality provides the basis for the transformation of consciousness in common struggle with blue collar workers. Gorz himself admits that such a transformation has occurred in France. Cooperative resistance among blue collar workers and technologists to large-scale layoffs may not go beyond the militance recently exhibited by Dutch workers who occupied a factory for eight days and succeeded in saving 6,000 privileged and unprivileged jobs. It will take a, revolutionary party to present a program for eliminating the routine, the fragmentation, the meaninglessness, and lack of control over the choice of projects that the growing mass of engineers and scientists face.

— Jeff Schevitz

CRITIQUE “We must find a common interest in the overthrow of capitalism, instead of appealing to some problematic sense of equality.”

Some British comrades sent us a 10,000 word transcription of their discussion of Gorz’ “Technical Intelligence and the Capitalist Division of Labor”. Though we could not handle material in that form (we really need publishable articles), we are printing here a summary by one of the discussants of his views. We hope the British group will continue the discussion and collectively synthesize an article; for there may be important differences among the advanced capitalist nations with respect to the class position of technical workers and the function of their work (see also the West Germany chapter report, p. 43).

Gorz’ very stimulating article provides some useful starting points for analysis—but that’s all; it fails to follow through and come up with—a complete or even adequate analysis. It points a finger at nasty effects of capitalism, but it does not come to grips with the problem of establishing socialism.

There is a general tendency in Gorz’ article to focus on problems none of which in practice are necessarily beyond the adaptive capacity of welfare-state capitalism, enlightened by policy research, organization theory, and job-satisfaction technology. For example, he calls for ending the alienation of research from production and use. But this demand is not revolutionary; on the contrary, it is a demand that bourgeois science attempts to fulfill. As Gorz himself points out, research and development are important aspects of production in modern capitalism. The capitalists and their government bureaucrats are also calling for a closer connection between R&D and production and use.

The danger with this kind of analysis is that it could go the same route as the radical analyses of the 1930’s. Thus J.D. Bernal [Britain’s leading Marxist scientist of the thirties. See, for example his The Social Function of Science, MIT Press. Eds.] became the father of science policy in the postwar growth period. None of the problems have to be tackled in a way which must lead to the development of revolutionary socialist praxis among scientific and technical workers. Granting that these demands ought to be employed by socialist revolutionaries as cracks to drive wedges into, still the outcomes are far from being necessarily revolutionary as Gorz (and I) would like. Gorz does not help us to weigh the mystifying potential of new capitalist rationalization strategies, the problems of unmasking bourgeois ideology, and of creating a vital socialist (as distinct from reformist) praxis.

The difficulty remains to understand exactly how technical theory and practice must be transformed if we are to transcend the capitalist structuring of these in a way that is fundamentally in contradiction to the continuance of capitalism and therefore revolutionary. To begin with, we must know how they are presently structured. For example, which of the following are structured by capitalist social relations, in what way, to what extent; and how necessary to capitalism is the structure:

- technical/experimental practice (behaviorally defined in terms of information, material, and symbol manipulation),

- the theory behind/in technical practice,

- the total repertoire of technical practices,

- social practice in technical and economic institutions,

- social relations in technical institutions.

The attacks on economic and technical determinism pleased me; but the ever-present problem with theories of proletarianisation—the question of false consciousness—remains. Gorz indicates potential sources of revolutionary energy, not potentially revolutionary classes. Consequently, his suggestions amount to counter-ideology mongering: “Try to destroy the mental workers’ consciousness of otherness and superiority in whatever ways possible.”· While this is necessary, if we cannot go further than that, then we have abandoned Marxian strategy and fallen back on Utopianism. We must find a common interest in the overthrow of capitalism, instead of appealing to some problematic sense of equality.

Strategically, I suggest exposing the limits of rationalization and participation, thus demonstrating the class structure—the division of society into “decision makers” who make the decisions that sustain capitalist social relations, and “others” who carry out these decisions at all levels. The present tendency towards decentralization of technical decisions results in technical workers being required to obtain operational solutions to problems of adaptation, stabilization, and communication—problems, the solution of which are instrumental for carrying out the basic decisions. But the technicians do not participate in the basic decisions—on what to produce, at what cost, in what quantity, at what quality, for whom. We must develop and propagate an analysis showing how these basic desisions are systematically divorced from technical questions such as how to coordinate production processes within preset constraints, etc.

The fragmentation of the worker—into voter, consumer, parent, pupil, worker, etc.—must be shown for what it is, a strategy of “divide and rule” at the level of the individual subject. This apparent irrational fragmentation of the whole person can then be contrasted with the system of manipulations of these fragments (polls, advertising, educational system, family hierarchy, personnel departments, job satisfaction, etc.) in accordance with a specifically capitalist rationality of control and exploitation in order to realize surplus value for capitalist interests.

— Mike Hales

CRITIQUE “…increasing proletarianization…cannot be answered by innovation…The attempt to resolve one set of contradictions heightens another.”

The Stonybrook group submitted some notes on a discussion they had of the Gorz article. The following is a distillation of a few points:

- The article proposes that technical innovation is the means by which the capitialist system avoids the saturation of demand. But saturation of demand and overproduction is only one of the contradictions inherent in capitalism. Another contradiction—the increasing proletarianization and pauperization of the proletariat—cannot be answered by technical innovation. That the U.S. capitalist system has managed to postpone the critical point of this contradiction is evident. How was this possible? Perhaps the temporary alleviation of internal crises of capitalism is to be found in imperialism, which is the logical outcome of capitalism’s struggle for survival.But the system has its difficulties. The military and government spending abroad necessary to maintain imperial control accounted for two thirds of the current deficit in the U.S. balance of payments. The trade tariffs and devaluation, used to address the balance of payments problem, is bound to reduce the levels of consumerism (due to increased prices)—and hence saturate demand. So the attempt to resolve one set of contradictions heightens another.

- The discussion of the role of the school system in laying the basis for capitalist exploitation was important, especially Gorz’ comments on the meritocracy myth and its reinforcement. The ruling class, by emphasizing individual success and peer competition, tries to restrict the development of a class identitiy. If the role of intellectuals and the technical intelligentsia is ambiguous, as the article claims, then we must ask how they are to be treated within the left?

- Given the entrance of the lower elite, engineers and scientists, into the ranks of the working class, what practical political conclusions can we draw from Gorz’ analysis?

* The myths referred to earlier must be exposed as such. We must actively fight the hierarchical organization, based on economic and social inequality, of capitalist institutions. The People’s Republic of China could be cited as a positive example to counter several current fallacies about the inevitability of certain relationships.

* As an application of theoretical study, we should criticise, from a Marxist perspective, events occuring today and then publicize these critiques.

* Since education is the daily practice of most SESPA people here, we should create study programs that show how the individual is coopted into the capitalist framework.

* Question: should we continue to do the kind of scientific research that we are now performing?

* We should participate in the everyday struggles of working people, even if they are not scientific workers. In particular, contact with the Eastern Farmworkers Association should be established.

- Some of us made the criticism that unless SESPA developed a definite political line, our activity would remain as random actions by well-meaning individuals.

— Stonybrook SESPA

CRITIQUE “The Gorz article needs to be distilled…. Simplified, turned out for mass culture use.”

Gorz reflects my own opinions about work. Some time ago I accepted the fact that many boring, repetitive industrial tasks were necessary, but they drove me insane at the 40-48 hour week level. I have a B. A., but cannot accept the heirarchical regimentation required of me in jobs I could take (I have had three fellowships for graduate work and dropped out of all three). So I work manually and feel insane. I have repeatedly been offered “promotions” in line with the Gorz idea of getting people to squeeze out a better profit for the bosses. I have said “No” because I don’t take bribes. Plus, I believe Gorz is right about the elitism of schools, turning out more elites while acculturating the masses to do the boring work. The arrogance of class divisions in work is at the center of sloppy, unhappy, halfass, bullshit work. I know this and know, from prolonged working at mindless tasks (dish washing at large restaurants), that it isn’t necessary except to maintain the capitalist yacht.

The Gorz article needs to be distilled and used by the whole group and movement for it deals with the center of the work crisis. Distilled—simplified, turned out for mass culture use.

— Joe Neal

Although individual moralistic acts seldom contribute to political struggle, class consciousness is raised when a worker in the context of a collective struggle affirms her/ his identification with fellow workers by an exemplary refusal of privilege. We hope this is what Joe means. The last paragraph brings up a paradoxical aspect of Gorz’ article: it is “culturally and semantically disconnected from general comprehensive culture and common language” (p. 7) and was published in an abstract academic philosophical journal edited by persons of questionable political practice (see the article, “Marxist Scabs…”, p. 22 in this issue).

ENGINEERS: AN EXAMINATION OF SOME MYTHS AND CONTRADICTIONS CONCERNING ENGINEERS

Engineers are a highly stereotyped group. Non-engineers tend to view them as thing-oriented rather than people oriented or more pejoratively as uninteresting, compulsive and non-verbal. Engineers themselves often subscribe to this stereotype too. Thus a mathematician who had once worked as an engineer commented about our work, “Studying engineers? Isn’t that really dull?” When we first embarked on a study of engineers we were deep down operating with similar preconceptions, although one goal was to shed some light on these notions and to explain them. Stereotypes tend to include some common elements of a group. If they bore no resemblance to reality they would not be used, but they often represent one-sided or exaggerated views. Few other occupational groups are seen as containing such a narrow range of personality types. We would here like to examine some of the common myths about engineers, to show what basis there is in reality and to attempt a sociological explanation of that reality. As already mentioned engineers are frequently viewed as primarily object oriented; they are also seen as overspecialized and as apolitical.

Object Orientation

The engineers’ self-identification as object or thing-oriented often implies that they do not relate well to other people. The most extreme example of such alienation from others is the Lockheed syndrome, primarily found in the defense industry. Aerospace engineers, in particular. are said to suffer from this affliction. It is characterized by such single-minded pursuit of one’s engineering work that relations with others and leisure time pursuits are heavily colored by work experience. As fathers and husbands these engineers withdraw to only minimal communications with their families, putting them on an emotional starvation diet, which is then blamed for other problems that may occur in the family. These patterns are almost exclusively looked upon as psychological disorders, and the recommended cure is indivual or group therapy. Little attention is paid to the dehumanized work environment in which engineers are expected to put in 50 to 60 hours a week (at no extra pay) in the service of primarily destructive technology, when the ideology of training has stressed the design and creation of useful things.

Although the Lockheed syndrome refers to a rather extreme case, preoccupation with things rather than with people is in large measure expected of and preferred by engineers. Moreover, it is not confined to engineers. Present day American culture with its emphasis on acquisition and consumption is in fact very materialistic. Where “Canada Dry tastes like love” and Coca Cola creates “perfect harmony”, all problems can be treated as being technical. Particularly males in this society are supposed to be unemotional; to conform to this image it is safer to manipulate objects rather than to relate to people. There are strong pressures early in life that equate masculinity with knowing how to fix and build things.

Thus although object-orientation is to some extent required of all men, engineering tends to encourage those who identify particularly strongly with this value. This selective process assures that those who go through the prescribed training process in engineering are well-adapted to the technical requirements of industry. The lack of emphasis upon or total absence of the humanities in our technical schools is quite consciously designed to turn out people who are completely devoted to their job. As a result such training produces, in the words of an MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) professor, “social Neanderthals.” The personal costs of such one-sidedness are considerable and very painful once the source of one’s supposed fulfillment is removed, i.e., when engineers become unemployed. It is in this situation that the shortcomings and contradictions of dehumanizing work become particularly apparent. In our study we found that, despite their lowered self-esteem and economic insecurity unemployed engineers seemed somewhat more expressive and people-oriented than the employed ones. Despite the relative lack of options in terms of real jobs available, the unemployed are in a position where they can and must consider a wider variety of alternatives, whereas the employed engineers are under even more pressure to conform now that the economic squeeze is on. In conclusion there is a great deal of truth to the description of engineers as object-oriented. This behavior is functional and necessary for the performance of their jobs, but it is dysfunctional to their relationships with others. If job pressures are removed or modified, as they are in the case of the unemployed, engineers may in fact begin to place an increased value on their social relations, thus lending support to the idea that extreme object-orientation is a form of alienation.

Rising unemployment also puts pressures on those who remain employed. But without unions engineers are inclined to compete among one another to remain employed. As long as thing-orientation makes them “better engineers” then, we cannot assume that unemployment will significantly alter the thing-orientation of engineers as a group. On the other hand, insecurity of employment is just one of the many factors that can erode the sense of gratification engineers need to feel in their work. Other aspects of proletarianization that tend to remove the possibility of gratification from engineers’ work bring into play the contradiction between the dysfunctional role of thing-orientation on their social relations and its functional role in their engineering work. An explosive situation can thus arise as the rewards of thing-orientation on the job are eroded; a powerful reservoir of anger can be released as engineers discover that the jobs they have loved return them neither sufficient wages, nor security, nor a craftman’s gratification, and yet have alienated them from human relations.

Specialization

Newspaper accounts, articles in journals of the engineering professions, and sterotypes popular among engineers and non-engineers, had predisposed us to expect very limited flexibility in skills. We were therefore quite surprised to find a lot of evidence in the interviews that defense engineers are not nearly as overspecialized as they are made out to be. Before examining the function performed by the persistent myth of specialization and showing in what ways it does not hold, let us first distinguish between specialization and fragmentation.

Engineers are affected by fragmentation as much as are production workers. The objective causes of this are twofold: (1) The increasing complexity of technology requires the breakdown of work processes into ever smaller components which can be handled by an unskilled workforce and also transformed into machine processes, but, (2) as Gorz14 and Marglin15 point out, it may not merely be the requirements of technology that dictate this fragmentation, but also the need to control the workforce and make it dependent on the capitalists. Fragmentation is thus not only technologically required but also ideologically necessary. Both workers and engineers do fragmented jobs; how their work fits into an overall scheme is not generally known by them. The engineers may be working on a larger fragment, that’s all. Whereas fragmentation is a characteristic of the organization of the work process, specialization is a property of the worker. An engineer who remains capable of doing only one or a few fragments of the work is specialized. However because of the relatively high skill level required to accomplish an engineer’s work fragment there is a tendency for this expertise to become a source of status. Not so, of course, with less skilled workers; no prestige is derived from being an expert at the lowest end of the totem pole, because the training period is short and inexpensive, and the worker is therefore easily replaced. As a result continued performance of a job fragment takes on quite a different meaning depending on its place in the total hierarchy.

Engineers find themselves today caught in the middle between workers and management. The carrot held out to them, and reinforced by the professional ideology that most still adhere to, is the possibility of moving up into a management position. Working against this is the stick of increased proletarianization. The proletarianization of engineers, frequently remarked upon, is related to their great increase in numbers due to the requirements of complex war technology. But (as Gorz points out) in their self-perception engineers do not yet (at least in the U.S.) see themselves as having more interests in common with production workers than with professionals as a separate category or with management. Interestingly enough, the appeal peal of becoming part of management is not only the higher wages and (apparent) greater security but also the opportunity to participate in the production process in a less fragmented way. Corporate management thus plays the contradictory role of fragmenting the work, consequently requiring more specialization, while rewarding those who “see the whole”—and are willing to manipulate others.

In the war and space industry of the U.S. there is little long-term production of any one product. Consequently fragmentation that may serve corporate purposes for control and profit maximization also would tend to make a corporation less flexible in its ability to respond to the never ending innovation for war. The two ways this problem has affected engineers are (1) an unusual mobility from firm to firm selling their specialization and (2) considerable non-specialization (actually serial specialization) as engineers complete their fragment of one project and retrain for a new fragment of a new project.

The cutbacks that created the recent increase in unemployment among engineers resulted in corporations contributing to the specialization myth to the benefit of their own profits. They blame the engineers for overspecialization and refer to the “rapid obsolescence of engineers”, thereby justifying the practice of hiring newly graduated engineers, on the grounds that they have just learned the latest techniques. Most of the engineers who had experienced unemployment were aware of the economic motivation of corporations that lay off highly paid middle-aged men and replace them with people whom they pay 50% less. (They also spoke of a practice called “recycling of engineering salaries” which involves dismissing engineers and rehiring them a few months later with a several thousand dollar cut in salary.) Actually most of the people we interviewed stressed the importance of on-the-job training which contradicts the image of the recent graduate as expert.