This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

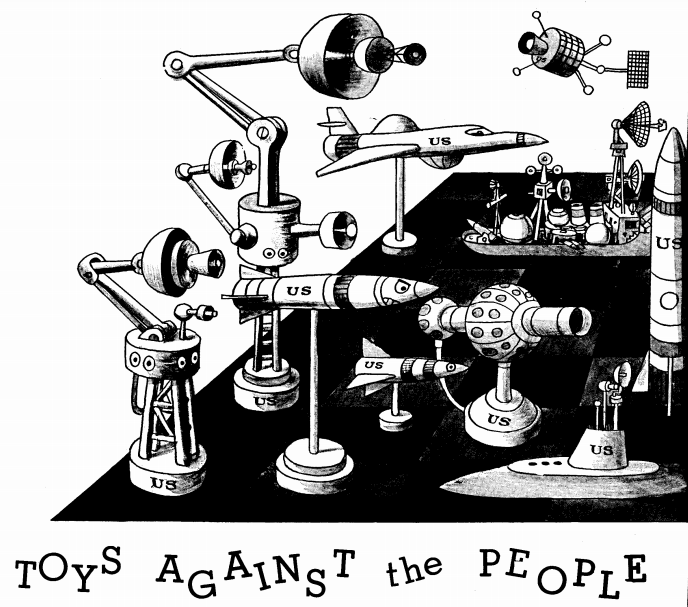

Toys Against the People (Or Remote Warfare)

by New England Action Research

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 5, No. 1, January 1973, p. 8 – 10 & 37 – 41

During the next few years the United States Military is going to develop and deploy a highly advanced form of the electronic battlefield. Some parts of this advanced electronic battlefield have already entered combat in S. E. Asia. Other parts have only feasibility study status. Taken in total the outline of a killing machine at least 100 times more efficient than the present “Air War—primitive automated battlefield” can be sketched. The concentrated power of this killing machine will be effectively controlled by the U.S. military alone.

During the next few years the United States Military is going to develop and deploy a highly advanced form of the electronic battlefield. Some parts of this advanced electronic battlefield have already entered combat in S. E. Asia. Other parts have only feasibility study status. Taken in total the outline of a killing machine at least 100 times more efficient than the present “Air War—primitive automated battlefield” can be sketched. The concentrated power of this killing machine will be effectively controlled by the U.S. military alone.

THE AIR WAR

The Air War in Indochina is well known and documented.1, 2 To provide sharper comparison with the new warfare to be introduced in the coming years, I will briefly describe its nature.

With the withdrawal of U.S. ground troops, the U.S. military’s reliance on enormous firepower has come to mean intense air attack. The Air War concedes the ground to the NVA-NLF but attempts stabilization by exerting control from the air. While the U.S. military does not expect victory through airpower, it does expect to prolong the war indefinitely. Airpower is the principle killing instrument which prevents collapse of the weak ARVN forces.

The dynamics of the Air War involve a coordination of the following major components:

Reconnaissance and observation aircraft provide information on the location of ground targets. These include everything from small planes whose pilots depend on eyesight to spot targets, to large jets with multi-sensory equipment (e.g. photographic, infra-red, and radar) whose data is transmitted instantaneously to ground stations for interpretation and targeting.

Bomber and attack aircraft occur in many specialized forms to deliver everything from pinpoint to saturation bombing. A typical bombing mission only requires a pilot to punch in the target coordinates and a computer automatically steers the plane and drops the bombs.

Gunships are flying gun platforms which can fire up to 600 rounds per second. Specifically designed for the S. E. Asian war, they are equipped with multi-sensory devices enabling them to hunt targets at night.

Fixed sensors are immovable sensors (e.g. seismic and acoustic) which are dropped from aircraft over the countryside. The data from the sensors is relayed by communication link aircraft to a distant base where computers assist interpretation, correlation, and targeting.

ARVN ground troops are used to locate NV A-NLF forces so that air and artillery strikes can do the killing. Sometimes ARVN is used as bait to bring NVA-NLF forces into the open. ARVN bases also employ fixed sensors and portable radar for protection against surprise attack.

Integration of these components is the basis of the current Air War. Fixed sensors detect traffic on a section of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and a gunship is directed to hunt down the trucks… Or a reconnaissance jet picks up suspicious multisensory data from a jungle area and B-52s are directed to saturate that area… And so on.

The principal differences between the present Air War and the preceding Ground War are the heavy reliance on aircraft, widespread use of a great variety of sensors, and the computerization of many operations. Without U. S. combat troops the Air War is strategically a defensive war for the U.S. While stationary targets can be attacked, mobile NV ANLF forces cannot be detected and tracked well enough to be targeted. When NVA-NLF forces choose to attack ARVN forces, the NVA-NLF in turn become subject to air attack. However when the NVA-NLF choose to break off battle, there is nothing that effectively pursues them. In general ARVN is not an offensive weapon. The awesome “Lunarizatiort” of Indochina by the Air War merely shows its ability to destroy landscape not the NVA-NLF forces.

AFTER THE AIR WAR

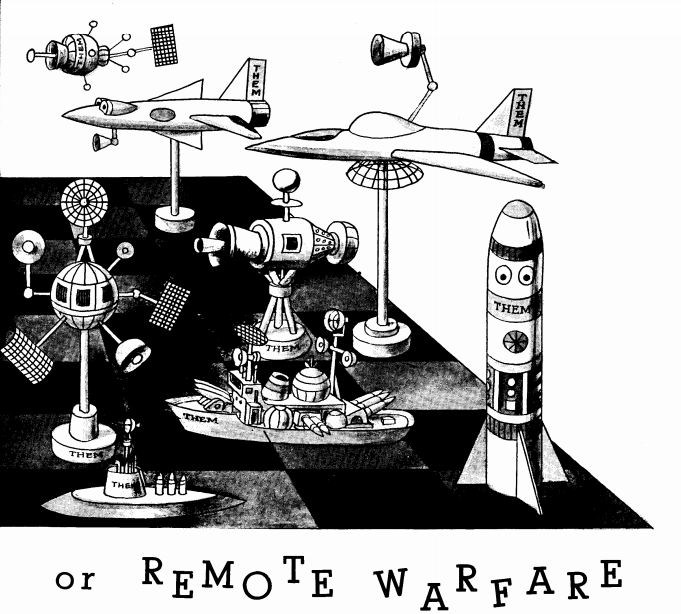

After the Air War a new form of warfare will appear much as the Air War succeeded the Ground War. We can call it the Remote War. Because only a few components are fully operational now and the rest range from initial combat testing to mere feasibility study status, detailed description of the mechanics of Remote War cannot be given now. However enough information is available to sketch out the major components, dynamics, capabilities, and implications of Remote Warfare.

The central concept to Remote War is the remotely manned system, abbreviated RMS, which usually includes a remotely manned vehicle, RMV. The vehicle operator is located at a distant site and presented with information from sensors in the vehicle itself. With this data the operator uses the vehicle control set to send steering signals back to the vehicle. For example, the vehicle might be an aircraft; the sensor, a TV camera; the data display, a TV screen; and the operator would be an aircraft pilot. In the specific, important case in which the vehicle is an aircraft, the abbreviation RPV is used for remotely piloted vehicle. In principle any combination of vehicle and sensor can be used to make a remotely manned vehicle. The concept is to remove the human body from the vehicle yet create a sensory illusion that the vehicle operator is in the vehicle.

The communication links between the RMV and operator are critically important. Because signal transmission is limited to line-of-sight distances (unless cables are used), direct remote control is limited to short ranges. For this reason, airborne communication links are the most important means of controlling RMVs. A series of RPV signal relayers can obtain out-of-sight and over-the-horizon remote control. Satellite communication links are also possible. However the finite velocity of light (and other signals) create a time delay between vehicle and controller, setting a maximum range to feasible remote control. For a 1/16 sec delay this maximum range is a radius of roughly ¼ the earth’s circumference; i.e., a single base can exert remote control over half the earth’s surface.

Engineering requirements for an RMV are drastically simpler than those for a manned vehicle. The absence of human body limitations allows the vehicle to be designed solely from the consideration of machine limitation. For example, there is no limit to how small RMVs can be made other than the current state of electronic miniaturization. RPVs can be incredibly maneuverable since there is no pilot to blackout under too high accelerations. RMVs can be manufactured cheaply because much of the expensive electronic blackboxes are removed with the human (and life support equipment) to the remote control site and the RMV itself does not need the costly human safety tolerances. In fact, for many types of RPVs, air frames may be stamped out of plastic as in toy manufacturing.

Remotely manned systems have penetrated many different environments. Robot-like RMVs walk on land or work in factories.3 RMVs can operate in space with space shuttles and space stations.4 They have already served as planetary rover vehicles on the moon.5 Using communication cables, RMVs function underwater.6 However, the need for simple, line-of-sight communication links mean that the aircraft is the most important vehicle for an RMS. For this reason in Remote Warfare RPVs are the most effective form of RMV.

Dynamics of the Remote War involve a coordination of the following major components:

Reconnaissance RPVs are operational both in S. E. Asia and the Middle East.7 A particularly revealing picture is that taken from an RPV flying under power transmission lines while on reconnaissance over North Vietnam.8 Because of their cheapness and lack of onboard pilot, recon RPVs are able to perform much higher risk missions than comparable manned recon aircraft. Thus SR-71 (the manned recon jet replacing the U-2) flights over China were stopped during Nixon’s visit while unmanned flights were not.9

Reconnaissance RPVs were derived from drone recon and/ or target aircraft.10 Precisely speaking, a drone aircraft is unmanned but lacks vehicle originated, sensory data presentation to a remote pilot. A drone can be tracked using a control site based radar and directed with radio signals, or it can be internally programmed for a specific flight pattern. Since a drone is already unmanned, conversion to remote pilot is relatively easy. There are at least 15 different recon drone aircraft. many of which are also produced in the RPV version.11 Recon drones were operational even before Gary Powers’ U-2 went down over Russia. Their major manufacturers are Teledyne Ryan Aeronautical, San Diego, California Northrop Corporation of Northrup Ventura, Newbury Park, California, and Beech Aircraft Corporation, Wichita, Kansas. Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) RPV s actively assist anti-aircraft defenses, based on electronic intelligence data gathered by recon RPVs. An example of an ECM-RPV (and/or drone) is the Teledyne Ryan AQM-34H. This vehicle carries chaff dispensing pods to sow air corridors of radar-reflecting chaff. In essence these are flight lanes that strike aircraft may take to targets remaining immune to radar directed weapons. This specific ECM technique using an RPV is operational and presumably employed against North Vietnam.12 In addition to chaff dispensers, the AQM-34H is also capable of carrying other kinds of ECM pods. Bomber RPVs are those that deliver air-to-groundweapons. Many combinations of RPV and air-to-ground weapons are possible, including guided weapons. TV-guided bombs and missiles are themselves an expendable “Kamikaze” RMV and work on exactly the same principles. For example, the Hobo TV-guided bomb is a glider RMV; the Condor TV missile, a rocket RMV. Though guided weapons cost more apiece than unguided weapons, they are much more efficient. While half the unguided bombs typically hit within 250 feet of a target, half the guided bombs hit within 5 feet of the target. A single guided bomb effectively replaces 100 unguided bombs. Guided bombs are being used extensively against North Vietnam by manned bombers. Laser Designator (LD) RPVs illuminate targets for attack by laser guided weapons. Laser guided weapons home in on the laser light reflected off of the illuminate target. Laser guided weapons are simpler and cheaper than TV-guided weapons. This simplicity allows construction of laser guided artillery projectiles (which cannot be TV-guided) as well as bombs and missiles.16 Bomber RPVs can carry laser designators and laser guided weapons. An example is the Gyrodyne QH-50D remotely piloted heliocopter.17 The QH-50D uses low-light-level TV and other sensors. Designed to destroy night truck traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail with laser guided rockets, the QH-50D has been built and tested, but we have found no mention of its combat deployment. LD-RPVs are unarmed RPVs which direct weapons delivered by other means. Since it carries only a laser finder/designator besides its sensors, the LD-RPV can be quite small and inexpensive. Long range artillery would be automatically slaved to aim wherever the LD-RPV points its TV and laser. When the remote pilot sees a target on his TV screen, he pushes a button and a laser guided artillery shell destroys the target. The LD-RPV has a study status with the U.S. Army.18 It is to weigh about 300 lbs, fly at 60 mph for 7 to 8 hours and be so small as to be undetectable beyond 3000 feet to the naked eye. Miniaturized (Mini) RPV is a concept under investigation by the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency.19 The goal is to make the RPV as small and inexpensive as possible. The Mini-RPV is a flying sensor and compliments the fixed sensor of the present automated battlefield. Unlike fixed sensors which are basically defensive, the Mini-RPV is offensive. It is designed to hunt targets at very low altitudes. Potentially it has the ability to replace an infantry ground patrol. How small Mini-RPVs can be made depends on the current state of electronic miniaturization. For example, RCA has built a TV camera weighing 1 lb.20 This camera would make possible an RPV weighing about 30 lb, already 1/10 the size of the very small LD-RPV. Fighter RPVs are at the opposite end of the cost-complexity scale from Mini-RPVs. Fighter RPVs are designed for air-to-air combat against manned aircraft. Fighter RPVs can make extremely tight turns which would crush an onboard pilot. This extreme maneuverability alone is capable of obsoleting manned fighters. However, fighter RPVs are necessarily the most complex of RPV types and will take considerably longer to develop. The USAF emphasizes the bomber RPV as opposed to the fighter.21

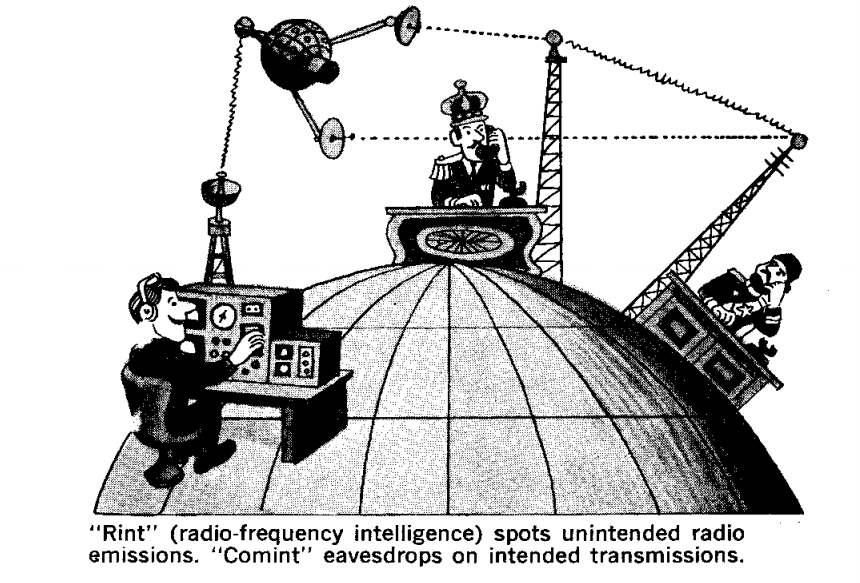

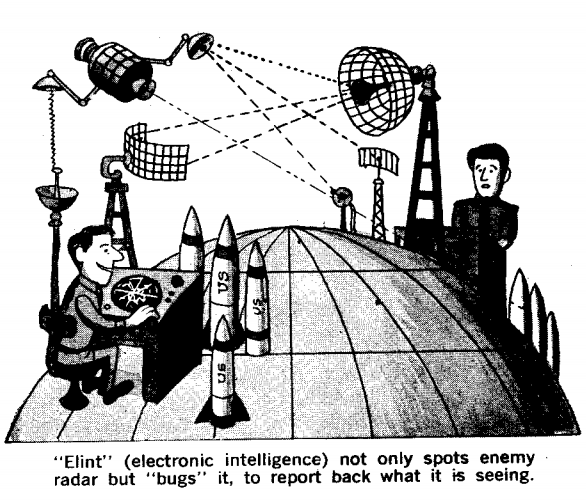

Finally we can sketch the Computer and Communication components of Remote Warfare. Remote War depends on a large capacity for data transmission and processing. This capacity already exists and the development of Remote War involves more an integration of already existent capabilities than research into new ones. Intrinsically, Remote War is much more automated than the present Air War. An example is the computer assisted remote pilot. A digital computer performs the routine flight control of many RPVs enabling a single remote pilot to direct 5 RPV s simultaneously. Univac Division of Sperry Rand, who also manufactures the UPQ-3 microwave (communication link) command guidance system for RPVs,22 is developing the computer assisted remote pilot.23 A representative piece of communication equipment is the phased-array antenna being developed by the USAF Rome Air Development Center to send steering data to 25 RPVs simultaneously as well as providing 5 TV channel communication links.23

The dynamics of Remote Warfare involve the coordination of components to achieve an objective. The present USAF interest emphasizes defense suppression, i.e., to destroy Soviet built air defenses. 24 This is a plan to punch holes through Soviet air defense belts such as exist along the Suez Canal where overlapping radar, anti-aircraft guns, SA-2, SA-3 and SA-4 missiles make conventional air attack very costly. The scenario is roughly the following: Recon RPVs gather data on targets and air defenses. ECM-RPVs then confuse the air defense sensors. Next bomber RPVs attack the anti-aircraft weapons, sensors and control centers. Finally, manned bombers (assuming still some use for them) fly in and attack all the defenseless targets. When the objective is suppression of a Third World guerilla war another scenario can be sketched. Mini-RPVs, acting as flying eyes (also other sensors), silently search the jungle at literally tree top level. With an invulnerability, efficiency and tirelessness unmatched by any human patrol, however dedicated, the Mini-RPVs would hunt down guerrilla forces. Having located and tracked the guerrillas, an LD-RPV would be dispatched to direct guided artillery shells. If the guerrillas were outside artillery range, bomber RPVs would come with air-to-ground weapons. As seen in this sketch, Remote War is fundamentally offensive as opposed to the defensive nature of the current automated battlefield. Defense against Remote Warfare is exceedingly difficult. Guerrillas would be faced with trying to avoid detection from flying or fixed sensors. No part of the jungle would be immune to search from Mini-RPVs. Booby traps or ambushes, so effective against infantry patrols, will not work. Guerrillas will be hard put to even know when they are being observed by Mini-RPVs. The untested extrapolation is that Remote Warfare will deny guerrilla forces concealment in the countryside. Such a loss of jungle sanctuary would spell the end of country-based guerrilla movements. A corollary to suppression of rural guerrilla wars, is that of urban guerrilla wars. It is easy to imagine the following scenario: In the small areas of the cities, fixed security TVs (and other sensors) could be densely placed and used in close conjunction with mini-RPVs and other RMVs. City populations would be required to wear identification which can be sensed and tracked at a distance via these security sensors. This is probable unless techniques are developed which automatically discriminate specific individuals via sensors without the requisite of them wearing identification. Remote War applied to the city would again deny the guerrilla concealment, in this case, among masses of people. Active defense against RPVs with conventional antiaircraft (AA) weapons is unlikely to be effective. Conventional AA weapons are designed against manned aircraft and have only limited value against RPV s which are from one tenth to one thousandth the size and cost of manned aucraft. The small size and great manuverability make RPVs quite difficult to detect or hit. The low cost means quite possibly that the AA weapon costs more than the RPV. For these kinds of reasons the USAF is specifically designing RPVs to attack air defence systems. The extrapolation which is just beginning to be tested is that conventional AA weapons are targets for RPVs, not vice versa. This is not to imply that remote pilot bases cannot be attacked or the communication links jammed in some manner. However, the bases will always be far away and protected by RPVs. Jamming the line-of-sight communication links requires highly sophisticated technical ability and is a partial solution at best. RPVs can switch to a return-to-home mode of internal guidance, to forestall crashing if their external guidance link is broken. A weapon system which in principle can stop RPV attack is the laser thermal weapon. A laser with a continuous output of roughly one megawatt can destroy targets several miles away by vaporizing holes through them. The laser would not be defeated by the RPV’s smallness, low cost or great maneuverability. Funding for such a laser prototype weapon is expected within a year.25 However, unlike RPVs, ray weapons are founded on very new or beyond the state of-the-art technology. Ray weapons are not expected in wide-spread usage for a decade while RPVs are in service now. In the next few years the U.S. military is going to finish developing and deploying the Remote War against which there is no effective (non-nuclear) defense. Any defense where the permanent physical limitations of the human body or machines physically connected with the human body are pitted against machines limited only by purely mechanical constraints, and yet controlled by a remote director, are doomed. Remote War is a war of human machines against the human body. It is as if the human spirit has decided to inhabit machines for the express purpose of destroying the human body. This is not to imply that Remote Warfare is automatically 100% efficient. The first generation are mostly converted-drone recon aircraft and are not specifically designed for Remote War. They have very limited objectives and will not be wholly successful. The second generation will appear much quicker than a corresponding generation of manned aircraft because RPVs are much simpler to develop than manned aircraft. The “Constant Angel” ECM-RPV is a second generation RPV which is to be produced in either a $20,000 expendable or a $50,000 recoverable model. It is so simple to make that the USAF has asked for production bids from 50 manufacturers (instead of a normal 5 for manned aircraft) including several toy companies.26 The second generation will have much greater efficiency, more sweeping objectives,… and so on, through the generations. In principle, Remote War will defeat the human body. One side loses people; the other side loses toys. All that is left is the shooting and dying… and toys don’t die. The economic and psychological characteristics of Remote War determine its ultimate controller. Economically, the Remote War is much cheaper than the Air War besides being more effective. There are no large supply problems because there are few people, spare parts or ammunition requirements. Thus, 500 RPVs can be directed by 100 computer assisted remote pilots. Maintenance of the relatively simple RPVs would be highly automated. There would be no saturation bombing or artillery barrages. With guided ordinance, targets are “surgically” killed by single rounds. In principle, there need be no manned aircraft or ground troops, which drastically cuts cost. In comparison with the present Air War in S.E. Asia, a Remote War would cost (estimation) one one hundredth as much. A large scale Remote War would cost in the 100’s of millions not 10’s of billions of dollars. This relatively small cost is crucial in deciding who controls Remote Wars. Because of this small cost, the U.S. Congress will have no realistic economic restraint over the U.S. military’s conduct of Remote Wars. In practice, the “power of the purse string” of the U.S. Congress over the defense budget does not control sums as small as 100’s of millions of dollars. With respect to the U.S. Congress, this leaves the U.S. Military free to wage Remote Wars wherever and whenever it chooses. This free hand allows the U.S. Military (or the CIA, for that matter) to expand the American empire’s sphere of influence by forcibly crushing national movements which are considered against American interests. The psychological characteristics of Remote Warfare also determine its ultimate controller. Television warriors are numbered in 1,000’s, not the 100,000’s of the Air War. The television warriors never face the prospect of being killed in action. If the Air War over Laos could go on for years without Congressional knowledge, if air strikes could go on for months over North Vietnam without presidential knowledge, then Remote Wars will remain rumors. Presidents and Congresses, wherever they might express opposition, can be kept uninformed. Psychologically, Remote Wars are easy to conceal and the U.S. Military has to tell no one. Characteristics of Remote Warfare could be used to silence anti-war critics who try to stop its development. There will be no American killed-in-action or prisoners-of-war. Toys have no mothers or wives to protest their loss. Remote War is very cheap. Economic critics of war-induced expenses and inflation will have nothing to protest. With its precision killing ability, Remote War will not harm the ecology. Ecologists who complain of environmental devastation will have nothing to protest… and so on. The only thing left to protest is the killing and subjugation of any people the U.S. Military calls “Communists”, “Gooks”,… “the Enemy”. Of course, in principle, the entire world is a potential enemy to the U.S. Military. The U.S.S.R. will shortly face an aggressively expanding American Military Empire. The U.S.S.R. can build its own RMs for Remote Warfare. However, they are substantially behind the U.S. in the important areas of electronic miniaturization and data processing. For instance, the U.S.S.R. is from 5 to 7 years behind the U.S. in general data processing.27 This means the U.S.S.R. version of Remote War will be years behind the U.S. version both in deployment and capabilities. The U.S.S.R. itself will be protected by its nuclear weapons until it develops its own RMs. But until it deploys its own Remote War, the Russian Empire will be vulnerable. What happens when two remote warfare systems oppose each other is basically conjecture. However, several important observations can be made. Until now the description of Remote War has been limited to RMS’s vs. conventional warfare systems. This description is considerably altered for RMS vs. RMS combat. For example, the great cost savings, mentioned earlier, now disappear. If anything, RMS vs. RMS combat will be more expensive than previous completely conventional warfare. In Total Remote War industry can much more directly be converted to war production. The ease of manufacturing RMV’s means that many more will be produced. Tn Total Remote War, as in any war of nearly equal antagonists, both sides are strained to their maximum. A second observation about two opposing remote warfare systems is that a continuous state of war inevitably ensues. In Total Remote War there is no stable equilibrium between reconnaissance and combat. This can be seen for the following reasons: With conventional warfare, peace means, among other things, a continuous intelligence monitoring of the opponent’s military systems. Thus reconnaissance craft actively probe the opponent’s defences trying to get a response. In self-defence the opponent must respond which in turn is monitored by the recon craft to learn how the opponent’s defence work. Naturally enough, the recon craft occaisonally gets destroyed doing such dangerous operations. When the recon craft is manned, its destruction is an international incident which quickly dampens the operations. However, U.S. recon drones have been shot down over Communist nations for over a decade without any international attention.28 Until now this has not led to escalation because one or the other side has not had recon and bomber RPV’s. When both sides have fully equipped remote warfare systems, the delicate difference between a peace time recon probe and actual war dissolves. Recon RPV’s can self-destruct to remove any tangible evidence of their presence. Yet an opponent’s military system can be reduced to a naked helplessness by aggressive RPV recon planes. Without any international incidents to dampen their activities both sides would escalate reconnaissance flights and then, in self-defence, armed recon flights and protective reaction RPV strikes would follow. The difference between war and peace dissolves and War is Peace. Historically, Total Remote War continues the human heritage of war and genocide into a perpetual state of war. For America, as never before, the societal and cultural heritage of an Empire will be turned into a genocide machine. Every aspect of American Industry will play an important production role. Every advance of American Science and Technology will be exploited into greater killing efficiency. All the Western Cowboys and Indians flicks merely become a preconbat primer for the television children. The question of whether violence on TV is harmful to children is now resolved. Where genocide was once recreated on TV for entertainment, it will now be committed with TV. Children who grew up with Vietnam on the TV news at dinner time will surely stomach all the genocide the U.S. Military can produce. The separation of illusion and reality vanishes for the television warriors. Alienation and sterilization approach perfection. After kissing their wives good-bye and battling the rush hour traffic to work, the television warriors will settle down to a day of watching TV at the Ministry of Peace. The tremendous concentration of power which Science and Technology have given the U.S. Military has shattered the checks and balances of power with which the U.S. Constitution tried to protect Americans. Foreign affairs of the American Empire will be run by the U.S. Military Dictatorship. Arms Limitation Treaties, Peace Treaties, and other Agreements, both public and secret, will be signed with other Military Dictatorships. But there will always be war because that is what peace means to the Ministry of Peace. If during peace time a citizen does not support war against the Enemy, then that individual is a subversive. The individual becomes the Enemy. The next step then is to control the internal affairs of Empire … the establishment of a Ministry of Love. Thanks to NEAR (New England Action Research) for “Toys Against the People”. For more information on military R&D contact them at 48 Inman Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139. We chose to print this article on remote warfare for two reasons. First, it increases the technical knowledge of those working against the war, making our actions more well-informed and hopefully, more effective. Second, it paints a convincing picture of the military-political thinking current among those who rule this country. We do not, however, share the article’s apocalyptic vision, nor its assumption of the ultimate superiority of those who control the most advanced technology. Since we believe that the pessimistic and awe-stricken views presented in the article are essentially due to a lack of proper political perspective we are presenting our analysis of the place and significance of the remote war technology within the American Reich. First it must be pointed out that the development of the remote war technology issues from the weakness, not strength of American capitalism. In fact, this technology signifies further estrangement of the system from the American people. The Air War was developed because the American Army was no longer trustworthy. Remote warfare will come into being because this war and any future wars waged by the American Imperialists to control the world are no longer politically acceptable to the American people. Just as there has been an increase of social control and surveillance research to deal with resistance and lack of support at home, the American military has had to try to find technological solutions for its political problems. There is nothing new in this. American corporations have repeatedly used technical advances to diminish the power of organized labor. For example, there are numerous cases of increased mechanization or new processes requiring fewer workers directly following (and due to) strikes. This has taken place even when the new processes are less profitable. Second, escalation to complex (and profitable) technology is an endemic feature of American capitalism. In the domain of consumer goods the process of substitution of more complex goods for the simpler ones is a feature so familiar that at times it even escapes our consciousness. Likewise, in the domain of capital goods the evolution of ever more capital intensive technology goes on relentlessly. It is important to perceive these processes freed from their ideological justification. It is not “progress” nor greater efficiency nor better satisfaction of consumers’ needs that drives these processes. In the background there always looms the system’s need for expansion, for operations on ever larger profits. The Remote War is an application of the same principle to another industry, the war industry. There are a few other points in the article that deserve some comment. First, there is little indication that the new technology will result in a lower “defense” budget. What is more likely is that the successive levels of war technology will coexist side by side, much as the missiles and the bombers do. Then there is the question of invincibility, the superhuman precision, the omniscience of sensors loaded on pilotless RPV’s hooked to computer networks … etc. For those who are impressed by these claims we recommend paying attention to similar claims made in the past. There exists a vast difference between the results obtained under controlled conditions and the actual battle conditions. For most parts, the results obtained by the U.S. depend on massive and indiscriminate destruction and this dependence did not diminish in the last thirty years. The image of pinpoint destruction of individual resistors is a false one-saturation bombing has increased with the use of sensors, and there has been no quantum jump in their effectiveness. It must be remembered that in this war, as must be the case in all wars of liberation, bombing is a terror weapon. Its major purpose is to denude the countryside of the actual and potential guerilla supporters, and destroy the traditional social fabric of the country, driving the people into American-dominated cities (providing, incidentally, an excess labor pool). Technology is not invincible. That is a myth which leads to passivity. It is common among scientific workers and represents a kind of technical/intellectual chauvinism. The power for social change lies with the large oppressed segments of society, and it is with them that we must join. — The Editorial Collective  The first operational bomber RPV is believed to have entered combat early this summer in S.E. Asia.13 Presumably it is the 234 class model of the Teledyne Ryan AQM-34L.14 A rough comparison can be drawn between an F-4 Phantom manned bomber and the AQM-34L. The AQM-34L is approximately 4,000 lb and $400,000, 1/10 the weight and cost of the F-4. The AQM-34L carnes 1,000 lb, 1/10 the bomb load of the F-4. Using unguided bombs against ground targets, even theoretical calculations heavily conservative in favor of the F-4 show that the AQM-34L costs only 1/10 as much as the F-4 to destroy the ground target.15 These calculations did not include that the RPV also does not risk aircraft crew as an F-4 would.

The first operational bomber RPV is believed to have entered combat early this summer in S.E. Asia.13 Presumably it is the 234 class model of the Teledyne Ryan AQM-34L.14 A rough comparison can be drawn between an F-4 Phantom manned bomber and the AQM-34L. The AQM-34L is approximately 4,000 lb and $400,000, 1/10 the weight and cost of the F-4. The AQM-34L carnes 1,000 lb, 1/10 the bomb load of the F-4. Using unguided bombs against ground targets, even theoretical calculations heavily conservative in favor of the F-4 show that the AQM-34L costs only 1/10 as much as the F-4 to destroy the ground target.15 These calculations did not include that the RPV also does not risk aircraft crew as an F-4 would.

THE U.S. MILITARY DICTATORSHIP

REMOTE WAR RATIONALE

>> Back to Vol. 5, No. 1 <<

REFERENCES

Project Air War and the Indochina Resource Center, Air War, 1972.