This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Questions from Argentine: Que Pasa en los Estados Unidos?

by Ana Berta Chepelinsky, Marco Saraceno, & Paulo Strigini

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 4, No. 6, November 1972, p. 16 — 18

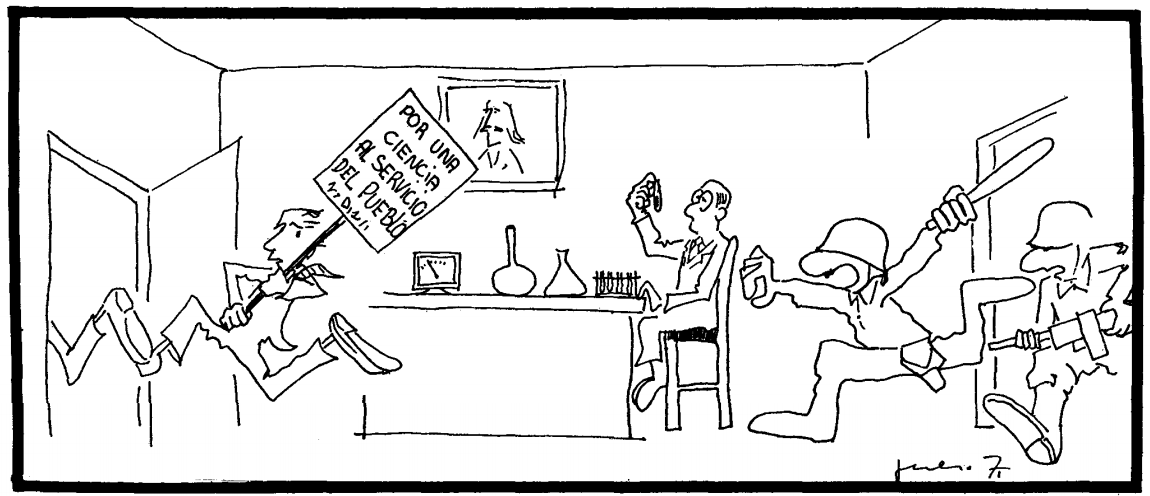

For some time we have exchanged Science for the People with Ciencia Nueva, a magazine published in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Ciencia Nueva’s objective is to bring scientific problems in front of Argentine and other Latin American people. In this way science and technology are confronted with the economic and political decisions related to the development of Latin American Whereas some of these problems emerge—under a particular political perspective—in the pages of magazines like Science, Nature, The New Scientist, nothing comparable exists in Latin America. Instead, a crude censorship and a very direct political repression make it difficult and dangerous even to discuss these problems at all.

Recently, Ciencia Nueva has sent around a questionnaire for Argentines and other Latin Americans and for us to answer, which is printed below.

- Why do you think organizations of scientists engaged in the production of knowledge are necessary? How was your organization started?

- Researchers are mainly wage earners. Why do you think that most of these organizations take a professional attitude rather than a labor union one?

- This process of organizing, among the researchers and those who teach at the university, has recently accelerated. Why? Does a division exist between these groups in our country?

- Do you think scientists’ organizations should participate in social and economic decision making, particularly in relation to their scientific activity?

- Scientific workers face many problems. Which ones are the most serious and important?

- What do you think about the functions and activities of CONACYT? 1

- The university is a place of creation and generation of knowledge. What is your position in connection to the problems of the development of the universities?

- Have private universities carried out these functions? Are the new plans for development and foundation of universities correct?

- What do you think about the plans for large multidisciplinary research facilities like the Castelar project?2

- Do you deem desirable that researchers’ associations (both existing and future ones) federate? Why? If yes, which form should the federation of the scientific associations take?

The problems created by science and technology are not confined within any national boundary. The effort to extricate them from their political and economic ties and to use them as a liberating force to serve the needs of the people, results in an international brotherhood, what some would call an international conspiracy. Argentine scientists are asking themselves, as we are, to what kind of science people’s efforts and the country’s resources should be devoted. Although their political principles may be similar to those of many scientists in this country, the form their questions take is in some cases different. These differences are interesting, because they are related to the different degree of development of science and technology as a productive force and to the different social and political context in which scientists operate. The brief comments below will try to sketch and analyze some major differences.

Several questions asked by Ciencia Nueva deal with the form of scientists’ organizations. A trend to transform traditional academic associations like ACS, APS, etc. into professional guilds like the AMA is visible in the United States. Many are opposed to this trend for various reasons. Sometimes the choice between a professional and a union type of organization presents itself as a choice of the lesser evil. In the U.S. context this choice involves two aspects: (1) the form of the struggle that scientists are prepared for, for instance, shall we go on strike? (2) the content of our demands, how we can go beyond the concern for our economic welfare and security? It appears controversial to many scientists and technicians in this country in industry and in the university which type of organization may be more effective at a political level. However, the examples of the women’s and the student movements suggest that some entirely new forms of organization are necessary, although it is also evident they have shortcomings.

In Argentina trade unions are involved in a years long struggle which is not confined to economic demands, but is part of a general political confrontation. The reasons for this militant unionism are both economic and political. On one hand, average salaries are below the subsistence level; on the other the company owner is often a foreign corporation or the state itself. The Argentine university also belongs to the state. Therefore, one may expect a scientists’ union in the university and in industry not only to be more militant, but also to take a position over the political control of science and technology. However, some experiments in this sense in Italy and France have been criticized as inadequate to spread the limited privileges of the scientists (their relative freedom in their laboratories and offices) to the other workers, even within the same union, so that the goal of a real and general workers control over all kinds of production, including science, is not attained anywhere. The struggle to achieve this goal in Argentina (and in part of capitalist Europe) is a direct confrontation with the state.

It is probably to evade this direct confrontation—and the students’ rebellion—that private universities and research institutions are blooming lately in Buenos Aires, the city where one third of all the Argentine people live. These private institutions are funded mainly with foreign money, through the local branch of the World Bank and U.S. foundations. They are administered according to the U.S. model, rather than as a special section of the public administration. They are planned as the school for the middle managers, professionals and technicians. They hope to become the only school for the local middle class, should the deterioration of the state university, due to political repression, continue for the worse. As for the Argentinian elite, there is traditionally a college in Europe or, more recently, in the U.S.

| Ciencia Nueva explains its position in the editorial of its first issue (April 1970):…Two-thirds of humanity live in desperate conditions with regard to food, shelter and education. The other third is forced to consume indiscriminately in order to keep the economy of their country going. Only a tiny minority has access to decisions concerning the goals of science, economy and culture. In that sense, the great majority of Argentinians and Latin-Americans belong to that part of the world that has no possibilities—yet—to determine which are its own interests and find solutions to its own problems. Humanity has today the technological and scientific resources to end its most pressing inequalities. However, the great concentration of political and economic power in the hands of small privileged groups has as a result that these resources are used only for the benefit of the elites of power. Thus large sectors suffer today more misery and deprivation than at any other time in history. This divorce between the consequences of science and the interests of workers makes deeper the breach between the scientific worker and the rest of society… …We need an organization of scientific research which stresses the fulfillment of the needs of social groups that are today exploited and oppressed. It will certainly produce a body of results in mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology and medicine rather different from the kind of science we know today. However this will only be possible with the full participation of these oppressed groups. Science is not the only place, and by no means the most important one, where the struggle for the fulfillment of our needs takes place. But it is another place where our presence—critical towards the past evolution, constructive with regard to the roads we want opened—is necessary if we want to start making decisions about our own future. Ciencia Nueva wants to be a forum for discussion, a place where we can resort to mature criticism to judge and decide what kind of science we need. We also want to report on current scientific activity in Argentina, Latin-America and the world. However we do not want to be another popular science magazine, i.e., to present a passive spectator with the results of research done elsewhere and inaccessible to discussion, as if science was to be shown finished to the non-expert. Our pages belong to all those who with to engage in this discussion. For information write: Ciencia Nueva |

Another aspect which appears in Ciencia Nueva’s questions is some trend to plan the scientific and technological development of Argentina (CONACYT)3 and to create the infrastructure for such development in the form large interlocked research institutions (project Castelar5). Such things (NSF, R&D, the large research centers) have existed for many years in this country. The seem to be plunging into a deepening crisis, since they cannot solve the contradictions between social needs and capitalist profits. Very few politically conscious people here want more of that science and technology: in the third world that science and technology are the only existent model that they can build upon, short of socialist revolution. Moreover, there is no convincing model for what science and technology should be in a technically advanced socialist society.

The productive forces in the U.S. and elsewhere—altogether in ¼ of the world—have reached such a development that science and technology are an indispensable part of the economy. Although many scientists and technicians don’t see themselves as workers—neither in the university nor in industry—their privileges with respect to other workers are limited. In the rest of the world these privileges are relatively larger and the relevance of their work to the economy of their countries is much less clear. Therefore the alienation of the Argentinian scientist is deeper: not only she or he does not control the use of her/his work, but this work is actually of very little use for the society as it is. In these conditions, a plan of economic development which provides a place for the application of scientific research, is a primary necessity. In its absence, the third world scientist is actually working for the U.S. in conditions of special economic and cultural dependence. Economic, because her/his work is likely to be useful in the U.S., the largest technological empire in the world, however her/his salary is not as high there as it is here. Cultural, because the specific language, the research context and the institutions of modern science, as they exist in the U.S., represent an unattainable goal and a powerful attraction.

Finally, we can see where the struggle of scientists and other workers in different societies cultures may converge. A real program of scientific and economic change—a program of science for all the people—is also needed in this country. But it is possible only in a socialist society, where the contradictions between the goals and the uses of science and technology, between the immediate and long- range interests of different social groups, can be solved without oppression and exploitation.

Some of Ciencia Nueva’s questions may appear naive, misplaced or not at all understandable to U.S. scientific workers. We hope our comments may help understanding them better. In any case we think it useful for Ciencia Nueva and for us, to confront ideas and questions which come from the two ends of this continent. We invite all our readers to think and comment on them the way they prefer and to send us their answers. We plan to compare these answers to those that Ciencia Nueva is gathering from Argentinian and other Latin American fellow scientists. This plan may be a first step in our preparation for the scientific establishment’s imperial meeting in Ciudad de Mexico (AAA$, Mexico City, June 1973).

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 6 <<

NOTES

- CONACYT (National Council of Science and Technology). It’s a bureaucratic institution created in 1968 by the military dictatorship, to make a study of the present situation of science and technology in the country and of its potential for development. So far, the study has just collected a lot of data which isn’t being used to formulate any scientific and technological policy in accordance to the national reality.

- Castelar project is a plan to create a huge research institution in the Buenos Aires area. It was born in the CONICET (National Scientific and Technological Research Council of Argentina). The is being done in a climate of secrecy, without allowing scientists to participate in it. There are foreign loans involved (from Bank of Development). It is a very ambitious project which doesn’t take into account the priorities of the Argentine reality.

- CONACYT (National Council of Science and Technology). It’s a bureaucratic institution created in 1968 by the military dictatorship, to make a study of the present situation of science and technology in the country and of its potential for development. So far, the study has just collected a lot of data which isn’t being used to formulate any scientific and technological policy in accordance to the national reality.

- 4Castelar project is a plan to create a huge research institution in the Buenos Aires area. It was born in the CONICET (National Scientific and Technological Research Council of Argentina). The is being done in a climate of secrecy, without allowing scientists to participate in it. There are foreign loans involved (from Bank of Development). It is a very ambitious project which doesn’t take into account the priorities of the Argentine reality.