This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Our Bodies, Our Selves: A Review

by George Salzman

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 4, No. 3, May 1972, p. 18 – 20

OUR BODIES OUR SELVES1 strikes out against the myths about women that help maintain the position of women in this society. For example, there is the myth that the basic social and psychological needs of women are determined solely by internal forces, that is, by their biological inheritance. The ideology that oppresses women manifests itself in almost every institution of American society and every avenue of American life, from the schools which assume that young women are more suited (psychologically, of course) to study nursing than medicine, to the cosmetic advertising which frightens them with visions of a life barren of sexual fulfillment if anyone but their hairdresser knows for sure.

The oppressive set of myths that make up a large part of this ideology can survive only so long as women remain ignorant of their physiology, of the commonness of their psychological suffering, and of the role that the ideology itself plays in influencing them to accept their oppression (indeed in often preventing them from even being aware of its existence). Our Bodies Our Selves has an impressive amount of basic information about women’s bodies. It also talks about the pressures of society on women—but not through laboratory studies. We read the personal experiences of many individual women.

But it does much more than merely to provide information. Liberal muckrakers are forever providing dismal information, exposing corruption, brutality, calculated lying by high government officials, etc., etc.,—leaving their readers overwhelmed by how bad it all is, how hopeless, and despairing of any possibility for bettering life, and succumbing eventually to cynicism. This book leads women not to despair, but to feel pride in themselves as autonomous human beings, to experience a sense of unity with each other, and to realize the potential for revolutionary social change that their coming together will provide. It helps each of us take the first step in building this unity—that of learning about ourselves and each other, and the rich possibilities inherent in working together.

It was in the struggle against their own oppression that a group of ordinary women created this extraordinary book. Our Bodies Our Selves is extraordinary not only because it is excellent—though that alone would give it unusual status—but because it was not authored by an “outstanding” woman doctor or physiologist. In fact, it is unlikely that it could have been written by any one person. It is based upon the experiences of many women, and was created by the collective effort of about two dozen of them, the members of the Boston Women’s Health Course Collective, hereafter called the Health Collective. They describe the book as “a course by and for women.”

Possibly even more important than the content of the book is the process by which it was made (a process that the book illuminates very well) and the fact that its authors included no experts, no specialists, no professionals. Elite professionals (i.e. most professionals) would regard them as “unqualified” for the job, for it was no minor task to tackle the body of knowledge they sought (and still seek) to encompass in their work. To realize that ordinary people can demystify knowledge and use it as a tool for liberation is to see the revolutionary power that lies in each of us. And this vision is itself a potent force. It unleashes our energies as nothing else can because it is a vision of totally unalienated labor. It inspires us to join the process. The authors describe that first awareness, (p.1)

Possibly even more important than the content of the book is the process by which it was made (a process that the book illuminates very well) and the fact that its authors included no experts, no specialists, no professionals. Elite professionals (i.e. most professionals) would regard them as “unqualified” for the job, for it was no minor task to tackle the body of knowledge they sought (and still seek) to encompass in their work. To realize that ordinary people can demystify knowledge and use it as a tool for liberation is to see the revolutionary power that lies in each of us. And this vision is itself a potent force. It unleashes our energies as nothing else can because it is a vision of totally unalienated labor. It inspires us to join the process. The authors describe that first awareness, (p.1)

… several of us developed a questionnaire about women’s feelings about their bodies and their relationship to doctors. We discovered there were no “good” doctors and we had to learn for ourselves. We talked about our own experiences and we shared our own knowledge. We went to books and to medically trained people for more information. We picked… [topics] we wanted to do and worked individually and in groups to write the papers. The process that developed in the group became as important as the material we were learning. For the first time, we were doing research and writing papers that were about us and for us. We were excited and our excitement was powerful. We wanted to share both the excitement and the material we were learning with our sisters. We saw ourselves differently and our lives began to change. (Emphases added.)

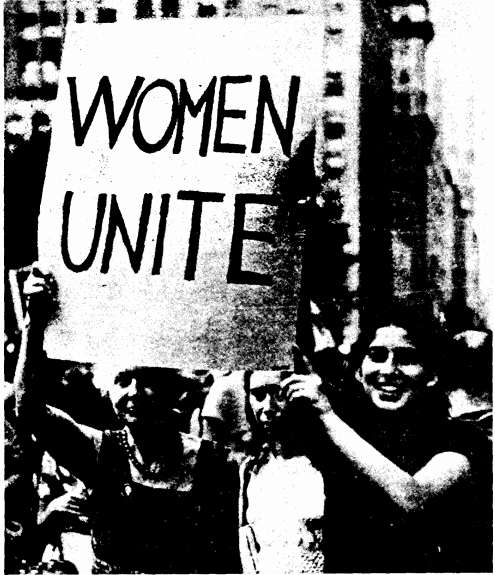

Their book is an exemplary movement effort in many ways. The price, 30 cents or less, has nothing to do with its intrinsic value to people, but reflects rather its cost of production. The cost was held minimal by making the book strictly utilitarian. One hundred and forty pages of newsprint, roughly 8 and 1/2 by 11 inches, bound together by three heavy staples, with the cover also newsprint, it is not a technical masterpiece—not a book you can be “proud to own.” Its spirit is symbolized by the photograph on the cover of three women, one of whom is under 16 years of age, another of whom is over 60, holding a hand-lettered sign that says simply, “WOMEN UNITE.” Alive with the women who wrote it, it is always compassionate. Unquestionable is the total honesty of the women authors with each other—and with us. One finds no semantic tricks, no jargon, no aping of academics, no euphemisms. Deprivation is called “deprivation”, not “underprivilege”.

Moreover, the clarity of their political and social analysis is not lessened by the bitterness of personal experiences. Doctors are a case in point. A woman (or man) in need of a doctor’s attention is particularly vulnerable; is at the mercy of the doctor in whose hands she places herself for treatment. Again and again doctors, almost all of whom are male, are criticized: for their dehumanizing treatment of women as objects instead of people, for their ritualistic lack of candor with the patient, for their assembly-line methods, for their avarice—in short, for making the Hippocratic oath into a hypocritic oath by the conduct of their professional lives. The women correctly see doctors as a class of people who oppress them, yet to their credit they also see doctors as individual victims of the social order: (p. 65)

The individual doctor does not break out of the system because he has been forced to work hard for sub-standard pay for many years, and just as he starts to make more money, which he has come to think is his due, he doesn’t dare risk his job by performing abortions or by urging his hospital to allow more of them.

And later on, (pp. 128-129)

Doctors are doctor chauvinists as well as male chauvinists… Medical schools teach their students… to occupy an exalted position in the medical world (and society in general)… Doctors go through a greater socializing process than even the priesthood. For at least seven years they spend most of their waking hours not only absorbing medical information, but learning how to act and think as well. Thus the social order… is established.

Medical schools are maintained as elitist institutions by their high tuition and the almost total lack of federal aid for scholarships to medical schools… The students are mainly from well-off families… The AMA [American Medical Association] has fought hard to maintain this status quo.

The ability to distinguish among one’s oppressors, and to understand which of them are themselves victims of the social structure, is an important part of revolutionary consciousness.

Nor are men seen as enemies. The authors are not out to teach men or to “trade places” with them. In one of the very rare passages (perhaps the only one) directed to men, they write: (p. 24)

To any men who happen to read this: This pamphlet was not written for you… please do not suggest to your girl that she read it. If you want to change your behavior and you are living together, you might start doing half the housework… In the long run you should try to change your own life, and the society, so that you can be pleased with and proud of yourself without having to exploit her. For either of the sexes to be free, both you and she must be leading worthwhile lives…

The goal of this pamphlet, and of the Women’s Liberation movement, is to help us move towards a world in which human relationships can be more free, more satisfying. This means freedom from class and racial oppression, and it means freedom for all from want and from alienating work…

This pamphlet… ought to be the beginning, for us, of a revolution.

The book, for it is more a book than a pamphlet, consists of a brief introduction to the health course, and eleven chapters, each written by one or several of the women in the Health Collective. The chapter titles are: Anatomy and Physiology; Sexuality; Some Myths about Women; Venereal Disease; Birth Control; Abortion; Pregnancy; Prepared Childbirth; Post Partum; Medical Institutions; Women, Medicine, and Capitalism.

The book is crammed with factual information that everyone ought to know. For example, in the twenty-odd years since the Chinese revolution, “syphilis has been completely ended.” (p. 37) “This was done by giving a blood test to almost everybody. Consequently, everyone found to have syphilis was adequately treated and syphilis is no longer a problem.” (p. 34) “What about in the United States? In this country… [there are] about… 300 new cases of syphilis every day. Approximately 4000 people each year die in the late stage of untreated syphilis.” (p. 37)

Thus the book cries out, ALL KNOWLEDGE TO THE PEOPLE! The authors know that knowledge is the prerequisite to the power they need in order to take control of their own lives. And they invite all women to join in their effort—to make the course a living experience for all women—to expand and enrich it by adding each woman’s thoughts and knowledge to theirs. They write: (p. iii)

The first printing sold so fast we haven’t had time to revise the printed course. We are working on revisions which we hope will be ready for the 3rd printing. We want to add chapters on menopause and getting older and attitudes to children (child rearing alternatives, single women having children, adopting, also not having children). We want to expand the existing chapters to include more on monogamy, homosexuality, women’s diseases and hysterectomies, the relation between mental and physical health, nutrition, etc., etc.

Would you like to make suggestions, write up your own experience, or otherwise work on the course? Please write us. The course is what all of us make it.2

In a larger sense, what the book says to us—all of us, women and men—is that our lives are what all of us, collectively, make of them, and that we can, and ought, join together to make them better.

>> Back to Vol. 4, No. 3 <<

NOTES

- Our Bodies Our Selves, a course by and for women. First edition, 5th printing of Women and Their Bodies, March 1972, iv+ 138 pp., prepared by the Boston Women’s Health Course Collective. Available from the New England Free Press, 791 Tremont St., Boston, Mass. 02118. Individual copies $.30+$.15 for postage; 2-9 copies $.30 per copy; 1 0-49 copies $.28 per copy; 50-199 copies $.25 per copy; 200-499 copies $.22 per copy; 500+ copies $.20 per copy; to people distributing copies free $.10 per copy for all copies being distributed free. Price for 2 or more copies includes postage.

- You can write the authors at: Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, Box 192, West Somerville, Mass. 02144.