This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

Science for Human Rights: Using Genetic Screening and Forensic Science to Find Argentina’s Disappeared

by Barbara Beckwith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 19, No. 1, January-February 1987, p. 6-9&32

Barbara Beckwith is a freelance writer and former member of SftP’s Sociobiology Study Group.

Over the course of Argentina’s eight-year military rule, the word “disappeared” took on a new and sinister meaning. It came to mean abducted, tortured, murdered, and most probably buried anonymously in a secret mass grave.

Between 1976 and 1983, a series of military juntas ruled the country, with Army and Air Force generals proclaiming themselves president. The most recent junta’s failed attempt to take over the Falkland Islands from Great Britain forced the junta to resign. Civilian government was restored, and democratic elections voted President Raul Alfonsin into power.

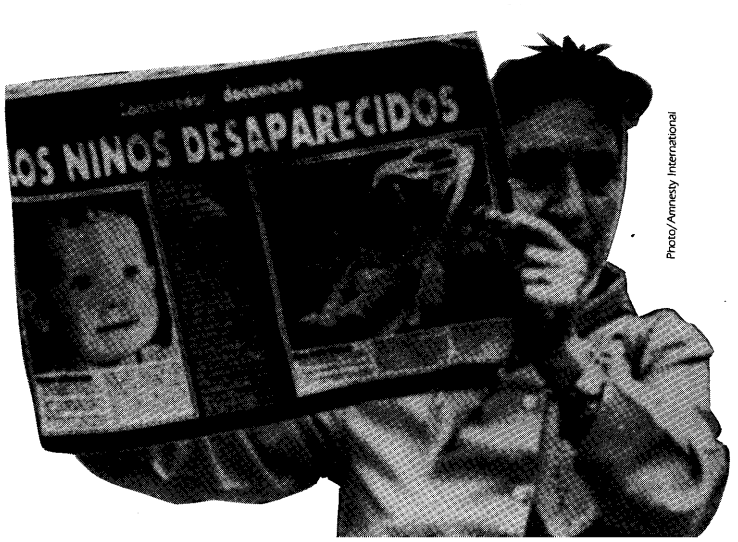

It is estimated that from 9,000 to 25,000 Argentinians disappeared from sight during the juntas’ reign. Some were thrown out of planes into the sea and may never be found—an occasional body washes up on Uruguayan beaches. An unknown number may have escaped to other countries. But it is now clear that the largest number of the missing Argentinians were systematically tortured and murdered by the Argentinian military in one of the worst cases of human rights abuses in history.

“First we will kill the subversives,” one police official announced openly during those dark years. “Then we will kill their collaborators, then their sympathizers, then those who remain indifferent. And then we will kill the timid.”

Between 200 and 400 children are included in the list of “disappeared”—some murdered, some abducted, but most born in prison. The military followed a rule: to wait to kill a pregnant woman prisoner until after she gave birth—but the rule didn’t apply to torture. The newborn children were then sold on the black market, given to adoption agencies, or taken as “war booty” into military families.

“Subversive parents teach their children subversion; this has to be stopped,” explained former Buenos Aires police chief General Ramon Campos in a 1984 interview, recalling how he took children from their parents to give to adoption agencies. Campos is currently in preventive detention on human rights charges.

During the military era, forensic and medical doctors were ordered by the military to falsify birth, medical, and death records to cover up torture, killings, and illegal adoptions of children. Nursing personnel who notified relatives of prison births were at times “disappeared” as well.

Since late 1983, the killing has stopped; democracy is now restored in Argentina. But for the families of the disappeared, the suffering continues: the pain of not being able to bury your child’s body, not knowing if your grandchildren are dead or alive, and realizing that your child’s torturers and murderers are still at large. Many military officers from the former regime remain in their posts, even those scheduled for prosecution.

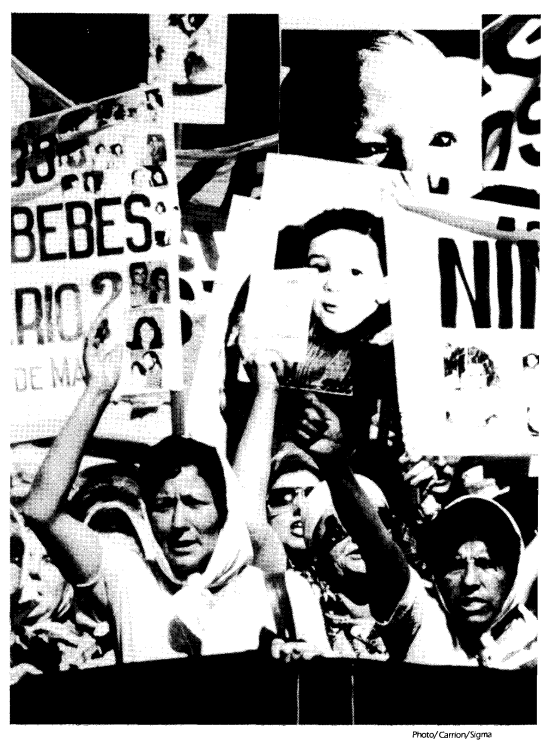

Members of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Madres), a human rights group composed of relatives of the disappeared, continue to demonstrate at the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires every Thursday, as they have since 1977, calling for the return of their children, dead or alive. With them march the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, demanding the identification and return of their kidnapped grandchildren.

The Grandmothers (Abuelas) have spent years trying to track down their missing grandchildren. Using techniques worthy of the best detectives, they scrutinized hospital records for falsified birth certificates, pored over adoption papers, and even posed as maids in military families to gather information on children living in those homes. Of 200 children listed as missing, the Abuelas have now located 39. Four were dead, but the rest are still alive.

But to gain legal custody of children they are convinced are their grandchildren, the Abuelas need more than records and eyewitness accounts. They need concrete evidence of a biological link between themselves and chidren living with adopted families.

The Grandmothers had a hunch that genetics might be the answer. None of them were scientists, but they were intelligent people. They knew about paternity testing; they knew blood tests could prove that a particular set of adults must be the parents of a particular child. But in most cases with which the Abuelas were dealing, both parents had been “disappeared.” How could testing prove a familial link if only the grandparents were living, if the intervening generation were missing? They wondered if genetics might help.

The Investigation Begins

In 1984, two Grandmothers flew to New York City to hear a scientific presentation concerning a purely theoretical formula for determining grandpaternity based on genetic variation in blood samples. They then went on to Washington to talk with Eric Stover of the Committee on Freedom and Responsibility of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). They had one question: was it possible to use genetics to match up relatives two generations apart?

In May 1984, Mary Claire King, professor of epidemiology at the University of California’s School of Public Health in Berkeley, got a call from Stover asking if she knew the answer to the Abuelas’ question. Yes, she said, a genetic grandpaternity test should work—in theory at least. A month later, King was on her way to Buenos Aires to turn theory into fact.

In part, King was motivated by having a daughter the same age as those the Grandmothers were trying to identify. “If I had been born in Buenos Aires, not in Chicago, I probably would have been one of them, and my daughter would have been kidnapped,” says King.

Also on the June trip to Buenos Aires were Stover, geneticist Cristian Orrego, and four forensic specialists, including Clyde Snow (who helped identify the remains of the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele), and Luke Tedeschi, Director of Laboratories at Framingham Union Hospital in Massachusetts. The forensic team went to use their skills to identify skeletons from mass graves of the disappeared, while King worked out methods for identifying their children.

They traveled to Argentina under unprecedented circumstances. Democracy had only been restored for seven months. Already, a National Committee on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADAP) had begun hearing citizens’ testimony on 8,800 illegal abductions. Each locality had its own commission gathering data, and human rights groups were actively involved. The AAAS delegation had been invited by human rights groups (including the Grandmothers), CONADAP, and President Alfonsin.

“In the past, human rights expeditions were clandestine,” says Tedeschi. “This was the first time a human rights investigation was given carte blanche.”

Once in Argentina, King, determined to help Argentinians work out grandpaternity testing rather than doing the testing for them, looked for a laboratory equipped to do genetics. The Mothers rejected one private laboratory because of connections between its staff and the military, the very people responsible for the disappearances. Instead, they sent King to Ana Maria Di Lonardo’s laboratory in Durand Hospital, a general hospital severely neglected by the former military government.

“The place was falling apart—corridors were propped up with wood,” recalls King. “But here was this terrific modern immunology lab—very democratic, very interactive—doing genetic marker paternity testing.” Many of the researchers working in Di Lonardo’s lab had lost relatives and friends during the military regime and were eager to help locate the disappeared.

King spent that day explaining the grandpaternity testing theory to the research group—”They grasped the basic principle in five minutes, and got ahead of me very fast. Soon I was handing the chalk over to them.”

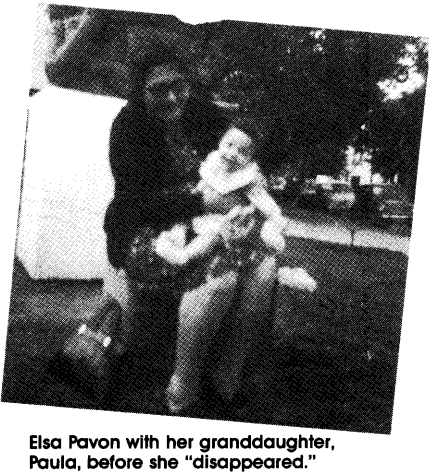

Having taught in Latin America, King supposed that getting the grandpaternity research project going would be a long, involved process. Instead, the Durand researchers told her, “This afternoon, we’ll draw blood from Elsa Pavon (a claimant grandmother) and then we have a court order to draw blood from Paula (a girl living as the natural child of a police officer). We can work in two shifts.”

Between 200 and 400 children are included in the list of “disappeared”- some murdered, some abducted, but most born in prison.

The next morning at 9 AM, the results were in. The data for Elsa Pavon and Paula showed a 99.9 percent probability of grandmaternity. “We didn’t realize ourselves how powerful the testing could be,” King recalls.

A year later, after court proceedings including testimony by the lab group, Paula was legally removed from the home of officer Ruben Lavallen and returned to Pavon, who the court ruled was Paula’s natural grandparent. Lavallen and a physician are being prosecuted for birth certificate forgery.

Paula is the first of 20 children of disappeared Argentinians whose identity has been determined in court on the basis, in part, of genetic tests, as well as evidence and eyewitness accounts produced by the Grandmothers.

From Genetic Markers to Grandpaternity

In effect, the Di Lonardo-King collaboration has extended paternity testing one generation further. In paternity disputes, the blood of a child and that of the man claimed to be the child’s father can be compared. If a relatively rare combination of genetically determined elements is present in both samples, the people in question are most probably father and child.

Grandchildren, however, share only one-fourth of their genetic makeup with their grandparents. But if enough “genetic markers” can be found in the blood of both the child and the petitioning adults, the probability rates will still be high enough to show that the child and adult must be grandchild and grandparent.

The genetic markers used include five blood groups, fifteen different red cell enzymes, and HLA (proteins on the surface of white blood cells which vary significantly between individuals). At the University of California School of Public Health in Berkeley, Cristian Orrego is currently working out procedures for using DNA polymorphisms—sites on the DNA where significant variation can be found among humans—as another type of marker.

Factoring in the known distribution of various markers in the Argentinian population, an “index of grandpaternity” can be figured mathematically. The result has been the establishment of high probabilities—up to 99.9 percent—that shared genetic markers are the result of familial biology, not random chance. All data is tested “blind” to preclude researcher bias.

Figuring an index of grandpaternity in cases where both grandparents are dead is also possible. The Durand lab would first reconstruct the genetic makeup of grandparents from blood samples taken from aunts and uncles, and then work backward to connect the grandparents’ and the grandchild’s genetic makeup. The genetic approach proved powerful even if one or both grandparents had died.

Ironically, genetic testing works both ways. In some instances, it proved that there was no biological relationship between a suspected abducted child and the claimed grandparents.

As grandparents of the missing children of the disappeared grow old and die, identification of disappeared children becomes more difficult. A National Bank of Genetic Data is now being set up to test and keep blood samples of relatives of missing children, so that the chance will remain that their grandchildren can eventually be located and genetically identified.

The gene bank has now tested blood samples of 250 people from 40 to 50 families of the disappeared and their children. “If in the future a child grows up and finds he was kidnapped as a child, he can find out who he is,” says King.

The gene bank will also keep computer disk copies in an unnamed country outside Argentina to preserve all data in case of a coup. “Argentina is still a very fragile democracy,” says King. “But every time I go there, it is stronger—it has broad support.” Still, Di Lonardo’s researchers are putting themselves at risk. “If there were a military coup, they would be in terrific danger,” King notes.

Although the Grandmothers spent nearly a decade tracking down disappeared grandchildren, they haven’t insisted that every identified child be automatically returned to the natural grandparents. When the adopting families were unconnected to the military and had adopted children in good faith, the Grandmothers asked only that the children be able to visit their real relatives on a regular basis, be allowed to use their own names, and be told their true identity.

Half of the cases of identified children of the disappeared, in fact, were resolved between the families themselves. But when military officers implicated in torture and murder of the disappeared were involved, the Grandmothers insisted that the children be returned to their biological relatives, arguing that a kidnapper, if discovered many years later, would never be allowed to keep the child he abducted.

Bones Tell Their Story

The forensic part of the U.S.-Argentinian collaboration set up in June 1984 has succeeded in identifying a number of the disappeared from skeletal remains. Almost 300 skeletons have now been unearthed and are being studied by teams trained by U.S. forensic specialists. Clyde Snow is currently spending a year in Argentina working on the identification process. Each exhumation lasts eight hours, using archeological methods normally employed to study fossils.

Forensic identification of Argentinian disappeared is complicated by “the diabolical way the military eliminated people,” according to Luke Tedeschi. “They would pick up people in one town, detain them in another, torture and kill them, then take them to another locale where they were dumped in mass graves with hundreds of others and intermingled with paupers.” In addition, some bodies were partly dismembered to prevent identification.

“But bones have a story to tell,” says Tedeschi. “Time is not a factor.” The forensic teams have proven and testified in court that most of the dead died not in shootouts with police, as claimed, but from single gunshots to the head at short range, execution-style. Each identified skeleton helped make a case against military officers on trial.

For families of the disappeared, however, the forensic work took on more personal meaning. Tedeschi, an Amnesty International activist for 15 years, remembers the first public forum in Argentina at which the forensic team explained what they thought they could do.

A man named Lanuscou spoke up, asking, “Do babies’ bones disappear?” It turned out that his son, daughter-in-law, and children aged 6 years, 5 years, and 6 months were murdered in their home in 1976 and then buried in a common grave. All were recorded as killed in combat with military police. When the remains were dug up in 1984, Lanuscou found four bodies, but in the smallest box he found only a pacifier, diapers, and a teddy bear.

Dismissing his questions about the whereabouts of his youngest grandchild’s remains, the coroner told him that “babies’ bones disintegrate.” That was his question to the forensic team: do a baby’s bones disintegrate? On hearing that they do not, Lanuscou burst out crying, saying, “Then my granddaughter is still alive!”

The complicit role that Argentinian forensic specialists played during the military regime made setting up a U.S.-Argentinian forensic team difficult at first. Finding Agentinian forensic specialists to work with proved impossible, says Tedeschi. “Most forensic pathologists had been in office during the military regime and had been involved. We didn’t find any we felt comfortable with.”

During military rule, pathologists routinely forged records on cause of death. Instead, the team looked to young graduate and doctoral students in human rights groups who wanted those involved brought to trial. “A core of them wanted the world to know what happened here,” says Tedeschi. “They told one story after another of people with really little political affiliation disappearing, one after another.”

After each exhumation, the teams washed and then reconstructed each skeleton, consisting of 206 bones and 32 teeth. They would then determine height, sex, age, stature, race, and right- or left-handedness. Medical records, including x-rays and dental charts, helped to identify who the person was. Forensic techniques could pinpoint torture-related trauma and cause of death.

Again, it was the young Argentinian trainees who took the greatest risk. “The military were all around,” said Tedeschi. “We could see that the officers we talked to knew what was going on and had participated in it. You could sense if they were pushed too far, there would be big trouble.”

In the end, both genetic and forensic techniques served not only to identify the disappeared and their children, but also combined with eyewitness accounts and evidence gathered by the Madres and Abuelas to bring their torturers and murderers to justice. So far, the top nine military officers have been prosecuted. About 1,700 cases against lower-ranking officers are pending.

The military waited to kill a pregnant woman until after she gave birth—but this rule didn’t apply to torture. The newborn children were then sold on the black market, given to adoption agencies, or taken as “war booty” into military families.

Human Rights Precedent

Argentina has set a precedent in pursuing those guilty of human rights violations, asking for outside expertise, accepting in-court genetic and forensic evidence, and pursuing the torturers and murderers of the disappeared. “People who engage in torture can now be told, ‘We can prove it,'” says Tedeschi. No matter how many years pass, government agents and military officers who murder innocent civilians can be tracked down. This could cause torturers to have second thoughts in the future, knowing that they can eventually be prosecuted for inhumane actions.

The example of Argentina’s pursuit of justice has spread beyond its borders. In Guatemala, human rights groups, despite the murders of two founding members in 1985, march regularly to demand the return of their relatives’ bodies. In Chile, the country’s medical association has suspended doctors who participated in state-tolerated torture.

Even while torture and disappearances persist, and 200 complaints of torture have been filed in court, military physicians in Chile have approached the medical association to report that they had been ordered by superiors to examine or treat torture victims. These physicians have asked for the association’s support in informing the military that they would not cover up torture.

This past December, a second team of forensic scientists and students, including Clyde Snow and Argentinian students trained by him, trained a group of scientists and students in the Philippines in exhumation and skeleton-identification techniques, and in methods of determining both cause of death and evidence of torture. Currently, 619 Philippine citizens are listed as missing, most disappeared during 1984 and 1985. Reports of torture were prevalent throughout Ferdinand Marcos’s regime. The AAAS-sponsored delegation was invited by the new Philippine president, Cory Aquino, and human rights groups such as the Families of the Involuntarily Disappeared and Medical Action Group.

The movement to use science to uncover the disappeared and to track their torturers and murderers is growing. “The military has a network of collaborators all over the world,” says Mary Claire King. “We can set up networks that are just as strong.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

- NOVA, the public television science series, premiered “The Search for the Disappeared” on October 14, 1986 (check local PBS listings for repeats), which describes forensic and genetic methods used to identify Argentina’s disappeared. A transcript of the one-hour show is available for $4 from NOVA, Box 322, Boston, MA 02134. A video cassette or 16 mm. film of the show is available from Coroner Film and Video, 108 Wilmot Rd., Deerfield, IL 60015 (1-800-621-2131).

- Amnesty International. The Missing Children of Argentina: A Report on Current Investigations. Amnesty International USA, July 1985.

- “Special Report: The Medical Profession and the Prevention of Torture.” New England Journal of Medicine. October 24, 1985, 313:1102-1104.

- Simpson, John and Jana Bennett. The Disappeared and the Mothers of the Plaza: The Story of the 11,000 Argentinians Who Vanished. St. Martin Press, 1985.

- “Human Genetics and Human Rights: Identifying the Families of Kidnapped Children.” American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. December 1984, Vol. 5, No.4, pp. 339-347.

- “The Investigation of the Human Remains of the ‘Disappeared’ in Argentina.” American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. December 1984, Vol. 5, No.4, pp. 297-299.

>> Back to Vol. 19, No. 1 <<