This essay is reproduced here as it appeared in the print edition of the original Science for the People magazine. These web-formatted archives are preserved complete with typographical errors and available for reference and educational and activist use. Scanned PDFs of the back issues can be browsed by headline at the website for the 2014 SftP conference held at UMass-Amherst. For more information or to support the project, email sftp.publishing@gmail.com

How Magazines Cover Sex Difference Research: Journalism Abdicates its Watchdog Role

by Barbara Beckwith

‘Science for the People’ Vol. 16, No. 4, Month 1984, p. 18-23

Barbara Beckwith is a freelance writer, former high school teacher, and longtime member of SftP.

A debate has continued for ten years now over genetic explanations for human social behavior. The controversy first centered on sociobiological theory; more recently the focus has been on sex hormones and brain structures as explanations for social differences, especially between the sexes.

Scientific journals have covered that debate to a certain degree, although much of their coverage is skewed in favor of genetic explanations and away from positions taken by their critics. Readers of The New York Times, for example, are usually informed about these issues through the filter of science writer Boyce Rensberger, a sociobiology enthusiast.

But what about the public in general? What do nonscientists or nonacademics know of “genes-and-gender” theory and the debate about it? Over the last five years, mass circulation magazines have taken on genes-and-gender science as a favorite topic. The ongoing debate over the validity of those theories, however, has not met with the same enthusiasm. Most of the popular press announce genes-and-gender “findings” without giving their readers an inkling of the existence of critics.

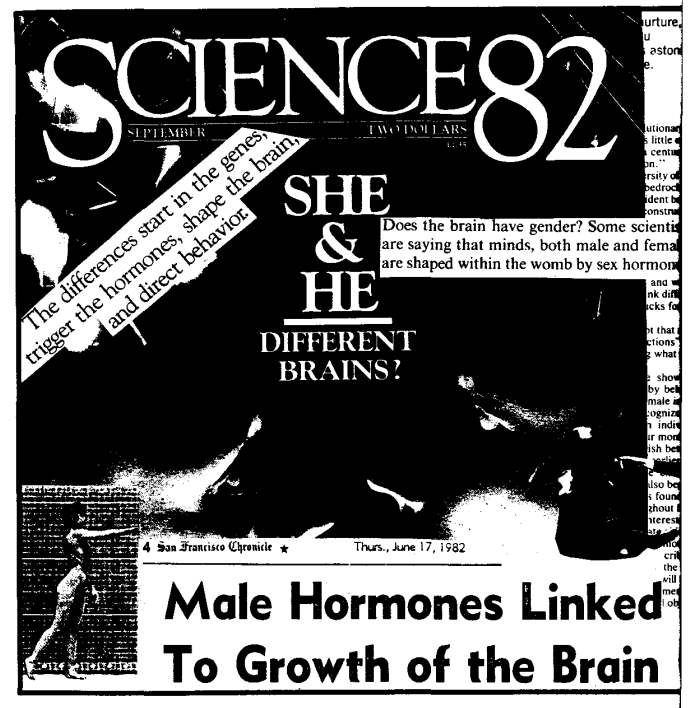

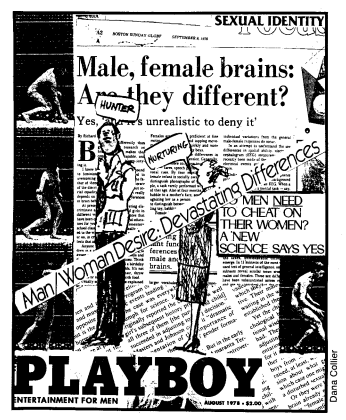

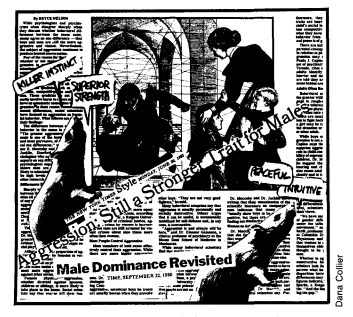

Genes-and-gender science has sold well in a whole spectrum of popular magazines. In 1981, Newsweek devoted six pages to the behavioral sex differences in an article titled “How They Differ—and Why.” Discovery ran “The Brain: His and Hers” that same year, and Science 82 followed with a “He and She” article the next year. Science Digest ran an 8-article feature in 1982, asking “Are Sexual Standards Inherited?” and answering with an enthusiastic yes. Redbook and Parents 1980 articles advised parents how to treat their sons and daughters in light of the “new research.” McCalls printed its own study of maternal “baby hunger” in 1981 and followed up in 1982 with an article on how men cope with women whose urge have babies they don’t feel or understand. Ladies Home Journal chimed in with a “fun piece” on women’s maternal instinct. Playboy spent seven months in 1982 exploring biological explanations behind sex-role differences. Cosmopolitan published four articles on the topic that same year, with titles such as “Is Anatomy Destiny?” and “Why the Sexes Still Rage at Each Other.”

Genes-and-gender articles span the full spectrum of popular magazines, from newsweeklies to science, sex, education and women’s magazines. Most fail to mention there is no consensus among scientists that such connections make logical or empirical sense. In effect, such coverage panders to conventional sex-role prejudices by telling readers “science” supports their biases. Popular magazines use genes-and-gender theories as justification for keeping things as they are. The five most popular science magazines—Science Digest, Science 84, Discover, Omni and Pyschology Today—have printed genes-and-gender articles virtually ignoring the debate going on about the issue. Those five have a combined circulation of 2.3 million. In contrast, Science for the People which has extensively critiqued gene-based social theories, has a readership of approximately 4,000.

Popular science magazines seem eager to use genes-and-gender research to justify problematic social behavoirs. In 1982-3, Science Digest ran four articles treating genetic explanations for polygamy, rape, depression in women and the sexual double standard as hard news. As recently as May, Science 84 posited as evolutionary adaptations female child battering, female infanticide and third-world nutritional neglect of women.

A One-Sided Picture

Sex magazines are equally intent upon applying genetics to sex roles. “Word has begun to leak out from the cool, impartial world of scientific inquiry,” writes Playboy in 1982, “that men and women are chemically and behaviorally as different as two sides of the same coin.” In its seven-article series, Playboy goes on to describe in detail the theories and data of 55 genes-and-gender researchers without citing a single critic. When the authors of that series were asked during a June 1983 televison debate why they had included no criticism in their presentation, they replied that this had not been their topic.

Cosmopolitan, Playboy’s popular sexual counterpart for women, published four articles in 1982 alone on biological explanations of sex-role differences. “Authorities now say nature, NOT nurture, makes him thump and thunder while you rescue lost kittens,” writes Cosmopolitian. “Intersex tyranny,” Cosmo explains to its (mostly female) readers, is caused by “instinctive and conflicting urges” between the sexes. Citing genes-and-gender theory, Cosmo concludes women should not pressure men to change—to fight less, or nurture more—since “nurturing does not come naturally. It is not instinctive but learned behavior.” Readers are advised, if their men are mean, that “snarling won’t help. He was just being male.”

Playboy and Cosmopolitan‘s combined circulation is 7.5 million. In addition, a condensation of the Playboy series, its sexual content toned down, was read by Reader’s Digest‘s 30 million readers. Clearly, a sizeable chunk of the American public is being exposed to a one-sided picture of the genes-and-gender debate.

Traditional women’s magazines are slightly more cautious, but not much. Mademoiselle’s 1981 article acknowledged scientists are divided on the validity of research showing sex differences in math skill and aggresiveness. But despite the frequent use of “might” and “could” in the body of the article, its conclusion is that of “science… coming to believe” men and women may have built-in limits and tendencies such as the tendency (in men) to roam and defend territory and responsiveness (in women) to infants. A controversial issue becomes an emergent truth, and a divided scientific community is reduced to a single entity. A lighter approach is taken by the Ladies Home Journal, in an article focusing on the maternal instinct, “the secret ‘sixth sense’ shared by all mothers.” With it, a mother can intuit when her son needs a tongue-lashing from his father and when he needs “a manly hug.” Her husband has no such innate ability.

Finding the Critics

Both of the widely-read newsweeklies, Time and Newsweek, are careful, when reporting on gene-and-gender science, to include arguments on both sides. But in a more subtle way, their coverage stacks the deck in favor of genetic explanations. Newsweek cites six critics among thirty quoted sources in a 1981 article, “The Sexes—How They Differ—and Why.” But it then calls biologically-oriented explanations “an emerging body of evidence” that “scientists now believe.” Moreover, of the critics it plays up most are “hardcore feminists” who put women researchers under “Lysenkoist pressure to hew to women’s liberation orthodoxy.” Not one of these female viragos is named or quoted; they remain anonymous foils through which critics are associated with dogmatism. In contrast, genes-and-gender researchers are clearly identified as reputable academics. University of Chicago psychologist Jerre Levy, for instance, is introduced as “a pioneer in studies of brain lateralization.”

Similarly, Science Digest uses feminist critics as comic foils. A July 1982 article introduces them with an anecedote about the bishop’s wife’s reaction to Darwin’s evolution theory: “Descended from the monkey? My dear, let us hope it isn’t true! But if it is true, let us hope it doesn’t become widely known!”

The message is clear: critics of biological explanations for sex-roles stand in the way of the advancement of science. The article goes on to quote 17 sources favoring biological explanations for human social behavior, one anonymous source against, while Harvard sociobiologist E.O. Wilson is termed a “pioneer” at the head of “the newly-kindled light of sociobiology.” Objective science is portrayed as being besieged by dogmatic militants and feminists. The very real split in the scientific community over sex-difference biology is not acknowledged.

Despite such treatment in the mainstream media, critics are not hard to find. Book-length critiques have been written or edited by Richard Lewontin, Janet Sayre, Marshall Sahlins, Lila Leibowitz, Ashley Montagu, Ruth Hubbard and Marion Lowe. They sit on the same bookshelves as genes-and-gender theorists Helen Fisher, David Barash, Sarah Blaffer-Hrdy, Daniel Freedman, Donald Symons, Richard Dawkins and Melvin Konner. Critiques by Stephen Jay Gould are as available as genes-and-gender textbooks by E.O. Wilson. A journalists need only look.

Unfortunately, once a journalistic bandwagon gets going, magazines tend to rush to get on. The result is self-fulfilling prophecy: publishers see unanimity as confirmation of the significance of the issue. In the rush, some magazines settle for reprints. A limited number of writers can spread a story among a dozen magazines. Richard Restak’s article on sex differences in the brain appeared in Education Digest, Reader’s Digest, and Newsweek. Scott Morris wrote genes-and-gender articles for Psychology Today and Playboy. Mary Batten’s 1982 Science Digest article reappeared in Cosmopolitan the next year, its sexual connotations beefed up. Not that Science Digest‘s version was asexual: while “cooler” than Playboy, it nevertheless titillated readers with suggestive titles and nude illustrations.

Justifying Male Sexual Violence

Sex, in fact, seems to be a major reason why popular magazines are eager to write about genes-and-gender research. The topic supplies readers with a rich assortment of bizzare sexual anedcotes. Playboy regales its (mostly male) readers with accounts of sixty-pound elephant penises, chimp testicles which product “huge amounts of sperm” and red deer stags’ “sneaky-fucker strategy.” Connections to humans are accomplished through simple athropomorphic imagery. Playboy talks of a male fly that “tries it” with a raisin and a boot; Cosmopolitan describes plants that “get attention by exposing themselves—at least one male fly has been caught ejaculating on a blossom.”

Both Playboy and Cosmopolitan promote more than sex; they provide biological justification for strict sex-roles and sexual violence. A February 1981 Playboy concludes males are “compelled by their gender to be rogues” and advises men: “If you get caught fooling around, don’t say the Devil made you do it. It’s the Devil in your DNA.” In April 1981, Playboy suggests rape is very likely “a strategy genetically available to low-dominance males that increase their chances of reproducing by making more females available to them than they would otherwise.” The February 1981 Psychology Today makes the same suggestion. Genetic explanations for rape were fully critiqued by Val Dusek in the January/February 1984 Science for the People. But 960,000 more people will hear Pyschology Today‘s interpretation.

Even more alarming is Cosmopolitan‘s eagerness to justify male sexual violence. A May 1982 article promises to “provide a new perspective on human rape, wife-beating and other forms of sexual aggression.” Cosmopolitan then describes an assortment of nonhuman “sexual tricksters,” “mating game conflicts” and ‘death by sex.” The article concludes with advice to its (female) readers to take “guilt-ridden nightmares from the closet, sweep out tangled webs of Freudian fantasies, and simply have fun.” The astonishing message: rape and wife-beating are dismissable as gene-based and fun.

Magazines whose readership is not sex-oriented focuses on sex-roles instead of sex. A 1980 Commentary article uses genes-and-gender research as proof that affirmative action quotas and textbook “indoctrination into sexual equality” should be stopped. A 198 Education Digest article, citing brain research, proposes setting up different learning sequences for boys and girls “to allow for their separate predispositions.” Clearly, genes-and-gender research is popular in part becuase it justifies traditional sex differences. Another part of the explanation lies in how journalists view science in general.

Science Journalists: Not Critically Oriented

According to Rae Goodell, associate professor of science writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the press tends to take “an upbeat, ‘science saves’ view of science.” “Journalists react with awe, excitement or resentment toward scientists, but all too rarely with common sense,” writes Goodell in a November /December 1980 Columbia Journalism Review article.” Since science journalism programs have generally not been critically oriented, according to Goodell, science journalists have allowed themselves to be intimidated by high-status scientists. “Most science journalism education has a trade orientation that views science news as value-free, apolitical hard news.” Such an education doesn’t prepare journalists to look for more than one side to a science story.

Ohio University journalism proffessor Sharon Dunwoody points out that science writers tend to work in “inner-circles,” sharing story ideas, sources and background information. As a result, they often publish the same news instead of making independent judgements about what is worth printing, writes Dunwoody in a 1980 Science, Technology and Human Values article.

Scientists, too, work in “inner-circles.” “There is a tendency for a department to perpetuate the kind of research it is already doing,” says Harvard biologist Ruth Hubbard. “There’s a heavy self-selection toward people who think the same way.” Departments hire researchers who hold compatible views. Journalists who don’t go beyond a researcher’s department to ask questions might never find out the researcher’s work is under debate.

When scientists and journalists become too-comfortable allies, the public may lose out. If readers can’t shop at the full “marketplace of ideas,” they won’t have a chance to sort through contradictory reports from competing sources and decide for themselves what to think.

Science appears in the press largely as a subject for consumption rather than critical scrutiny, according to science writer Dorothy Nelkin in a May 14, Boston Globe article on science and the media. Political questions of scientific responsibility and ideological priorities that guide scientific choice are seldom considered news,” writes Nelkin. As a result, “the public’s need to know about science—it’s problems as well as its promises—is often poorly served.”

“Scientists, and the data we produce, are not and cannot be free from the prejudices, ideologies, or interests of the larger society,” writes Karen Messing, University of Montreal genetics professor. Her article in the book Women’s Nature: Rationalizations of Inequality points out each step in the scientific process where bias, particularly sex and class bias, enters in. First, bias is found in the selection of scientists and their access to space, equipment, grant money and “old-boy networking.” Next, the choice of a research topic is influenced by the researcher, the researcher’s employer, and the grant provider. Then, the way the research hypothesis is posed and carried out, especially the choice of study population, controls, method of observation and data analysis all areas where biases are exhibited. Finally, the publication and popularization of results depends upon the researcher’s status, how results fit accepted dogma, and the researcher’s desire to influence public opinion.

Few scientists or journalists take Messing’s view of science as influenced by sex and class. For example, Harvard University sociobiologist E.O. Wilson insists his work is value-free and apolitical. “My interest has been to keep my personal political biases from influencing my conclusions about human nature. In the past few years, I’ve allowed my beliefs to float free in order to be as fully objective as possible,” says Wilson in a Boston Magazine interview. But numerous analyses of Wilson’s writings point out how bias has affected his choice of data and conclusions.

In contrast, Northeastern University anthropologist Lila Leibowitz is frank about the lens she sees through. “I have a preconception about human beings as socially adaptive products of plasticity,” Leibowitz explained in a recent interview. Harvard University biologist Ruth Hubbard is similarly aware of her own frame of reference and how it differs from genes-and-gender scientists. “There are people who are for whatever reasons of their own past history of living in this world, want to believe the world is the way it is because that’s the way it has to be,” said Hubbard in an interview. “They tempermentally prefer a deterministic mold. Others like to think there are a lot of options, that things happen to be the way they are for very particular reasons that you can understand and alter. That certainly is my picture.”

Most science journalists view science as neutral, and report scientific research as straight news. By doing so, they deprive the public of the marketplace of ideas they are entitled to. By filtering the controversy about genes-and-gender research so that only one side gets through, popular magazine writers serve to shore up the status quo. In this way, mass circulation magazine coverage of genes-and-gender theory affects public policy. The notion of the “different natures” of men and women is profoundly conservative, and can influence public policy on affirmative action, day care, the sexaul double standard and parity in employment and political power. Genes-and-gender theories also reinforce tradtional attitudes toward rape and other forms of sexual violence. In the end, the self-serving zeal with which popular magazines have embraced genes-and-gender science can have diastrous effects on women.

An Historical ParallelA striking parallel with the current popularization of genes-and-gender science is found in the early part of this century when popular magazines promoted the theories of the newly founded “science” of eugenics. Led by Popular Science Monthly edited by James McKeen Cattell (a major figure in the mental testing movement), these magazines inundated the public with articles describing the latests “findings” on the genetic basis of criminality, racial differences in intelligence and the genetic inferiority of many immigrants. For instance, a series of articles was published in the years 1913-1915 in Cattell’s journals with the titles “Going through Ellis Island,” “A Study of Jewish Psychopathy,” “Mendelian Inheritance of Feeblemindedness,” “The Biological Status and Social Worth of the Mullato,” “Heredity, Culpability, Praiseworthiness and Reward,” “Eugenics with Special Reference to Intellect and Character,” “Immigration and the Public Health,” “A Problem in Educational Eugenics,” “Women in Industry,” “Economic Factors in Eugenics,” “The Racial Element in National Vitality,” “Eugenics and War” and “Families of American Men of Science.” All promoted the ideas that social behavior and aptitudes were genetically determined. These popular articles included ones written by leaders of the eugenics and mental testing movements, such as E.C. Thorndike, C.B. Davenport and Cattell himself. Similarly, Atlantic Magazine in 1914 published “The Decadence of Human Heredity” suggesting reduced “multiplication of the defective classes” and increased fecundity of Harvard and Yale graduates. The January 1914 issue of Outlook featured an article by Theodore Roosevelt, “Twisted Eugenics,” which urged sterilization of eugenics to prevent the “race” from dying out. The Saturday Evening Post was also a great fan of the eugenicists, including articles such as “The Great American Myth” and “Plain Remarks on Immigration from Plan Americans” (in 1924) which called on Americans to “breed the black sheep out of our flocks.” Other popular magazines, newspapers and the respected Scientific American also presented the views of the eugenicists uncritically. The result of this barrage of uncontested eugenics propaganda in the popular media was to provide strong popular support for the sterilization laws, miscegenation laws and for the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924 which tremendously reduced the influx of immigrants from the supposedly “inferior” nations. Let us hope that the current wave of enthusiasm for biological determinist theories among the contemporary couterpart of the magazines of the early 1900’s does not lead to similarly strong consequences. – Jon Beckwith |

POPULAR MAGAZINE ARTICLES ON BIOLOGY AND SEX ROLES

Except for those published in Ms., most of these articles present uncritically the views of those scientists who propose that gender behavior is biologically programmed.

Commentary: “The Feminist Mystique” by Michael Lewin, 12/80.

Cosmopolitan: “Is Anatomy Destiny?” by Tim Hackler, 3/82.

“The Brain: Something to Think About” by Jonathan Tucker, 5/82.

“Why the Sexes Still Rage at Each Other” by Jane Clapperton, 5/82.

“How to Have Sex If You’re Not Human” by Mary Batten, 5/82.

Discover: “The Brain: His and Hers” by Pamela Weintraub, 4/81.

Education Digest: “Brain Behavioral Differences” by Richard M. Restak, 4/80.

“Do Boys and Girls Need Different Schooling?” by Carlotta Miles, 4/81.

Ladies Home Journal: “Only a Mother Would Know…” by Shirley Lueth, 5/81.

Mademoiselle: “Men vs. Women: What Difference Do the Differences Really Make?” by Annie Gottlieb, 7/81.

McCalls: “How Different Are Girls and Boys?” by Dr. Lee Salk, 9/79.

“Baby Hunger” by Lois Leiderman Davitz, 11/81.

“How Men Really Feel About Babies” by Lois Leiderman Davitz, 6/82.

Ms.: “The ‘Math’ Gene and Other Symptoms of the Biology Backlash” by Nancy Tooney, 9/81.

“Watch Out: Your Brain May Be Used Against You” by Vivian Gornick, 5/82.

“Tired of Arguing About ‘Natural Inferiority’?” by Naomi Weisstein, 11/82.

Newsweek: “Just How the Sexes Differ,” 5/18/81.

Omni: “Sex and the Split Brain,” 8/83.

“Animal Feminism” by C. Johmann, 8/83.

Parents: “The Truth About Sex Differences” by Susan Meunchow, 2/80.

Playboy: “Darwin and the Double Standard” by Scott Morris, 8/78.

“Why Do Men Rape?” by Richard Rhodes, 4/81.

“The Sexes: A Mystery Solved?” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 1/82.

“The Sexual Deal: A Story of Civilization” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 2/82.

“The Sex Life of the Brain” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 3/82.

“The Sex Chemicals” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 4/82.

“The Perils of Paul, the Pangs of Pauline” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 5/82.

“The Main Event” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 6/82.

“Prisoners of Culture” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 7/82.

Psychology Today: “Sexual Selection in Birdland” by D.P. Barash, 3/78.

“Eros and Alley Oop,” David Symons interviewed by Sam Keen, 2/81.

Quest: “Male and Female—Why?” by Jo Durden-Smith, 10/80.

Reader’s Digest: “The Other Difference Between Boys and Girls” by Richard Restak, 11/79.

“Is There a Superior Sex?” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 11/82.

Redbook: “Should We Treat Our Son and Daughter Just Alike?” by T. Berry Brazelton, 8/80.

Science 82: “He and She” by Melvin Konner, 9/82.

“Symons Says” by Roger Bingham, 1-2/83.

“Margaret Mead: The Nature-Nurture Debate and On Being Human” by Boyce Rensberger, 4/83.

Science Digest: “Sexual Choices” by Mary Batten, 3/82.

“Sociobiology: Rethinking Human Nature” by Richard Nalley with contributing articles by Mary Batten, Nancy Solomon, E.O. Wilson, Rachel Wilder, 7/82.

“Sex Machines” by Duncan Anderson, 4/82.

“Birth of Your Sexual Identity” by Jo Durden-Smith and Diane de Simone, 9/83.

Time: “Why You Do What You Do: Sociobiology, A New Theory of Behavior,” 8/1/77.

“Male Dominance Revisited” by John Leo, 9/22/80.